When a poet’s tale is told in the medium of film, you can always expect an extra dose of sex, madness or romance will be added to the equation. This is because poetry, by and large, is painfully straightforward: person sits in room, alone, and writes and re-writes and screws up and starts again. Weeks may pass and all they’ll have to show for it are a few pages of messy manuscript. Like mathematics or theoretical physics, the work goes on in the mind as much as on paper, but whilst a mathematician may work towards an envisaged solution: it’s much harder to quantify success in poetic composition. Telling a poet’s story is difficult because – unless you count the sale of a few hundred volumes – there’s rarely a moment of triumph around which the story can be framed.

Writing is a headlong, inherently unsexy pursuit and bringing a poet’s life and work to the big screen is an unenviable task even though film possesses its own poetic grammar. Whether that’s the lyricism of its photography or the tempo and rhythm of its editing: film poetry is readily conceived. In his 1970 book Expanded Cinema, Gene Youngblood argued that the time had come to “liberate [cinema] from theatre and literature” and embrace what he termed ‘synaesthetic cinema’: a non-linear, non-dramatic approach to motion picture that could help to make sense of our “post-industrial, post-literate, man-made environment with its multidimensional simulsensory network of information sources.” It could allow an image to be understood as a poem in its own right without any support from a narrative or script. Frank Ocean’s recent experimental visual album Endless – in which he, very slowly, constructed some stairs – suggests, at the very least, that the sort of avant garde Youngblood was describing can still occasionally be approached by popular entertainers whether or not Ocean’s project was serious in intent.

For the most part, however, those of us who still crave the sort of cinematic excitement that Youngblood looked down upon as cheap emotional exploitation will find films about poets typically caught between those two dimensions: trapped between earthy drama and ethereal delight. Without the strong bones of a story from which to hang the silky stuff of verse, trying to make a poet’s life come to life is distinctly tricky. Even the best film-makers will court the risk of delivering a film that only half satisfies either instinct, and appeals more to the tranquilized than the die-hard fan.

Jim Jarmusch’s recent film Paterson was remarkable partly because it avoided either problem. It was neither dull nor sexed up, but it was aided considerably in its success by focusing on a fictional poet. The quiet routine of Paterson’s life was made into a virtue, he seems to possess a zen-like happiness throughout, and because his writing was occasional in nature (jotted down at a good moment, with minimal revision) it allowed a convenient, if perhaps contrived, view of how a sensitive character might casually compose without too much care. If a feature length film were to be made about Philip Larkin – who could take the best part of a decade to write a slim volume of poems – it might not make for such a gratifying watch.

Fans of Emily Dickinson, however, whose life was hardly a rollercoaster of biopic-baiting events, will be delighted to discover that she has now been honoured with the big screen treatment courtesy of Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion. The film works extraordinarily well as an exploration of her personality and the atmosphere of her poetry. Just like Paterson, it manages to keep your attention for two hours without pulling any gimcrack narrative tricks beyond the occasional (inevitable) wheeling out of Dickinson’s most famous verse for a little show pony action. It makes the psychology of sadness and isolation watchable in its own right. That’s quite an achievement, but even more so when you consider that films about wild and drunken poets can often do worse with greater riches of biographical excitement.

Dylan Thomas, for instance, seems like a perfect candidate for a saucy bio. His poetry is as rich in tone and imagery as his fabulous reading voice and he loved drink like St. Paul loved the church. (If only fate had allowed it, one imagines that he and Oliver Reed would have made excellent drinking buddies). Yet, for all that, an attempt to make his rakehell ways shine in John Maybury’s The Edge of Love (2008) doesn’t work. The menage a trois drama, in which Thomas (played by Matthew Rhys) reads his now-famous (but not then) compositions in bed to his wife Caitlin (Sienna Miller), tries to add an extra chocolatey smooth element of sex to a poetic corpus which is deeply lyrical but not quite so steamy. (Tom Hollander’s portrayal of Thomas, in Aisling Walsh’s BBC production A Poet in New York, by contrast, took a more direct approach – revelling in the sweating, puking, corpulent illness of the poet seeking his death in drink.)

