In September 1967, 20-year-old David Bowie found himself in suspension. His self-titled debut album released a couple of months prior had been a flop. An artistic hero, Syd Barrett, had delivered a part ambivalent, part mocking, but nonetheless encouraging boost for his ‘Love You Till Tuesday’ single via a review in Melody Maker. But that too had flopped. His record label had just rejected a follow-up single, ‘Let Me Sleep Beside You’. He spent a couple of days that month being playing a painting by a schizophrenic artist that comes to life in a short, X-rated horror film called The Image; it was screened briefly two years later in an adult cinema between porn films. The future was, if anything, murky.

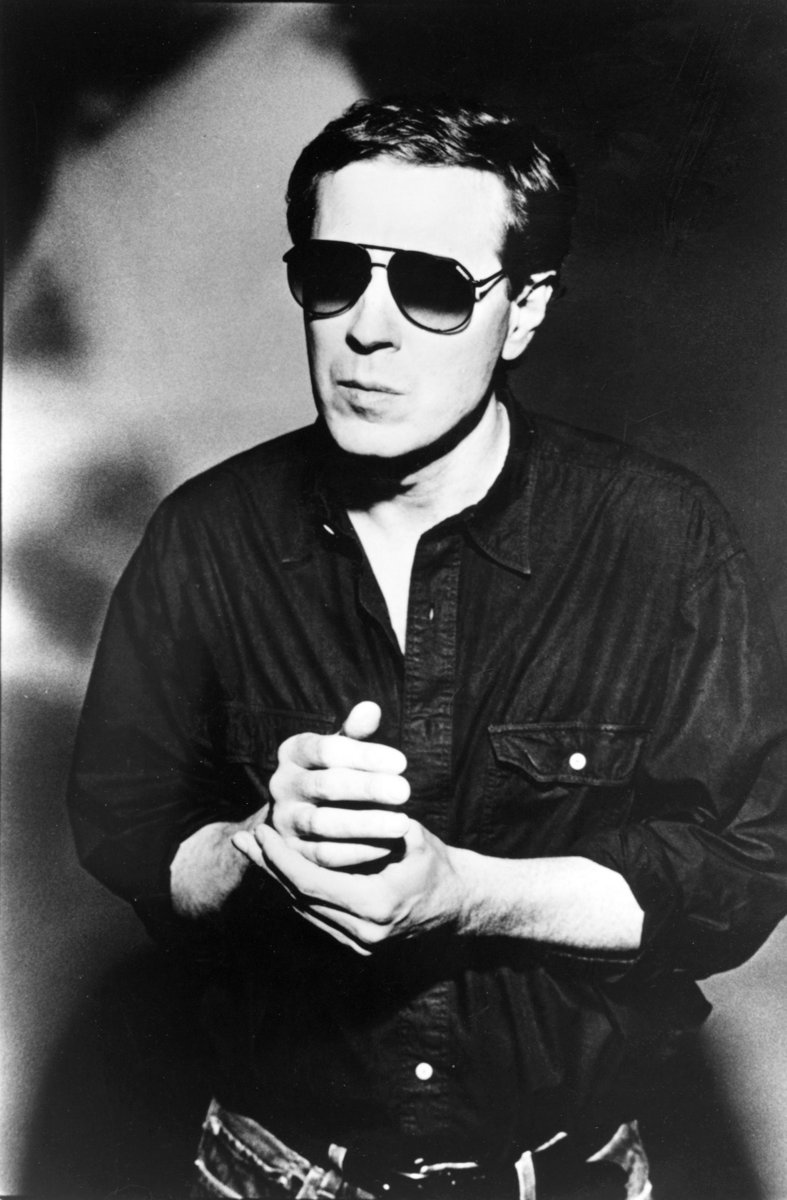

In September 1967, 24-year-old Scott Walker found himself feeling lighter than air. Having moved to the UK two years prior as one of the Walker Brothers, he’d scored smash hits with the group and stretched his creative wings increasingly as a result. His frustrations with the band setup and expectations weighed on him enough to lead to the Walker Brothers breakup earlier that summer, but his solo debut Scott appeared that month, rising to number 3 on the UK charts. The future seemed reasonably assured, at least for the moment.

Many years later, in a documentary, Scott Walker: 30 Century Man, Bowie would tell a story about how he dated an ex-girlfriend of Walker’s somewhere around this time. She apparently loved Walker’s music more and would play it constantly.

