As predicted last month, Safari Festival was excellent. Although small, it was highly concentrated and still incredibly easy to burn through cash at a faster-than-expected rate. There were standout selections from Breakdown Press, Decadence, Fantagraphics and Simon Moreton/Retrofit Comics plus plenty of smaller stands, and many chances to get comics signed and drawn in.

This month we welcome a new writer, Kelly Kanayama, who reviews Ladykiller Vol 2 below.

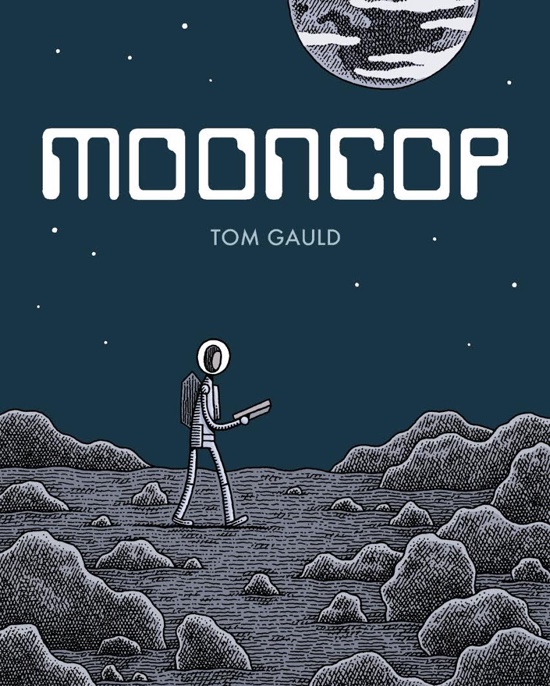

Tom Gauld – Mooncop

(Drawn & Quarterly)

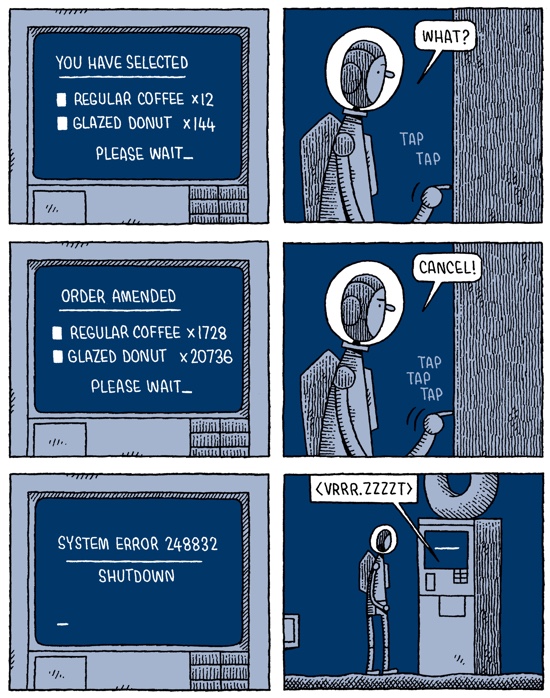

A new Tom Gauld book is always a treat, and this is no exception. With his brilliant Guardian and New Scientist gag cartoons appearing weekly, it’s easy to forget his talents extend to longer form works. This compact and elegant two colour hardback is up to D&Q’s usual quality standards, and the contents are up to Gauld’s. Mooncop is a quietly melancholic tale of a police officer posted to the moon. The moon has been colonised but the experiment appears to have been judged a failure, and most people have left. This means there’s very little for a cop to do, although great for his stats; no crimes means no unsolved crimes. He spends his days driving about, and finds that nearly everybody he encounters is leaving. Gauld is a very economical storyteller – you won’t find any exposition or florid prose here. A series of static shots of buildings show very few lit windows, perfectly conveying the atmosphere of the twilight of this community, and showing small signs of decay and abandonment.

One of the themes that emerges is the way we are all at the mercy of faceless bureaucracy that we have no control over. For example, one day he returns to his apartment block to find that empty units have been removed, and his has moved from the eighth floor to the fourth, transforming his view and his mood for the worse. Everywhere he goes he finds an unwelcome change of one sort or another has been imposed on him, a feeling it’s very easy to relate to. The donut and coffee vending machine he frequents daily is removed, supposedly to be replaced with a cafe unit. However, Gauld is keen to remind us that not all change is bad even if it makes little sense at first.

