One of the last times I saw Daniel Kitson live, he had a bit about ‘If I watch a film at night instead of just some telly, I feel like I’ve really accomplished something.’ And so it was that late one night about a month ago, I had a couple of hours to spare and I saw that The Rabbi’s Cat was on Netflix. Despite following Joann Sfar on Instagram, I had yet to read any of his comics. The film – intriguing, poetic, and amusing, about a talking cat and his Rabbi owner in 1920’s Algeria setting off to find a mythical hidden city in the desert – convinced me I needed to rectify this. And as coincidences always seem to be hanging in the air, when I Google’d it, I found Sfar had a new comic due out soon (see below). Sfar also wrote and directed the Serge Gainsbourg biopic from 2010, a film I highly enjoyed. I’ll have to find some time to watch it again one night, feel really accomplished. We’ve got a lot of reviews to pack in this month, so let’s get to it, shall we? Oh, and check out Daniel Kitson’s work if you get the chance. One of the funniest men on the planet.

Frederik Peeters – Aama: 3. The Desert Of Mirrors

(pub. SelfMadeHero)

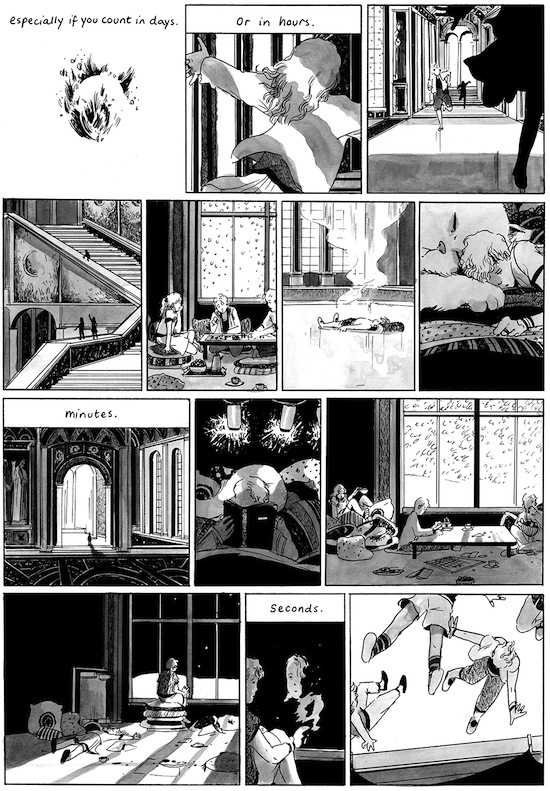

Aama continues to be one of The Best series out there. This third, and penultimate, book finds the reconnaissance mission deep inside the biological experiment they’ve come to the planet Ona(ji) to investigate. The world has already gone haywire but soon the pace is too much for even consciousness to keep up with and they’re gazing, for as long as they can hold the stare (in some cases not long at all) deep into the heart of complex technological and political problems, paranoia at their own personal involvements soon setting in. The very environment is morphing too rapidly for the characters to comprehend. Crazy shit like the ground they’re walking over suddenly transforming into a lake –or is it a creature? or some fabric of form that is a combination of the two… – only to rise and knock them airbourne to some other treacherous terrain or hypersonic armoured insectoids and other strange beings benevolent and malign materialising all over the place, before such places radically reimagine themselves into something else. Intertwined with deep realizations of their psyches, the journey is full of surprises as they continue to the heart of the experiment. Peeters’ art is seductive and exciting as ever, vibrantly coloured with a wonderful use of flow between different colour centres. Fans of Peeters’ work will note some self-referential panels – one showing blue pills (the title of his debut graphic novel from 2001), and a giant creature that looks a lot like one of the main characters from Koma makes an appearance. Highly recommended. – Aug Stone

Tillie Walden – The End Of Summer

(pub. Avery Hill)

An impressive debut from 19 year-old Vermontonian Tillie Walden. A beautiful looking book echoed in its lyrical, if not always understandable, plot. A large family with their servants, all tiny people, and a cat named Nemo who is four times their size are living in a massive, elegant home that they have sealed off for the winter. The season will last three years. Young Lars knows he’s going to die soon but is determined to spend his days with his twin sister Maja. He’s in love with her but there’s a darkness within Maja, hinted at but never fully revealed. When she secretly cuts her hair, it is a catastrophe that sends the whole household into upheaval. There is an etherealness to these characters that is well -grounded in the detailed grandeur of their surroundings. Particularly striking is the poetry of the final pages. – Aug Stone

