"I stood here, and saw before me the unutterable, the unthinkable gulf that yawns profound between two worlds, the world of matter and the world of spirit; I saw the great empty deep stretch dim before me, and in that instant a bridge of light leapt from the earth to the unknown shore, and the abyss was spanned." – Dr. Raymond in The Great God Pan

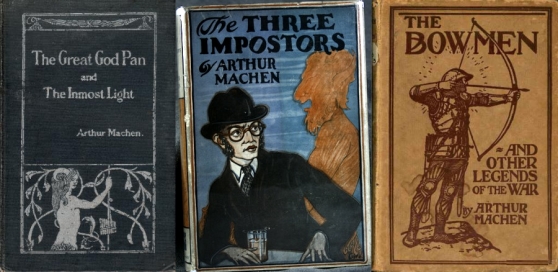

When an author’s muse was ‘the unutterable’, perhaps it’s best to begin with what you wouldn’t say about him. Arthur Machen’s stories are often labelled ‘supernatural horror’, but you won’t find ghosts, demons or vampires therein. He found success competing with the blockbuster myths of his day (Sherlock Holmes, Dorian Gray, Jeckyll and Hyde) but the corruption and licentiousness he revealed came from old, wild ways rather than decadent modernity. He had a succès de scandale in a Beardsley-designed jacket but recoiled from fin de siècle excess. He dallied with occultist societies but remained a devout Christian. In the canon of weird fiction he’s placed somewhere between the macabre investigations of Edgar Allan Poe and the bombastic irruptions of H.P. Lovecraft. But their explicable styles don’t hint at the ineffable Machen hit, as difficult to shake as it is to pinpoint.

Take a typical tale: _The Red Hand_, from 1895. The mercurial Dyson and rationalist Phillipps debate the prospect that troglodyte man walks among them in the streets of London. They step out for an evening stroll and drift into an obscure region of town, where they stumble across a murder victim. There’s a primitive flint knife near the scene and ‘a few rude marks, done in red chalk’ on the wall. A cryptic, hand-written note and a drunken woman in a Gray’s Inn Road pub soon deepen the mystery. Dyson’s ‘theory of improbability’, literary aptitude and walker’s knowledge of the city lead him to the obscene truth – an unfathomable horror that leaves our intuitive and intellectual interlocutors alike high and dry.

Machen’s style was a kind of pulp realism lit up by lyrical visions and violent revelations. As such, his London is still one of the best you’ll read. As much as the capital’s ugliness and monotony horrified him, he was enchanted by its sublime scale and abundant distractions. The characters’ concerns (money and accommodation troubles, wishing they could spend more time on amateur interests), pleasures (red wine, good reading) and idle debates (about scientific discoveries, unsolved crimes) feel familiar today. Still more so, the city itself: the interminable North London streets they pace, and the sudden shifts in psychological temperature around each corner. But the real Machen magic happens when he hints at the numinous, just when you’re least expecting it. As Dyson and Phillipps, that evening, ‘passed along a flaring causeway they could hear at intervals between the clamour of the children and triumphant Gloria played on a piano-organ the long deep hum and roll of the traffic in Holborn, a sound so persistent that it echoed like the turning of everlasting wheels.’

These peeks behind the veil of everyday reality run through the best Machen stories, like those in his tour de force _The Three Impostors_. In it, Dyson and Phillipps traverse a city of immanent, seedy strangeness, stumbling across tales that link distant weird happenings to the room they sit in or the street they’ve wandered onto. They’re relayed by various characters and correspondents, in a ‘Chinese box’ structure (inspired by Robert Louis Stevenson’s More New Arabian Nights: The Dynamiter). Two of his greatest hits are in there: the widely anthologised ‘novels’ of The Black Seal – which inspired some of H.P. Lovecraft’s best-known stories – and The White Powder, a demented tale of prescription drug hell (a favourite of Mick Jagger’s). Piercing imagery, tangible city life and a gentle hedonism rub up against occasional plot creaks and clunky prose tics, producing a madcap energy and sense of disorientation apt to the great metropolis. For all their pulp contingency, Machen’s erudite characters would run rings around, say, Ian McEwan’s slowcoach Londoners when discussing rationality. Their nuanced positions linger on in the face of the stories’ mysterious transgressions, which stick you like a knife. It’s easy to see why both Borges and Conan Doyle were fans.