If the book is in part about how we have little control over many aspects of our life, it’s also about the importance of connection to other people, and how this is what can make life meaningful. Although the book is melancholic it is also very funny at times, with Gauld’s dry understated sense of humour. His distinctive, side view art is masterfully deployed in the service of his narrative. This is an undeniably superb book. Pete Redrup

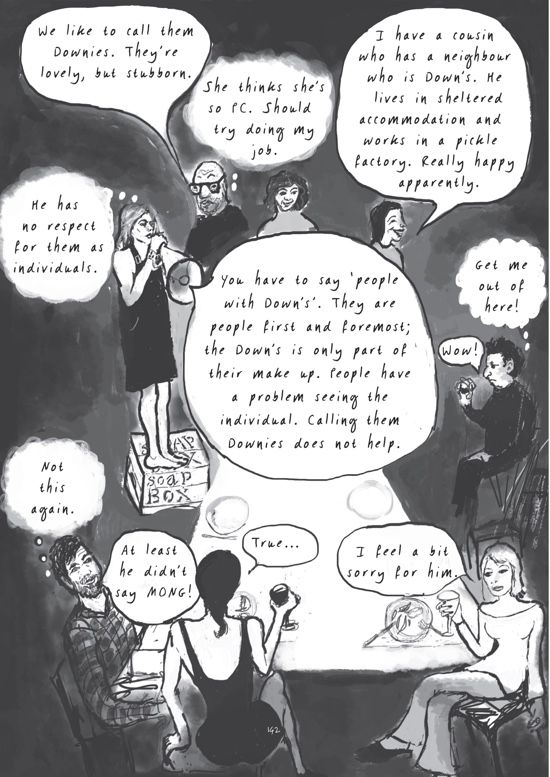

Henny Beaumont – Hole In The Heart

(Myriad Editions)

Myriad Editions have a knack of publishing eye opening, emotionally devastating work that never neglects capturing readers’ interest whilst having an important message. Henry Beaumont’s debut graphic work Hole In The Heart is the latest in this tradition, a memoir of her experiences of motherhood. In 2001 she had her third child, Beth, and shortly after birth was told her daughter had Down’s Syndrome. This book is her account of the next 15 years.

One of the first things that strikes you when reading this is that the art is exceptionally accomplished. Beaumont is a portrait artist, and it shows, for example through the faces that are much more detailed and realistic than one typically finds in comics. However, being able to paint is not necessarily enough to create a compelling work, and the art here has much more than verisimilitude to offer. It’s especially effective at showing how utterly tormented the parents were, and how they felt in the face of normal life going on around them for other people. The book is full of tears, and these are represented in various visually powerful ways, for example filling up the page, or puddling and whirlpooling on the floor. One visual metaphor I found particularly striking was when Beth is excluded from sports day at school for her behaviour, and Beaumont was belittled by the school staff. Riding home her bike changes to a child’s bike, and one suited to rough terrain. The book is full of these little touches that demonstrate hugely impressive creativity for anybody, let alone in a debut work.

Hole In The Heart does not paint a brilliant picture of the medical staff at the time of birth and diagnosis. For the professionals, this is part of the working day; for the parents, it’s their world turned upside down. This theme returns again and again, for example with their experiences of education right until Beth attends a special secondary school, rather than the mainstream places she had been in until that point. The book repeatedly shows the job of being a parent, the desire to give your children the best you can, and being fiercely protective. It’s compellingly honest, particularly in the early stages as Beaumont confronts her own prejudices about disability. She and her husband were particularly worried about how Beth’s needs would affect their other children, but they were utterly accepting of their new sibling in a totally instinctive way. There are numerous examples of this, such as when Beaumont was still struggling to come to terms with the changes to her family, taking photos of her daughters and excluding Beth from the pictures, while the girls did everything they could to get her in the frame.

