Compare and contrast: "The world is my oyster," the opening words to Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s debut album, 1984’s Welcome To The Pleasuredome. Delivered by Holly Johnson in the flippant style of a cartoon villain, a cackling laugh in their wake.

"I’m looking for something and I don’t know what it is," the last words to Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s second and final album, 1986’s Liverpool. Delivered by Holly Johnson in the style of a man running on empty, almost bereft of hope. What a difference a couple of years can make.

Frankie Goes To Hollywood first hit the top of the UK charts at the start of 1984 with ‘Relax’, a hedonist’s dream of a record. Margaret Thatcher had been re-elected the previous summer, cruise missiles were arriving at Greenham Common, the England football team had failed to qualify for Euro 1984, and Frankie were a welcome, colourful distraction. But back then Thatcher was still only sinking her teeth into the country. By the time its follow-up, the extraordinary ‘Two Tribes’, was available, Arthur Scargill (President of the National Union Of Mineworkers) had announced a national strike in protest at her closure of twenty mines in communities which largely depended upon them for work. When their third single ‘The Power Of Love’ was released at the end of the year, a divided nation had witnessed violent confrontations between police and pickets and been shocked by news of the senseless manslaughter of a taxi driver, killed by two striking miners who’d dropped a concrete block onto his car as he drove two strike-breakers to work. As ‘Welcome To The Pleasuredome ’emerged as a single in March 1985, the strike reached its official end, union representatives unable to reach agreement with management, beaten by a war of attrition that left them almost out of funding and which saw mining families so poor they had to scavenge coal from slag heaps, three children dying as a result. By the end of 1985, 25 mines had been closed since the strike started, and another 17 followed in 1986. (Of the 170 mines that existed in 1983, only six remained by 2009.)

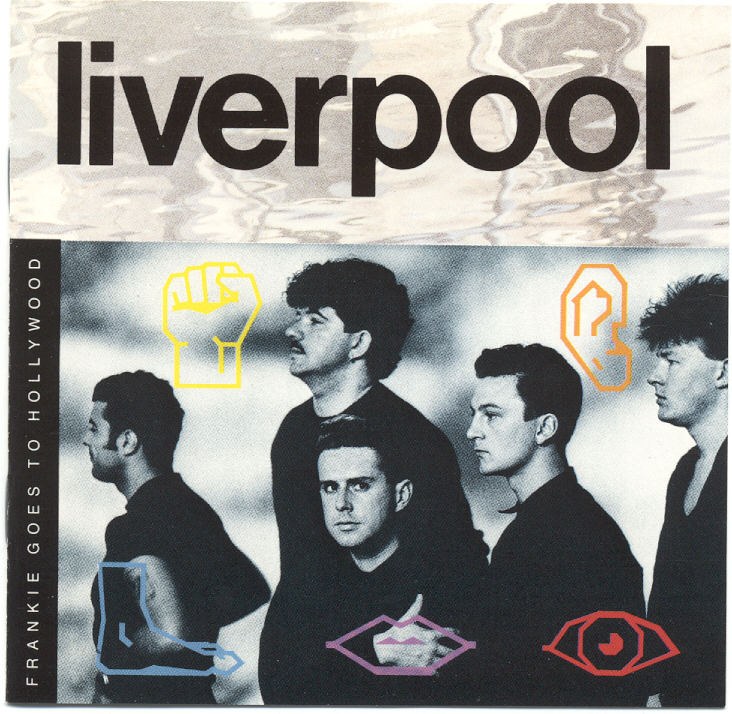

So it was a different country that greeted the release in 1986 of Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s second album, Liverpool. Unemployment had topped three million, and Thatcher’s unpopularity was such that even the University Of Oxford had refused her an honorary degree, an extraordinary snub given that every prime minister since 1945 had received one. Nonetheless, she still had half her second term of power ahead, and Frankie knew that the extravagance of Welcome To The Pleasuredome was out of keeping with the times. Liverpool was more overtly serious, something reflected in the black and white Anton Corbijn shots of the band. The day-glo colours and the sense of fun and mischief at the heart of their debut had disappeared, replaced by an often monochromatic vision, a seething anger and a raw sense of injustice. This wasn’t the Frankie we expected, five cheeky lads in leather waving plastic guns at us and revelling in sexual innuendo, the gang to whom we’d given our hearts wrapped in baggy T-shirts. But that was because two years earlier you could still lampoon the rival nuclear powers of the Soviet Union and America in a promotional video and call it an act of rebellion, just as the band had done with ‘Two Tribes’. By April 1986, the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant had caught fire and contaminated rain was falling from the sky. We were now beyond the pleasuredome.

