Born in Birmingham in 1969, Adam Nevill has spent the last ten years crafting some of the most powerfully imaginative and original horror novels this country has ever produced. When I first discovered his work last year, I ended up reading his six novels back to back in as many months. 2012’s Last Days was the first one I picked up and it hooked me instantly, with its combination of cult/occult psychology and guerilla filmmaking point of view, and its unnerving portrayal of an insidious and ancient evil. The fact that Nevill had clearly based his ‘Temple of the Last Days’ on the real life Process Church of the Final Judgement and more specifically Timothy Wyllie’s excellent 2009 book about the cult, Love Sex Fear Death, combined with a use of language that made for compulsive reading without any loss of literary quality, made it an instant hit for me. I read the others in rapid succession and was unsurprised to learn that several had already had their film rights optioned. The ending to 2011’s The Ritual, in which four old college friends are stalked through the Scandinavian wilderness by a an ancient Goat of Mendes style creature, had my heart palpitating so wildly on the upper deck of a London bus it was all I could do not to shout out “Kill it, kill it!” as the protagonist finally faced the monster head on. The unpleasant psychological after effects of 2010’s Apartment 16, Nevill’s outsider novel, in which the lingering presence of an obscure and evil artist (inspired in some sense by Francis Bacon) infects the apartment block in which he lived, remained long after I’d turned the last page. 2013’s House of Small Shadows, perhaps the most frightening, and certainly the weirdest of all Nevill’s books, likewise left many indelible images in its wake; its dreamlike intensity refusing to be reduced to any singular narrative explanation.

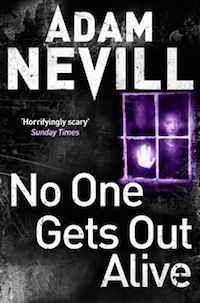

His latest book, No One Gets Out Alive, which was released last month, is a compulsively-readable examination of the treatment of the female victim in the horror genre, as well as an analysis of the media’s obsession with human evil and ultimately, a disturbing depiction of a folkloric, totemic deeper darkness transcending individual lifetimes. Like all of Nevill’s books, it hooks the reader quickly and doesn’t let go until the ending, which as usual does not disappoint. A valid claim often made about horror fiction is that the scares are usually over by the time the reveal comes, but Nevill never really lets up the tension and the precise details of the horror, when they do arrive, are often vividly disturbing in their effects. Nevill also has a clearly-developed philosophical and moral sensibility, as well as a sense of humour, as evidenced by his dedication of the novel to his young daughter with the proviso: “One day your old Dad is going to have a lot of explaining to do about these books.”

You’ve described your latest novel as a “riff on horror films and victims (or an attempted re-empowerment of such)” as well as dealing with “the dismal, bestial, banal and grubby nature of most killers and their enslavement to lower brain function”: is this an idea that’s been germinating for some time? Clearly there is a need to move beyond the traditionally two-dimensional notion of the female as victim in cinematic and televisual horror.

Adam Nevill: I’ve read quite a bit of investigative journalism and quality true crime writing, in the course of research for various books, to try and establish for myself what actually happened in certain notorious and “celebrated” events, as well as to determine as much as I can about the individuals who have attained a kind of cultish folk history around themselves – Jim Jones, Charles Manson, various serial killers etc. Now, the true nature of these episodes and individuals is often concealed by interpretations and imaginative re-inventions, and yet, the truth is often disappointingly banal. Even though I deal with the supernormal and unworldly, the human elements in my books are based on as authentic a psychology as I can suggest. And over and over again I find the same unscrupulous, reptile-brained intelligences, hidden beneath a superficial charisma, and feeding upon the trusting, the naïve and the vulnerable.

I have a kind of appalled curiosity about certain personality types – particularly the narcissistic variety – and I like to drill down and demystify them, even unman them in fiction, and explore the supernormal quality that seems to endure around their reputations. It’s interesting how some psychologists are even suggesting new interpretations of how civilisation and modern society has developed, with an emphasis on game-changing psychopaths who have, at times, changed history. I think there’s never been a better time to reappraise the “talent”, the game-changers, the great figures of the past, the idea of leadership and hierarchy of which we are all still sublimated – in whose images and systems do we now live? In my own little corner of the vast spider’s web, I try to explore that.