When Machen’s fiction leaves the capital it usually heads for his home town of Caerleon, South Wales: a place of blinding natural beauty and putrid, hidden sex and violence. Its ruined Roman amphitheatre is put to foul and incandescent use in _The Shining Pyramid, after Vaughan the spooked city exile calls Dyson in to help investigate some strangely arranged flints that are freaking him out. The green mountains are also the setting for the brain operation that unleashes so much calamity in The Great God Pan. But it’s The White People_ that invokes Machen’s wild West most vividly. After a sharp dialogue in London about paradoxes of evil and sin, we’re thrown into a powerfully lucid account of unclear goings-on in the countryside, written by a 14-year-old girl. It’s a mesmerising piece of literary ventriloquism, packed with psychological and sensory fireworks; a first-person, present tense fantasia that offers no familiar props with which to steady yourself. It’s weird, and its tang was so credible that people assumed it was rooted in Welsh folklore or occult practices. But, as always, Machen had made it all up.

His relationship with the occult has long been the subject of speculation and wish-fulfilment, mainly due to a brief sojourn with the infamous Golden Dawn. It’s worth bearing in mind that half of Europe’s progressive arty types passed through similar societies at the time, hoping to join other outsiders in studying symbols, distant cultures and unmapped experiences. But Machen wrote these tales years before he joined, and even while a member would dismiss "such impostures as spiritualism or theosophy". He seems to have found the door sharpish after a young Aleister Crowley merked both his good friend A.E. Waite (for his ‘pedantry’) and W.B. Yeats (who’d assured Crowley his poetry was atrocious, just not in the sense he was aiming for).

A quick look at the Golden Dawn’s schtick is enough to dispel any parallels with Machen’s fiction. They’d draw mind-numbingly elaborate pseudoscientific connections between unrelated historic cults, aiming (and claiming) to gain control over physical reality, other people’s thoughts, and so on. Machen’s tales are anathema to all that – his unknown unknowns fell any fantasies of certainty or control. The quality he calls ‘the unutterable’ or ‘the ineffable’ seeps in mid-stroll, then snaps you back to the quotidian before you can register what’s happened. You sense that the author is a fairly conventional man of letters who can’t quite work out where where all this discomfiting oddness is coming from.

It’s possible that a short job cataloguing esoteric books in 1885 gave Machen a dilettante’s taste for the strange language and tantalising ideas that pop up across strands of folklore, philosophy and theology tied together by occultists. But in his nineteenth century tales, well, one character keeps occult reading in his drawer, some passages and titles (The Transmutations, _The Inmost Light_) seem touched by the poetics of alchemy – but that’s about all the ‘real’ esoterica you’ll find. While the influence of his beloved Romantics and bestselling contemporaries was clear – not least because he had a habit of naming them mid-influence – Arthur Machen’s mysteries were unique. Today he appears alongside Harry Secombe on lists of notable Welsh Anglicans.

Machen’s real magic was language: he thought literature should induce ‘ecstasy’ and would work his words until they took on a musical ring. Or at least, he would when he could afford to. His fortunes varied wildly, and success and notoriety proved inseparable. Early on, the St James Gazette sacked him because readers found one of his tales too dark; Oscar Wilde was sufficiently impressed to invite him out for a chat about absinthe. Then The Great God Pan became a runaway hit after the Manchester Guardian called it "The most acutely and intentionally disagreeable book yet seen in English." Along with Aubrey Beardsley’s sensational cover art, this amounted to an association with the decadents that would make Machen unpublishable following Wilde’s scandalous trial in 1895. During the lean years that ensued, he worked as a touring actor and eventually became a reluctant fixture on Fleet Street.

In the new century Machen tried his hand at longer works and different styles. The results were often dire (like the almost surreally boring exercise in realism, A Fragment of Life: an aging couple moves to the countryside, slowly) but he watched his myths take off big time. Pan began to appear in less concupiscent forms: J.M. Barrie’s Peter, and the psychedelic Piper at the Gates of Dawn in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. Machen pushed the story of the Holy Grail, in his journalism and the popular tale The Great Return (which, like his other Christian stories, leaves me as cold as any church service). It soon became integral to modernist works like T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and Mary Butts’ Armed With Madness, and later on Indiana Jones and Dan Brown. Writing both fiction and reportage with the same byline backfired spectacularly in the early days of World War One, when people refused to believe that The Bowmen, Machen’s tale of supernatural intervention on the battlefield, wasn’t fact. The Angel of Mons legend was born, as was his biggest hit of the century, for which it seems he wasn’t paid royalties.