Joann Sfar – Pascin

(pub. Uncivilized Books)

After a cursory flip through these pages, one would expect Sfar’s biography of Jewish modernist painter Julius Mortdecai Pincas to be positively pornographic. Panel after panel of general nakedness often, but far from always, leading to varied sexual acts. But this is misleading, and the book engages the reader without any recourse to baser appetites. This is a rather excellent account of the artist’s life, serving also as a discourse on the nature of our creative urges. Pascin’s life is an interesting one, shown here full of lovers, drinks and parties, friendships with artists and gangsters, at all times drawing, always drawing. The only childhood memories on show are when he’d sneak out, aged seven or eight, to go to brothels. A clue perhaps – as his mother is never seen, only a domineering father – to how drawing became even more intimate for him than sex. Religion – not taken very seriously but still taken – is discussed as is the nature of art. Pascin’s friend Antanas recounts how Kokoschka ‘claims – like Kafka, for literature – that reality is elusive…you have to walk all the way around it to get the full picture.’ And this is true of how Sfar present the book. There are entire episodes in which Pascin is not seen at all, instead we’re given glimpses into the lives of his models and friends. Which serve well to round out the image of the painter’s life. An enjoyable, thought-provoking read. And Sfar’s dreamy and expressive sketches are often lovely to behold. – Aug Stone

James Robinson (writer) and Greg Hinkle (artist) – Airboy #1

(pub. Image Comics)

As far as comics go, taking a much loved, if out of service, ‘Golden Age’ character and re-imagining them for a modern audience is fairly standard practise. Indeed, writer James Robinson’s lengthy, and successful, career has been defined by his re-invigoration of past-heroes such as Starman. Whether that’s how Robinson wishes to be remembered is of course a different matter altogether and just one of the many threads that gets tugged at in issue 1 of Airboy, not as may be expected a re-boot of the titular 1940s Nazi thumping hero but, until the final page at least, an unblinking look at the process and people involved in bringing these characters to the page.

Comics have an equally long tradition of meta-fictional tales but few writers have painted themselves in such an unforgiving light, this is more Superham on Rye than Grant Morrison featuring himself as a multiversal magician. In his self-examination, Robinson pulls few punches, the ‘James Robinson’ of Airboy is a morally and creatively bankrupt self-involved narcissist, a writer who has been phoning it in for some time now at DC with ever diminishing returns and knows it. In his own words, ‘they barely read my books as it is unless I’m killing Batman or some shit’. Offered the chance to re-launch the public domain Airboy for Image Comics, Robinson is swayed purely by the money on offer but with no story forthcoming he brings in artist Greg Hinkle to help develop it. In search of inspiration the pair set off on a Rabelaisian adventure that is both wonderfully exaggerated and yet all too familiar to anyone who has unexpectedly found themselves on a serious bender.

How much of this, both characterisation and plot, is true is up to the reader to decide but in contrast to the Robinson character’s opinion of his DC work, this is some of the best writing James Robinson has produced for years. Likewise industry newcomer Greg Hinkle brings this picaresque tale to life, treading the fine line between grotesque realism and comic exaggeration, none more so than when illustrating his avatar’s penis, an appendage deserving of a credit all of its own. With the final reveal the comic shifts tone from the cold brutality of realty into something more fantastical but even if subsequent issues tend more towards traditional comic hi-jinx Robinson and Hinkle have delivered one of the best debuts of 2015. – John Power

Various – Drawn & Quarterly 25

Let’s be clear about this: Drawn & Quarterly 25 is an essential purchase, with more than 750 pages featuring exclusive work by some of the finest artists working today. Be warned, though – it may prove considerably more expensive than the cover price suggests; if you don’t have a lot of D&Q comics this could be a gateway drug to the back catalogue.

As physical artefacts go, this is a particularly splendid book: hardback, with a great Tom Gauld cover, printed on lavish paper stock, and with a ribbon bookmark in the shade of orange used for text throughout. Such attention to detail functions as a reminder of the seriousness with which D&Q takes its work, as well as showing just how many of the greats it has published.