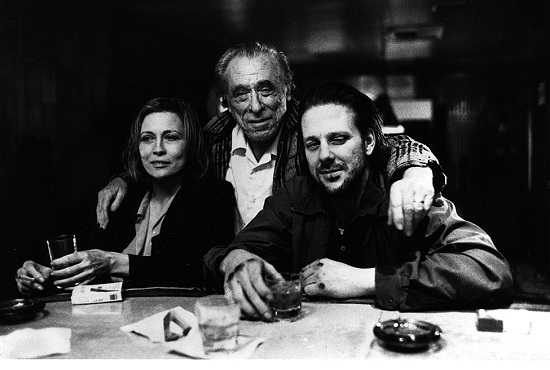

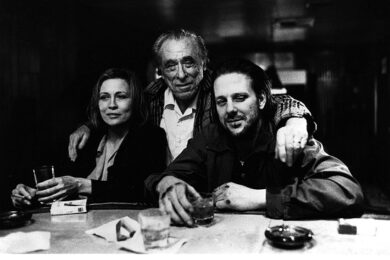

Compare this with Barfly (1987), in which equally well-known booze fancier Charles Bukowski (or, to be precise, his cypher Henry Chinaski) is played by Mickey Rourke and it’s easy to see the difference. It helps that Barfly was written by Bukowski himself – suffusing the script with his style of gruff wit – but it’s also important that the grubby atmosphere of his work is brought alive through the queasy greys, greens and beer-yellow light of the photography. Nothing is added to Bukowski’s world. The excitement of the film is everything that his writing was with his lunatic escapades in slum apartments and run-down neighbourhoods. There is one scene in the film which indulges the poet-at-their-desk trope, common to most films about writers – where Chinaski types at a table and his work is read in voice-over. It is the only moment in the film, however, where writing begins to seem like anything but a sideline to the important business of getting seriously plastered as often as possible. And there’s nothing pretty about it. Rourke’s lank hair and stained boxers do not exude a rakish glamour. Like Bukowski’s poetry, these details are austere but eloquent – speaking truthfully about the world, its griminess included. Its griminess especially.

Perhaps the bottom line for success in bringing a poet into the cinema is that you can’t make something happen to the poet’s work that didn’t happen. The attempt to generate excitement from elsewhere will likely fall flat – confounded by the seriousness of the poetry itself, perhaps. To really make it work requires a film-maker to try and capture the atmosphere of their poetry in a way that is ‘synaesthetic’, to use Youngblood’s term: exploring the lexical landscape of a poem within the space of the film itself. In the case of A Quiet Passion, Dickinson’s life was contained in a number of ways. Geographically, by the fact of her hardly leaving Amherst where she was born. Emotionally, due to her solitary nature and the fact she compartmentalized much of her social life within written correspondence. She was also insulated by the quiet of night in which she did much of her writing. All this is reflected in her poems, to some extent. At once clipped and contained, but – thanks to her beloved em dashes – always pointing out to the blank exterior of the white page; the whiteness or blankness being a stand-in for death, perhaps, or simply a space beyond the fact of her writing and her life. A Quiet Passion captures that atmosphere of being shut-off with its housebound interior filming (Dickinson is shown staring out of a window, in the middle of the day, almost as often as she is seen outdoors). This gives the film the same captive intensity of her poems.

In terms of tone, this is similar to Tom & Viv (1994), Brian Gilbert’s period drama about T.S. Eliot and his wife Vivienne Haigh-Wood Eliot. The film’s many interior scenes offer something of Eliot’s tightly buttoned-up, despairing worldview: actors are made to look small in the large spaces of stately homes or uncomfortably boxed in amongst the confines of rooms made small by being covered in books and papers. Vivienne’s bouts of mental illness detonate that stuffiness – her manic behaviour allows dance, sex and an uncareful clatter of words into a world where cool British composure should be in control. Since the film concerns their relationship as much as his poetry, it is allowed the luxury of being uninterested in his writing. (In one memorable scene, Viv walks out of the house as Tom is giving a lecture to his Bloomsbury crowd to go have tea with a friend; as a viewer, you almost share her relief that you won’t have to listen to his monotonous speaking voice droning on and on). Her poor mental health is not added to the film to make sense of Eliot’s poetry or to make their story more interesting: it simply is the story, for better or worse. The actual poetry is something of a sidebar in the film, and yet it provides an important context to reading his work. It manages to say something significant about Eliot’s poetry without really examining the poetry itself.