There’s a famed clip from Mary Ann Hobbs’ BBC radio show around the time of David Bowie‘s 50th birthday events in 1997 where, among other figures, Scott Walker left a message for him of deep praise. For what seems like the only time, the genial, winning front Bowie had developed for dealing with interviewers slipped just a touch. There was a crack in the facade: a breath, a pause, “Wow. That’s amazing. I see God in the window.” It’s the closest anyone would ever get to a dialogue on record between the two, and perhaps appropriately, it was mediated, in public and yet at a remove. Such was the interplay, such was the myth-making.

It is long past time to reconsider the reductive image of the solo artistic genius, especially the white dude ones, the ones who are presented as functioning on their own when they never in fact did. Bowie and Walker were nexus points, not sui generis; burning with ambition and a desire for knowledge, they cast nets widely with the help of others, the literature and artists and movies and more that they referenced, the producers and engineers and musicians who worked with them. One figure ended up growing and maintaining that wide network across decades in public, a subject of curiosity even when out of the public eye for years; the other kept a much closer circle but one no less dedicated, and who eventually was noticed only when he chose to be noticed. But it boiled down to them in the end. Even without ever working together – indeed, perhaps never being in the same room, much less the same building, though definitely pounding the same city streets during the same time – they truly did seem, to borrow Chris O’Leary’s excellent metaphor from his initial Bowiesongs blog entry on the two men, “two planets in the same system.”

The blog entry quoted above was for Walker’s 1978 composition ‘Nite Flights’, the song that captured another, if slightly broader, moment in time involving both musicians. The effects of this song are arguably still playing out today, if still nowhere near the mainstream musical zeitgeist. When Walker was interviewed for Melody Maker in February 1976 because of the recent Walker Brothers reunion, September 1967 must have seemed a long way away. After a supernova of a late 1960s solo career, he’d spent much of the Seventies releasing albums of desultory covers, hovering at a Jack Jones-level of artistic ambition, and not even hitting those heights in terms of fame. In contrast Bowie had spent the decade not only becoming a star at home but had done something Walker never had, breaking America big with Young Americans and ‘Fame’. After expressing his frustration to the interviewer about record labels still pressing him for more of the same – things he felt he’d already done – Walker, unprompted, put his cards on the table by adding: “David Bowie, he’s a very smart guy. He comes up with the goods and he makes sure of delivery right down the line. I thought, ‘Shit, if he can do it, so can I.'”

Exactly two years later, Walker switched from words to action. By that point, Bowie had released three further albums, scoring more hits and critical kudos along the way, shifting from LA to Berlin, while still finding time to produce Iggy Pop and tour as his sideman. And during all of that, following a large UK hit with a cover of Tom Rush’s ‘No Regrets’, the rest of the reunited Walker Brothers efforts went nowhere. There was one last guaranteed album release for the group on the cards, so he spent 1977 focusing on writing new songs, with Bowie (and Joni Mitchell) acting as a source of inspiration. Walker entered the sessions in February 1978 to record what would become Nite Flights. Engineer Steve Parker said that Walker brought Bowie’s most recent album, “Heroes” for use as ‘reference’. Nite Flights had experimentation, unexpected shifts, transformative mixing and performances, the surging brilliance of the title track, and of course a voice that had its parallels and similarities with a mode that Bowie himself had overtly leaned into more than once. Walker knew what he was doing when he arrived in the studio with that LP.

And Bowie was far from unaware of the results, with Brian Eno bringing a copy of Nite Flights to the sessions that would result in Lodger. Walker’s songs were the first four on the album, a stacking of the deck that cast everything that followed in its shadow. Two of Scott’s tracks in particular digged in deep. The title track was somewhere between Bowie’s sweep of command and Bryan Ferry‘s jet-set/smart-set dreams, shimmering into the heavens with dark disco propulsion. Walker intoned lines like, “The stitches torn and broke/the raw meat fist you choke” and “Broken necks, featherweights press the walls.” But even this was as nothing compared to ‘The Electrician’. These ominous notes acted as introductory markers of time. There was dread in the corners and shadows of this mix and arrangement, only partially leavened by a burst of relief mid-song, accentuated by a soft flourish of flamenco guitar from famed session man Big Jim Sullivan. Walker sung of the work of a torturer, in the decade of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet’s obscene triumph and Victor Jara’s brutal death, but referencing so much more: “If I jerk the handle, you’ll die in your dreams” and “When lights go low/ There’s no help, no”. Conventional song structure was starting to slip away in turn, a subtle but notable shift.

