I read Jon Leon’s latest pamphlet Mono-Haha late last year while flying to London Stansted from George Best Airport Belfast, having been charged £184 by easyJet for having the initial ‘S’ printed on my boarding pass where my first name should have been. I finished it well inside the 50-minute flight-time. ‘Art is redemptive’, Leon writes, surprising himself at one point in the ‘five panoramic art reviews from 2012’ that make up the publication: really a set of anaesthetised prose poems within which Leon’s distinctively vacated persona pinballs between bookstores, gallery shows, clubs and movies, over a slow burning New York summer: “I walked by Comme des Garcons. I went to D’Amelio. I saw some collages by Deborah Ligorio. They were nice.”

I can’t even remember how I heard about Jon Leon, but I have been talking about his work to anyone who’ll listen for a few years now. The author of a series of crisply titled and impossible to acquire limited-run chapbooks (Hit Wave, Kasmir, White Girls, The Hot Tub…), for a poet he seems a strangely unaffiliated, even isolated figure, orbiting the worlds of fashion and art with a sort of listless fervour. His writing attracts me partly as it sits among an intrigue of kindred influences, most notably I think the Baudelaire of Paris Spleen. “Poetry my sinister double traitor”, writes Leon in ‘Die With These Bitches’, distorting and echoing back Baudelaire’s ‘Hypocrite lecteur, – mon semblable, – mon frère!’ from a hundred and fifty years in the future. Poetry for Leon seems to enable the projection of a dark twin; his persona, established over ‘retrospective’ collections like Malady Of The Century (2012) is dissolute, voyeuristic, glazed, and endlessly quotable: “I smoke crack because I’m Satan”; “You know you’ve finally made it when you’re just dating models only”; “My dick is the monarchy”; “because there is nothing cuntface”, to name a few within a ten-page spread of Mankind (also 2012). Guiding you through the infernal nightscapes of 21st century Los Angeles, Miami and New York, his voice is convincingly in and of that world, ‘out there’ like a malevolent doppelganger, partaking of forbidden draughts, ‘smelling the drugs’, and implicating you in its excesses. The agency his poetry advocates reminds me of Baudelaire’s elaborate nastiness in ‘The Bad Glazier’, or even of Virgil encouraging Dante to contribute to the torments of those in Hell rather than alleviate them.

We should hang most people

I believe I’m terrifying

I know that they are

They are just like forgotten except they aren’t even existing

They are the world’s specie

Like a kind of gold coin

The way I like to store up gold coins to pelt

Pelt whores dagger and menace

(‘Die With These Bitches’)

It might be more tempting than usual to wonder to what extent the poetry corresponds to life, but it’s pretty much impossible to measure any gap between intent and effect here; Leon has maintained an unlikely level of obscurity, when most writers are engaged in direct forms of self-exposure. Rumoured to be living in several different cities, approached cautiously even by his devotees, there is something precarious about his public identity, a deliberate reluctance to intrude on the work with an authorial perspective. I’ve heard about his repeated ‘retirements’ from poetry (every book is both comeback and last book), and seen at least two self-run blogs disappear overnight, which would seem to evidence a two-mindedness about the effects of a conventional online presence: “I feel it is distracting to the work, and that this is a time to focus on the books of the future”, he wrote to Ben Fama, declining to be interviewed in 2012.

This courting of the image seems to me reminiscent of Richard Prince, the American artist most in thrall to modern emptiness and its surfaces. In ‘Overdetermined’ (1983), apparently a veiled third-person account of his own personality, Prince writes:

“His image did have a tonality. Something that was common like a world

sign…and his fear about hating himself for any rupture in his look was what he

sweated the most. A tell-tale seam, a visibility.”

For Prince, the maintenance of an impervious artist-brand is encompassing, every appearance an opportunity for image reinforcement: “Partying was an essential ingredient, an accent.” If Leon is similarly concerned with preventing cracks from spreading in his pristine biographies, his studied remoteness may have something in common too with the New York poet of commerce and candour, Frederick Seidel (whose Nice Weather (2013) Leon picks up on p.13 of Mono-Haha).