This is the opposite approach, in many ways, to Howl (2010) – a film about Allen Ginsberg’s poem of the same name which does everything it can to make the content of the poem manifest on the screen. It uses hot jazz, fast edits, switches between over-saturated colour and black and white, and jumps in the timeline (as well as excursions into surreal animation) to portray the sensual derangement that the Beats wanted to capture on the page. It does this whilst also providing vital hypertext to the poem itself – it is close to academic in its insight and detail, but without being staid or dull, going through select lines and offering specific glosses on their reference to certain historical figures. Howl is a performance piece, offering a reading of the poem alongside the history of its composition. It’s a flawless look into the life of a written piece of work, where neither its performance nor its composition are interrupted by the outside world: the phone call that disrupts the poet’s flow, the fruitless hours wasted over lines which fail to make the final cut, the restless audience who can’t quite pay attention when you, the poet, feel they should.

In Peter Whitehead’s Wholly Communion (1965), a documentary about the International Poetry Incarnation (an event held at the Royal Albert Hall ), a moment is captured for posterity involving the poet Harry Fainlight reading from his poem ‘The Spider’. Seemingly unmoved by Fainlight’s poetry, the Dutch writer Simon Vinkenoog, with eyes like saucers courtesy of his mescalin high, heckles the poet in a most groovy fashion. He interrupts Fainlight’s recital by chanting “Love, love” to the general applause of the room. Fainlight, gobsmacked, tries to keep reading but can’t quite suffer the indignity. He has to be comforted by the writer Alexander Trocchi before he can be convinced to continue.

It’s a reminder that, no matter how clean poetry seems, it can be a messy business. It invades our lives, as readers, in strange ways – and the same is true of the poet’s experience. The E.E. Cumming’s poem that obsesses Michael Caine in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) is perhaps no different, in its tormenting effect, to the acoustic hallucinations with which the poet John Clare felt persecuted during his escape from High Beach Asylum. (A journey documented in another poetry biopic, By Our Selves – a daring film by Andrew Kötting that rivals Howl in its desire for an immersive look into a poet’s life). Films about poets are a tricky endeavour because a poet’s mania for language is not cinematic in the way we hope for if we’re hoping to sit back and relax. It’s easy to turn John Keats into a sickly sweet lover boy – as in Jane Campion’s admirable, but overly sentimental Bright Star (2009) – or make Dante Gabriel Rossetti into a manic, almost cartoonish figure, as in Ken Russell’s Dante’s Inferno (1967). It’s much harder to offer a faithful view of a poet’s life and work without gilding the lily with too much madness or too much sex. The films that fail come across like sporadic voice-over recitals wrapped up in something a bit juicier than could ever really be true to life. The films that work give you the poet and the poetry without flagging your attention to a distinction between the two. They make the life and the writing gel without having to earmark the text for further reading.

Poetry at the Movies: Best of, Worst of.

The Best

Wholly Communion Peter Whitehead

If you fancy a properly poetic cinema experience, why not watch a documentary about a poetry recital? The International Poetry Incarnation was organised almost on a whim after a reading of Allen Ginsberg’s in a bookstore proved surprisingly popular. Wholly Communion captures the atmosphere of a few thousand people gathered together to admire their favourite Beat writers, or – in the case of the Fainlight incident – provoke them whilst taking mescalin.

London Patrick Keiller

Patrick Keiller is known for his film essays which use long, sometimes entirely static shots to explore urban landscapes. Their images of deserted locations have an elegiac quality, taking on a poetic register that is purely visual, but this section of cult favourite London is also accompanied by Paul Scofield’s wonderful narration.

Church Going Larkin And Benjamin

It’s pretty rare for a poet to get behind the camera when someone wants to make a film about their work, rarer still for them to star in the film. This short clip features Philip Larkin acting out his poem ‘Church Going’, before jetting off back home to do some urgent filing in his library dungeon of jazz records and vintage pornography.

The Worst

Four Weddings And A Funeral

Poetry, according to one perspective, can only work if it has the potential to shock us with invention and make familiar feelings or experiences come alive again. If certain metaphors or lines of poetry become overfamiliar they become deadened with use. So thank you Richard Curtis, for taking a poem already suffering from over-circulation and making sure to fully finish the job.

Interstellar

The single laziest move of a screenwriter involves taking a famous poem and using it to try and reflect a little glory on their script. This isn’t poetry so much as a cultural laser beam designed to zap its audience into thinking Interstellar is an instant classic and not a cash-guzzling waste of three hours. Like that guy you know who likes to try and pass off other people’s jokes as his own – they don’t even bother to attribute the poem to Dylan Thomas.

A Quiet Passion is in cinemas today