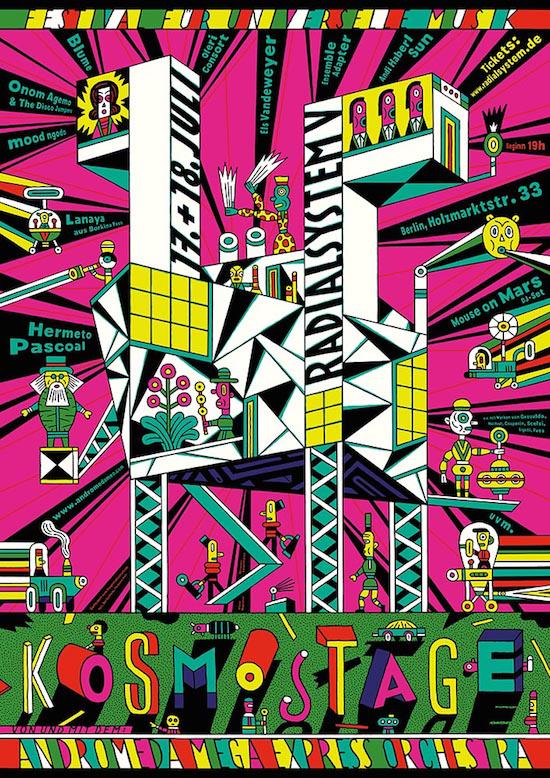

Organised by Berlin’s Andromeda Mega Express Orchestra, the second Kosmostage festival brings together music from Burkina-Faso, Mali and Brazil, free and groove-based improvisation, modern composition, medieval choral music, a smattering of noise and classic Berlin electronica. A cynical voice in the back of my head had caviled that such a gathering might be somewhat worthy or contrived in practice. My inner grouch can go and boil his head, for Kosmostage proves to be a winningly fluid and natural affair. Eclecticism can sometimes be a by-word for context-free programming, but Kosmostage is smartly curated to create an unforced sense of dialogue.

The festival is something of a family affair, with members of the Orchestra presenting their own projects and collaborating with guests on both nights. Saxophonist Johannes Schleiermacher, who turns out to be a festival star, opens the first night with his group Onom Agemo & The Disco Jumpers. Not unlike London’s Heliocentrics, this quintet offer a spacey take on vintage Afro-funk, making it their own through spacey effects and free-improv moves. Jörg Hopfapfel’s Farfisa and synth come drenched in cosmic echoes, while Schleiermacher and drummer Bernd Oezsevim push against the rolling grooves with controlled bursts of free blowing and Han Bennink-style frame-rattling.

The Onom rhythm section ease the transition to Lanaya’s first set of the weekend, holding down a rolling groove while the Burkinabé and Malian musicians gradually take over. The Berlin-based group offers a singular fusion of Burkinabe and West African traditions, with Djelifily Sako’s kora rippling over trance rhythms on djembe, doundoun and calabash. Madou Zon’s balafon playing is particularly impressive, a virtuosic display that proudly stands alongside Els Vandeweyer’s innovative playing of its modern descendent, the vibraphone. Briefly joining Lanaya before her own solo set, Vandeweyer takes a respectful background role, adding accents and shimmering chords to the polyrhythmic improvisations.

Vandewyer is among a crop of young players – shout out to Peter Brötzmann collaborator Jason Adasiewicz and Derby’s own Corey Mwamba – to reinvent the vibraphone as a free-improvisation instrument, using a range of extended techniques and objects to disrupt its dreamy sound. There are shades of John Cage’s prepared piano in the way she jams scrunched up drink cans between the keys and drapes chains across the surface of her instrument. The effect is to dampen the notes, adding a rattling metallic edge to its resonant notes. Using soft mallets she conjures billowing clouds of tone; harder mallets bring out the instrument’s woody, percussive side, taking it closer to Zon’s balafon. Later in the evening, Vandeweyer is joined by Schleiermacher for a duo improvisation. This is a strong pairing, with both players exploring the connection between body sounds and the materiality of their instruments. Vandeweyer’s shimmering tones and mechanical abstractions open up plenty of space for Schleiermacher to work through a range of puckering sounds and spit valve gurgles, smeared tones and lusty multiphonic smooches. Their deep listening and sensitive interplay is a delight; it would be great to hear more from this pair.

Their duet comes as part of a mid-evening programme of short sets, which take place on portable stages arranged around the room, allowing for a near-continuous flow of music. Keyboardist Jai Lin moves from the exquisite 18th century courtly music of Francois Couperin to the modernist harpsichord of Ligeti’s ‘Passacaglia Ungherese’. Such intricately structured music makes for an interesting contrast with the more abstract, albeit no less rigorous, approach of Vandeweyer and Schleiermacher. Berlin contemporary music group Ensemble Adapter then perform David Brynjar Franzson’s 2009 composition ‘The Principles Of Order’, a tightly controlled work for xylophone, harp and bass clarinet. With its painstakingly plotted scrapes, drones and twangs the piece connects to both the classical and free improv traditions. In a triumph of lateral thinking, an ecstatic drum improvisation from Lanaya sets up Adapter’s realization of Simon Løffler’s noise piece ‘b’.