Seidel has never given a public reading, and while his poems have a grander, older, more international flavour, pairing the names of German politicians with Italian film directors and Italian motorcycles, his flair is also for representing the unapologetic enjoyment of privilege: five or six telescopic podiums of privilege, in his case. The poem which still disturbs and delights me the most is probably ‘Pressed Duck’ (from Sunrise, 1979) – here, we become familiar with an intimate, highly affluent, elite social grouping, gathered for a dinner party: “green as grapes/ A cluster of February birthdays…elegant and guileless // Above our English clothes / And Cartier watches.” The poem ends:

Chauveron cut

The wine-red meat off the carcasses.

His duck press was the only one in New York.

He stirred brandy into the blood

While we watched. Elaine said, “Why do we need anybody else?

We’re the world.”

Seidel’s work routinely confounds any expectation that the poet be some sort of exemplar of moral standards and artistic responsibility, yet for him this poem seems particularly finely poised. The familiar justification for poetry which indulges or appears to endorse the display of less than noble sentiments – that an engagement with cruelty and excess, even one this fluent, implies a dimension of criticality – can’t really apply here. As Joyelle McSweeney writes of Leon, “I don’t feel critique in these poems.” Seidel refuses to turn the scene into a grotesquery of riches. There remains, though, something quietly terrible, vampiric, about the gathering: the guests are literally drinking blood, and some kind of knowledge of the suffering on which their wealth is predicated seems to reside in the image of the bleeding duck carcass. There is a strain of malice in the candle-flames and laughter, the sheer geniality of the occasion, where the insignias of timeless brands are picked out in the mood lighting, soft co-ordinates that generate its luxurious ambience. Yet the account never becomes crude or exaggerated, the cool ironizing that one might predict fails to coat and harden our perspective. The effect is exclusive and perfectly wounding: I’m puzzled by own pleasure.

It would be easy, I think, for a poem like this to invite condemnation from its reader, to ask you to side with it against its setting, rather than maintaining this delicate, dangerous balance – on one side approval, even envy, on the other, disgust, the comfort of derision. The poem doesn’t lapse into either attitude, but holds its formal pose: its suspension of judgement is a variety of good manners. Seidel’s own complicity and, more shockingly, his obvious affection is key to this – he might appear as a slightly hesitant, reserved figure, speaking less, noticing more, but he enjoys his company as much as he seems to enjoy gauging our reaction to them: he’s not going to condemn them for us. He wouldn’t presume.

Perhaps there is something untrustworthy about a poem that wants you on its team too badly, or that tries to reflect (what it imagines is) your own view back at you: it’s dislocating, like catching sight of yourself nodding in a mirror. Witold Gombrowicz puts it nicely in his Diary: “I agree…but at the same time, I am sceptical about my own affirmation.” I often feel like this when a poem tries to instruct too directly: the supposedly digestible nugget always sticks in the throat. Gombrowicz:

“The moral [is] not only the work of people with an especially subtle feeling of

profundity, but also, of people who perfect one another in that moral. Their

thought is only superficially individualistic. It is concerned with the individual, but it

is not the product of an individual.”

Sometimes when I’m reading Seidel I think something like – ‘Power is speaking…with its properly obscene dimension present’ (in Slavoj Zizek voice) – in that the way his poems accommodate power feels like the antithesis of the way politicians or corporations speak from power, especially when they’re attempting to apologise or sympathise or otherwise sound human. In an analogous way, when poetry moralises it stops being convincing, not only because it shows its agenda, but because it begins to speak in generalities, and this ends up generalising the reader as well: our response is anticipated, levelled. For the poem’s purposes every outcome becomes the same.