Bowie was apparently moved by what he heard, his responses staggered into view over time in turn and a Lodger track was given the familiar sounding name ‘African Night Flight’. Bowie’s singing throughout the album often had the bravura edge of Walker at his most dramatic. But with Scary Monsters, Bowie entered a different phase of noting his disciples more than his contemporaries, and then recalibrating more towards calculated chart success and rode out the eighties eventually becoming even more famous for being famous. Walker, however, seemingly went to ground, surfacing only with 1984’s Climate Of Hunter. The retrospective bemusement at Mark Knopfler and Billy Ocean’s presence on this record was far less notable at the time and the album marked the beginning of Walker’s partnership with young engineer Peter Walsh, a connection that would last for the rest of Walker’s life. There was also the increasing evidence of intentionally fractured compositional and recording approaches, the sense of sound as element to be deployed as desired, a lyrical perspective that was vivid in details but cryptic at best in easy summary. Another connection might have been even closer all around had two producers who volunteered their services for Climate Of Hunter been chosen: Bowie and Eno. (Walker declined both, while later abortive sessions with the Eno/Daniel Lanois partnership led to music that was so much not to Scott Walker’s taste that, legend has it, he threw the entire set of tapes into the Thames.)

By 1993, happily finished with both his initial RCA-era reissue program and the Tin Machine exercise, Bowie breezed through a cover of ‘Nite Flights’ during his Black Tie White Noise days, perhaps feeling secure in it its self-reflexiveness as a choice, maybe figuring the apparently missing-in-action Walker needed a little royalty money. Bowie reconnected with Eno after another 1993 deck-clearing effort from the former, the Berlin-era nodding soundtrack to The Buddha Of Suburbia. They spent much of 1994 into early 1995 first creating a huge passel of improvisational efforts with backing from many familiar names in Bowie’s musical orbit. Early ideas of a set of interconnected characters were slowly reshaped into a wider story that would become Outside: a futuristic concept album, not Bowie’s first, but glistened up for a post-Cold War stretch where ‘art crime’ could be seen as both deeply important and kinda sexy. Walker and his Nite Flights work hung like a subtle but present ghost over the entire process per comments from those involved, in terms of testing boundaries, undercutting established persona and means of connection.

Easy enough to do when Walker wasn’t out there in the sense of being ‘out there’ in the public eye, as opposed to ‘out there’ in the undefined beyond. Funny thing, though: Walker was hiding in plain sight the whole time. In 1991, working again with Walsh, the American assembled a new quartet ensemble of players – a rock-band-with-keyboards lineup in appearance, but not intent, with the most important perhaps being keys player Brian Gascoigne, who would also serve as string arranger and organist. Various other guests would play everything from cimbalom to concertina, and during 1991 and 1992, songs and performances took shape. By the time Bowie was finished recording, happily concentrating on final details and planning ahead for a tour around the release which would be his first album for a new deal with Virgin Records, Walker’s own once home of Phillips was unexpectedly revealed to be his future one when its subsidiary Fontana announced a new album in turn – one due for release a few months before Bowie’s.

It had been some time since I had listened to Outside or Tilt; I hadn’t gone back to the former in full since its release and the latter I only heard after the fact. It wasn’t released in America until nearly two and a half years after the UK, and then on indie rock stalwart Drag City. Given I was born in 1971, Bowie I knew about in an ambient sense by the end of that decade, though it was only the explosive success of Let’s Dance that fully caused his name to register. In comparison Walker was an unnamed and unknown mystery, utterly off any major cultural radar in his country of birth; I only first gathered details in 1991 thanks to things like Chris Connelly’s cover of ‘The Amorous Humphrey Plugg’ and Marc Almond‘s take on Walker’s version of Jacques Brel’s ‘Jackie’. An actual encounter with his material came later still with compilations of his late 60s work some years later. Going back to both albums now after so much time, is instructive given so much has happened in the meantime; it is an odd experience, but a welcome one, a viewpoint into an era that didn’t know its future.

