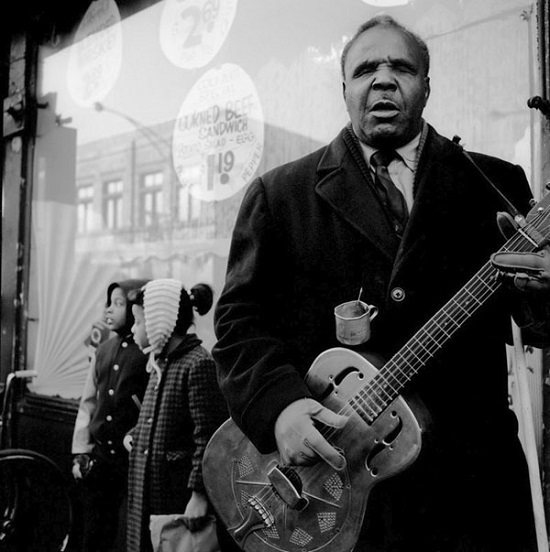

Imagine winning over 100,000 photographs by an unknown female photographer in an auction. Then imagine, as you slowly go through them, over weeks and months, that what is presented to you is one of the most profound and complex photo histories of New York during the 50s and 60s.

The story of Vivian Maier is an intriguing one. Fame only coming to her after her death. Unknown and undocumented, this nanny for the children of the wealthy was, on a daily basis, obsessively taking photos and storing them in an locker without a word to anyone.

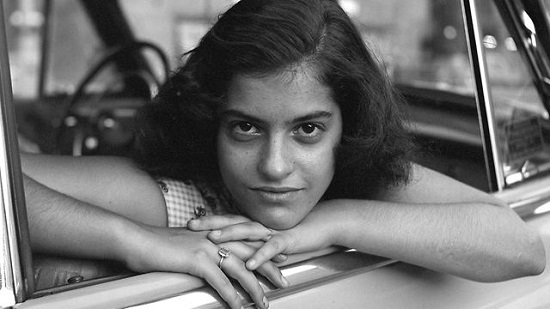

Not much could be gleaned from Vivian’s life bar from the people who claimed to know her, all with differing stories about the person she was. One thing was apparent though: her talent. Using a Rolleiflex camera, hung low, at hip level and looking down into the lens, she could photograph people intimately, often without being noticed.

Finding Vivian Maier is an intriguing film about an overlooked artist’s work nearly being lost, a life perhaps never fully actualised, and a person who even after her death continues to challenge and command respect. I spoke to the director Charlie Siskel (who’s previous production credits include Bowling For Columbine) about this unique film. I asked him for his thoughts on Vivian, her work, and what she can teach other artists living on the fringe of what society expects of them.

How did you come to be involved in the film?

Charlie Siskel: I learned that Vivian Maier’s work was nearly lost – someone found it in a storage locker. That’s how we all saw her work for the first time. I’m originally from Chicago so even though I was living in Los Angeles, I learned about the first show when it was mounted at the Chicago Cultural Centre.

I grew up in Highland Park, Chicago, which is the town where Vivian was a nanny. That was an odd coincidence. It turned out she was a nanny for a family that lived around the corner from my parent’s home.

The ravines, where Vivian took the kids to play, were in my backyard. The kids she was nannying were just a few years older than me so I know that during the 1960s and early 1970s Vivian was in the neighbourhood. It’s a small town and I’m sure I would have crossed paths with her.

There wasn’t a film at the time (of the exhibition). It wasn’t until about a year later that I got a phone call from Jeff Garlin, who became an Executive Producer on the film, and he became friendly with John (Maloof. Writer and co-director).

Jeff is a comedian best-known for his work on Curb Your Enthusiasm and other TV shows, but I know him from Chicago. He is also a photography buff. He befriended John and asked if there was anything he could do to help. John said “Well I want to make a documentary” and he started to interview some of the families who knew Vivian.

He had found Phil Donoghue and said “I’ve never made a documentary before so I’m looking to partner with someone who has.” Jeff got in touch with me, partly through Michael Moore who is a mutual friend of ours. Michael said “What about Charlie? He’s been doing this for a long time.” Jeff said “I know Charlie! What a great idea.” So I received a wonderful phone call asking if I would be interested in making a film about Vivian Maier.

I jumped at the chance to be involved. John and I spoke and then got together. Not only did he have over 100,000 photographs, he also had hours and hours of Super 8 footage with audio recording that Vivian had shot. We had Vivian in her own voice and a mountain of material that John had collected from the storage locker that he had helped a family clean out. They were going to throw it all away but he was interested in pulling together Vivian’s entire work.