The results of Seidel’s poem, meanwhile, are unpredictable. Maybe I actually believe that ‘Pressed Duck’ is too troubling, too perversely ambivalent, to be co-opted as apologia for a ruling elite, for example, (“We’re the world” sounds too much like honesty<su[>1) or subsumed into a convenient liberal narrative. A poem with a paraphrasable ‘message’ can always be made use of, because it lacks a dimension that alters depending on its context and readership. Presently, this usage is most likely to be simply to prove the variety, diversity and freedom of the cultural landscape. Seidel seems to suggest that there are ways that writing or art can make itself detrimental, or at least useless, to that project – that it can somehow indicate the limits of the celebrated autonomy of art from within its conditions. Positioned on the threshold of a plausible transgression, the poem can’t be reliably read as being uncomplicatedly approving or uncomplicatedly critical of its theatre of lethal affluence and barbarous good taste, but resists either attempt equally. Perhaps it’s a sort of duty: to report back on the far reaches of the American dream.

Seidel’s own defence, in the few interviews he has granted, for sentiments such as the notorious, “A naked woman my age is just a total nightmare”, has always been the self-explanatory ‘I thought it was a good line’ – in a way an unimpeachable statement when you have as many good lines as Seidel (a favourite, from the late 1990s: “This century needs to end. / To modern art I say / It’s been real.”), and is yet another thing that makes him sound about twice as modern as most poets a quarter of his age. In a different interview he describes using a computer for the first time to compose a poem – his girlfriend was a PhD in electrical engineering at Columbia, so he was able to ‘receive clearance’ to visit the huge machine, a ‘Defense Department mainframe’, alone in its ventilated room, and saw that it was the future: “What hooked me was the way you could instantly change the shape of the stanza, the length of the line. It was the instantly part that got me.”

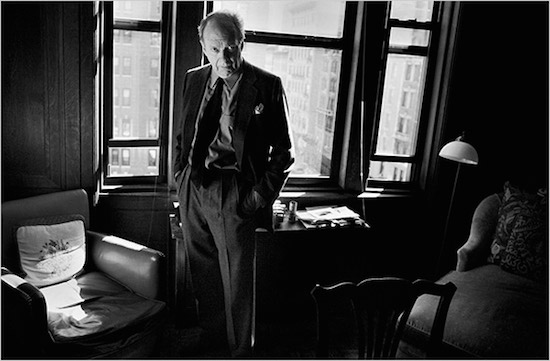

Michael Hofmann’s argument that any biographical reading is nullified by Seidel’s determination to offend, suggesting instead the idea of ‘the poet as the meat-slicing machine’, is readily supported by poems double-loaded with disclaimers, from the cod-Rimbaud of ‘I isn’t anything’, to the grisly ‘My face is falling off my face’, to the plain witty ‘My name is Fred Seidel, / And I paid for this ad.’ I find Hofmann’s assertion that ‘the lines [don’t] greatly matter’ to be obviously not true, though: while what’s foregrounded when we read Seidel, via his repetitiveness and heavy, almost mechanical rhymes, is, if you like, the blade setting that portions his material, there is still indisputably substance. The misogyny, as with Baudelaire, is total: it reads all the way through, like a seam of fat. Seidel’s other aggressive focus is American race relations, to which he returns continually, as if to a sore point, a cut, an unhealing. These subjects seem to me to be selected precisely because of their discomforting resonance with Seidel’s ‘insider’ status (the pool parties with former presidents, the recollections of ‘negro’ doormen, the private toasting of the war), and especially to the predictable liberal sensibilities of a poetry audience. The provocation can be disarming, thrilling in its directness, but it is at the same time undeniably wounding, frightening as perhaps only real wealth can be frightening. (It is us in the slicer, near the blade’s singing edge.) The last lines of Seidel’s 2006 book Ooga-booga are: ‘Open the mummy case of this text respectfully. / You find no one inside.’ Another dummy, another disclaimer, but it should be noted that this sarcophagus bears the image of a rich old white guy, and he’s not even dead. What I mean is that reading Seidel must involve the continual referral to the image of the poet, developed over several books and some judiciously-managed biographical material (those meetings with Pound at St Elizabeth’s, for instance, are significant) – and this is also why he is so easy to mis- and/or under-read. In a way the image on the book jacket – his rigid suit, his stern inquiring look, its privilege and prestige – is his foremost subject. Fantasies and confessions blur at his poetry’s point of origin, a site of admissions but also of inventions and provocations: “My big blue heartfelt eyes hid in a hood and white sheets / Completely ready to burn a cross and buy a gun” (‘Back Then’). As with Leon’s reticence, all we can infer from Seidel, perhaps, is his refusal to consider aesthetic concerns separately from moral ones. As usual, Sontag is best:

“Only when works of art are reduced to statements which propose a specific

content, and when morality is identified with a particular morality…only then can a

work of art be thought to undermine morality. Indeed, only then can the full

distinction between the aesthetic and the ethical be made.”

With most literary forms we are used to reading against appearances – hence the legal copy at the start of novels, vouching for our urge to locate the ‘truth’ in fiction, or conversely our reception of biography with its equivalent impulse to discover invention masquerading as fact (cf. James Frey). Seidel’s work exposes the artificiality of these distinctions. ‘Elegant and guileless’, either everything is valid, true, ‘confessional’, or nothing is, and it’s all assembled from parts somehow, sliced from public life – and yet we’re forced to countenance both possibilities, to hold them in mind at once. In short, I don’t want to be sure: all I can say is that I am seduced and I am repelled. Sontag again: “our response to art is “moral” insofar as it is, precisely, the enlivening of our sensibility and moral consciousness.”

I have made Seidel exemplary here, but a similar inclination, or better, reluctance, can be found in other poets – the belief that, as Gombrowicz has it, the author should ‘never speak to me directly.’ Michael Robbins

I have a quality that is like a libertine…

Which is that I have a great desire to enjoy my own disgust…

If I am a poet I am the worst kind of poet…

Someone once thought that a poem should be more than an elaborate “fuck

you,” but I did not think it.

(‘Prefaces’)

I don’t think I can think of another poet who resents poetry so much (this is not a case of ‘I, too, dislike it,’ which she makes look mild: “But, ‘I have nothing to say to Marianne Moore and she has nothing to say to me!’” as Minnis sasses in one poem), and it’s a natural paradox that many claim Minnis as their favourite poet. Poets hating on poetry has a grand tradition, and the emergence of a new style often seems motivated by contempt for another. Accompanying this frequently is a sort of glee, the impetuous joy of the young deposer. I read Minnis as the purveyor of an enhanced, mordant femininity, recording the simultaneous disintegration and amplification of glamour as it enters a disaster zone, “a shimmer like sequins flushing down the toilet”, through an unequalled abundance of decadent, obscene, renunciatory images: more killer lines per square-foot than Seidel even. Her subject is poetry, its awfulness, its pretensions, its ‘business’, and she arrives armed. These really are at random: “Often I find myself defending my own narcissism”; “When I write a poem it’s like looking through a knothole into a velvet fuckpad…” ; “If poetry is dead…then good.”

There is a mirror-diagonal to Jon Leon’s pale, predatory masculinity here, a speaker just as fixated on the dire predicament of the poet (both mention poetry continually, usually to blame it for something; ‘the insight which comes as a kiss / and follows as a curse’, as O’ Hara wrote). Minnis shifts between drunkenness, brilliance and abject despair, but underneath, the entire poetic enterprise is conceived as a ‘dark dark error’ – you feel she is ready to abandon it at any moment. Her protracted use of ellipses, her formal innovation, seems to follow from this. In the shorter poems they flash past on quick revolutions, as if her voice is trapped on a tightening spiral. She’s just warming up though, and stretches of speechless dots come to fill whole pages, a rising whirr as the speed of the machinery increases. The lines that slide out intermittently are marbled pink and grey: decay and luxury, layering like carpaccio.