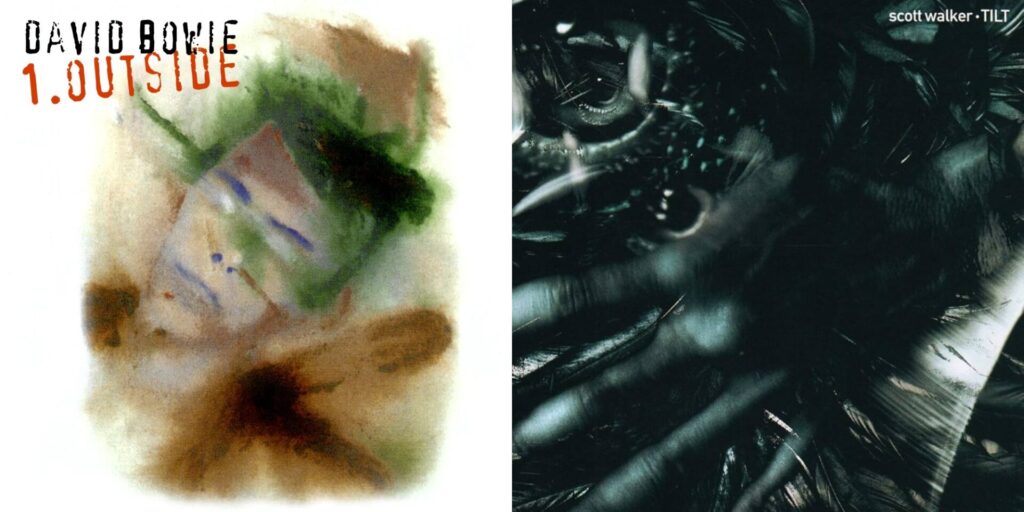

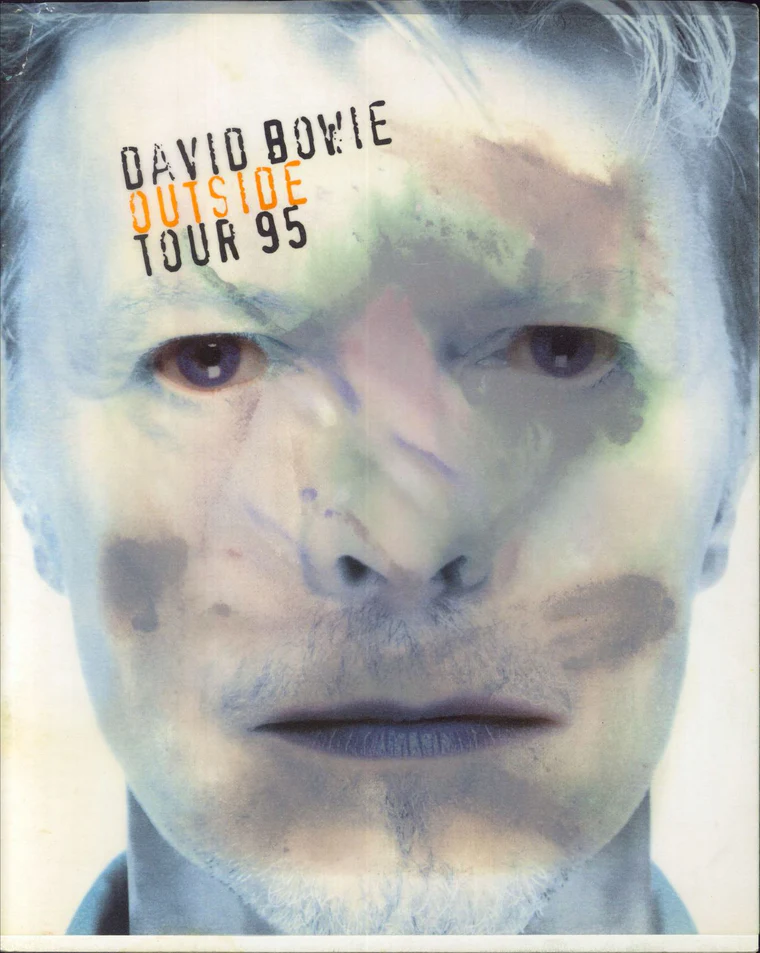

Outside – or 1. Outside as it was initially formatted nodding to the initial promise of it being the starting point of a cycle that never materialised – as far as I could remember, was somewhat meandering. It felt like a series of experiments wanting to replicate Berlin trilogy vibes but which had been either too overt in declared ambition or too overstuffed as an effort. It’s pretty much the readymade example of a CD bloat-era release, and is Bowie’s longest studio release; the equivalent of a double LP. Reencountering it doesn’t remove this sense, but severed from the context of time and place it feels more the standalone effort it became, a solitary vision bolstered by Bowie’s bloody-minded tour approach in support, adhering to his previous 1990-era claim that he wasn’t going to revisit the big hits live, moving towards an era of set lists made up of new material, plus obscurer singles and deep cuts. Outside now comes off as a gleeful, unsettled and very odd; a piece that is more than curio, while less than monumental. It’s definitely the work of an artist that sure would like your attention but wants to make you feel like you’re working for it – or at least, make you think you’re working for it.

