It all started with a poorly recorded Memorex DBS 90. Clear plastic adorned with garish pink, blue and yellow blocks. A lesser cassette, cheap and very much uncheerful, with all the clarity of a neglected fishtank. Yet it was to achieve totemic status in my personal archaeology, bearing the seed of a life’s musical obsessions. My first ever rock tape. On one side, the debut album by The Quireboys, the croaky, ersatz-Faces rootsiness of which kept me briefly entertained then, and makes me want to vomit barbed wire now. On the other, something else entirely.

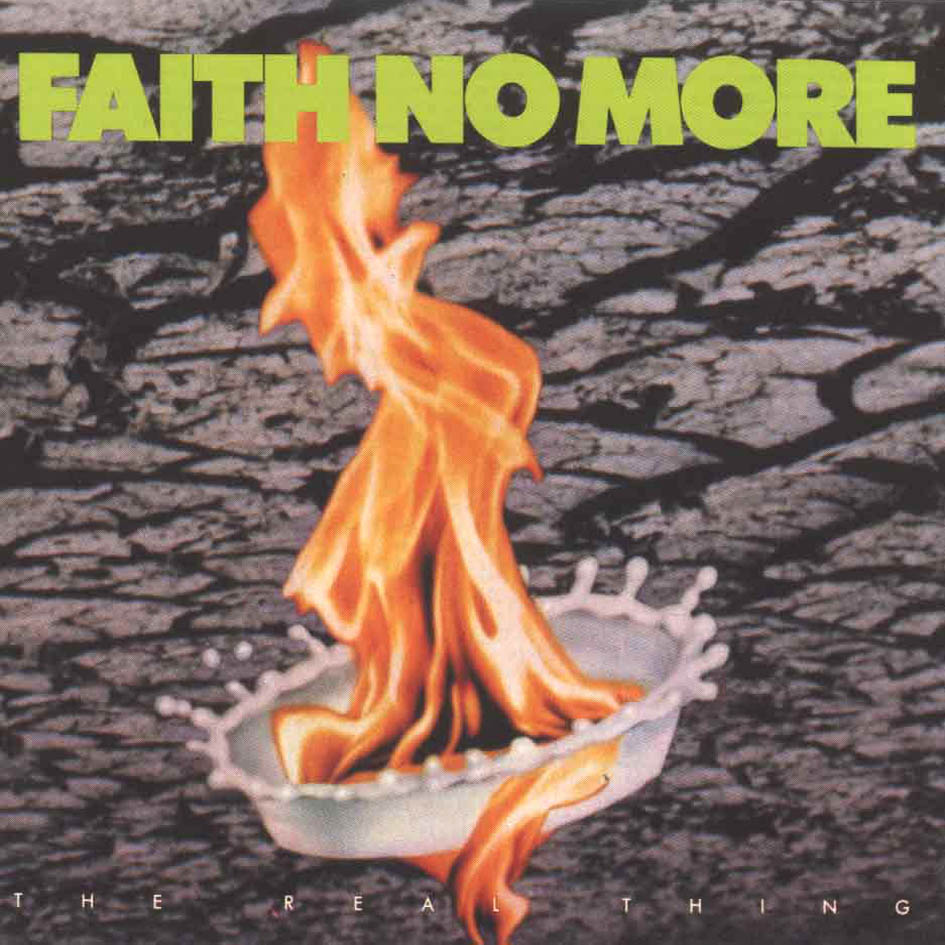

Before The Real Thing, my relationship with music was unformed and unfocused: I’d had brief, vaguely enthusiastic flirtations with Madonna, Sigue Sigue Sputnik, A-Ha, Prince’s Batman soundtrack, the Blues Brothers, but once I discovered metal, everything changed. There was something in the energy and volume and social unacceptability of this music that captivated me then, and still does. At the time, FNM were just one of many metal-or-thereabouts bands to fondle my affections, but they’d have a lasting impact that Skid Row, Pantera and the Electric Love Hogs would not. Not only was TRT my first exposure to Faith No More, it was my gateway drug to rock; to metal. And it would eventually lead, via Mike Patton’s work with Mr Bungle and beyond, to jazz, to world music, to noise, to improvisation, to modern composition, to a universe beyond leather-and-denim tribalism.

To the wider world, and to me, it seemed that Faith No More arrived brand-new and fully formed in 1989. Of course, by the time of The Real Thing’s release, they’d been around almost a decade, in several forms and under a few names. In the early days, they blazed through many vocalists, including Courtney Love, before finally settling on Chuck Mosley – a hugely charismatic but apparently difficult character, whose strengths as an idiosyncratic rapper made up for his technical shortcomings as a melodic singer. Nonetheless, Chuck-era FNM made two superb albums – We Care A Lot (1985) and Introduce Yourself (1987) – but these are the work of a very different band to what would come later. With their collision of funk, punk, metal and rap, FNM’s genre-mashing spirit is very much there, but these are lean, raw, fierce, low-key and grimy records, with dogged, jaggy riffs and massive beats that often pay homage to Killing Joke. But change was coming. After one in-band dust-up too many, Chuck was booted out, and a new singer was sought.