Unfortunately, Frankie’s audience wasn’t ready to adjust. Whether fans would have welcomed back the cartoonish antics of the band’s former existence can’t be said, but they weren’t capable of adapting their expectations so acutely. There seemed to be a ‘disconnect’ between the Frankie they’d known and the Frankie that returned to rage hard against the machine. The band’s mood was different, their sound was different, the whole vibe was different. They’d moved from the vivid, surreal landscape of their debut to the gritty streets of the band’s hometown, and the leap was too great for most to take. So, inevitably, whether you considered it commercially or critically, Liverpool was, at least in comparison to what had preceded it, a failure. It didn’t contain a single UK number one and the reviews were largely scathing. It presaged the band’s imminent breakup and subsequently an ugly court dispute between the label and Holly Johnson. It baffled their fans, provided ammunition to their detractors, and remains little more than a footnote to their short history, a blot on the landscape of an otherwise exemplary 80s pop band. Liverpool quite simply bombed.

ZTT’s new reissue of the album, complete with another hundred plus minutes of bonus material and packaged in a typically lavish case, is an attempt to correct that. It’s a hopeless task, of course: no one can be under the illusion that Liverpool is a classic album, and much of the bonus material further underlines that, revealing a band torn – like the UK – between two opposing forces, this time the playful idealist that was Holly Johnson and the fun-loving lads that backed him up. Yet there’s something fascinating about it. Amidst its misfiring bombast and desperation there are plenty of memorable moments, some of which benefit from our separation from the album’s context, others that are given new value when we look at it as a document of its time. It reflects a changing political landscape – and make no mistake,Liverpool is frequently a political album – and also serves as some kind of metaphor for the country in which it was shaped, the product of two opposing convictions utterly at odds with one another.

Liverpool‘s weakness, to cut to the chase, is that many of its songs just aren’t very good. Though it undeniably has its moments, it’s musically ill focussed, stylistically inept and – after the banquet that preceded it – disappointingly unsatisfying. It’s the sound of a band trying to prove who they are before they have found out what that is, coming to terms with massive international success yet confronting the fact that it wasn’t on their own terms. It was often said, after all, that Frankie weren’t a band: they were merely ZTT’s puppets. It didn’t matter that they had existed long before Trevor Horn began his work on ‘Relax’: the rumours claimed that none of them could actually play and that even Johnson’s contribution was minimal next to that of the producer and his team (something that later became the focus of Johnson’s court case). They were, apparently, a marketing scam, a manufactured entity, a practical joke at our expense. Had they not been rescued from gay nightclub obscurity by a killer song, a groundbreaking producer and a Synclavier, "one," in the words of ‘Two Tribes’, could have been "all that they can score". This, one suspects, stung. Frankie were indeed a band, and they were musicians, and they didn’t need to follow the path that ZTT had laid out for them. They’d write their own material. They’d help produce it. They’d recreate themselves. They’d show the world what Frankie really had to offer.

The problem was the division between the two factions, Holly Johnson (vocals) and The Lads – Paul Rutherford (vocals, keyboards), Brian ‘Nasher’ Nash (guitar), Mark O’Toole (bass) and Peter ‘Ped’ Gill (drums). You can see it from the cover shot on this reissue, the musicians all looking to the left while Holly Johnson looks straight into Corbijn’s camera. (Another version of the cover used five separate portraits, further emphasising the lack of camaraderie.) Both parties had legitimate reasons to insist upon change – both wanted to be taken seriously – but their goals were different: the Lads wanted to be recognised as musicians, while Johnson wanted to prove they had something to say. And, of course, the referee had his own agenda: ZTT Records wanted to maintain the high levels of success their cash cow had already achieved and, whether Frankie liked it or not, ZTT remained their paymasters. With such forces all pulling in opposing directions, the album could not help but sound strained.