As regards the second part of the question, I think horror film and television is the most dominant form in horror culture, and has been for a long time now. I can’t see it being supplanted. So I do feed off it for my own fiction, and am inspired by horror in visual mediums. Some of the new dramas are sublime. A great deal of horror film making is mediocre, and the true horror of being a victim is often lost by an eternity of disposable characters onscreen – the nature of their ends is greater than who they were. And yet when we consider the plague of rape, enslavement, repression and domestic violence that women are still subjected to, then the screaming hotties in denim shorts, who are chased and dispatched by “anti-heroes”, offer no insight into anything but morbid physical butchery. Where fiction has an advantage is in an exploration of the inner lives of characters, particularly of victims. I’m always pleased when readers remark that my books get under their skin, or are memorably disturbing, and I think it might be because I try and accurately depict the experience of being in terrible situations, tormented and savaged by the worst kind of people. I split the emphasis between the tormented and the tormentors, but give the victim the point of view.

You’ve previously stated that the research you did for No One Gets Out Alive took you to places that you wouldn’t care to revisit in a hurry. Having looked at some of that kind of material myself, it seems apparent that people like Jeffrey Dahmer and Fred West act out very strong psychological impulses to do the awful things they do. I’m not attempting to excuse their actions but it does seem that they are broken machines. If you accept that premise, do you believe that there may be another kind of person who commits evil acts consciously?

AN: The malignant narcissism at the root of so many high profile killers, cult leaders, dictators, is twinned with an absence of a conscience – that is the whole point of them and their great advantage over us: there is no guilt or remorse, just a single-minded indulgence of hardwired impulses, so their actions are deliberate, and rational to them, but unfettered by any circuit breakers. This can manifest as a desire to be empowered through cruelty and the suffering of others. I think there is a vicarious fascination with the “alien” amongst us. The behavior of the psychopath is most often bloodless, though, and is enacted in the workplace, the home, the ranks of the military and so forth. From what I have read in neuroscience and forensic psychiatry there does appear to be evidence of brain malformation in those who have narcissistic personality disorders. Some tests on psychopaths in prison were outlawed for being inhumane – their reactions to death and suffering were abnormal, unemotional and yet full of fascination as if they were figuring out puzzles. I was quite surprised to read that even the NHS lists one in a hundred people as suffering from narcissistic personality disorders, but there also seems to be a sliding scale, and very few would kill. I think I have encountered the lesser psychopath at least five times, that performs unconscionable acts without restraint in the workplace, and in relationships, but could be fiercely loving to their own family members, while everyone else was, literally, there to be used no matter the consequences for the ill used. They were all habitual liars, indulged in fraud, while possessing a superhuman self-belief that involved immediate self-justification. But that kind of narcissist, who forms the majority, are a long way distant from a Fred West, mercifully, who was a very rare case.

I think doing evil is always conscious. Even respectable, ordinary people are often fully aware of their own monstrousness, but they are able to function because they never have to observe anything but statistics. They don’t see. It’s human to wish the worst for your enemies or opponents, but to actually watch them suffer, and derive satisfaction from it, is something altogether different. Few well-adjusted people would pass that test, and let’s be thankful that most of us are aligned with ideas of fairness, compassion and forgiveness. What I often suggest in my books is that it is being humane that makes us the perfect and natural victims of those that lack a conscience. It’s a horrible idea, but I think it’s been true throughout the entire history of civilisation and is no less true today. Are one in a hundred people seriously lacking in that much empathy and creating misery in those around them today? Hell truly is other people in that case and we can’t escape them. Call them Legion for they are many.

The later part of the book deals specifically with the nature of the media and how they deal with such material. Do you feel that the media is in some way complicit in the ‘evil’ (as they would see it) acts that they dwell upon? There is often an almost palpable sense of glee emanating from such stories.

AN: I’m interested in the media’s perceptions and interpretations, and of cult material, and that really started appearing as an idea in Last Days. And of course the real media is deliberately irresponsible and feckless, by ramping up sensation to sell a product, to get ratings. I am not sure I would call that evil, unless it was propaganda to serve disingenuous interests. A recent example of sensationalising real news was the media’s early coverage of IS – as heinous as their crimes are and continue to be, the media continually presented them as very dynamic and visual and larger than life by using the organisation’s own propaganda tapes, and vision of themselves – bearded warrior monks, freedom fighters etc. with a kind of Che chic (and then wondered why so many of the disaffected, naïve, ill-informed, and perhaps sadistic, went and joined the Caliphate).