Inside there is a mixture of comics, essays, interviews, photos, correspondence and more. There are new pieces written specifically for this volume, excerpts from forthcoming works, rare strips from the past, and other unreleased material. The first 50 pages or so provide a history of D&Q, whetting the appetite for the comic strips that follow. Featuring work by Chester Brown, Joe Matt, Seth, Kate Beaton, Chris Ware, Adrian Tomine, Jillian Tamaki, Art Spiegelman, Rutu Modan, Gabrielle Bell, Joe Sacco, Daniel Clowes, Yoshihiro Tatsumi, Kevin Huizenga, Anders Nilsen, Guy Delisle, Julie Doucet, Peter Bagge, Gilbert Hernandez, Lynda Barry and many, many more, it’s hard to imagine any fan of indie comics not wanting to read this.

It’s also brilliantly sequenced, with essays and features building anticipation for many of the artists who appear on later pages. Some are represented solely by their work but others feature in photos, essays, and recollections. This context undoubtedly helps deepen the appreciation of their creations.

Some of the particular highlights: the first new work by Joe Matt for ten years, 14 pages that are as laugh out loud funny as his work always is (tempered somewhat by the realisation that if these pages are his total output since 2006, it may be a while before the book about his life in LA is released). Twenty pages of Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s A Drifting Life Part Two, the forthcoming continuation of his autobiography. Lynda Barry’s Sneaking Out, originally published in RAW. Several photos that show that Seth’s hat does, in fact, come off from time to time. Chester Brown’s The Hymn of the Pearl, originally produced for a (presumably far from festive) Christmas card. James Sturm’s sequence of strips. Adrian Tomine’s Optic Nerve. Anders Nilsen’s Me and the Universe. Kevin Huizenga’s My Career in Comics. Guy Delisle’s Just for Me. Tom Gauld’s cover and story. This list could go on and on.

Peter Bagge’s The Death of the Age of Stuff charts the dwindling financial opportunities open to cartoonists of his generation. Starting with the admission that he’s given up on physical media and local retailers, now consuming digital goods and shopping online, it moves to the discovery of his own work on filesharing sites then his attempts to earn a living through appearances at local comicons and the sale of original pages (at dwindling prices, natch). The whole anthology makes it pretty clear than publishing comics like these is no path to riches for anyone concerned. However, this beautiful volume, a defiant throwback to the age of stuff, deserves to sell very well, and is a reminder that physical media still has its place when both the form and the content is this good. Buy without hesitation. – Pete Redrup

Noah Van Sciver – Saint Cole

(pub. Fantagraphics)

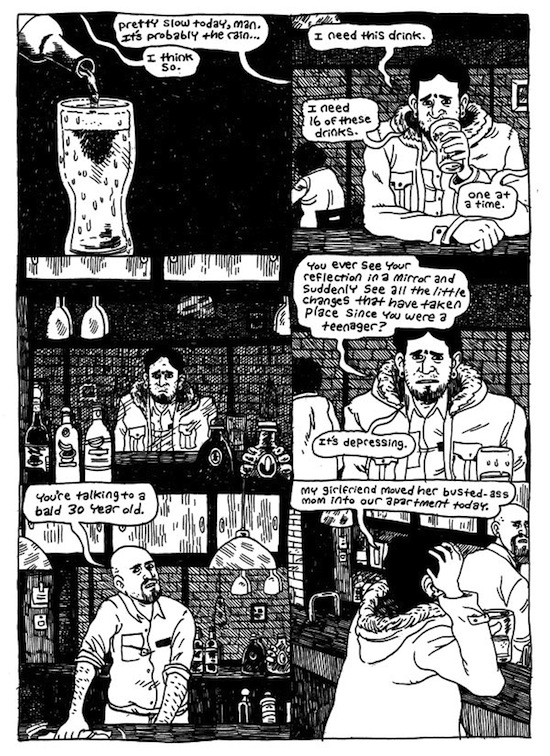

Before we’ve even reached the title page of Noah Van Sciver’s Saint Cole, we’re hit with ‘How did I let things get so out of hand? Within days I have destroyed everything’. No hyperbole here – this novel charts four days in the life of Joe, in which he manages a magnificently thorough spiral of self-destruction. It’s a quick read, likely to be consumed in a single sitting.

Joe is 28, and finds his life is on a trajectory some way distant from his ideal. He’s the father of an unplanned child, in a relationship that would most likely have ended if it weren’t for the kid, and the sole breadwinner in his family. Hard enough, but worse when that job is a waiter in a pizza restaurant, and he finds out his girlfriend’s mother is now living with them. She’s a liability with a range of substance abuse problems, and Joe himself isn’t exactly without issue in that department.