Even the record’s title was seemingly a decision taken out of the band’s hands. According to Johnson, quoted in the sleevenotes, "it should have been called From The Diamond Mine To The Factory because I thought that described well the transformation from being in Liverpool and being creative, and then becoming absorbed into the mainstream of commercial activity." As he mourned the passing of his original title you could almost hear him groan when he added, "but no one else is really that intent about things. That’s just me…" Perhaps he was laughing as he said it, but there was no doubt real disillusion lay behind that remark. Clumsy it might have been, but From The Diamond Mine To The Factory (the opening line to ‘Warriors Of The Wasteland’) did indeed encapsulate the bewildering experience the band had undergone in recent years. Liverpool, in comparison, didn’t really say much as a title, even when one takes into account the rumour that it was once called Liverpool… Let’s Make It A Double, something that the football team might have been able to manage that season but that the band clearly couldn’t pull off. Rutherford tried to justify the decision, helpfully pointing out to Smash Hits that, "we all come from Liverpool," though he still couldn’t help but concede, "even though we don’t live there now". Johnson, however, was by now well attuned to the machinations going on behind him. "For me the title Liverpool is just incidental, it’s marketing," he argued bitterly in an interview that was published even before the record came out. "I think they (ZTT) liked it because they could go, ‘Ooh yes, they’ll love the title in Japan and America’ which I think is sick."

So Johnson The Artist, his rowdy acolytes The Lads and their patrons ZTT circled around one another, trying to find common ground and settling finally upon Liverpool. It was, one suspects, a similar process to that which lay at the heart of the album’s creation, a complex gestation that had seen Trevor Horn step back into an executive producer role while Steve Lipson sat behind the desk, and which found them working in six different locations in Ireland, Ibiza, Holland and the UK. There, while Johnson pored over lyrics inspired by T.S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, Walter Hill’s 1976 ‘Warriors’ film and, especially, Thatcher’s divisionist policies, the band cranked up the volume. The 80s were, as ZTT’s reissue curator Ian Peel astutely points out, when bands "’went rock’. (They) felt, mistakenly in hindsight, that they had to prove they could play live, and front up as well on The Tube (where you were forced to play live) as they could on Top of The Pops (where they were forced to mime)." So amps were turned up to 11, and as they ‘rocked’, fridges were emptied. In that same interview with Smash Hits, also quoted in the sleevenotes, O’Toole revealed that the song ‘Lunar Bay’ "sounds a bit drunk oriented… Most of them are. We were totally drunk when we recorded them, and when we wrote them." Even O’Toole’s attempt to revise that comment in case it sounded belittling of their work came off awkwardly. "It’s not that we don’t take all this seriously," he hurriedly correctly himself. "We take it all totally seriously. But we just get pissed at the same time."

