That is why we are developing and proclaiming a great new idea that runs through modern life: the idea of mechanical beauty. Whence we exalt the love of machines, of the kind we see kindling in the cheeks of mechanics, scorched and smeared with coal. Have you ever observed them washing the huge, powerful body of their locomotive? Theirs are the attentive, knowing endearments of a lover who is caressing a woman he adores (…) We believe in the possibility of an incalculable number of human transformations, and we declare without a smile that wings are waiting to be awakened within the flesh of man.”

F.T. Marinetti, ‘Multiplied Man and the Reign of the Machine’

At the dawn of the 20th century, developments in technologies and standardisation in the previous century allowed society and the human body to break the confines of nature and its own biological rhythms. The early 20th Century was a time of unprecedented social acceleration, urbanisation, and progress as various groups sought to tear up history and its outdated moves, instead looking forward and embracing the future in all its awesome, terrible glory. In this new contemporary society, everything from art and culture, to transport, industry, architecture, and even human life would undergo a process of regimentation, rationalisation, quantification and abstraction to ensure optimum synergy, efficiency and productivity across the board.

This new society would require a new type of person to be able to operate in complete harmony to their surroundings, in effect becoming Marinetti’s idea of the Multiplied Man. Be it the capitalist model of Taylorist scientific management, or the Russian constructivist movement, this new human would act as a component in an increasingly complex system, where the boundaries between human and machine would become opaque at best. A person who, augmented by various technologies and drugs increase their physical capabilities, would be “designed” as a node for the channelling of industrial discipline and power.

As an artist, Ali Wells, aka Perc, is an electronic musician whose take on techno forms has always concerned itself with interrogating the history and the relationship of the human body with the industrialised world of the 20th Century. Taking a decidedly dystopian bent towards exploring these relationships, his previous albums Wicker and Steel and The Power and the Glory, while ostensibly techno albums, have in their own way cast a light on the utilitarian nature of human deployment of movement, exertion, and power – from the dancefloor, to the office block and the manufacturing assembly line – and how the affects generated by such actions are utilised by abstract forces of capital and politics. It is no surprise that many of the adjectives used to describes Perc’s music are also those that could be used to describe the modernist project of the 20th Century – “Brutalist,” “Uncompromising,” “Industrial,” “Relentless,” “Concrete,” “Masculine.” Subsequently, his music is often seen as continuation of a lineage of music with roots in the post-punk post-industrial milieu, such as Throbbing Gristle, Test Dept., and especially Einstürzende Neubauten, whose tracks from their 1982 album Stahldubversions were reinterpreted and remixed by Perc in 2013.

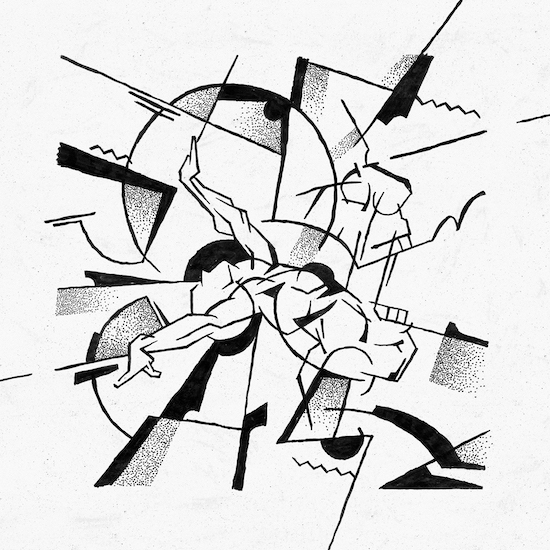

But for his third album, Bitter Music, Perc takes an wider historical view of techno’s relationship between man and machine, tapping a dormant undercurrent all the way back across the 20th Century to a time when cultural forms were mapping out new worlds of speed and energy, a metropolis home to the production of synchronised movement between the masses and the machines that run their lives. Thus, despite the trenchant politics that run through it, Bitter Music comes across more like a paean to a time of unexplored opportunities before the fall, when the idea of the Multiplied Man residing in a gleaming citadel of steel and glass was very much a utopian one. The front cover of Bitter Music, for example, apes the aesthetics of constructivist art of Rodchenko or the abstract expressionism of the Bauhaus movement of Kandinsky and Nagy, where its depiction of geometric order, abstract shading and clean lines, has the human body of the Multiplied Man undergoing a physical metamorphosis, bursting out in numerous directions is an explosion of power, energy, and movement.