With a powerful ending, we’re left in awe of the skilful storytelling, the brilliant art and the author’s honesty, and left to reflect on our own prejudices as we see Beaumont overcome her own. This is a brave and brilliant book, highly recommended. Pete Redrup

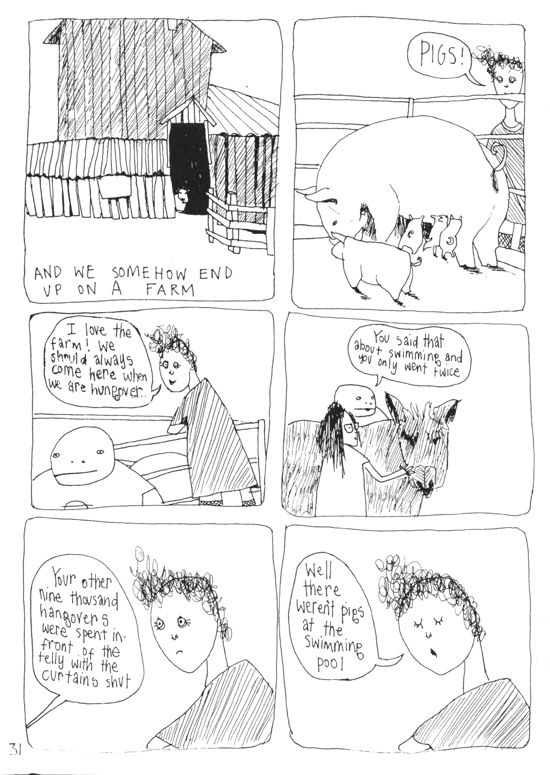

Danny Noble – Hangover Farm & Ollie & Alan’s Big Move

(Self published)

Hangover Farm is hardly a recent work, dating from 2004, but it shows that Noble’s storytelling talents have been around a while. Hardcore Noble collectors will no doubt want to hunt down a first edition photocopy from her university days, expense be damned, but for those of more modest means this is available on her webstore. If you are her mother, this is a work of fiction. For the rest of us, it is broadly autobiographical, although the level of embellishment is not clear. Were I one of her friends featured in it, particularly Tom, I would also be ensuring that my mother did not get hold of a copy, or pleading the case for heavy embellishment.

This is a series of tales of comic ineptitude at life. The contents page led me to assume it was a collection of unconnected short stories but they are chapters and there is an overall narrative arc. Any reader who has encountered Noble’s work elsewhere will know she is an extremely funny artist and storyteller. The imprecise panels are filled with deceptively simple, scratchy images that work superbly, with faces that perfectly evoke the shame, embarrassment and sometimes horror that typically emerges by the final panel of each chapter. Meanwhile, the pacing of the narrative is always flawless. An early chapter, Bruno And The Coffee hilariously recounts how an attempt to befriend a withdrawn member of her art class resulted in a beverage related mishap and the destruction of months of his work. It’s always a total pleasure to read autobiographical work that is this funny – Noble manages to portray herself as a sympathetic, likeable character whilst causing mayhem everywhere she goes, no mean feat. I loved this book.

Ollie & Alan’s Big Move is her most recent publication, and the second based on the permanently naked characters of Oliver Reed and Alan Bates, who have apparently been unable to dress themselves since meeting on the set of Women In Love. Again, the reader is left pondering just how much of this is autobiographical (does Noble have a painting bandanna? Did she buy 70 cases of port to get the boxes she needed for moving?). This book is about their attempt to move house, and the narrative structure imposed by this simple idea works better than Was It…Too Much For You, the first appearance of this pair in her work. Production values are much higher here than Hangover Farm, with perfect binding as opposed to saddle stitching, but the contents have the same unique style. Again, this is a deeply funny book, most pages featuring three panels with deftly paced punchlines. Noble is a highly entertaining cartoonist, and either or both of these very reasonably priced volumes are well worth acquiring. Pete Redrup

