Things were not looking up in 1974. From oil-crisis-induced austerity to Watergate in the US, the West was undergoing a pan-cultural nervous breakdown. Bad vibes abounded at every turn; the hippie dream deferred, as clear in the headlines as in Hollywood. But no cultural document captures that era’s transitional unease better than June 1, 1974, an art rock meeting-of-the-minds that placed luminaries Kevin Ayers, John Cale, Nico and Brian Eno before a bewildered live audience at London’s Rainbow Theatre. Released fifty years ago this month, its potency – and oddness – remains intact.

Its mythology also looms large. Even today, the record’s calling card amounts largely to the affair occurring between Ayers and Cale’s then-wife, Cindy Wells, the night before the performance. The salaciousness of that encounter – and its resulting whiff of scandal – has limited the record’s legacy in the decades since, an unfortunate distraction regardless of its myth-making power. (Wells had already been sort-of memorialised in Eno’s ‘Cindy Tells Me’ the previous year; Ayers would receive less favourable treatment following the affair, described as “the bugger in the short sleeves” in Cale’s ‘Guts’, an album track on 1975’s Slow Dazzle.)

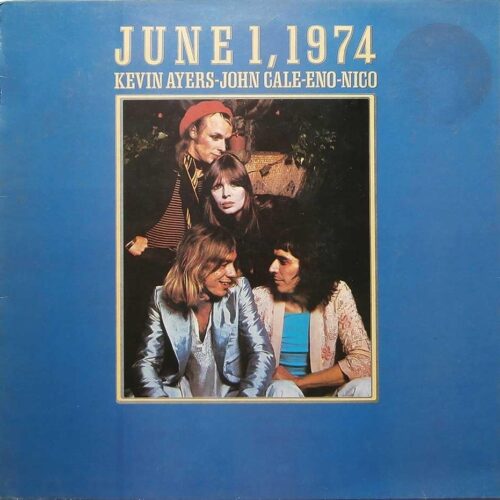

The tension is apparent in Mick Rock’s delightfully decadent cover photo. Immediately, we’re face to face with our subjects in various technicolor shades of satin – or, for Nico, jet black – and Eno’s cherry-red beret. Cale and Ayers are seated in the foreground, gazing at each other with sheepish amusement (Ayers) and confrontational intensity (Cale).

Not pictured are the night’s slew of backup players, most notable among them Mike Oldfield, Phil Manzanera, and Robert Wyatt. (Eerily, this concert also marked the one-year anniversary of Wyatt’s fall from poet “Lady” June Campbell Cramer’s fourth-story window in Maida Vale, rendering him paralysed from the waist down. Two benefit concerts organised by Pink Floyd – and presented by a young John Peel – were held at the Rainbow the previous November.)

In the preceding weeks, an eager music press fanned whispers of a Velvet Underground reunion – with Eno replacing Lou Reed. (After all, Reed, Cale and Nico had spontaneously reconvened at Parisian venue the Bataclan in 1972; maybe it could happen again?) But as Eno would recall to Creem’s Richard Cromelin: “I didn’t want to go on stage to be judged as Lou Reed’s replacement. People would come along and expect me to sing ‘Heroin.’”

In reality, the buzz of a rumoured Velvets/Soft Machine super-summit obscured how much cross-pollination had already occurred between the four involved. At the time of the show, Eno was busy assisting with Cale’s Island Records debut, Fear, which itself “gave birth to the possibility of the June 1 concert,” as Eno would tell Hit Parader in 1975. Four years earlier, Cale produced Nico’s plaintive Desertshore, a record whose title Ayers name-checked in his own ode to Nico, ‘Decadence’, on 1972’s Bananamour. No doubt, Eno’s later-conceived idea of “scenius” was well underway. But for the post-hippie music scene, the lure of something “super” was strong, and any talk of a supergroup would likely face a bull market.

The foursome – not-so-lovingly named “ACNE” in the Gasbag section of NME – had until then occupied only the more far-flung corners of rock’s vanguard class. Accordingly, few would have pegged any of the quartet ripe for supergroup billing. (If anything, Oldfied, fresh off the Exorcist-indebted success of 1973’s Tubular Bells, had the nearest claim. The 18 May cover of Melody Maker featured a splashy preview of the gig, touting, in order: “Oldfield, Eno, Nico – Live!”)

Nevertheless, Richard Williams, the newly minted Island A&R and former Melody Maker editor himself, was eager to draw attention to the label’s more outré recent signings. As he recently recounted to Uncut, the idea was hatched “over a lunch for five at an Italian restaurant called Gatamelata on Kensington High Street” on 13 May – less than three weeks before the concert. With a knowing nod to the more ear-to-the-ground crowds Williams and his label were surely courting, the accompanying LP would be intended “as a kind of official bootleg.”