It was guitarist Jim Martin who suggested Mike Patton for the frontman slot, based on a demo tape he’d been sent of Patton’s high-school band Mr Bungle – slightly ironic given that friction between Patton and Martin would eventually provoke the latter’s departure. Patton’s induction into the band was extremely swift. An album’s worth of songs had already been written before he arrived: mostly instrumental, some with words from Chuck. Patton wrote an entire album’s worth of lyrics in 12 days, and the new lineup played its first gig in San Francisco in November 1988. The Real Thing was released the following year – and once MTV picked up ‘Epic’, there was no avoiding Faith No More.

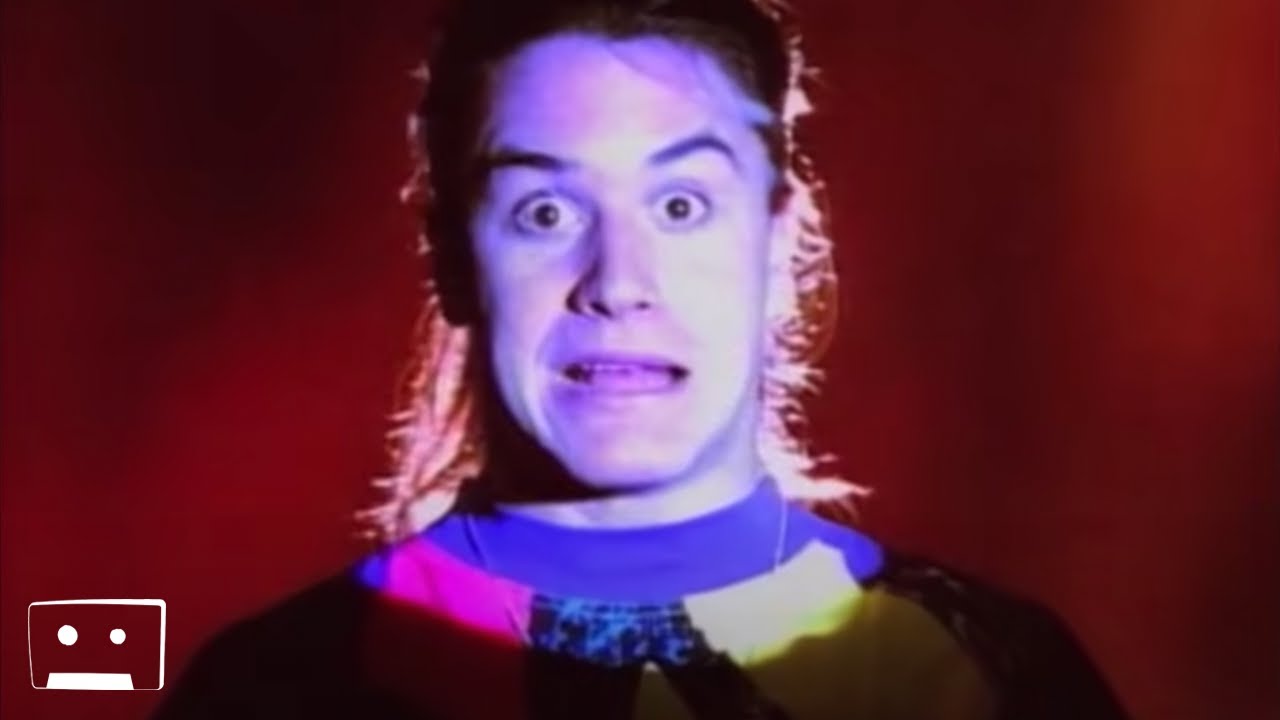

What Patton brought to the band was a youthful enthusiasm, dreamy pin-up looks, a juvenile sense of humour, a lack of narcotic dependency and, crucially, a colossal vocal range – he could sing anything that was asked of him. He was also a naïve kid – a teetotal, small-town California boy, not long out of high school. The overwhelming success of The Real Thing would so disturb this wholesome young man that by the time of its follow-up, Angel Dust, he had become a far more warped and unsettling figure.

So how does this pivotal album in my life story stand up a 30 years later? In all honestly, it’s somewhat wobbly. But ‘From Out Of Nowhere’ remains a massively thrilling statement-of-intent opener, charging straight into a monomaniacal thrash-based riff before launching into its marching band fanfare and skyward chorus. It’s hugely aggressive and confrontational, yet frothy and poptastic at the same time, with bulldozer guitars anchoring Roddy Bottum’s buoyant keyboards. ‘Epic’ is the big one, of course, and remains one of the more unlikely smash-hit singles of all time. In a post-Aerosmith/Run DMC, post-Chili Peppers, post-Beastie Boys world, the melding of rap and rock was no longer startling in itself, but ‘Epic’s structure really singles it out – a combination of lumbering metal dirge, massive beats, heavily percussive rapped verses, obtuse lyrics, frequent soaring refrains that are not so much choruses as fragmented, incongruous interjections poking through from another song entirely, plus two lengthy instrumental sections, one an extended faux-classical outro. As a longtime FNM fan, I have mixed feelings about this song. It’s both tiresomely familiar and grimly inevitable in a live setting, yet inexhaustibly fascinating in the way its chunksome clumsiness glides so effortlessly.