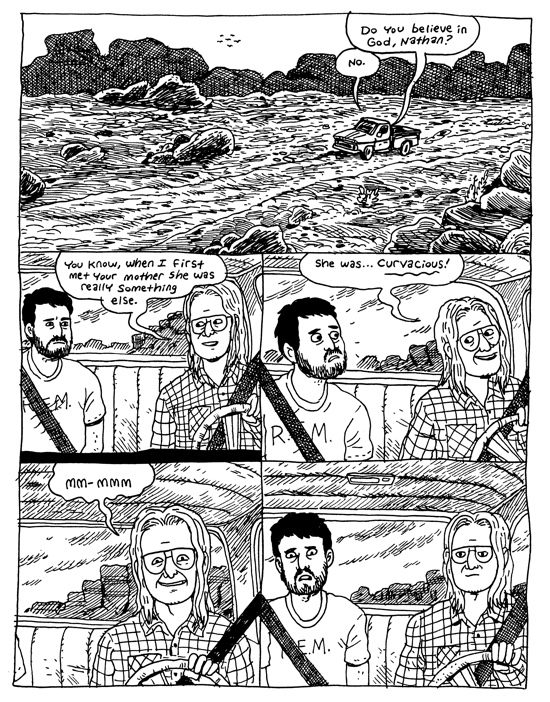

Noah Van Sciver – Disquiet

(Fantagraphics)

Disquiet is the latest collection of short pieces by Noah Van Sciver, following on from 2014’s Youth Is Wasted. Fantagraphics have given this the luxury treatment, so it’s a cloth bound hardback with an embossed cover, and it’s nice to see his work thusly formatted, compared to the small softcovers of his last two books for them. Inside we find a collection of short stories of varying length, several in full colour. Some of these are from his Blammo series, which is not easy to come by in the UK, and a few are from other publications.

Van Sciver’s work is immediately recognisable due to the way he draws his characters, and the characters he chooses to draw. The drama in his work often comes from writing about out-of-luck protagonists, and this collection is no exception. They often look on edge, distrustful of those around them, waiting for life to deal the next blow. We see them scraping by, renting rooms, revisiting the past or trying to leave for a new future. They do this on intricate, detailed pages with little negative space, making the most of his ability to draw interesting backgrounds. The first longer story, The Lizard Laughed, is an excellent example of this, and a really strong piece overall. An estranged son visits his hippy father in New Mexico to get some answers about why the father walked out. They go for a hike, and the exterior scenes in particular are very effective. Another of Van Sciver’s trademarks is the historical comic, and there’s a long colour piece about the abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy. Finally, there are some of his more fantastical stories, like The Cow’s Head and Punks V. Lizards, in which a gang of punks battle giant lizards on the streets. As well as the stories, there are a series of pages of silhouetted heads with illustrations within, starting with the cover. These are superb, and really add to the overall impact of the book.

Reading a collection like this, it’s clear that Van Sciver is both talented and hardworking – in the two years since his last collection was published he’s brought out two graphic novels, Saint Cole and Fante Bukowski (reviewed here and here), will soon have a new historical book out, a biography of Johnny Appleseed, and is some way through another Fante Bukowski story. This is a great chance to catch up on some of his shorter work in a particularly lovely edition. Pete Redrup

John Porcellino – King Cat 76

(Self published)

John Porcellino is back with the 76th edition of his King Cat series. This is very different to #75, a longer edition which focused exclusively on Maisie Kukoc, Porcellino’s late cat. This has no overarching narrative, and is more like a zine than a comic in that it has several short pieces with no narrative connection, a top 40 (containing a number of elements not equal to 40) of things of interest stretching from music to restaurants, and a lot of letters. In short, back to business as usual.

If you’ve come from #75, The Hospital Suite, or another more tightly themed book, this might seem a little strange. However, in the context of King Cat as Porcellino’s life’s work, this makes much more sense. A series like this (I’m not sure there is another series quite like this, although Simon Moreton’s work shows some similarities of approach, if not yet length) reflects not just the artist’s life in terms of events but also connections, moods, snapshots of experience and just images that they’ve chosen to capture and share. It’s all about the overall texture. It reminds me of the way that Frank Zappa produced a staggering quantity of media – an unbelievable range of music, plus film and video and much more – and saw it all as part of one thing, his Project/Object. A rock band singing about the yellow snow was just the same to him as the London Symphony Orchestra performing his classical compositions, all part of his life’s work. King Cat is the same, whatever Porcellino chooses to include. Don’t buy this if all you want is another King Cat 75. Buy this if you want to experience a unique, intimate series of comics that is as much about texture as it is about events. Often bracingly honest, Porcellino reveals himself deeply in his work. Life isn’t always momentous events, however, but in the way he shows this, he still leaves us feeling like we know a little more about him. That people really connect with his work is apparent from the letters pages in his comics, and this is in part due to the sense of intimacy he creates.

