The Scottish broadcaster and writer Stuart Cosgrove was once asked what he thought of Pat Kane, famed autodidact and singer in the band Hue and Cry, who was prone to refer to his home library of philosophy that we gather stretches from Adorno to Zizek. Cosgrove said words to the effect that ‘the thing about Pat is that he suffers from a pornographic lust for knowledge reflecting the modesty of his upbringing.’ Not necessarily a bad thing.

Walking around Keith Tyson’s new show it is hard not to wonder if Ulverston-born Tyson is afflicted with what we might call the Kane Syndrome and its symptomatic cry – I’m better than all this parochial palaver.

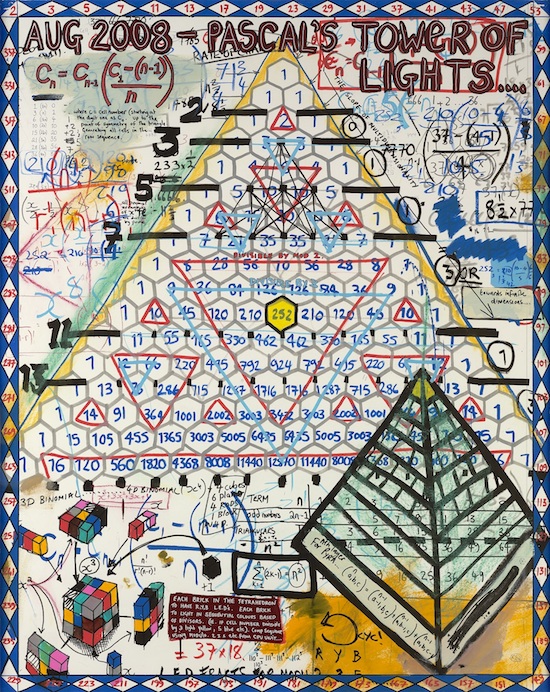

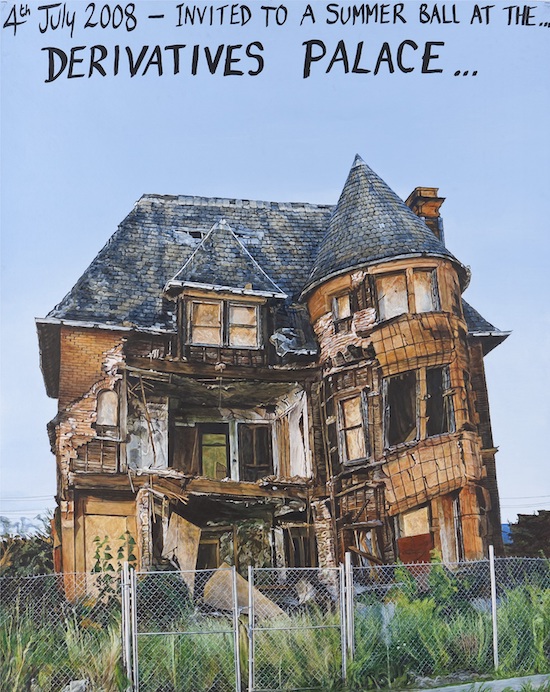

The Jerwood is crammed with 365 of Tyson’s drawings that feature – well, just about everything. The walls are papered with the works in a maximalist Salon style, a deliberately overwhelming move – but what is Tyson trying to say and why does he want to bamboozle us?

There are three rooms in the show each with an overarching theme – the first is an extended meditation on the quiddity of human life on Earth as we know it, Jim. The second majors in micro-worlds, an area stuffed with atomic imagery, quarks, strangeness, charm, and an enormous sculpture of a computer chip board that sits squat in the centre. Lastly we boldly go where no man has gone before – deep space, the cosmos in all its unknown glory. As a patter merchant in one of those old Norman Wisdom films would have it – ‘it’s all happening!’

What is immediately apparent is that you can’t contain all this display in one gulp. The works span decades of thinking and drawing. The energy and labour spent is impressive. The initial response to seeing the illustrations en masse is awe. But all too quickly you sense Tyson flunking Ed Ruscha’s oft-mentioned Huh? Wow! Test. Contrarily you think first – wow, and then… huh?

Tyson is telling us that the world is a big place. Right. The world is a complex place. Right. And we should marvel at that. True. But soon you find yourself asking why does he insist on drawing mathematical formulae in many of these works? There is no sense of true pedagogical intent here. You will not learn more about complex algebra. Tyson’s intentions are demonstrative – he seems to be saying – look how much I know, isn’t my consciousness terrific? And then a suspicion arrives – is he telling us that his brain knows so much more than just about everyone else’s? One recalls the late Anthony Burgess and his endless boastful referencing to his understanding of Finnegans Wake. There’s a rebarbative peacock quality to Tyson’s parade. One cannot imagine it being said that he wears his learning lightly.

Tyson refers to the works as “something between a sketchbook, a drawing, a painting, a journal and a poem”. In that sense there is a parallel with Raymond Pettibon’s works but those have a more powerful political and sexual charge and many a more truer, poetic intent. And putting much of your work together as one giant gesamtkunstwerk is a gamble of a move. Douglas Gordon pulled this trick off with Pretty much every film and video work from 1992 until now, his mass of TV screens, but then he was appropriating many works by others and, in a more modest act, acknowledging their genius.

Tyson has a giant periodic table portrayed here too that he illustrates somewhat in the manner of a school primer kind of way and so using, for example under Polonium, that tragic media image of poor Alexander Litvinenko lying dying in his bed. Predictably we get Madame Curie allied to Radium, a Swan Vesta match under phosphorus, a salt cellar with sodium. All this reminds me of a book my Dad bought for us as kids called The Ultimate Alphabet by Mike Wilks where the challenge was to identify as many of the hundreds of objects beginning with the titular letter in the 26 complex drawings as possible. Fun for a rainy day but soon tiring.

Confronting Tyson’s Turn Back Now it is hard not to be reminded of a more recent example of paternal influence – Viggo Mortensen’s role as intellectual tyrant and father Ben Cash in Matt Ross’ movie Captain Fantastic. There’s a similarly hectoring tone at work here. And just a hint of bullying too – a queasy sense that Tyson expects us to understand what he’s getting at with these formulae or at least and expectation that we go on and try to work out his equations without his help. There is no expert explication on any subject here. There’s a lurking suspicion of obscure dilettantism. I was left confused and muddled with too much on my mind. And there is nothing I can do about it.

Keith Tyson, Turn Back Now, is at the Jerwood Gallery, Hastings, until