A more likely rationale, says David Sheppard in the Eno biography On Some Faraway Beach, was Williams’ attempt to gin-up hype. He had been searching for a way to recoup the squandered advances to Ayers’ follow-up to The Confessions Of Dr. Dream And Other Stories, released on Island earlier that year. The concert and ensuing live album, Sheppard writes, thus served the dual purpose of capturing a new set of Ayers material while lending Eno, Nico, and Cale – all recent Island signees – some “much-needed oxygen of publicity.”

The concert sold out quickly but the resulting album enjoyed a cooler reception. Recorded by John Wood via the label’s mobile studio, only select highlights from the evening would be chosen for the resulting LP: a sampling of each of the four players, with Ayers encompassing the entirety of the second side. It was rush-released at the end of the month and failed to chart.

Audiences, it seemed, were still on the hunt for new heroes. Despite a younger UK music press “now largely staffed by writers who knew about the Velvets and the Soft Machine,” as Williams recalled, the search continued.

The mainstream rock landscape offered few clues. Prog was quickly spiraling into self-parody; the Stones were exchanging tax exile for mid-tempo assurances that their schtick was now “only rock‘n’roll,” so completely masking their original danger that you could now take them at their word; even Bowie and Bolan seemed aware that glam’s time was up.

Roxy Music’s debut offered a much-needed corrective to the ossifying myths of rock’s late-60s heyday. But despite their suggestion of the market potential for that heyday’s artier, lesser-known strains, a larger sea change was inevitable. And though punk’s stripped down brutality wouldn’t fully crystalise until late the following year, its sense of chaos and confrontation were very much on display at its 1 June vernissage.

Eno began the night. The set’s nightmarish tone is apparent from the top, with Eno delivering deliriously ecstatic and mechanistic versions of Warm Jets highlights ‘Driving Me Backwards’ and ‘Baby’s On Fire’, the latter featuring a Roxy-plundered Manzanera on guitar.

Next were Cale and Nico, who were more concerned with exhuming the graves of recent rock & roll past. Cale’s caterwauling take on ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ reaches heights (or depths) far exceeding Elvis’s original; and Nico’s saturnine version of The Doors’ Oedipal odyssey ‘The End’ worked as a double-eulogy to her soulmate-in-absentia, Jim Morrison, and the doomed era he embodied. Both tracks would become central fixtures in their respective catalogues, each artist applying their singular lenses to not just remake or remodel but reimagine completely the possibilities of the rock form. Their contributions are shockingly effective, proving why rock was in such desperate need of an autopsy more thorough than, say, Bowie’s Pin Ups to fully break with its dead-end past.

Ayers’ set, by contrast, was mellower and more straightforward, typifying his elegant wino-on-permanent-holiday mystique. Buffeted by characteristically louche renderings of the folky ‘Stranger In Blue Suede Shoes’ and the slightly creepy ‘May I?’, Ayers was joined only by backing singers and his band. (Eno, Nico, and Cale were backstage toasting celebratory champagne, emerging only for the valedictory jam ‘Two Goes Into Four’ and a bookending reprisal of ‘Baby’s On Fire’, which was not included on-record.)

Frustratingly – but fittingly, in hindsight – many of the night’s more interesting moments were left on the cutting-room floor, emerging only on sought-after bootlegs. Completists might mourn the loss of Ayers masterpiece ‘Whatevershebringswesing’, featuring a moving solo by Oldfield; early previews of Cale’s Fear classics ‘Gun’ and ‘Buffalo Ballet’; and Nico first pushing audience buttons with ‘Deutschland Uber Alles’. (She would provoke a near-riot when she performed it alongside Cale and Eno in West Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie later that summer.)

Even the show’s creation myth could have been juiced further. One of Ayers’ final songs was the giddily lecherous ‘I’ve Got A Hard-On For You Baby’ – still yet to be released anywhere – that saw Ayers joined by Cale on the titular refrain, the prior night’s infidelities notwithstanding. Such was the strength of their devotion to the event’s collaborative mission.

Eno understood that mission from the jump. As he stressed to Hit Parader, supergroups to that point had been a “disaster” because they tended to bring out “the lowest common denominator” of all involved: “You don’t bring out the best points in them, you bring out the points where they all agree, which is way down here.” Against that background, June 1 was a success, he said, because it instead pioneered “the idea of the superstar get-together.”

There’s something to this subtle shift in phrasing. Maybe it belies a more substantial shift in stakes or expectations: it likely played to ACNE’s advantage that no-one present, with the possible exception of Oldfield, would generally have been considered a “superstar”. But then again, maybe this wasn’t a “get together” in the come-on-people-now sense so much as it was a recasting of the original Warholian “happening” – and with it, Warhol’s Factory vision of the “superstar”. Perhaps Eno and Williams were reconjuring some of the Velvets’ art-world sensibility, adopting their pose precisely at the time their influence was finally on the rise.