No wonder so much of Liverpool sounds desperate, with Johnson’s and The Lads’ working methods and ideology so hard to reconcile. There had always been an over the top element to the band’s music, but it hadn’t involved the kind of squealing guitar solos one might find on Survivor’s ‘Eye Of The Tiger’, and Johnson sounds frequently completely at odds with his surroundings, the band’s previously exciting bravado punctured by flatulent muso posturing. But, when they first stepped back into the spotlight, things didn’t look quite so bad. Special mixes (included on the bonus CD) of ‘Rage Hard’ and ‘Warriors Of The Wasteland’ were unveiled at the Montreux Rock Festival that was broadcast on UK television, and though it suggested the band had muscled up there was still a drama and exhilaration evident that had been such a big part of their appeal. First single, ‘Rage Hard’, suggested especially that their work had been worthwhile. Sure, it didn’t take long for the first guitar to wail, but there was enough that remained recognisable for their fans to send it to number four in the charts. United behind Johnson’s call to arms – "Rage hard, into the light / Rage hard, doing it right, doing it right / Rage hard, against the dark / Rage hard, make your mark" – Frankie were back with a bang. ‘Warriors Of The Wasteland’, though, was a little puzzling, its chugging guitars weighing the song down and suggesting that they were readying themselves for an all-out assault on the American rock market, where Europe’s not entirely dissimilar ‘The Final Countdown’ had proven that Europeans could gain a foothold. It implied the band could play their instruments, perhaps, but it still sounded leaden compared to the thrill of ‘Two Tribes’ or, frankly, Bon Jovi’s ‘You Give Love A Bad Name’. Even O’Toole admitted to Smash Hits that, "we nearly kicked this one out (because) it sounded so like Spinal Tap when we wrote it". Furthermore, it was obvious from their televised appearance that they weren’t actually performing live anyway: during their performance of ‘Rage Hard’ Johnson is seen but not heard to sing lines that had actually been excised from the mix. It was a clumsy return, indicative of the album that was about to be unleashed to a rapidly diminishing legion of fans.

Still, Johnson remained the heart and soul of the band, and his contributions were largely worthwhile. Clearly disturbed by contemporary events, he carved out his new lyrical ground, addressing the class divide with some genuinely impressive lines that, in many ways, remain pertinent today. ‘Warriors…’ alone contained a fair few nuggets: "It seems to me that the powers that be / Keep themselves in splendour and security", "They make the masses kiss their assets" and "Your job is gold / Do what you’re told" all vying for quotable status. ‘Kill The Pain’ meanwhile called upon its audience to "Breaks the chains / We can rise up again / Once we’ve rearranged the nature of the game", and ‘For Heaven’s Sake’ echoed these sentiments with a pointed reminder that "We’ve done what’s right, you’ve done us wrong", Johnson counselling us with the wisdom, "For heaven’s sake, we got to break away / Unchain yourself, from the mood of today". The song also contained a transparent reference to Thatcher herself, a note of wit sadly otherwise absent from the record: "She should buy us all a drink / She should stop and think".

But elsewhere Johnson sounded like he just couldn’t be bothered to make the effort to rise above his deteriorating accompaniment, his belief in the tyranny of the system unable to excuse tired rhymes like "We don’t need recession / Nor means of repression / Just give us some money / Our life could be sunny too". Even when he tried to focus on less political subjects he sounded awkward. ‘Kill The Pain’ finds him uttering nonsense like, "I’ll follow you to fires of hell / And cast my soul in wishing wells / The colours of the shredded sky / Hear the children sing", while ‘Lunar Bay’ sinks to levels that even Hallmark would reject: "Feel me walking in the sun / Hear me talking to the moon / I won’t change for anyone / I’m just for you". He reached his nadir with ‘Watching The Wildlife”s exhortation to "Get free from hate and get in love", something even a hippy commune would reject for its inelegance.

Meanwhile the band railed around him as though they’d swapped their leather bondage for spandex trousers. Johnson might still sound committed, but the clunky ‘Kill The Pain’ sounds like it was held together with sticky back plastic, so weak that it collapses in upon itself as it grinds towards its long overdue end, and their final single, ‘Watching The Wildlife’, is quite simply wretched, compiling the very worst of Europop, Metal Lite, stage musicals and easy listening into four teeth-grindingly cliché-laden minutes. They couldn’t get it this wrong throughout, however: ‘Rage Hard’ did exactly what it said on the tin, and ‘Maximum Joy’ stripped back the arrangements to let the Synclavier take central stage once more, diva operatics decorating a genuinely uplifting song full of peculiar but strangely captivating flourishes before opening out towards its conclusion. ‘Lunar Bay’ featured an invigorating drum track that rattled fiercely, helping the track build up a head of steam until it reached a typically ZTT breakdown, its synthetic brass, breaking glass and Johnson’s unique grunts and wails not a million miles from the proto-industrial pop of labelmates Propaganda. And of course ‘Warriors Of The Wasteland’ was abrasive, while there was also a certain lighter-in-the-air appeal to ‘For Heaven’s Sake’, a song calling out for an arena that was no longer theirs, though the sense that its bridge had been hurriedly stapled to the rest of the song reduced its impact just as it should have been climaxing.