But I really enjoy creating true crime case histories and ‘mythic pop’ culture around the events in my own books, that reflect upon how the real world media machine works. My invented pop culture often functions like our media and only the lead character and reader are privy to the truth beneath the interpretations. I’d hope my books aren’t perceived as feeding the glamour of cult leaders and psychopaths, or even detracting from what they are actually like, or what their victim’s suffer. In fact, I sometimes go to great lengths to nail how insidious it all is, and my stories are often informed by true case histories.

As someone who still works in the publishing industry in addition to being a novelist, how do you think reading habits are changing? And is it still possible to make a living just writing novels?

AN: I think digital publishing has made books too disposable and devalued books and writing. They’re going the way of MP3 files – people download hundreds or even thousands of books for peanuts, or for free, and never read them or bin them after one page if they are not gripped. Many books deserve more. I still think books are such an important part of culture and of civilisaton, so it’s odd that we’ll throw something so significant into this kind of tech-led disruption without any idea of the endgame, or any regulation.

I’d say it’s increasingly hard for anyone who is not a big front list writer to make a living writing novels. Just look at the business model now – ebooks are 40% of sales but the ideal price of an ebook is 99p. Only a few years ago nearly all books were either £18 hardbacks or £7 to £8 paperbacks. I think writers’ incomes have fallen roughly in line with that devaluing. But it’s good for the consumer so nothing else matters. Even though I could have been a full time writer since 2009, I’ve kept working because of my family’s security that I always weigh against the increasing insecurity of being a professional writer. Combine this drop in value with digital piracy and the discoverability hell created by self-publishing and the zillions of new imprints, as well as huge back catalogues being uploaded. How the hell does anyone find anything, or know what is being published? It’s the same with films too now that digital technology has democratised filmmaking. I find myself increasingly reliant on people who share similar tastes, who keep their eyes open, and filter things that I may be interested in.

I understand that when you were pitching The Ritual, you were told not to bother as men weren’t a significant enough demographic in terms of reading novels anymore! I imagine this only strengthened your resolve?

AN: No, when working as a commissioning editor, I was told in a publishing meeting not to bring any more books into meetings for consideration that were not aimed at female readers, their aspirations and lifestyles because “men don’t read anymore”. And I was the editor of fiction in a company being moved in a popular, non-fiction editorial direction. How could a general publisher just rule out half the population of the planet? Partly because of that incident I wrote a book about men, and one I hoped young men with little experience of adult reading, would enjoy. I tried to tap into what thrilled me as a younger reader. I also thought there is an oversimplification of men afoot in the media – the dufus husband watching footie in nearly every commercial with a domestic setting, the Nuts and Zoo lad, the man’s man, the hero, the pass or fail in a life assessment on material achievements, etc. I asked myself questions about my own generation, its aspirations, expectations, how we measure against perceptions of the baby boomer and our grandparents’ generations.

The Guardian has described you as being “Britain’s answer to Stephen King,” how do you feel about that? I love Stephen King but I think you two are obviously very different sorts of writers. Are you a fan and do you still read his books?

AN: There’s a temptation to be flattered, but there’s an overriding sobriety about scale. I never thought the comparison was fair to Stephen King. But horror comparisons come as a bi-product of his monumental success – much of which may not have even been processed yet. And such a force he continues to be in popular culture, I suspect he has even shaped how the modern popular novel is now written. Is there any equivalency between us on sales, foreign translations, film adaptations, readership? No. I think the only real comparison is that I share his love of horror.

There has actually been, from a UK publisher’s point of view, very little room left in publishing for any horror but that of King, Herbert, Koontz, Barker, Rice et al, for years now, so a whole generation of mainstream readers and critics can only measure those of us who have recently crept out of the abyss against writers who have been going strong since the seventies. He’s the head of the family, the Lucifer, and we’re the winged minions trying to get airborne, and I don’t know of any horror writers that don’t respect him. He’s influenced and delighted most of us – for me it was Misery, Pet Sematary, The Shining and Carrie – and he’s probably had a hand in making most of us want (or try) to write. So, yes, I am a huge fan but don’t take the comparison seriously. I think what the reviewer was actually saying is that I am a British horror writer who might get noticed and stick around for a bit. And that’s not something I take for granted.

What are your own personal literary influences? I know you have already said to me that you feel more influenced by dark literary fiction rather than just horror and that you feel this is “already starting to pay dividends.” What do you feel about the current state of the horror genre?