Witness, too, how tidily June 1, 1974 fits within Eno’s larger theories of process, randomness (“honour thy mistake as a hidden intention”), and closed systems that would almost immediately thereafter become his stock-in-trade. Here, we’re given an early rendering of Eno’s “scenius”-as-system, where the individuals themselves are the cogs in a larger sound-making – or star-making – machine.

Eno was already reliably lending his VCS3-in-a-suitcase “treatments” to all manner of instruments in the studio. (Peter Gabriel dubbed it “Enossification” on 1974’s The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway; Wyatt would credit a similar process to Eno’s “direct inject anti-jazz ray gun” on 1975’s Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard.)

From the start, Eno’s knack for designing artistic workarounds and compositional “problems” afforded him a certain ministerial luxury: once everything was set just-so, he could stand back and let the machines whirr at will. On June 1, 1974, the machines happened to be the four artists themselves – along with a few auxiliary players of similar renown – whose only limitation seemed to be what practice time (or their various appetites) might allow.

Unsurprisingly, Eno adopted a managerial role during rehearsals, setting the song order and choreographing stage entrances and exits. He would later consider the project under-prepared, the inevitable result of duelling egos and Cale’s increasingly erratic behaviour and anxiety over his live debut. Nevertheless, as Sheppard put it, Eno “relished the idea of fusing musical like-minds into one, highly focused event.”

Such fusion would be short-lasting, as he explained to Hit Parader: “It was a very volatile situation and those are the ones that interest me in music. We weren’t sitting around patting each other on the back saying ‘groovy,’ ‘let’s blow together’ – it was quite intense.” (The two follow-up ACNE outings in Birmingham and Manchester were more modest. When Williams booked the foursome for a free festival in Hyde Park at the end of the month, only Ayers and Nico showed up.)

Of course, June 1, 1974 – its diary-date title almost demanding to be recognised in a fuller historical context – was itself a reflection of the times. With all its misadventures (both backstage and on), June 1, 1974 can be seen as an Altamont for rock’s imperial phase: glam’s pomp giving way to the paranoia, decadence and experimentation of its artier fringes.

Its constituent sets can also be read as a sort of Rosetta Stone charting rock’s disjointed trajectory through the decade. Within them, you can hear it all: punk’s squall in ‘Heartbreak Hotel’; post punk’s more angular and textural fixations on ‘Baby’s On Fire’; even Ayers’ luude-friendly folk balladry and Nico’s desolate harmonium are worthy alternative soundtracks to the decade’s creeping malaise and alienation.

Fifty years on, the night’s sense of foreboding feels even more prescient. Audiences still clutching to the last vestiges of ‘Free Love’ were quite literally met with the harsh 70s reality of Cale’s mewling viola and Nico’s funereal drone. This was the sound of “flower power” marooned on the desertshore, the hippie lapse into solipsistic indulgence bottled as an acidic Rhône Valley pinot, the very moment when all of glam’s hot stuff turned to flotsam. The nights in white satin had reached an end, and punk’s ink-black dawn – and, soon enough, Thatcher – were fast approaching.

That there’s evidence of ACNE’s meeting at all, then, is a minor miracle. Though the evening’s slapdash execution and patience-baiting sonic antics were likely as inevitable as its messy backstory, their uneven – but undeniably inspired – performances speak to the liberating potential of collaboration when the heavier star-marker machinery is cast aside.

Perhaps June 1, 1974 continues to resonate precisely because its ACNE namesakes declined to meet the outsized expectations that tend to accompany the “supergroup” tag. Instead, we’re given a competing vision of what a supergroup (or superstar) could be: Here was an anti-supergroup – one whose under-preparation, chance-worship, and anti-chemistry took precedent over peaceful easy feelings and commercial compromise.

Like the Beatles’ break-up (or Altamont itself), the “failure” of June 1, 1974 remains one of its greatest assets in the cultural memory. Above all, it demonstrates how lightning-in-a-bottle moments of shared spontaneity sometimes require upsetting expectations, a bit of impermanence and ephemerality, and a bit of dust for future uncovering – like Ozymandias in reverse. To quote Christgau (who got it right this time): “If there’s gotta be art-rock, Lord, let it be like this.”

So never mind the affair that long since overshadowed the record’s legacy – the triumph of June 1, 1974 lies in what it actually succeeded in capturing: a striking and at times terrifying snapshot of a cracked-up counterculture in transition, unflinchingly rendered by four artists who exemplified that transition like no one else.

Of course it was never going to be repeated.