King Cat is not widely distributed in the UK. Page 45 in Nottingham carry it, or you can order copies direct from Spit and a Half, Porcellino’s distribution website (which is a great place to pick up a ton of things that don’t make it across the Atlantic). I’d recommend getting this, and a copy of #75, which whilst atypical for his work is typically brilliant. Pete Redrup

Pascal Girard – Nicolas

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Nicolas was given a limited release in 2008, and is now being reissued by Drawn & Quarterly in an updated hardback edition. Recounting the author’s childhood experience of the death of his younger brother, it was written very early in his career as a cartoonist. The small, slim volume is quite minimalist in terms of what’s on the page, but at the same time is emotionally rich and complex. In his introduction, Girard notes that he was inspired by Jeffrey Brown’s AEIOU and wanted to create something in a similar narrative style. Turning to his own experiences and working fast, he produced Nicolas. For a relatively inexperienced cartoonist, he shows considerable storytelling skill, producing a sparse account in a series of snapshots. Not only does this mean a greater degree of reader engagement as we are forced to fill in the gaps ourselves, but it does a deft job of conveying the way that a tragedy like this does not have one simple, easy to categorise effect, but produces a varied range of responses at different times. It also manages to show the way children feel things differently to adults, more id than super-ego.

This edition includes an afterword, which makes up about a quarter of the book. Girard’s art is much more refined, as one might expect. It shows how the childhood events affected him as an adult, and focuses quite heavily on his developing relationship with another younger brother born after Nicolas’ death, with whom he was not close. Girard clearly attributes the anxiety disorder he experiences as an adult to his bereavement, and it’s interesting to see how he pieces this together. Nicolas is an honest, moving piece of work, very much enhanced by the new content. Pete Redrup

Alec Worley & Pye Parr – Realm Of The Damned: Tenebris Deos

(Werewolf Press)

The universe of this highly gory graphic novel, written by Alec Worley and drawn by Pye Parr, has recently expanded to include a soundtrack created by a Gorillaz-style virtual band, the Sons Of Balaur. There’s also a full-length anime version, voiced by heavy metal celebs, to be launched at the Prince Charles Cinema in London on 20 October. All this activity is justifiable: the source novel is beautifully drawn and ambitiously plotted, despite the odd derivative plot point.

Realm Of The Damned: Tenebris Deos is set in a massively unpleasant future, resembling modern Britain in decay, ruled by vampires, werewolves and other bloodthirsty types. The charismatic anti-hero is a vampire hunter called Alberic Van Helsing, who is blackmailed into collaborating with his foes when an ancient demon, Balaur, is reanimated by a black metal band, his disciples. Balaur, a truly nasty piece of work, chews his way through a series of supernatural beings on his way to universal domination, facing up to Van Helsing at the last.

You can’t help warming to Van Helsing, because he faces familiar struggles despite his miserable existence. He’s addicted to vampire blood, which renews his youth every time he injects it, and he’s a devout Christian, fighting to retain his belief in the existence of a benevolent God despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Sure, parts of his character are familiar from Hellboy and Hellblazer, not to mention a hundred cheesy Hollywood adaptations from Underworld to Blade, but he’s twisted enough to retain your attention.

He’s balanced out by a terrific set of supporting characters, from Balaur’s undead sister Athena and a French werewolf overlord to an Egyptian mummy queen. The writers have essentially set up a compelling fantasy universe, inked it in monochrome plus blood red and a small palette of primary colours, infested it with grade-A violence, F- and C-bombs and some relatively tasteful nudity, and let it loose. Highly enjoyable. Joel McIver

Isabel Greenberg – The One Hundred Nights of Hero

(Jonathan Cape)

In his review of Robert Altman’s Popeye, Roger Ebert writes, “Altman’s musical comedy takes one of the most artificial and limiting of art forms – the comic strip – and raises it to the level of high comedy.” I think Calvin and Hobbes alone debunks Ebert’s remark, and I don’t mean to pick apart a thirty-five-year-old film review from a man that has lauded dozens of comic-based films, but his comment seems to imply that the comic medium is unable to attain the level of ‘high’ art, a remark that I think is out of date in the face of The One Hundred Nights of Hero by Isabel Greenberg.