Some telltale signs you might be an alcoholic: drinking before work, repeatedly throwing up during work, stealing alcohol from work, spending so much on booze you can’t pay the rent, drinking (and vomiting) in the shower. Joe has them all, and he’s not happy about who he has become. ‘You ever see your reflection in a mirror and suddenly see all the little changes that have taken place since you were a teenager? It’s depressing’. His colleagues see it, but mostly turn a blind eye until his drunkenness leads to inappropriate behaviour at work.

Meanwhile, when his girlfriend Angela goes on a trip, Joe doesn’t cope well with the pharmacological temptations presented by having her mother as a houseguest. To reveal more would be to spoil the story, but suffice to say he lacks self-control.

The simple black and white panels tell the story in a direct, naturalistic way that doesn’t get in the way of the narrative but also repays a re-read, revealing plenty of subtle detail. The page borders and backgrounds alter as Joe loses control, creeping inside the panels as he sinks further into chaos. On one hand it’s hard to feel too much sympathy for Joe as the agent of his downfall, but at the same time a story of someone working too hard in a job, not quite scraping by, and not coping is very believable. Van Sciver has produced an accomplished work here, and he’s clearly a promising talent. – Pete Redrup

Seth – Palookaville 22

(pub. Drawn & Quarterly)

The latest issue of Seth’s Palookaville is, as anyone familiar with his work might expect, a thing of considerable beauty. This time it’s cloth-bound and wrapped in a striking green foil dust jacket. After 19 sporadically-released single issues, the Canadian cartoonist made the move in 2010 to approximately biennial hardcovers with a broader range of content. Here he continues the long-running Clyde Fans, the autobiographical Nothing Lasts, and also features a selection of photographs of his wife’s barbershop and related promotional materials designed by Seth, plus a fold-out strip about a barber.

Suffused with nostalgia and bitter melancholy, the elegant four colour panels showcase Seth’s distinctive visual style. Clyde Fans continues the story of the Matchcard brothers, owners of the titular fan company, set in his fictional town of Dominion. The ongoing saga first appeared in Palookaville 10 in 1998, and charts the demise of the family business through changing times (principally, the rise of air conditioning as a replacement for fans), whilst focusing on the ill-matched brothers’ relationship. This time Abe and Simon bicker and reminisce, particularly about their father’s unexpected departure, then Abe reflects on his personal and professional failures, his scorn directed inwards rather than at his sibling for the first time.

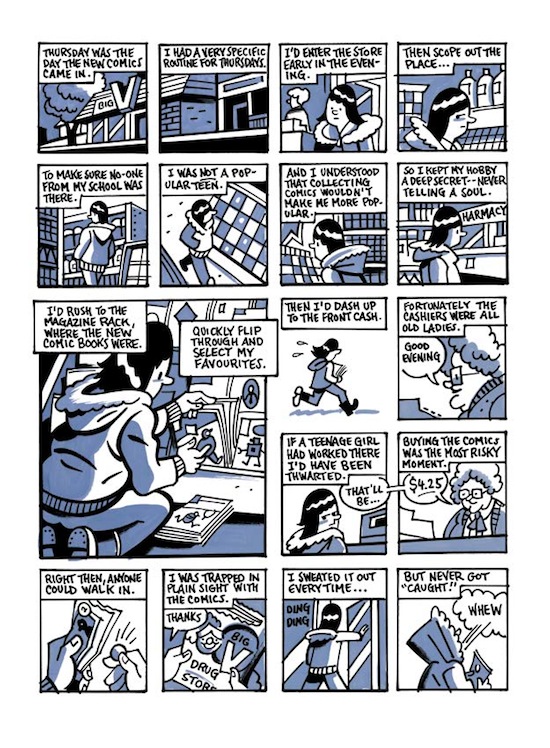

Both stories are linked by a concern for memory and the loss of the past, although not necessarily a desire for it to return. In Nothing Lasts, there’s often no obvious connection between the images and the words – it’s like we’re walking round his old neighbourhood with him, while he reflects on his childhood, revealing and concealing in equal measure. This languid pacing is a common element in Seth’s work. We learn about his parents – very close to his mother, more distant from his father. The paternal relationship was clearly complicated, and there’s probably some echo of this in Clyde Fans. He also writes about how he became interested in reading then producing comics, describing his furtive teenage habits of buying them in a local shop, desperately hoping to avoid being seen by classmates, noting that this attitude was more appropriate for pornography. It’s hard not to draw parallels between the panels in his friend Chester Brown’s The Playboy in which he describes stealthily shopping for that magazine in his own teenage years.

