Brian Eno has always got an angle, and more often than not it’s obtuse. His tangential sonic adventures have only ever added to his mystique, and though he’d probably like to think of himself as a perennial provocateur, he’s inescapably a national treasure. That other enfant terrible uncomfortable with yet embraced by the establishment, Grayson Perry in his book Playing To The Gallery recounts a moment in 1996 when Eno had become upset by the normalisation of radical artwork and decided on not so much a dirty protest as a wet one by urinating on one of the many manifestations of Marcel Duchamp’s urinal Fountain. As with much of Eno’s work, this art attack seems at first glance a simple idea, and yet took some ingenuity and lateral thinking. Eno had to surreptitiously rig up a device in the Museum of Modern Art including rubber piping and a pre-emptied bladder in a plastic bag. When quizzed on his actions Eno simply said, "Since de-commodification was one of the buzz words of the day, I described my action as re-commode-ification".

Eno was very much instated into an uber-cerebral world of art installations at the time; it seemed the perfect world into which to attach his contrarian deconstructionist approaches. Now some of these 90s works that are being reissued, with extra tracks. You could say they themselves, ideas or entities, which would not normally be considered goods have been re-commodified. The four albums, Nerve Net, The Shutov Assembly, Neroli and The Drop cover a artistically fecund period from 1992 – 1997 that cover the gamut of Eno’s dynamics – broken pop songs, ambient drones, barely moving immersive experiences and sinister and intricate scores. Three of these albums have been re-pressed onto vinyl, but fear not, Eno’s principles will never be bought like a Klimt or a Koons in a oligarch’s castle, the reissue of Neroli, a solid hour of music in one movement would not be broken "due to the artist’s wish not to break up the music with side splits".

When interviewed at the time of 1992’s Nerve Net, Eno claimed his favourite word was the onomatopoeically delicious "squelchy". The Nerve Net reissue features a highlight of these reissues, a holy grail for completists, the record My Squelchy Life, which had been due for release in 1991 but withdrawn, shelved and mythologized until now. The title track is how I imagine The Pink Panther might have been scored if Henry Mancini lived in Sheffield. ‘Tutti Forgetti’ shows his pleasing intransigence can be counterpointed by intrinsic humour with spoken lyrics such as "I forgot my preferences, I forgot my friends, I forgot my ambulance, I forgot any details pertaining to me or my person or any details or extension thereof, or any proposed details or extensions thereof". I can’t imagine Eno forgetting anything despite his multifarious musical personalities.

The understated, classically arranged track ‘Some Words’ asks "what channel are you on?" and Eno’s is constantly retuning. Much of Nerve Net and My Squelchy Life actually features discernible songs, and vocals including those of Robert Fripp. The song ‘I Fall Up’ originally on the Ali Click EP and rejected from the shelved My Squelchy Life, features the line "I’m cackling off from the Congo. I’m stuck in a big fat watermelon" and sits in the juncture between 1981 Eno’s album with David Byrne My Life In The Bush Of The Ghosts and Byrne’s later Luaka Bop led ethic excursions. Another real highlight is ‘The Harness’ – a real pop gem, like Duran Duran’s ‘Something I Should Know’ played at the wrong speed, yet less wild boyz, more grizzled glamour. Eno had previously been working with John Cale on the record Wrong Way Up, but he had certainly got his pop chops looking ship shape for My Squelchy Life. A real shame that it’s only emerged wide eyed from the bootleg now, but worth savouring for that reason, and timeless nonetheless.

A record in which time literally stops still is 1993’s Neroli (Thinking Music Part IV), a record remarkable in its restraint and yet ambitious in its scale, here combined with a previously unreleased and more defined drone called ‘New Space Music’. The construction of Neroli is repetitious and yet the joins are barely discernible. It’s named after an aromatherapy scent derived from a Seville orange, whose characteristics much like the record describes are sweet, honeyed and somewhat metallic. Certainly metallic in construction, but organic in feeling, this expression of Eno’s mood music was so enveloping and warmly embracing that it has reputedly been implemented as maternity ward music. If Eno wanted it to be rewarding not demanding, it does that with deft aptitude, and disciplined design. Single notes ring out, in a harmonic ebb and flow like amniotic fluid around new pulsing life. If there’s one born every minute, Eno comes but once in a lifetime. And this is a sloping loop that could last a lifetime, if he’d let it.