Minnis has a poem in her first book Zirconia (2001) (there are three collections, each a little more fatigued, more urgent than the last) which reads like a fantastical account of how she came to be a poet: ‘The Torturers’ is a tragic, picaresque coming of age tale in six flattened blocks of prose, a thoroughly American story of abandonment and aimless wandering. Hated by her parents, the child narrator is left at a pawnshop, where her fascination with silvery, shiny, sharp objects begins: spurs, cutlery, then knives, which she ‘sells to delinquents.’ She becomes attached to a harmonica when a vagrant compares its sound to that of drawing a blade (“I played it until I hated it and that was music”), and it permits her a kind of itinerant existence; at night she covers it with her hands “so that none of the silver glinted.” Later she works in a bar cutting limes. Later still she walks the docks where shiny tuna give her “somber memories about my harmonica.” Throughout the poem, the I’s pattern of appearances mimics the tantalising, malevolent glinting of the objects it treasures, recurring like the edge of a blade, or an evil thread that sews the past together (a demonic sewing machine instead of a meat-slicer). Near the end of the poem, the narrator discovers ‘the torturer’s ballroom’, where she works as a ‘mirror washer’, until noticing she’s never seen a torturer there. She hides in one of the torturers’ ermine cloaks. When the torturer puts it on she wraps her arms around them: “And that is how I became head torturer.”

One of the few available biographical details about Minnis is that her father is a dentist, and the poem’s fascination with sharp instruments and the pain they cause is wryly connected, maybe… but really the poem offers a graph of mastery, a way out of solitude as something to be endured, finding at the poem’s close a terrible, lonely glory instead. The narrator practices with the tools of her unnamed trade, up until the moment she literally put on the role that makes use of them – applying her skills to her own story. In the telling, the stitching together of indignities and hardships, she becomes the torturer who oversees her past ordeals. Joyelle McSweeney has said of Minnis’s work that “‘I’ marks the site where agency, thought, organized, individual consciousness is not.” Here, the ‘I’ exists as the object of narrative forces, up to the moment of empowerment, discovery, consciousness. Is it poetry? It saves her, but she is trapped inside its ermine cloak.

As an ‘alternative biography’

“A friend of mine once told me that poems should last at least 100 years…But it

makes me fall into a stupor to think of what can last for 100 years. I don’t want that! I

want something that will last like 2 years.”

Among poets this is a truly shocking statement – almost blasphemy. The dream of future readers is what the unpopularity of poetry is wagered against. Long term survival is recognised as the true test, and like religious faith, where justice now is relinquished for justice in the next life, poets are happy to transfer their hopes and ambitions to imaginary future splendour, when all the appreciation owed them is suddenly and mysteriously paid in full. Of course there is an easy, pre-emptive power in this renunciation: declaring disinterest, quitting before you’re fired. But to reject the utopian promise of a poem, that it awaits understanding by some ideal subjectivity, for me also points to a radical premise beneath the apparent flippancy. To renounce the future means to prioritise the present. Silence in the future means speaking now. “People in the Future Need To Die,” as Dan Hoy, a collaborator of Leon’s, puts it in his video, The People (2011).

Minnis’s poetry is at least partly preoccupied with how poetry needs to address its own moment (“Poetry has to update or I will begin to rip my sleeves down”), how it can be renewed perhaps only at the expense of the artistic idealism which our culture approvingly murmurs about whenever it’s asked what poetry is ‘for’: draining it, drinking its blood, sacrificing it in order to make something new.