Liverpool‘s highlight was the album’s closer, ‘Is Anybody Out There’, possibly an attempt to regain territory they’d claimed for themselves with ‘The Power Of Love’. It was a poignant mixture of regret, passion and sorrow that highlighted Johnson’s faith in selfless compassion as a saving grace – "The highest price I’d gladly pay / For you to live just golden days" – whilst conceding that the only way to survive in a world where "children are dying and nobody’s crying" is to adopt a sense of ‘carpe diem’: "Give me real life, the worry and the strife / I’ll throw it out of the window to the dogs below". Johnson sounds completely at home here, the sparse arrangements allowing his voice to shine as he indulges in visions of a better life: "Come with me / I’ll guide you through wardrobes of fantasy / And treasure chests of what could be / A world without anxiety / A legacy of golden days". In fact, the song alone is almost enough to justify Liverpool‘s existence, and survives now as a lament for what might have been possible if the band hadn’t been simultaneously tearing itself apart. "If I could change the things I’ve done," Johnson sings at its start, "would I be the only one?" and it’s hard not to experience simultaneously a huge sense of disappointment at the knowledge of what they had by now squandered.

Still, it’s best that they left before they did any more damage to their legacy. Frankie were clearly a spent force, something that many of the bonus tracks emphasise painfully. B-sides included a hideous and entirely unforgivable version of ‘Suffragette City’ and the cut and paste theatrics of ‘(Don’t’ Lose What’s Left) Of Your Mind’, which featured belching as part of its percussion track and what sounded like Sesame Street’s The Count ordering "a coffee, a burger" amidst a Transylvanian thunder storm. Previously unreleased covers of ‘Roadhouse Blues’ and ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’ suggest they’d have struggled to get a gig at the Half Moon in Putney, and we can only be thankful that we’ve been spared further shameful indulgences such as ‘Anarchy In The UK (The Lads Giving it Loads)’ and ‘Sex Machine’, the tapes for which, curator Peel reveals, remain in the vaults, as do other curios with titles such as ‘Pig’s Ear or ‘F*** Off (Monitor Mix / Wisseloord Sessions November 1985)’. Even the extended mixes – a groundbreaking source of joy throughout the Pleasuredome campaign – sound like they were put together on autopilot, the interminable 25 minute ‘Wildlife Cassetted: Orchestra Wildlife / Watching The Wildlife (Hotter) / The Waves Bit 1 & Bit 2 / Frankie Condom Mix (For A Wilder Time)’ as tedious as its name and really only notable for the odd inclusion, halfway through, of the rare minimalist B-side, ‘The Waves’.

Liverpool signified a miserable end, summarised by a short excerpt of recordings by Pamela Stephenson for a cameo appearance (here entitled ‘Pamela’) on a ‘Rage Hard’ 12": "Frankie Goes To Hollywood. 1986. What a relief. The B side. The End. I could do with a coffee and a burger." The world had been Frankie’s oyster, but the speed with which they ascended, and their failure to orientate themselves once they’d reached the top, left them concussed. Their rise and fall is, like the miner’s strike, a metaphor of sorts for the 80s, a representation of how destructive failure to find a shared and common good can be, a warning of the dangers inherent in forsaking one’s values. Similarly, both are things which, at their worst, are best forgotten, but which also provides in their own way, evidence of the power of unity and understanding. Strong words for a mediocre album, you might think, and you’d have a point, yet everything Frankie did was writ large, and their failure, encapsulated within these 44 minutes, was somehow suitably spectacular.Liverpool was a hoary blowout, but it was still punctuated with several moments of well-focussed fury and grace that are worthy of their legend. One suspects that, if we could change the things they’d done, we wouldn’t be the only ones, but there’s something enthralling about trying to work out from the album’s strengths what Frankie would have found if they’d only known where to look.