There were clues about Vivian in the material she left behind so I thought it could be wonderful material for a detective story. We started the process by finding and documenting people’s stories about her – almost like an archaeological dig. We used a visual metaphor of John laying out each envelope on the floor of his studio, shot from above, and systematically creating order out of the chaos that Vivian left behind.

This became a visual metaphor for the whole process – sifting through the things people leave behind in order to make sense of who they are. Telling stories is not a science.

Is that what attracted to you the project? The detective side of the story, putting the pieces together?

CS: The first inkling was that a great story could come from the headline ‘Nanny takes over 100,000 photographs, never shares them and is later found to be a brilliant artist.’

The work was almost lost – like buried treasure. There were intriguing questions about what it is to be an artist. Can you be a private artist? What does it mean to create art that is never seen?

People said Vivian was very private and that she would have hated this and never have allowed it to happen. This created tension in how we made the film. We wrestled with the idea that we were in some way betraying the artist’s wishes. But that struck me as wrong – as presumptuous on the part of the people who were saying that.

Even though people had claims to know her better than we did, the more time John and I spent looking at the work the more we felt this was of historical importance and that Vivian’s work should be seen.

Unlike other artists who expressed a desire to not have their work seen – such as Emily Dickinson, Vivian never expressed a desire to have her work destroyed and didn’t destroy it herself. If you don’t want your work to be seen, you could argue that you don’t save it meticulously at the cost of thousands of dollars throughout a lifetime.

Do you think Vivian would have secretly been pleased? What would she have made of all this attention, from your perspective? Do you think she would have liked it even though she may not have been very good at promoting it?

Yes, I believe that an artist who wants to communicate something about the world and captures something about the world, is thinking beyond themselves.

I don’t buy the idea of an artist creating art for art’s sake, or creating art as therapy. I think it’s reductive and too simple. People – and our lives – are more complicated than that, and ultimately more mundane.

I believe the reason why Vivian didn’t share her work is why a lot of artists don’t share their work. It’s expensive and time-consuming, especially for print-photography.

Personal limitations are felt by many artists, it’s hard to risk rejection and put your work out there. There are the logistics of promoting your work. You don’t just walk into a gallery, get given your own show, and then exhibit in MoMA. Look at John’s track record at getting institutions to take the photos seriously.

The reality is that it’s a little messier than this romantic idea that Vivian was creating art for art’s sake. Or that it was somehow too pure to be seen by an audience.

If having a romantic image of Vivian encourages artists to do their work and soldier on – even though they’re not experiencing fame just as Vivian didn’t – then that’s great.

It’s more heroic to embrace the messiness of life. Vivian’s hair-brained idea to send her work halfway around the world to a tiny village when she was living in New York City and Chicago. Couldn’t she find a decent printer?

So maybe that was a self-defeating idea from the start. I believe it shows that Vivian knew her work was good, she wanted to have it seen. I guess she was making an attempt at it.

I find it implausible that Vivian in her 20s, in the 1950s, and 1960s, decided to start a project, taking tens of thousands of photographs, decade-after-decade for over fifty years, and decided that she was never going to show them to anyone. And in the event of her death, to preserve the photographs. And should anyone find them, to hope they put them back in a storage locker and keep paying the bills or bury them in a landfill. I find it bizarre.

In the film you are talking to the children who are now grown up. She seemed to be a bit of a ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ character. Some of the kids loved her, and some appear to have darker stories. You were there filming the whole thing. Who do you think the real Vivian was?

CS: I think that we can be both – we can be really good to others, and we can have our shortcomings.

We learned that Vivian wasn’t a saint. Who among us is? I don’t mean to apologise for her bad behaviour but these are memories from childhood.

I think memory is a tricky thing. Memories can be exaggerated and warped, and the film is in some ways about how we construct a picture of someone. We don’t get the benefit of 100% certainty about these things. We are informed by our own experience about how we come at things.

The portrait of Vivian that emerges is a result of the stories people tell about her. Sometimes those stories are contradictory. One person says Vivian’s accent is fake, another person says Vivian’s accent is real. We embrace that in the film.

If you could pick some of your favourite photos of hers what would they be? Were there any that really struck you?

CS: [Sighs] At first we thought Vivian was a nanny who happened to take photographs. And out of hundreds of thousands of photographs there would be some good ones in there. Through telling her story we realised this was 180 degrees wrong.

Vivian was a brilliant photographer – a true artist, and she happened to be a nanny. She used it as a cover – or camouflage – so she could pursue her true calling, which was her art.