The book is a follow up to Greenberg’s previous graphic novel, The Encyclopedia of Early Earth, a comic that I thought was an impressive debut, but still a little immature. Her latest book shows how far Greenberg has come as a creator in only a few short years. Her love for storytelling and folklore is pushed to new levels, and it is a dizzying delight to experience the stories within stories within stories. The book begins as many of this kind do with God granting humans knowledge. The gods can then be worshipped, but an unexpected side effect occurs. The humans learn to love. This begins the central conflict of the book, a wager between two men, Manfred and Jerome, arguing over the fidelity of their women. A dangerous test begins when Jerome leaves his wife, Cherry, to Manfred for one hundred days, promising Manfred that she will not succumb to his seductions. This trial not only affects Cherry, but also her true love and maid, Hero. The two women know that if Manfred cannot win the contest fairly, he will cheat and take what he wants by force, so Cherry and Hero distract him with stories.

Like Manfred, we become lost in their stories. Tales of rival sisters, magic harps, moon mistresses, and mirror worlds keep us wanting for more, and as the story climaxes we discover that what seems like many stories is actually one giant story. Influenced by classic mythology, Greenberg fills her tales with violence and oppression, but delivers the stories with lighthearted artwork and prose so that we never feel like there is a message being forced, but instead many ideas to be discovered for ourselves. One thing I hope is discovered by others in reading this book (and others) is comics’ ability to attain the level of ‘high’ art without the need of cinema. Matthew Laiosa

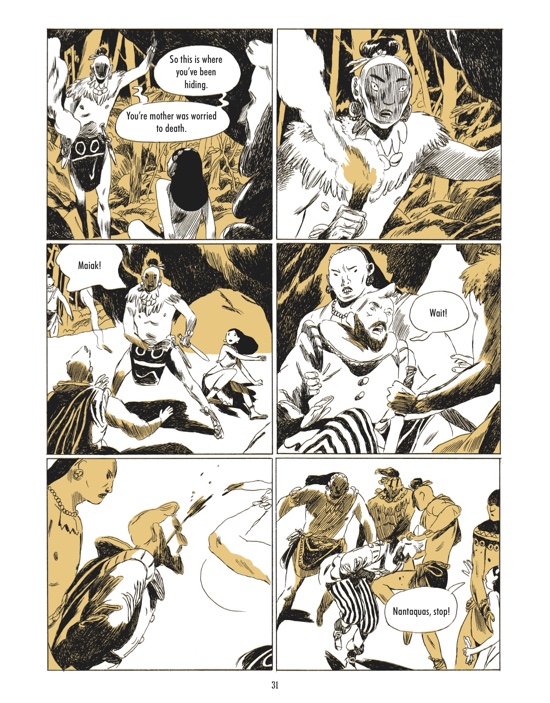

Loïc Locatelli-Kournwsky – Pocahontas: Princess of the New World

(Pegasus Books)

What makes writers want to tell Pocahontas’ story again and again? Was it her ability to defy what was expected of her? Was it her desire to coexist with others unlike her through understanding and non-violence? Was it her tragedy? Whatever the reason, Pocahontas has proved in every version of her story that she was one of the most modern women in what was America’s earliest history.

Unlike Disney’s focus on the more romantic and mythic elements of Pocahontas’ relationship with Captain John Smith, this version of the story depicts a young woman not acting out of love, but instead preventing an execution that she believes to be morally wrong. Her curiosity brings her closer to the English settlers, and her ethical beliefs once again lead her to warn the foreigners of an attack which eventually results in her exile from the Powhatan people. The book is cleverly divided into three parts, each titled after one of Pocahontas’ names reflecting a different stage of her life. Her life as a child is represented through her birth name, Matoaka, and it isn’t until she saves John Smith that she is renamed Pocahontas, which when translated means, ‘shameless whore.’ In the final chapter, Pocahontas converts to Christianity and adopts the name Rebecca, which erases the stigma of her given name, but also further divides her from the culture of her birth.

