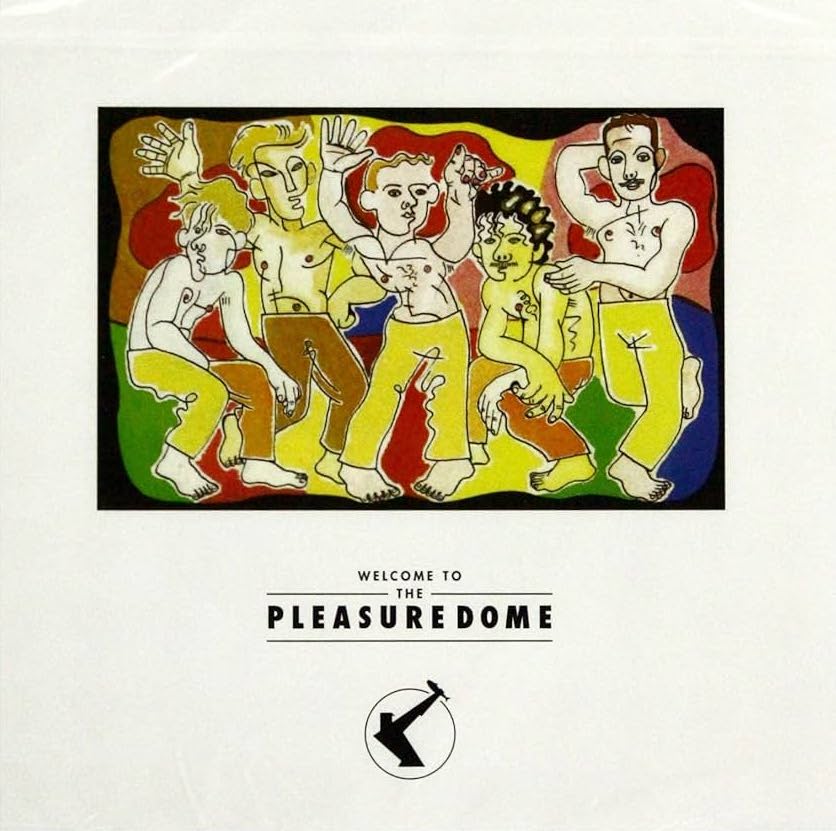

Contrary to the claims of purists, tribalists and obscurantists, the power of popular music lies in its recurring cycle of rupture, incorporation and regeneration. Bursting into 1984, lighting it up like a shooting star, then fading like a meteor’s tail, Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s brief, brilliant career was a perfectly executed enactment of pop’s push-and-pull between art and product, radicalism and corporatism, transcendence and expedience. An act designed to have the term ‘meta’ appended, Frankie took gleeful possession of the nexus of music and marketing, of queer subculture and mainstream culture, and drew power from these polarities. If Welcome To The Pleasuredome couldn’t be more of a mid-80s artefact, it also couldn’t be more relevant to the present. It’s achieved a contradictory corporate transcendence.

The late-70s Disco Sucks movement was an attempt to contain queer incursion on culture, shutting down the careers not just of Village People but of Gloria Gaynor and Chic (the backlash against Black culture is a separate story). Yet by 1984, as Ian Wade attests, the charts couldn’t have been much queerer, repression prompting regeneration again. This was the year of Culture Club’s fey frivolity ‘It’s A Miracle’, Pet Shop Boys’ archly aloof ‘West End Girls’, Weather Girls’ camply libidinal ‘It’s Raining Men’, Queen’s anthemically liberatory ‘I Want To Break Free’ and Bronski Beat’s scream of protest, ‘Smalltown Boy’. With Hi-NRG being disco in cheap disguise, Hazell Dean’s tack-fest ‘Searchin’ (I Gotta Find a Man)’, drag grotesque Divine’s ‘You Think You’re A Man’ and Dead Or Alive’s grinding ‘You Spin Me Round (Like a Record)’ absolutely chewed up the charts. Add The Smiths’ wistful ‘William, It Was Really Nothing’, Wham!’s joyful ‘Freedom’ and Madonna’s lustful ‘Like A Virgin’ and 1984 was the queerest year on record – and that’s before we even get to Frankie’s brace of (im)pure disco hits ‘Relax’ and ‘Two Tribes’. In an even bigger boo-sucks to Disco Sucks, all pop culture had come over queer in the 80s, from Prince’s lingerie fetish to Duran Duran’s ‘Rio’ video flesh-fest, and from Tom Cruise dancing in his pants in 1983’s Risky Business, to Kevin Bacon dancing in a vest in 1984’s Footloose. As Bonnie Tyler’s soundtrack hit ‘Holding Out for A Hero’ had it: a man’s “gotta to be strong and he’s gotta to be fast/And he’s gotta be fresh from the fight”. In a world of all-dancing, all-moisturising bad-boys, Tyler could as easily be describing Frankie’s Paul Rutherford as Kevin Bacon.