It carries a strong air of the ‘mid-90s’ around it still. And that’s not just in the early Photoshop font/art design evident throughout the artwork contained in the CD booklet, which was planned out by Bowie to explain the album concept via a heft of visual exegesis. More than one song – lead single ‘The Hearts Filthy Lesson’, the careening pronouncements of ‘Hallo Spaceboy’ – makes it clear that if Walker remained in Bowie’s head in general terms, the Englishman’s soon to be opening act/future single collaborator Trent Reznor had recently taken up some space in turn. (I’m not complaining: the two songs that have sat with me the most over time are ‘Hallo Spaceboy’ and the nervous kick of ‘We Prick You’.) There are further hints of what could be termed adult album alternative. At many points it delivers what Rolling Stone or Q might have deemed the acceptable face of mood music; there are the crafted hip hop-friendly breaks newly-minted Portishead fans were glomming onto; the murky trip hop evident on albums like Achtung Baby, Songs Of Faith And Devotion and Shag Tobacco by Gavin Friday. If it weren’t for the occasional lyrical nods and, more notably, the ‘segues’ in which Bowie takes on various characters from the album’s mythos – including clear demonstration he had no intention of letting go of the arch cockney character, no matter how long he’d been away from London – the whole concept idea might as well be evanescent.

Then there’s ‘The Motel’, which is as close to ‘The Electrician’ as Bowie got, or at least allowed himself to get. The sense of it, musically, is less cousin, more buffed afterglow, something that allows oneself a distance: watching an implied horror perhaps but not trapped in the room with the destructor. (Think of Se7en, the film from that year that included ‘The Hearts Filthy Lesson’ playing over the end credits. You may know what’s in the box, but do you really want to look?) The lyrics might describe a younger version of the dysfunctional abusive figures in Lodger‘s ‘Repetition’, people who are “living from hour to hour down here”, but whatever terrors underscore things are sublimated, not even hinted at allusively beyond the concluding lines about how “me exploding you” has ceased. Mike Garson, returning as Bowie collaborator after a couple of decades, adds piano flourishes here (and throughout the album) giving the listener something to hold on to: a bit of delight, or perhaps some whimsy. The guitar noise towards the end of the track snarls a bit but doesn’t crush, drums steadily drive but don’t maintain relentless inevitability, there is unease but there is no terror at all. “Lights go low,” Walker had sung. Here, “it’s lights up, boys.”

In contrast, the lights were arguably out all over Tilt, an album of ghosts, emptiness and terrifying remove. If anyone was living in Walker’s head at this point, it was, simply, the dead, the victims, their killers, the crush of history’s flow, the long-established form of lieder, art song as mournful invocation by an aging male siren. In a strange way, Walker and Bowie had another parallel moment; this was Walker’s own longest studio release to this point, nine songs and just short of an hour. Yet where Bowie was happy being a liminal figure still between the mainstream and something else – touching on the fringes of the avant-garde, with plenty of songs that allowed themselves familiar enough structures – Walker paid no concern in the slightest to such considerations. From the opening of ‘Farmer In The City (Remembering Pasolini)’, Walker singing, “Do I hear twenty-one/ Twenty-one/ Twenty-one” over the most empty sounding moments of ambient sound imaginable like a forlorn auctioneer; Tilt exists solely to be approached, not to approach.

It would be simplistic to say that Tilt is the triumph of the titular character of ‘The Electrician’, but it is the triumph of disaster. It is the triumph of trying to find out what might be left after a disaster and to communicate it as much as that is even possible, even while acknowledging you were unable to stop it from occurring, that it is already manifest. But rather than using collapsed idiom, as if from Russell Hoban‘s Riddley Walker, the words reproduced in the liner notes are clear enough; it’s the combination and flow that trips up any attempt at easy comprehension. Walker’s voice is changed from the rich flow of his younger years to a slightly higher resonance. Lyrically he sometimes appears to welcome immediate understanding, but even then requires concentration as any number of cultural and historical reference points are taken as a given without need of much elaboration. The liner notes may tell you that both the trials of Queen Charlotte and Adolf Eichmann are quoted in ‘The Cockfighters’; but how quickly can you catch the shifts between these allusions; that this is a rejection of attempts to isolate fascism in a finality and instead an acknowledgment of it as a continuing presence.