She accomplishes this for the most part by embracing ‘badness’. Her 2007 collection Bad Bad (as opposed to ‘good bad’?) has a kitsch candy-stripe cover, sarcastic blurbs (‘Decadent! Childish!’) and mock-gothic typefaces; 2009’s Poemland parodies publishing’s glum commerciality by making a motif of the book’s barcode. All of this works to clear the dust of poetic decorum from the work, uncovering its bleak circumstances. In a lo-tech art form, where the shunning of ‘progress’ is accepted, the crisis is – what if all that’s available in the way of authentic expression is to register one’s own dissatisfaction? ‘Badness’ in this scenario quickly becomes liberating, a breach of contract, which allows the question of integrity to centre on the state of the art form itself. The backdrop of Minnis’s unease is poetry as a sphere of undisguised ambition, narcissistic careerism, where people ‘perfect each other’ through congratulatory ‘creative enterprise’. She is intimately acquainted with, and in a sense a product of this world (an Iowa grad), but it’s as if she can’t rely on herself to wear the right face to readings or say the right things in workshop, really participate in the queasy public life of poetry at all – her poetry ‘has to forget about all that’, it has to exorcise it. In doing so, her performances, her petulance, her impatience, become ways to point to the real restrictions. ‘Badness’ becomes the best response to a bad situation; it reinstates the individual perspective by dissociating the poet from a social milieu, a scene, a system of expectations. At the same time, it ensures poems that are unusable for the promotion of poetry as a ‘heritage’ art form. Part of this is made possible by her open countenancing of commercialism, an aspect of poetry that is almost always entirely supressed (: poetry’s non-commerciality is its USP).

Leon’s Hit Wave stages a comparably unholy union of poetry and currency. A companion narrative of sorts to ‘The Torturers’ – a sustained fantasy of the poet’s ascent as a ludicrously powerful and corrupted svengali figure – Hit Wave manufactures a vision of how success as a poet would look and feel, if poetry became seriously interested in money. He begins from this realisation:

The disenfranchised were no longer the heroes of film and literature. The

reflection of extreme wealth replaced every image of beauty…We could either quit or

go commercial.

What follows is a spectacular of debauchery and revenge, riding exuberant success through total collapse and back again as if it were the phasing of the seasons. Boom years are the summers of commerce, and here poetry is just another fertile market, perhaps the most liquid and abstracted of all: success is down to pure manipulation, manoeuvre. ‘Badness’ in Leon is the revelling in his synthetic persona, a diabolical vision where poetry pays in real terms. Again, the serious intent of this is never clear. The hard longing for commerciality as an escape from the impasse of the avant garde can be read perhaps as a rejection of poetry’s fixation with ‘posterity’, the way its ageless concerns are effortlessly accommodated in high art’s buffer zone – in a strange way, poetry’s avowal of its status as non-commodity is required, vouched for, by the demands of mass culture: you can always go to poetry if you need ‘something else’. But this sequence of assumptions leads to an impossible predicament, and both poets know it. This is what the hostility and hopelessness of their poetry manages to express. It would be understandable to question the validity of this, if the states they describe – loss of authentic expression, joyless and enervated wrangling with commodities, disorientation when faced with values ‘unstuck’ from objects, and most urgently, the attempt to locate power, to force it to materialise, by provocation or mastery – were not so clearly the circumstances shared by every subject under capital. Like Seidel, their poems are built of the vestiges of trauma – they are, as it were, made divisible by it – the situation is merely intensified by dramatizing, desperately, the production of poetry itself (: a non-monetary value). If anything, their closest correspondents might be found in the barbed epigrams and grand satires of Roman lyricists: casting a despairing eye over the mouldering riches of an empire on the cusp of decline. Perhaps their ‘reluctance’ is a kind of necessary, willed innocence.

Back at 30,000 feet, while the fuckers at easyJet never did pay back my fee, it was a little like poetry had compensated me in another way. It had offered a strategy – navigation for the flight of my initials, demonstrably and legally incomplete, as they bounced between the proper nouns of companies and cities. I hated it, and for a moment that was music. Art is redemptive. But it is only redeemable in the present.

Texts:

Sam Riviere is the author of Kim Kardashian’s Marriage (Faber & Faber, 2015).