In terms of sound and texture, Bitter Music also looks back upon experimental sounds and movements of the 20th Century, such as the use of prepared and atonal piano in ‘Wax Apple’. But from here, Perc goes further in his quest for the capturing of the songs of early machines. In pre-production for the album, Wells travelled to Eve Studios, a residential studio known for collecting and restoring equipment salvaged from the sadly defunct BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Bitter Music is peppered with all manner of electro acoustic recordings and sounds of early electronics, from warped clangs and scrapings of metal on metal, to the click-clack of ticker machines and echoed harmonics from haunted nether zones. Tracks such as ‘Chatter’ and ‘Rat Run’, with their collection of eerie tone electronics, reconstituted sounds from unplacable sources, and corrupted whisperings, are more in line not just with musique concrete pioneers such as Pierre Schaffer and Karlheinz Stockhausen, it also harks back to Perc’s reinterpretation work of UK electronics pioneer FC Judd on the album Interpretations On F.C. Judd.

Perc, however, doesn’t forget that the utopian drive for a mechanical society working at optimal level has long since curdled for many into a pit of exploitation and misery, and it is this dystopian underbelly that is mirrored across Bitter Music. The album’s opening track, ‘Exit’, has a menacing low-level bass throb, as a speech by what sounds like ex-Tory leader David Cameron is overwhelmed by a distorted and bestial machine grunt, as if his supercilious mask has been torn off and the twitching deaths head of capital and brutalisation is laid bare for all to see.

We can also hear in Bitter Music that the worldview of the Multiplied Man is cruel, mechanical, and inhuman, his heart a mere system for distributing energy with no room for kindness or empathy to those who can’t adhere to this paradigm. ‘Unelected’ is as punishing and vindictive as any Perc track out there, with its depiction of the dancefloor-as-foundry, the soundtrack to an Eisenstein factory scene, the drop a cracking scream of metal and noise that reverberates through your body insisting that you push yourself past its limits for the greater good. In ‘I Just Can’t Win’ meanwhile, the disturbing mission creep of a bass/kick combo that while not as visceral in its attack or velocity, is also unyielding and unstoppable in its demands on the body. The poor man sampled in the track, his voice weary with resignation as he tells of his dreary work life is looped repeatedly as his complaints and will are crushed and reduced to a mere assimilated component of the track, the rest discarded as useless. The machine man has no time for your pitiful whining or your inability to yield to the future.

Indeed, the world of Bitter Music and the world of the multiplied man is one that, like traditional gendered notions of the techno dancefloor factory, could be considered hypermasculine – one that breaks with normal relationships of affect and instead worships brute force and chemo-infused industrial greatness – the effective go hard or go home. Women, both on the dancefloors and in the machine age, are considered alien, unwanted, and the Multiplied Man has no time for soppy ideas he feels emanates from women such as “love”, “tenderness”, or “affection.” But this neglects the fact that the age of the machine has also moulded and fashioned women through work, study, and seizing control of their own bodies and emotions, resulting in a transformed multiplied woman open to the possibilities of life and the visceral reactions borne of techno and the mass object.

Perc is more than aware of the independent femininity that exists in electronic music, and this is evident in the brace of tracks that feature UK producer Gazelle Twin. On ‘Spit’ this manifests itself as a red lining howl of female vocal distortion, a spewing of visceral energy accompanied by a punishing kick drum. But on ‘Look What Your Love Has Done To Me’ she deploys a different register of emotion: her delivery of singular words such as “Trust… Push… Sloooow… Fast…Night… Work… Drag… Force” have a level of intensity and affect that is removed from standard raunch or eroticism, instead coming across with a more noted jouissance in the physical demands of the track’s anvil kick fashioning metal shards that are stuck onto and in our fragile flesh. Bitter Music might be brutal, unforgiving and, at times, painful, but it forces to acknowledge that deep down we might actually like the Tetsuo-like transformations to mind and body we are being subjected to.

Today, the age of the discipline and the machine has now been upgraded and superseded by the age of the control and the network. The boundaries of the human body itself and its need to be situated in a point in time and space are becoming ruptured as our sites for experience and feeling are now digitised, multiplied and circulated online at almost infinitesimal layers of discretisation executed at breakneck speeds. The Multiplied Man, with his fixation on the foundry, the motor, and circuitries of the flesh seems like a quaint notion in a time of robotic automation as the need for an actual body becomes tenuous and less essential. Cultural forms, from music to drugs, are now more for the mind and its capacities rather than for the body and its limits. With an eye on the disused factories and the discarded bodies of its workers Bitter Music, despite its harsh nature, has an almost faint whiff of nostalgia for a time and a worldview that we knew and thought we understood. Our views of the future are now much grander and more terrifying.