Underground music’s infiltration of the classical concert hall is producing some intriguing hybrids and ‘b’ is a witty and exciting play on the conventions of both worlds. Reading from sheet music, the players revel in deliberate gestures, manipulating the feedback from a no-input mixer with pedals, contact mics and movement. Rather than build a flaming wall of noise, Adapter assemble disjointed bursts of fuzzy static and arcs of dirty white light into ragged cyborg music, as if Einsturzende Neubauten had kidnapped Kraftwerk’s robots and flooded their circuits with corrupted battery acid.

Saturday kicks off with the post-modern jazz of BLUME and AMEO drummer Andi Haberl’s project Sun. BLUME deftly combine ECM jazz and Latin-tinged horn melodies with a rhythmic sensibility steeped in electronica and post-rock. Yet just when you think it’s saxophonist Wanja Slavin and AEMO trumpeter Magnus Schriefl who are the traditionalists, they wrongfoot you by processing their horns through a patch which smooths off the attack to create an oddly glassy tone. Led by AEMO drummer Peter Gall, Sun are reminiscent of post-jazz outfits like Polar Bear, with a touch of Tortoise and In Rainbows era Radiohead to the spidery guitars and twinkling glockenspiel. The finely drawn themes and tightly-wound grooves eventually unravel with Haberl’s expressive free drumming, the release proving hugely satisfying.

The mid-evening programme begins with Giacinto Scelsi’s 1968 piece ‘Okanagon’, where bowed bass drones are lain against the sheet metal harmonics of a concert harp played with a metal file. As the piece progresses, percussionist Maria Schneider’s plangent gong looms over the sound of Anna Viechtl and Oliver Potratz’s tapping on the bodies of their instruments. We then alternate between Oferi Consort playing choral music from the 13th to 16th century and Lanaya playing different kinds of traditionan Burkinabé and Malian music, featuring some beautiful singing from Mama Sanou and some rousing djembe workouts. The juxtaposition works well, putting African and European traditions on an equal footing.

Unfortunately a loo-break means I can’t get back in for Kosmostage-Festival-Ensemble’s take on the Prelude from Charles Ive’s ‘Universe Symphony’. I presume the piece was to be a vehicle for the festival’s guiding notion of universal music, with the players drawn from different acts. From the courtyard outside I can hear an almighty clatter of drums at one point, but I can’t help but wish I’d been inside.

And so to the headliner on both nights, Brazilian jazz maverick Hermeto Pascoal. Beloved in his home country and in Europe, Pascoal is probably best known in the US and UK for his contributions to Miles Davis’s ridiculously awesome 1971 album Live Evil. Miles said that Pascoal was ‘the most impressive musician in the world’ and at 79, the Brazilian’s dexterity on keyboards, accordion, melodica and various home-made instruments is a wonder to behold. While his soprano saxophone is left untouched, he does perform off-beat solos on a battered metal teapot with a trumpet mouthpiece in its spout, and a traditional Brazilian cow horn. There’s even a bit of Robert Wyatt-style hand trumpet, his hands making melancholy wah-wah effects as he sings.

These sets are a celebration of Pascoal’s music, but his role is as a featured guest than leader. This is AMEO leader Daniel Glatzel’s baby, with the ensemble playing his arrangements of Pascoal’s music. The other guests are Fabio Pascoal on percussion and the remarkable Aline Morena, who arguably steals the show with her wildly intricate vocal parts. Pascoal’s music has that uncanny quality of sounding quite accessible and ‘light’ while simultaneously being really fucking weird. It’s not just in the man’s eccentric instrumentation, but his melodies and arrangements, which are breezy and playful, while also being fiendishly complex, like baroque fugues refracted through jazz and Brazilian folk. Morena sings these parts in perfect unison with the orchestra, making octave leaps and multi-syllabic phrases sound delightfully musical, when they could so easily be a ghastly display of empty virtuosity. Her two solo features are a blast: a brilliantly skewed Mozart aria, complete with vertiginous soprano runs, and an ensemble pieced around her percussive dancing and singing.

Glatzel’s arrangements are superb, bringing out Pascoal’s connection to the European classical tradition, without compromising the Latin rhythms or post-bossa harmonic language. The jazz elements come through strongly, whether in the bop trumpet solos of Magnus Schriefl and Richard Koch, or the freer blowing of Schleiermacher and Glatzel himself, all bubbling cauldrons and fire engine sirens. There’s so much going on, it’s hard to fit it all in to a coherent review. Some impressions: Isabelle Klemt’s jagged cello syncopations weaving in and out of the swinging violin parts. Woodblocks and tambourines dancing over dreamy vibraphones. Fabio Pascoal letting off samba whistles and duck calls, before playing a solo on squeaky toy pigs. The whole orchestra downing instruments to pick up bottles of water and become one giant glass harmonica.

AMEO’s sets run to almost three hours on both nights, with a large chunk of the final third being given over to a rambling ‘audience with Pascoal’ section that is mediated through a translator. ‘Sing free because we have to be crazier than the world,’ he compels us. ‘Don’t be a robot! Find that love within every human’. Pascoal performs a piano solo, duets with a flautist on his DX7 synth and finally picks up his accordion to lead the orchestra through a glorious rendition of ‘Garrote’. These are long sets, but even in the frustrating moments where Pascoal goes off on a philosophical tangent, it’s a pleasure to be in his company. Immense credit is due to Gatzel and AMEO for realising Pascoal’s music so vividly.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/18463-festival-report-kosmostage-review” data-width="550">