This is another great entry in the Palookaville series. It’s not an ideal starting point for neophytes, consisting as it does of ongoing works continued but not concluded. However, any regular readers will want to pick this one up. – Pete Redrup

Chuck Palahniuk (writer) and Cameron Stewart (artist) – Fight Club 2 #1

(pub. Dark Horse)

Taking one of the most successful cult franchises of recent memory and dragging its sequel into the pages of a comic book is a curious move on the part of Fight Club author Chuck Palahniuk, but a successful one as far as this first episode demonstrates. It shows us the narrator of the original story (he uses the name Sebastian, possibly just a fiction) ten years on from the events of the original, now married to Marla and with a young son. Deadened by his use of medication and stuck in wearing routine, he describes himself as ‘happy’ – even as Marla is wearied and borderline disgusted by his ageing softness. Yet wherever he goes, men with faces like bloody, tenderised hamburger bow respectfully and address him as ‘sir’. The return of Tyler Durden is imminent. Alongside Cameron Stewart’s naturalistic but noirish art, what pleases most is that Palahniuk seems to get the mechanics of comic book scripting, pacing the story well and ending on a heart-flipping cliffhanger. – David Pollock

John Smith, Colin MacNeil, Sean Phillips and more – Devlin Waugh: Red Tide

(pub. Rebellion)

Of the many writers who graduated from cult British sci-fi comic 2000AD to American stardom throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s (Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Mark Millar, Peter Milligan, and so on), John Smith was a real talent who slipped by largely unnoticed. Continuing his association with the title ever since, he’s been involved in a number of series, although few have been as memorable as the gay vampire and assassin for the Vatican, Devlin Waugh, whose second book of adventures are collected here. Created by Smith and artist Sean Phillips for the spin-off Judge Dredd Megazine, Waugh’s adventures are as over-the-top and sexually-charged as ‘90s comics ever were, although Smith remains respectful of the character’s sexuality (a first for 2000AD, at least overtly) by concentrating on the action and the bloodletting as Waugh encounters aquatic vampires, is held captive and forced to ‘bite fight’ – pit fight using just his teeth – and infected with ‘psycho-venereal disease’ by telepathic ovulations laid in his brain by a dying monster. Main series artist Colin MacNeil’s work is dark and atmospheric but a vivid pleasure to follow, while Smith’s writing is a feast of oddball sci-fi invention and sharp-witted pulp action. – David Pollock

Andrew MacLean – ApocalyptiGirl: An Aria For The End Times

(pub. Dark Horse)

Andrew MacLean is something of a revelation in the indie-comics world. His ‘Head Lopper’comic was a much needed tongue-in-cheek take on the post-Game of Thrones seriousness of monsters, swords and sorcery. ApocalyptiGirl is his first graphic novel, and it’s a short, sharp but tender spin on humanity, religion and the environment. Aria, our protagonist, is the only non-gang member human left on a post-apocalyptic Earth-like planet. The planet itself is recovering – Mother Nature’s amazing powers of healing are re-taking the cities, swamping them with bountiful fruits and lush green grasslands. Two factions are at war over this landscape – the Grey Beards and the Blue Stripes. Their war is based on differing views with regards to a great, but hidden, source of power. Aria has a mission, to find this lost power source, that may not be a God at all, but something technological that has become hidden in the bowls of the planet. It emits a signal, which Aria can track, and it’s always tantalisingly close, but almost impossible to pinpoint. Her only friend in this task is her cat, Jelly Bean. Whilst this may sound like a rather routine sci-fi comic, there’s twists aplenty, and MacLean’s lean, mean story-telling coupled with his angular and sparse artwork makes it read like a sharp thriller where the action throws itself at you from impossible angles. It has a breathtaking pace, yet the ending is surprisingly charming and, perhaps, overly romantic. The novel can easily be read in one sitting, which just ensures you start again – spotting different nuances in each panel and recognising little winks and nods to past sci-fi classics. MacLean has certainly shown himself to be a one of a kind, and his heady mix of East and West cultures and styles meld together in a refreshingly unique manner. He’s becoming an essential name to follow. – Rich Hughes