The relationship between repression and regeneration is a complex dance, however, and hindsight has somewhat queerwashed the decade. Hard as it is to persuade anyone of this, Freddie Mercury and George Michael were officially straight in the 80s – witness the videos for Queen’s 1980 ‘Crazy Little Thing Called Love’ (despite its leatherboy nudges) and Wham!’s 1984 ‘Last Christmas’. And no, George having come as Princess Diana to the ski-lodge doesn’t cut it when local hard-nuts had the same bleached wedge-cut and came armed with legwarmers and espadrilles. To queer matters further, Pete Burns and Elton John were married to women, and Morrissey and Boy George claimed to be asexual – with Neil Tennant’s ‘privacy’ and Divine’s pantomime dame shtick variants on this theme. Moreover, Madonna, the Weather Girls and Dean were ‘gay’ only by an association to which most were oblivious. Which leaves only ordinary gayboys Bronski Beat and their pervy polarity, Holly Johnson and Paul Rutherford still, ah, standing.

The reason for this reticence was that the 80s were as homophobic as they were homoerotic, an extension of the backlash expressed by Disco Sucks. Reagan and Thatcher left AIDS to gut gay communities, Manchester chief constable James Anderton derided gays’ “cesspit of their own making”, gay icon Donna Summer was reported to have turned on AIDS sufferers during a concert (which the singer later strenuously refuted), Bowie denied he’d been bisexual and Queen’s drag video for ‘I Want To Break Free’ killed off their American career. Yet, that symbiosis between repression and regeneration means that the queering of 80s culture was equally Reagan and Thatcher’s doing. Intended to break union militancy, deindustrialisation had the unintended consequence of unmanning masculinity – not just in work but in play, displacing denim and drumkits alongside hardhats and heavy machinery. This creation of new space for women and queers is captured by the video for Olivia Newton John’s 1982 synthpop makeover ‘Physical’. With synths regarded as unmasculine and newly vogue gym culture derived from gay culture, in the video, personal trainer Newton-John whips slack-bodied men into musclebound hunks – who then pair off at the end. The radical potential within this societal shift was expressed in pop by the Style Council’s ‘Long Hot Summer’ video and in politics by the Greater London Council – a libidinal socialism that would put the ‘sexual’ in ‘revolution’. Yet with 80s deregulation enabling the monetisation of everything, a libidinal capitalism was an equally perceptible potential in the ‘Physical’ and ‘Rio’ videos and in Madonna’s ‘Material Girl’. So, for sonic svengali Trevor Horn and marketing mogul Paul Morley to create a surreally sexy corporation, ZTT, was to place their first clients, Frankie Goes To Hollywood at the centre of these polar possibilities. As Richard Cook put it in NME at the time, Frankie was an attempt “to strip pop naked by paradoxically clothing it more sumptuously than ever before” – Horn and Morley’s lavish, self-conscious promotion, packaging and production revealing the processes of the music business.

The danger was always that of the emperor’s new clothes – sellout dressed as satire – and contemporary reviews reveal the tide was already beginning to turn as Welcome To The Pleasuredome arrived on a wave of hyperbole. Now that 80s possibility is our reality, however, Pleasuredome’s perceived weaknesses seem more like strengths, tracking cultural change in real time. Frankie’s flamboyant merger of marketing and music was astutely on the money. With the album’s opening lines being, “Using my power, I sell it by the hour / I have it, so I market it”, a Reagan impersonator proclaiming Frankie “the most important thing this side of the world”, and proceedings ending with a ‘Frankie Says’ ident, the result is insight as much as incorporation. The producer eclipsing the players – the instrumentation being largely Horn’s synthetic wizardry, sections of the title track and the whole of ‘War’ and ‘The Ballad of 32’ being entirely Frankie-free – makes FGTH both voguely anti-rockist and a precursor of dance culture (before we even get to the plethora of different mixes). In this respect, even Frankie’s paucity of conventional songcraft was prescient. Horn called the original ‘Relax’ more of a jingle than a song, and while Horn’s version still has no verse, just a two-note chorus and killer middle eight, his machinations transform a track into an experience, managing to make machines sound sensuous. Pleasuredome’s revival of prog was equally ahead of the curve a decade before Dog Man Star (Horn had worked with Yes, whose Steve Howe plays on the title-track). As for Frankie’s exploitation of queerness, while it’s predictive of corporate capture, it also expresses a dizzily libidinal liberation.