‘Falling To Pieces’ and ‘Underwater Love’ on the other hand, are pop through and through: shiny, day-glo, major-key, slap-bass-led bouncy POP, at once irresistible and fairly irritating. For me, it’s in its murkier corners that The Real Thing shines brightest. Full of black humour and driven by Jim Martin’s vicious riffs, ‘Surprise! You’re Dead’ is a piece of pure, disproportionately nasty thrash metal – and the album’s dark, twisted heart. The presence of this song infects everything else around it. It’s a message scrawled in blood and bile that nothing is safe – there may be pop songs here, but at any moment a flame-breathing hellhound might scorch your face off. It adds a decidedly noxious taint to even the brightest, most melodic moments.

As if to emphasise this, ‘Surprise!’ is followed by the album’s twin quiet-loud epics: ‘Zombie Eaters’ and the title track. The former mashes together delicate, flamenco-infused passages with full-on metal crunch, while Patton’s lyrics depict, in both sweet and unsettling fashion, a baby’s megalomaniacal relationship with its mother. ‘The Real Thing’s lyrical concerns are more abstract and existential, but its sinisterly oppressive modular prog-rap-thrash-metal is impressively constructed, and carries real atmospheric and emotional force, even re-emerging as a chilling opening track at some of FNM’s 21st-century reunion gigs. ‘The Morning After’ is perhaps the least successful moment, struggling to resolve tensions between the band’s pop side and its darker and more musically complex leanings without a massive chorus to use as a crutch. The instrumental ‘Woodpecker From Mars’, however, which seemed like a pointless throwaway 30 years ago, now seems like a highlight – its combination of severe Middle Eastern portents and barely-holding-it-together double-kick-drum clatter-thrash deliriously exciting.

A faithful Black Sabbath cover, a pointedly sardonic hangover from the Mosley era, when Ozzy & co were considered deeply uncool among FNM’s audience, seems unnecessary, even pandering, considering the metalhead audience that would jump on board with this album. However, it does prefigure a fondness for entirely straight-faced covers (most famously, of the Commodores, but also the Bee Gees, GG Allin, Herb Alpert, Deep Purple, Peaches & Herb, etc.) that would be a constant throughout their career. Finally, the gentle, rolling, countrified sway of ‘Edge Of The World’ is notable for its understated nature, unabashed tunefulness, and juxtaposed, pure shit-stirring portrait-of-a-paedophile lyrics.

Patton’s arrival undoubtedly revivified FNM and took them to a mass audience, but for all that he’s clearly The Real Thing’s greatest strength, he’s also its biggest drawback. His vocal delivery throughout the whole record, though impressive, is drenched in blatant affectation – his more natural, rich tone hidden behind a bratty, adenoidal whine that can be hard to listen to now. Looking at live footage from this era, such as the You Fat Bastards VHS, Patton is usually found wearing wacky items of clothing, pulling faces, dancing like a shaved hyena and generally arsing about like a toddler in search of attention from his deadbeat parents. His performances both here and on The Real Thing suggest an extremely young artist wary of the spotlight and unsure how to present himself, taking on myriad visual and vocal disguises as a defence mechanism. From Angel Dust onwards, Patton was an entirely different artist, more at ease with his increasingly jaded and maladjusted self, deliberately shedding his pretty-boy image, exploring the limits of his voice and making a much greater contribution to the records. Yet he recorded the album for which he remains most famous (at least, among civilians) during an embryonic phase that you suspect he’d prefer was forgotten.

The colossal commercial success of ‘Epic’ in particular would prove be something of a burden for FNM – not only earning them a spot on US-centric lists of one-hit wonders, but also saddling them with a rap-rock/funk-metal tag that really only applies to a tiny corner of their oeuvre, but would nonetheless be taken as the basis for an entire genre/way of life by all manner of lumpen, unimaginative dullard imitators. You can no more blame FNM for arseholes such as Limp Bizkit than you can blame The Beatles for Oasis.

Yet, despite its mainstream success, The Real Thing stands as a curious anomaly in FNM’s catalogue – bigger, shinier and catchier than anything that came before, less ambitious and wilfully perverse than most of what would follow, and featuring a half-formed frontman all-but unrecognisable to those familiar with his later work. Its genesis was less than ideally collaborative, but Patton’s subsequent contributions as he became more integrated into the fabric of FNM, especially as he matured as a vocalist and songwriter, would ultimately produce far more satisfying results than almost anything on The Real Thing. For all that this album, bastardised in super-lo-fi onto one side of a bargain-basement C90, had a colossal impact on my younger self, its importance to me now is more historical than musical. It’s a transitional fossil, a necessary stepping-stone between the frazzled griminess of the Chuck era and all the glorious perversity that would follow.