Artists who do a few drawings, a bit of dabbling in video here and a performance piece there, are often lazily described as ‘protean’; a weak excuse to excuse those whose work is diffuse, unfocussed, confused, or an extended and unoriginal parody of an elder and better. But on the evidence of this mid-career retrospective the use of that overused cliché implying a talent for mutability can properly be applied to Tal R.

Here he is in conversation with the critic Terry R. Myers: “I myself have always been interested in changing, moving into different styles, different formats, different materials, in such an obsessive and greedy way that someone should have stopped me, but nobody could and nobody did.” A fact this big show in Denmark makes us thankful for.

The exhibition is entitled ‘Academy of Tal R’, a self-deprecatory and semi-jokey reference to his idiosyncratic approach to teaching and his own kaleidoscopic practice. Each space here is thus visualized as a classroom; so what do we learn?

Primarily that Tal R belongs to that most unfashionable category of artist right now: a ‘pure’ creator, rather than, say, a gnomic setter of puzzles reflecting the cryptic complexities of art theory or a diagnostician of the ills that afflict the planet. The works here are rarely polemical. This is not art about art. His paintings are often short bursts of intense optical energy that fizz on the canvas, visual zaps that do not appear to interrogate much of what has gone on before in art history. Take House of Prince (2000-2004), a room with no less than 191 paintings. We see dots and stripes and squares and wheels and egg shapes and zigzags – many with frames painted on each side in different colours.

Unlike others who work in a similarly maximalist fashion by displaying many works vertically in the old salon style (as with Keith Tyson), Tal R’s intention is not to bamboozle us with his own cleverness but with House of Prince his aim is to simply entertain the occipital cortex. Well aware of the conceptualist critique of retinal art, he toys with the rulebook.

Tal R, Habakuk, 2017, Acrylic and pigment on canvas, 300 x 500 cm, Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin, Galleri Bo Bjerggaard, Victoria Miro, London, Cheim & Read, New York, Photographer: Anders Sune Berg, © Paradis/Tal R – Copenhagen

In one series, for example, he mirrors the literary techniques of the Oulipo group by embracing self-imposed restrictions such as limiting his palette to a mere seven colours. In a work like Black Flower (2005) you find triangles of a lurid confectionery pink carved hard up against earth-brown squares and sun-yellow semicircles. But his colourings are often muted; he’s never too glaring, never too Pop. Imagine a precocious child impersonating Ellsworth Kelly, all naïf grace and charm, and you are getting there.

There is influence of course, albeit kept at arm’s length – Philip Guston’s late cartoony works may have helped inspire the humour of Blocked Door (2000), where a hand, extending from a green wooly jumper, pushes on a door painted chocolate brown and navy blue against a mass of objects, chairs, lamps, potted plants – a laughable situation known to all running low in space at home.

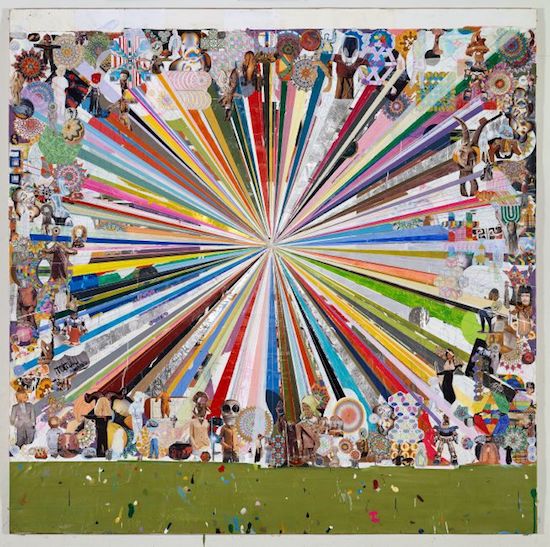

In another room are some of his Adieu Interessant series (2005-2008) – large starburst collages where the predominant colour varies – one version in Seville orange, another in cherry red. Behind the many stripes that radiate like laser beams from the centre point are collaged elements – faces, more bicycle wheels, cut-out shapes from 70’s porno mags, adverts from magazines – a hodgepodge of stuff that Tal R refers to as kolbojnik – a Hebrew word meaning ‘leftovers’. We get an exuberant explosion of life rather than another boring lesson on art and language.

His sculptural room is a childlike wonder world of tinkling things, turning constructions all back lit to project ludic biomorphic shadows on the walls.The shapes look like thread bobbins, phalli, children’s toys, disintegrating fruits. And again here are more of those painted pink candy stripes, his decidedly non-academic equivalents to those of Daniel Buren. Some of these constructions have great titles too such as Bent Onion (2014) or Satie Moon Walking (2014).

Using rabbit-skin glue as a gesso, there follows another sequence of works he paints quickly and thinly. The results have the slightly dull surface of a fresco such as Man from S (2012), where an unidentified flâneur walks the multi-coloured pavements past the striped awnings of a city shop. There is a sense of things disappearing here, a faded quality trying to capture what once was, trying to paint what will soon be gone. Copenhagen is the source of much of Tal R’s urban fascination as with The Prophet from Louise Bridge (2016) where a serene immigrant sits snoozing on a bench above the city’s lakes. One lake in particular (Sortedam) is favoured in a work that obliquely references Edvard Munch’s Moonlight (1895) – in Sortedammen (2013) we see a black moon reflected in a shimmering layer of psychedelic wavelets – a near euphoric inversion of Munch’s dread melancholy. And in his city of dreams, the erotic is never far away, as with the kneeling nude depicted in The Marble (2012).

Lastly there are two new major sets of work – Deaf Institute (2016) and the Habakuk series (2016-2017) both referring to his personal history in a highly allusive manner. Deaf Institute is a set of ninety-nine tall and narrow canvases featuring pictograms and letterings set in a labyrinth in the Hall Gallery of the Louisiana.

The Academy of Tal R, Credit: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, DK, Photo: Anders Sune Bang

In what might be the opening ‘page’ of this novelistic sequence of paintings, we read the ominous words ‘Year Name Departure’. We are reminded that Tal R was born in Israel and his full name is Tal Shlomo Rosenzweig. He is the son of a Czech Holocaust survivor. We see animals – snakes, crabs, and birds, and read references to Egypt and trains. The work is dense and resists simple interpretation but then Tal R is suspicious of easy verbal explanation. His language is the language of paint. And given the unspeakable subject matter, this reluctance to be explicit does not surprise.

The Habakuk series are giant (300x500cm) overlapping strips of canvas, painted with acrylics that feature almost lifesize freight wagons – nine in total – that line the walls outside the maze of Deaf Institute. Such placement is quite deliberate but the scale of the wagon paintings felt constricted here and it would be rewarding (some time in the future one hopes) to see the two sequences of works in separate spaces. Each wagon is painted in different colours; one predominantly blue, another black, another brown, and so on. The word ‘Habakuk’ was made up by his father and it is painted in text on the lower left hand of each wagon.

These troubling works make you suspect that, as with the director of Shoah, Claude Lanzmann, for Tal R explication of the Holocaust is halfway to exculpation. These are monumental paintings and have something of the emotive non-verbal power of late Rothko. Are these a glimpse at what a child being deported from the ghetto saw?

The Academy of Tal R is at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen, until 10 September 2017