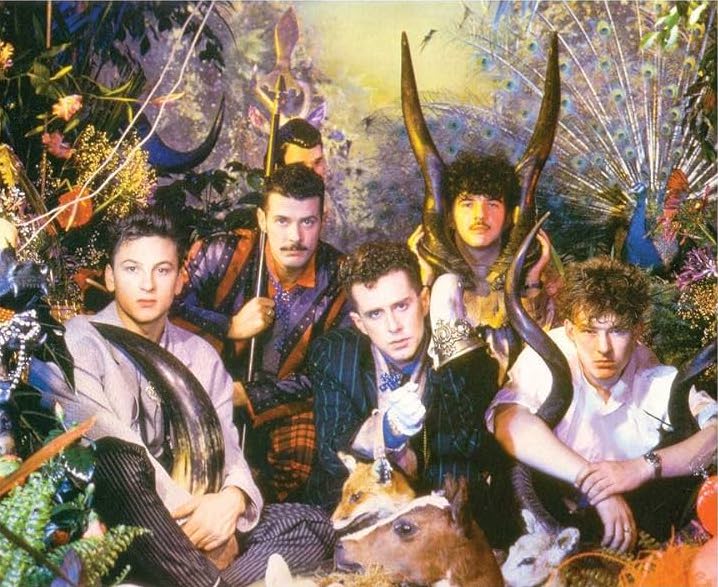

As the album’s title implies, Frankie were inviting their audience into a world of erotic possibility. The fact you can’t consider the band without their videos indicates how Frankie inhabited that music/marketing contradiction. Seen now, the ‘Relax’ video isn’t terribly shocking – there’s no actual sex and its BDSM is vanilla – but it being a straight’s idea of decadence is precisely the point. This was the marginal addressing the mainstream, not talking to themselves, as precursors Soft Cell sometimes seemed to be. Johnson’s portrayal of a nervous but enthusiastic rube provides public entry to this liberated world, for which Rutherford – as the band’s sexiest member – is gatekeeper and guide. The Lads being along for the ride makes them crucial – rather than tangential – to such a project. So, the video’s hints of horror play on what normies might imagine, with the tiger Johnson is fed to a metaphor for such fears – which he doesn’t just overcome but gives a great big kiss. Although the sumo’s eruption of piss/semen across the club is as grossly literal as the accompanying cry of “cum!”, it renders orgasm metaphorical, the libidinal release that Herbert Marcuse called ‘Eros’, the life-drive.

This should make ‘Two Tribes’ a celebration of Thanatos, the death-drive, with “sex and horror” the branded link between the tracks. Yet ‘Tribes’ eludes precise positioning: what do Frankie Say? Its ambiguity derives partly from its fragmentary form – an annihilating riff and killer chorus alongside some slogans – partly its production (the vocals don’t arrive til 5 and a half minutes into the CD mix), while in the video, Johnson, again our entry-point, is a news anchor, hence officially neutral. So ‘Two Tribes’ can be read as libidinal nihilism – nuclear war a terminal version of ‘Relax’s orgasmic release – its ‘transgression’ a fatalistic acceptance of the status quo (very postmodern). Or ‘Tribes’ can be read as a protest: in the zero-sum existentialism of “a point is all you can score”; in the grisly public information announcements about tagging dead grandmothers, and by being preceded by a fragment of Frankie’s version of Edwin Starr’s ‘War’. Horn and Morley can’t help muddying the waters, however, and have a Reagan impersonator run Hitler speeches into Marxist theory. So this could be Frankie calling Reagan a fascist – as precursors Heaven 17 had – or it could be horseshoe theory (left and right meeting at poles), were David Graham Cooper’s lines about “revolutionary love” not so powerful. For ‘War (Hide Yourself)’ offers a rare reassertion of countercultural collectivity amidst 80s individualism: “for… Che or George Jackson or Malcolm X, love was the prime mover of their struggle – that love cost them their lives.”