The art by Loïc Locatelli-Kournwsky balances simple and easy-to-read character designs with detailed environments and costumes. The black and white line art is augmented by vibrant yellow backgrounds helping to focus our attention on the most important elements of every panel. The most striking visual moment of the book is a dream sequence that heartbreakingly ties Pocahontas to our present. After spending some time touring England, Pocahontas wishes to return to her home in Virginia. On her journey she glimpses a modern world of soaring towers and cheap Native American costumes in gaudy department store windows. The vision alludes to the ultimate tragedy of Pocahontas and the failure of the two cultures to coexist, which might answer my initial question. Perhaps writers continue to tell Pocahontas’ story so that we can attempt to live by her example, an example that might be centuries old, but in constant need of reminding. Matthew Laiosa

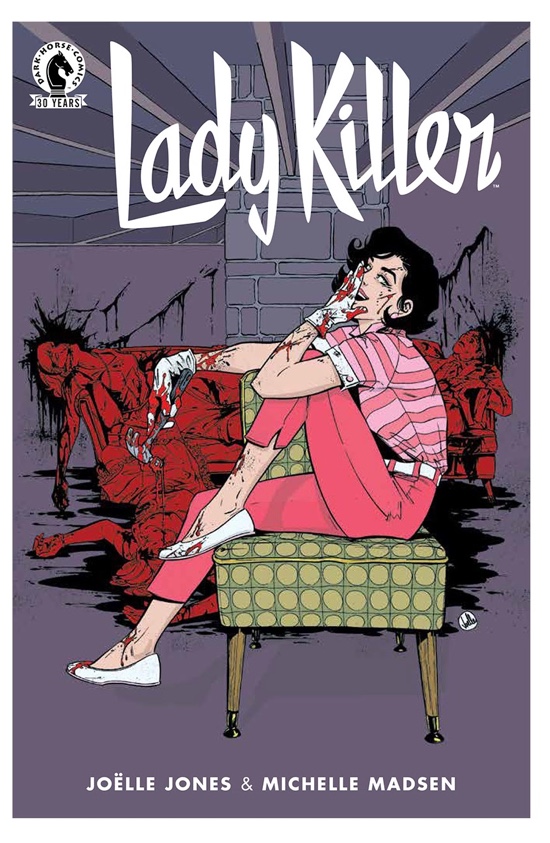

Joelle Jones – Ladykiller Vol. 2, Issue #1

(Dark Horse Comics)

How do you follow one of the best new series of 2015? By doing more of the same – but in the case of Ladykiller Volume 2, Issue #1, that’s a good thing.

Ladykiller Vol. 2, by writer and artist Joelle Jones, continues to follow the gory escapades of 1960s contract killer/suburban housewife Josie Schuller. Building on her struggle to balance murder and family life in the excellent Vol. 1, this first issue of a new story arc presents a new challenge for Josie as she goes into business for herself. With Issue #2 just out, now’s a great time to catch yourself up.

The issue opens with that mainstay of then-trendy suburban housewives’ social circles, the Tupperware party. Visually, it’s an excuse to showcase retro décor and stylish vintage dresses. For Josie, it’s an easy way to gain access to the people she’s been hired to kill. It also leads into one of the best bits of the issue: a delightfully sardonic sequence that juxtaposes peppy let’s-go-ladies! language with images of Josie hacking up a bloody corpse for disposal. “If you want to build a business of your own…you have to use a little imagination…and a lot of elbow grease,” her interior monologue advises while she brandishes a hacksaw above a dead woman’s arm.

Colorist Michelle Madsen’s lurid tones, which go past the conventional vivid palette of the 60s into the unsettling (but never losing sight of the comic’s violent aesthetic), provide a fitting backdrop for Ladykiller‘s head trauma close-ups and copious blood sprays. The blood is almost always black rather than red, which eases the revulsion factor and also hearkens back to monochrome horror movies of the period. It suggests that what we’re dealing with is just some fun female-driven ultraviolence created for thrills rather than grit.

However, Ladykiller is more than it pretends to be. Popular manifestations of the vintage revival tend to ignore the oppression and suffering of anyone who wasn’t a white man during the actual time period. Even Mad Men, which critiques Don Draper’s sexism and general mindset, simultaneously invites you to gush over sharp tailoring and sympathise with his wealthy, misogynist ennui. Ladykiller‘s violence undermines that facade, reminding us that the past is never as genteel as we want it to be – especially for women – and entertaining the hell out of us in the process. Kelly Kanayama