Eno once gave a newsreader like lecture called Perfume, Defence & David Bowie’s Wedding. Always a great talker, full of sound bites and biting cynicism, he is perhaps the ultimate salesperson. For his self, for his sonic wares, for a certain lifestyle. Neroli is ultimately a perfume, and an essential and oily performance. What commodities sell a lifestyle these days better than the profligacy of perfume adverts that constantly pervade our screens at this time of year?

Much as Eno talks a good game, what he really thinks of the game of commercial music itself is often hard to keep track of. Tellingly, the sleeve notes to Nerve Net give us a snapshot. It contains a missive written after a marketing meeting at Warner Brothers prior to its release. When discussing how the record might be promoted Eno wrote, "Why do people buy a particular record? It might be: 1) because they heard it on the radio and they like it, or 2) because they believe that this ought to be part of their lifestyle. Of course, these are always intertwined, but a lot of promotion only concerns itself with their objective of making sure people get to know the record’s out and hear the music on the radio in the hope they’ll be seduced into buying it. This is of course essential, but I think in my case it is of limited value unless it goes hand in hand with a style-defining approach…" the concepts that we hear through".

Even now, Eno’s not tired of defining himself by a concept. He’s had a busy year, his second album with Karl Hyde The High Life was completely freewheeling around the ideas of cities built on hills. 1992’s The Shutov Assembly was based around his friend, the Russian artist Sergei Shutov. Shutov used to paint to Eno’s work but the flow of it was stemmed by the Iron Curtain. Eno consequently assembled a tape of previously unreleased compositions to send to Russia with love. While doing this he found a way to make a complete suite of music that could accompany your centenary, biennale, triennial. It’s art installation music that will hang in the air of the white space galleries as long as the Mona Lisa disguises her less than sanguine smile in the Louvre. It’s the music to collect Jeff Koons to, or perhaps lose your Elgin marbles while transfixed by a luminous light box.

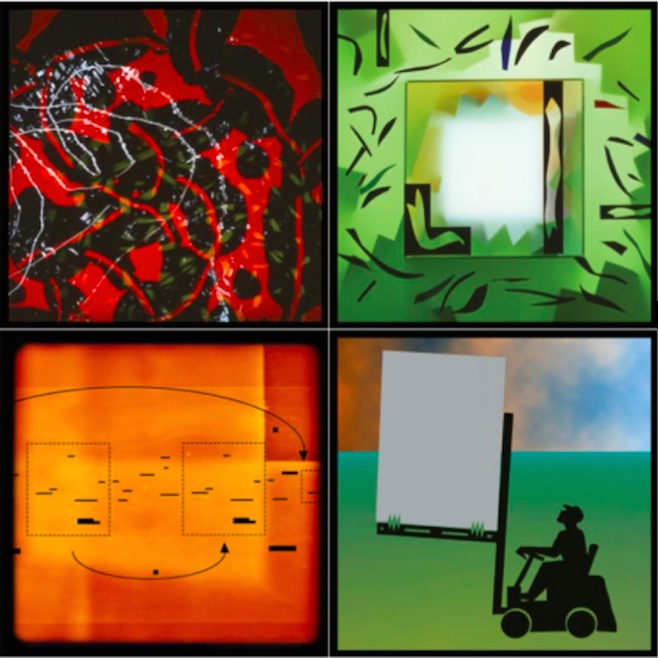

The last of the tetraptych of Eno’s tangential reissues is 1997’s The Drop. Never knowingly undersold he likens the album to Ben-Hur and himself to Cecil B. DeMille of the modern LP, and goes onto explore a new style of sound that he has invented and named Drop Music. It’s jazz, but more alien than free, melodious but multi directional. He’s divined the polyrhythmic free flow of Fela Kuti, whose own retrospective Eno curated this year, and he’s fused the lesser known but no less complex Mahavishnu Orchestra to make something intoxicating and whisper it, danceable in the case of bonus track ‘Never Stomp’. This track and those that follow were originally a part of 77 Million – An Audio Visual Installation but it is now a crazy legged addition to The Drop.

The original art installation much like The Drop‘s musical flit and foray featured an ever-evolving audio-visual kaleidoscope algorhythmically produced in a New York gallery – quite literally 77 Million Paintings. They never settled in the same place for long, perhaps a metaphor for Eno’s own work of which this is the mid-term report. They say that Artificial Intelligence will one day destroy mankind, but thankfully no algorhythm can faithfully reproduce Eno’s kind of acute genius.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/16912-brian-eno-nerve-net-the-shutov-assembly-neroli-the-drop-review” data-width="550">