Aptly, the title-track encapsulates Frankie’s contradictions. ‘Welcome To The Pleasuredome’ is a 14-minute production tour de force despite being a corporate merger of ‘Relax’ and ‘Two Tribes’; a sumptuous piece of pop despite its one-note verse melody making recitative sound tuneful, and a conceptual masterstroke – inviting the mainstream into the margins again – despite Johnson’s lyric being a collection of unrelated one-liners. “The animals are winding me up”; “in Xanadu, did Kublai Khan a pleasure dome e-rect!”. This makes the track both a celebration of the transgressive world and a caution about its pitfalls. Rather than being passengers this time, The Lads drive themselves to the Pleasuredome to taste its forbidden pleasures, and the fact that they all come to grisly ends in the video’s narrative (despite bassist Mark O’Toole prudishly keeping his trousers on) emphasises the cautionary aspect – while the sheer seductiveness of the track enacts the celebratory.

The third of Frankie’s 1984-conquering number ones, ‘The Power of Love’ could be seen to contradict all the above: by being a proper song, by having a verse and a chorus, by being played by the actual band alongside a (real) string section, by being more conventional than queer – what are those “pretty girls” doing here? – and for seeming more sincere than ‘meta’. Yet while ‘The Power of Love’ is a celebration of 80s emotional privatisation – “I’m so in love with you” – it’s also a last hurrah for the countercultural “revolutionary love” cited in ‘War’: a “force from above” whose power “keeps bad at bay”. The recurring “make love your goal” could be either a political statement – ‘make love not war’ – or a personal one: the goal to get it on. The accompanying video of Christ’s nativity invokes love’s wider application but is equally a flagging of festive-targeted marketing (which didn’t quite snag the coveted Christmas top spot).

Regarded as a corporate delivery system for its singles, the rest of Welcome To The Pleasuredome has been lost to history – somewhat undeservedly. ‘Krisco Kisses’ pursues the ‘high concept’ – and low melodic content – approach, being a paean to pervery: “with a fist way up to the wrist… you fit me like a glove… you can take it up”. The half-rapped, proto-house ‘The Only Star In Heaven’ is a corporate motivational address – “Enjoy it or get out the game / It’s such a shame to lose again” – extended to personal life – “live life like a diamond ring” – which might or might not be serious. However, CD addition ‘Happy Hi’ proposes a polar approach – “why in this life must we work life like a deal?” where “life is like a train” – a muted cry for help from the centre of the vortex, underscored by a lovely ricocheting synth-riff. The charming ‘Wish The Lads Were Here’ may be content-light but it’s melody rich, while the brilliant ‘Black Night White Light’ could have provided another hit given a bit of a buff and polish. Its sketched lyric invokes Frankie’s upholding of possibilities both negative and positive – “Heaven’s above and hell’s below” – as these “pleasure seekers” repeatedly proclaim “we are the leaders” – which, for a year, they certainly were.

Frankie owned 1984 because that’s when the cultural space opened up for such a project, with the possibilities all in play. But in the 80s’ accelerated temporality, that space was shut down by 1985, the worst possibilities becoming realities. With corporations gaining an even greater cultural grip, queerness was parcelled off as a consumer demographic, and in parallel, traditional masculinity was reasserted, with music readopting rockism (from Eurythmics’ 1985 Be Yourself Tonight to Frankie’s own, redundant 1986 Liverpool) and rave revitalising laddism from 1987. Which explains not just Frankie’s inability to follow Pleasuredome – but anyone’s. Pet Shop Boys’ archness and Erasure’s querulousness lacked Frankie’s sexiness, while Stock, Aitken and Walkman’s own production-led, production line tamed its homoeroticism for the teen market, had no meta-level to its commercialism, and was sonically Aldi to Frankie’s Waitrose. For a year, Frankie Goes to Hollywood possessed the contradiction between music and marketing and inhabited the liminal space between the queer margins and the straight mainstream. Welcome to the Pleasuredome was the pinnacle of that project, the final blowout which announced its imminent burnout.

Toby Manning’s Mixing Pop and Politics: a Marxist History of Popular Music is out now on Repeater