I’m intrigued that Vivian saw herself as an artist. You can see that in her self-portraits. This is someone who is in full command of the instrument and the medium. She knows exactly what she’s doing with exposure, light, and framing. She plays with the idea of being this mysterious woman.

People described her as being secretive – it’s not so surprising that she was secretive with them, she cultivated an air of mystery. I think there’s a playfulness to all of this.

I think that’s why she called herself a spy.

CS: Exactly – she probably said it. This guy took it very seriously that she was spying for the Russians.

Here she is with this odd accent that some people thought was fake, and it all becomes cloak and dagger. But for Vivian it’s a joke – she was kidding around. But Freud shows our jokes often indicate something deeper so I think in Vivian’s case she was living a double life.

She was this true artist posing as a nanny – and I think you see that in her self-portraits. She wasn’t so private that she never took her own photo. She took many self-portraits. They are like the self-portraits of a Van Gogh or a Rembrandt. Not to compare her to those artists per se, but she saw herself in that way.

She had a real empathy for children and the relationships between families. Given her own broken childhood there was a real yearning to experience those bonds of family life that she didn’t. She is living life as a nanny so she’s really close to families – almost a part of the family – but never truly.

She said to one family “Well, why can’t you look after me?” She wanted to be taken care of and to be part of a family unit. There was a vulnerable side to her too.

CS: Yes, I think that’s right. That’s what makes her life tragic, in a sense.

As one person pointed out, she had the life she wanted. She got to take her pictures. But there is a sense of sadness that she did not get to experience those familial bonds that she saw around her.

Is there anything you would love to ask Vivian if she was still alive? There must be so much more that you unearthed that didn’t make it into the film.

CS: I would like to know if she liked the movie. And would she like having her work seen.

I think any artist would be proud of seeing that what they created had found its audience.

People liked what she’s created. The way she saw the world through her lens is now being seen by millions and inspiring other artists. I think any artist would be gratified by that.

In terms of the way we told the story, you only need to look at Vivian and her articles, and her own journalistic endeavours with her tape recorder. Vivian knew a good story and she liked to chase after stories.

If Vivian came across this headline, I think it’s exactly the kind of article that she would have clipped.

What would you like people to take away from this film?

CS: If you want to be an artist, you make art, that’s what Vivian teaches us. Not this romantic idea that she was creating her work for herself.

What’s heroic about Vivian is she didn’t have acclaim or recognition from others to make her art better or more pure. She continued to do her work, day-after-day, year-after-year, for decades. Without feedback from other artists, and without a gallery or a patron cheering her on.

That is the lesson for any artist, writer or painter. To be an artist means to do the work. We never know who the artists are in society.

Vivian was overlooked, and like so many other people she photographed, she was on the fringes. She didn’t integrate herself into society. She was a spy and had a detached perspective, but she wasn’t an introvert.

Some people described her as a recluse, which I think is incorrect. She was chatty and engaged in the world, informed about politics and what was going on in the art world. She was a combination of outgoing and gregarious, but also couched and temperate, and that’s what allowed her to do her art. She identified with the fringes and I think she was a peripheral character in the world.

She taught us that you never know who the artists are among us; the bus driver or the person taking your ticket stub in the movie house. Maybe they are there because they are secretly making amazing movies themselves.

There are artists here among us making great work. Sadly, most of that work will never be seen.

Vivian is exceptional in more than one way. She’s a great artist and exceptional in that her work was discovered.

I think there are a lot of great artists whose work is in storage lockers and will never be seen.

What is the next stage of the project? Have more photos been exhibited?

CS: John’s work in terms of archiving and curating is continuing. We created a scholarship in Vivian’s name at the School of the Art in Chicago, which is where she went to see movies. She’d go to the movie theatre there and watch arthouse movies, so we created a scholarship, mentoring female students with a preference towards photography. They will be able to attend the school with some of the financial burdens lifted, so her work will continue that way.

I don’t think there will be another Vivian Maier documentary – at least not for us.

The goal was never to shine a light into every dark corner of her life, and the idea was never to create a biopic, or a Wikipedia version of Vivian’s life. Just because there are some things that are interesting about her doesn’t mean that everything is interesting about her.

This really is a story about how this artist’s work was nearly lost, but through all of our incredible good luck, it wasn’t. It’s about the life of an artist and what it takes to be an artist leading a double life, and all the sacrifices Vivian made to do that.

Finding Vivian Maier is still on show at selected cinemas throughout the UK and is available on DVD now