AN: I have a huge range of influences from the canon of the supernatural in fiction – James, Machen, Blackwood, Onions, De la Mare, Wharton, Wakefield and many others, to the moderns like Campbell, Hill, Aickman, Barker, Highsmith – but the impetus to actually start writing came to me through the modernists and outsiders as much as it did through horror writers, chiefly James Joyce, Dostoyevsky, Hesse, Hamsun, Colin Wilson, Fante. I’ve been a big reader of twentieth-century literary or post-modern fiction since my teens and have been inspired by more authors than I can possibly mention here. And I discover new influences all the time. American crime writers like James Ellroy have had a big impact on me, as have regional literary and noir writers like Woodrell, William Gay, Donald Ray Pollock, Cormac McCarthy. It’s enormously useful to read as widely as possible, good writers, classic and modern, to learn about voice, and narrative techniques, and to just see what can be done with fiction, what form it can take. Horror can appear in so many forms and needn’t be confined by narrow, conservative expectations.

The shelves of high street bookshops may not reflect it, but modern horror and weird fiction is enjoying a real renaissance right now. The quality of so much new fiction has not stopped surprising me since around 2004, and most of it is coming from the small presses. There’s a new wave of more literary horror being written and published in the US, that embraces the unique visions of Poe, Lovecraft and Ligotti, but it’s also vital in its own right and is moving horror forward in really interesting, speculative and idiosyncratic ways. The same can be said of the UK in its own way. There is such a variety now, from the traditional spectre subgenres, to speculative fiction, supernatural horror, crossovers with crime. It’s a great time to be a reader of horror.

Are there horror films that offend you in the wrong way?

AN: Horror filmmaking has always been both prolific and uneven, I think. Some ideas, a few set-pieces, the imagery, an atmosphere, an indefinable sense of the “other”, or a performance can be sublime in an otherwise poor film. It’s hard to get everything right over an entire movie. The only films that tend to make me want to put my foot through the screen are the bigger budget films that get theatrical releases, and that are pretty good for at least one half of the film, before degenerating into the juvenile to score cheap scares and thrills. Mama and The Conjuring are the best recent examples I can give. Afraid I didn’t like You’re Next at all. I tend to look out for the new films that, to my tastes and temperament, are special. Sleep Tight, Absentia, Lovely Molly, The Pact, Evil Rising, Mr Jones, Borderlands, V/H/S 2, Kill List, Devoured, Lake Mungo and Snowtown are all recent films that will join my inner sanctum of favourite horror films. Tying in with the new waves of quality horror writers, the makers of intelligent and affecting horror films are on fire right now too. I honestly feel spoiled and excited about what is coming out.

I know a lot of people found the end of True Detective to be hugely disappointing, although personally I loved it from start to finish. It occurred to me that perhaps, for those who were primarily crime/detective fiction fans the end was disappointing because it broke with the rules of that genre, whereas for viewers who were primarily horror fans, it was a great ending because it managed to flaunt one of the real problems with the horror genre – i.e. the monster not being scary anymore after it has been revealed. Do you have any thoughts on this and do you think the divide between the two reactions says anything about the future of elements of the horror genre appearing in mainstream drama/fiction?

AN: I enjoyed it for all the same reasons I enjoy American noir crime writing, regional American literary fiction, and the modern North American weird tale that is entwined with Thomas Ligotti’s legacy. TD was so literary, from the script, to the ideas, to the characters, and was written by a prose writer who “gets” all the literary conventions I mention above. I honestly felt it had been made for me. And it was made for adults – at no point did I feel it was sliding towards “a wider share of a younger mainstream audience”. I am afraid I will not criticize it. How often does horror get that kind of treatment in a television series, and achieve the same intensity and effects? Rarely, I’d say. As for horror on TV, there seems to be no end to it now, but I am not complaining, I am luxuriating. I think Hannibal is excellent, and I have enjoyed American Horror Story too for its imagery and narrative skill and ideas, even if I struggle to care as I am watching. It’s like a soap opera combined with expressionism, and it somehow works. I’m also impressed by Intruders and enjoyed some of The Returned. I haven’t even watched The Walking Dead or Bates Motel yet – I can’t keep up and I am a lifelong devotee of horror.

Finally, I understand that you have hinted that your next work will concern ‘the horror of the future as opposed to the past.’ Can you give us even a tiny bit more of a hint than that?

AN: Yes, I actually delivered my next novel this week. And it is a distillation of three of my greatest imagined horrors – the loss of a child, runaway climate change, and the collapse of civilisation into barbarism. It is still supernatural horror though, and has some of my hardboiled and noir influences seeping through.

No One Gets Out Alive is out now, published by Pan MacMillan