If there’s musical tension between the work of the core ensemble and various guests, it isn’t evident; the songs can shift volume and intensity in a moment, but everything sounds of a piece, like it all emerged as such rather than – as it was in reality – carefully honed to a precise series of points. It arguably gets more accessible the more the album goes on. ‘Bolivia ‘95’ starts with a gentle groove that makes its shards of forthcoming allusions, hovering around the images of American economic and cultural imperialism in one of the countries it likes to think it needs an overriding interest in, easier to move with. The concluding ‘Rosary’ completely upends all expectations simply by featuring Walker on vocals and guitar, nothing else. But the more telling points are Gascoigne’s string arrangements, haunted and terrifyingly elegant, his organ blasts on songs like ‘Manhattan’, the nervous “locust sounds” provided by Nigel Eaton’s hurdy gurdy on ‘Bouncer See Bouncer…’, the hints and flecks of sound on ‘Patriot (A Single)’. And perhaps this is Walker’s own sonic response to ‘The Electrician’. The song is suddenly sweeping at points even when arms deals, militarism and war reveal its true course, as much as it can ever be clearly observed and understood.

Most of what remained of Walker’s fans couldn’t deal with it. Or they couldn’t deal with it at first, anyhow. To say Tilt‘s sales were minimal was to understate the commercial calamity. I recall reading comments here and there, some retrospective, from figures like Almond, like Friday, that whole generation of late 70s-into-early 80s UK performers in particular who had found their own way to both Bowie and Walker in the past but found that it was Walker as he existed, firmly in the past, that probably suited them best. They really weren’t sure what to make of what had just happened. The contemporary groups and performers in turn that turned to Walker as a kind of avatar to admire as an alternative while the stereotypes of Britpop blossomed were similarly interested primarily in his elegantly sad and conventionally orchestrated anthems about love. Perhaps only Pulp bridged both eras. They took a different and more appreciative (if still more retrospective) tack in subsequent years when ‘Nite Flights’ became a clear touchstone for the dark pulse and moan of ‘Party Hard’.

Over time a more positive view of Tilt would emerge, its shock of the new turned into an outsider beacon. There was one vocal supporter then and there, though, in interviews and comments during the rest of 1995. “Adventurous,” “brave,” “true” to Walker, who “works without compromising” – Bowie had been slightly pipped to the release punch but also knew that even if Outside wasn’t going to be another Young Americans, Let’s Dance, even a “Heroes”, it was going to be far more immediate and better known than Tilt. Better to be magnanimous in admiration than have to fret over a possible conflict that was never going to exist to begin with. Soon enough, the vague plans for a followup album with Eno called Contamination would recede into the realm of never-was-going-to-happen, Bowie would notice drum & bass and Alexander McQueen in equal measure, find new angles and find ways back into his past as well. Walker would plan for whatever he hoped to do next, keeping his own counsel. Time would yet tell what the future was.

In January 2026, it will be ten years since the death of David Bowie, announced a couple of days after the release of what proved to be his last formal studio album, the unsettling jazz rock statement of Blackstar. Numerous other musicians of note would end up passing in a harrowing twelve-month period, ranging from Lemmy Kilminster to Prince to Maurice White to Merle Haggard to George Michael. But in a still popular meme that has circulated for years, it has been argued that with Bowie’s death in particular everything went to hell – next was Brexit, Trump, COVID, resurgent fascism. The meme will likely crop up again on the anniversary.

In late December 2024, the first wide release of the Brady Corbet film The Brutalist occurred in the director’s country of birth, the United States. Corbet, now regularly resident in Europe with his family, created a film that won numerous accolades and attention, with its varied themes including fascism’s impact on the personal and political level, questions of mental instability and insanity, the overbearing power of capital and sociopolitical might, the balance of artistic independence and the system needed to support it and its creators, assault and domination, the seeming impossibility of escape to anywhere that can be a true safe haven.

The film was dedicated to the some-years-deceased artist who had provided scores to Corbet’s previous two films in the 2010s: Scott Walker.