Will Hermes

Inquisitive and comical, ‘Love Goes to Buildings on Fire’ is a 1977 song by Talking Heads, which is apologetic of life, its nonsense, or, if you prefer, prosaic simplicity. As in one of Tom Robbins’ novels, here love is defined in a bizarre manner; passing through architecture and bodies, Byrne enigmatically identifies such a beyond-words feeling with buildings and faces.

‘Love goes to buildings on fire’ is a bridge linking times and fashions; whilst it was firstly acclaimed as an early Television-esque composition, with hindsight we can argue that numerous bands, Pavement amongst others, lyrically owe a lot to the song’s epiphanic light-heartedness.

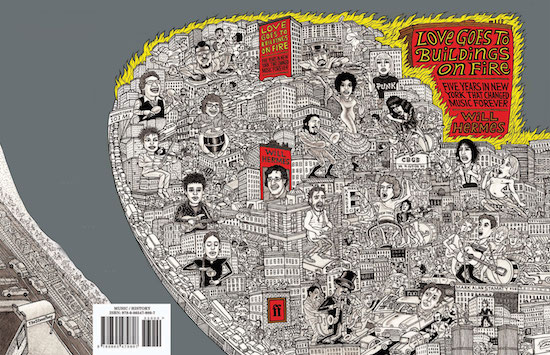

As to confirm its resonance throughout the years, the American journalist Will Hermes paid tribute to it when in 2011 he wrote Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: 5 years in New York that changed music forever. Now the book is out again, re-released and visibly displayed on shop shelves. Such exposure might be due to the fact that Hermes, a senior critic for Rolling Stone and contributor to NPR’s All Things Considered, has been announced as Lou Reed’s official biographer with his Lou: A New York life out on the market soon.

There is no visual separation between CBGB’s (and more) performers such as the Ramones, Debbie Harry, Patty Smith, Iggy Pop, Bruce Springsteen, and the New York cityscape; Hermes is interested in portraying the tight bond between people and their environment, showing how the two permanently yet mutably affect each other.

The writer minutely describes a conspicuous number of events in a limited period of time (from 1973 to 1977), which not only changed music but also influenced social conventions, behaviours, and collective aggregation worldwide. ‘Much has been written about New York City in the ‘70s, how bleak and desperate things were. [ ] And yet, down on the streets, artists were breaking music apart and rebuilding it for a new era’.

Hermes accurately researched anecdotal and thought-provoking material completing a book which is on the one hand a meticulous source of information, and on the other a way to understand the present as an extension (or less) of the past. Details never a gossipy flavour; they connect facts and provide the reader with the gift of context. Such wide scenery proves Hermes’ skilled devotion not just to long-term professional engagements but also to language, a tool in creating his visual epiphanies.

Numerous bands and solo musicians, whom Hermes likes to present with Homer-esque epithets (‘the expat viola player from Wales John Cale’), are mentioned as emblematic symbols of the time. Whilst the Queens-born journalist begins his story with the Modern Lovers’ ‘Hospital, a love song as raw as a skinned knee’ performed while supporting the New York Dolls in 1973, he concludes his odyssey describing Patty Smith and her active commitment to art. Thus, Hermes seems to be resolute and highlights his view on music and poetry as artistic creations feeding in to and off of each other; in this line of thought, the news of Hermes being Lou Reed’s biographer doesn’t seem a coincidence at all.

‘Of course, the impulse to fuse poetry and music had been in the New York air for some time – understandable in a city informed by the rhythms of jackhammers, subways, car horns, and people who won’t shut up’.

Throughout the book, great attention is paid also to artists’ sartorial choices, as to confirm the substance of form and the meaning of style theorised by Dick Hebdige in 1979: music is described as an event which goes beyond sounds and timed performances, profoundly influencing people’s way of living, beliefs, and social attitudes. For Hermes, not just David Johansen’s whiteness deserves – unsurprisingly – a few lines (‘he wore a white blouse, tight white pants, and white platform heels’) but also Patty Smith’s ‘faded Knicks T-shirt, skinny jeans, and the familiar black sports jacket’, as well as Alan Vega’s ‘radiation glasses’.

Hermes’ narration becomes reflective and self-questioning as he accomplishes a detailed report of the music journalism industry at the time. Not only does he provide the reader with numerous anecdotes on Lester Bangs, whose reaction to the news of Elvis Priesley’s death is accurately narrated (‘Lester Bangs was drinking beer with a friend on a Chelsea fire escape when he heard the news. He did a casual survey of the neighbors and was disturbed that no one seemed to care’), but also lists and describes the style and mission of various magazines and fanzines.

Hermes argues that New York’s most compelling music writer was Ellen Willis, and dedicates many lines to other female journalists/fans, such as the mother of rock Lillian Roxon, and Lisa Robinson who were capable of combining passion and smart insights: ‘Lisa Robinson wrote not like an insider or frustrated Ph.D. candidate but as a thoughtful, super-smart fan’.

Hermes neither interprets facts nor uses any captatio benevolentiae to make the reader believe in his particular translation; as a journalist, he is rather descriptive and avoids excessive critiques in favour of sticking to events and their provable resonance throughout the years. His words, far from being elusive, go straight to the point, as elements of a direct, picturesque, and incisive mode of storytelling. Surprisingly, if Hermes’ writing were a song it wouldn’t be the hermetic ‘Love goes to buildings on fire’, but rather the all-spitted-out kind of narrative of Suicide’s ‘Frankie Teardrop’.

The way Hermes describes New York is Scorsese-like; the reader can easily visualise kids playing dangerously and naively on the city’s streets or perhaps discovering two dead bodies in a pink Cadillac; New York is portrayed as the city where anything can happen, where the wise guys have the licence to steal. Hermes pays homage to a period often considered ‘a cultural dead zone’. Despite such belief, that time has been inspiring and creative as to confirm that ‘sometimes the worst situations produce the deepest beauty, and the most profound change.’

Hermes loosely divides the book into genres (punk, salsa, hip-pop) that in the ’70s were yet to be born, now music paradigms. He is skilfully capable of re-enacting not just facts but also the atmosphere of such a poietic time; his book with its encyclopaedic taste (despite being only 306 pages long) will be easily memorable as an influential and absorbing compendium of this creative period.

However, the reader, when it comes to the writer’s few biased opinions, is free to agree or disagree; on the one hand, Hermes makes praising statements about the importance of those Dictators, sometimes unfairly disregarded by literature and critics. The band played in fact an important part in the development of the punk scene in New York and worldwide: ‘the Dictators deserved as much credit for inventing the music as any New York band’.

Moreover, Hermes’ accurate and quasi-emotional account of Arthur Russell’s life is charismatic and captivating, mirroring the considerable interest the work of the Iowa-born composer receives nowadays. Such attention doesn’t come just from other musicians and music critics, but also from the visual art field, with numerous contemporary practitioners giving the deserved credit to Russell’s maverick persona (for example, see the video work ‘This is How We Walk on the Moon’ by Swedish Artist Johanna Billing). On the other hand, arguably, is Hermes’ vision of Patty Smith as co-owner of ‘My Generation’; ‘The Who’s ‘My Generation’ which has been part of her repertoire for so long, she’s really a co-owner of it’.

Having admitted that no artist writes on a blank paper, as to say that influences (subconsciously) guide any work, wouldn’t it be unfair not to recognise the difference between a great piece of art and one of its versions? Is there a discernible-enough dissimilarity between prototype-like compositions and their adaptation, or, are covers, after all, post-modernly originals?

Love Goes to Buildings on Fire is out now, published in hardback by Faber & Faber and Viking in paperback