Still, when Machen returned to the weird tale proper he did so in style. Out of the Earth added reportage to his repertoire, exploiting both wartime confusion and the perpetual British fear of feral youth. His yarns took on a harder edge, nowhere more so than in his late peak _The Terror_. It opens with a new unutterable – wartime secrets that sink any publication which alludes to them – and soon trails a concatenation of inexplicable horrors across the British Isles. A neat-freak’s nightmare of real contemporary terror (the new killing machines), paranoid hypotheses (like a ‘Z-Ray’ that controls people’s behaviour through the ‘psychic aether’), regional caricatures and reactionary asides, it’s also a relentlessly compelling ride that includes some of Machen’s most idiosyncratically beautiful writing. The roaming titular terror is as sensually immediate and overwhelming as any of his creations, and the journal account from a dead painter as heady.

Machen was still widely read in Corgi and Panther anthologies through the Sixties and Seventies, and has been kept in print by horror and budget presses since. However, his influence on other writers and directors remains suitably veiled. Nods from John Carpenter (look out for Mr Machen in The Fog), Stephen King and others have confirmed his place in the horror canon, no doubt underwritten by H.P. Lovecraft’s praise in his essay Supernatural Horror in Literature. But you’d struggle to find artists in any medium who could be described as ‘Machenesque’; a namedrop of Pan (as with Guillermo Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth) is as close as they tend to tread. If you squint, you might see parallels in the works of Machen’s familial descendents: in Lolly Willowes, a modern take on witchcraft by his step-niece Sylvia Townsend Warner; or in visual artist Tessa Farmer‘s little people.

In recent years a fuzzy image of Machen the occultish visionary has lingered in the margins of pop culture. Current 93’s The Inmost Light, the finest illumination of their bloody cosmology, takes its title (but little else) from Machen’s Harlesden-set horror. And in the phantasmagoric Snakes and Ladders Alan Moore summoned a biographical travesty of ‘magick’ Machen, in the name of that nebulous notion, ‘psychogeography’. Now, Machen would surely have derided talk of dérives (just as he dismissed psychoanalysis when that turned up). But to my mind the P-word would at least suit his imaginative fiction – in which psychological states and physical surroundings are inseparable, and charged discoveries made through drifting – better than it does the flat non-fiction peddled by today’s urban(e) local history enthusiasts. Machen reminisces about his taste for the city wander in the introduction to _House of Souls; intoxicates with his visions of Caerleon and the capital in his coming-of-age novel The Hill of Dreams_; and throws seasoned Londoners’ perceptions of the city in the late story N.

One Machen fan managed to pay tribute while creating something comparable in a new medium. Mark E. Smith has hinted at what he admires most about these tales: “The real occult’s in the pubs of the East End. In the stinking boats of the Thames, not in Egypt. It’s on your doorstep basically." And as fans know, many of the strongest Fall songs, from ‘Psykick Dance Hall’ to ‘Sparta FC’, have the weird and ancient permate the mundane present. While Smith regularly chucks in scraps from across his personal canon of modernist and pulp writers, oblique tributes to Machen abound. The ‘City Hobgoblins’ – “Evil émigrés from old green glades”; “Ten times my age / One-tenth my height” – bear more than a passing resemblance to the ‘stunted, childlike forms with ancient, depraved faces’ Machen leads us to in wild Wales. Then there’s The Unutterable, the character Roman Totale XVII (‘the bastard offspring of Charles I and the Great God Pan’), and the sleeve credits for Dragnet, which claim the recordings are the result of an experiment in the remote Welsh mountains.

Most of all, though, ‘Leave The Capitol’, is Machen to the core. The title alone evokes the flight from London that runs through his fiction, and the era of the Caerleon fortress (that Roman, authoritarian ‘Capitol’). The song itself gives you: ‘Pan resides in Welsh green masquerades’ (as he does in The Great God Pan); a “vaudeville pub back room”, “music teachers” and “I live with cancer death wife” (Machen’s first wife, Amy Hogg, was a music teacher who worked in the theatre, and died young of cancer); “One room” (The Hill of Dreams finds a skint Lucien living in one tiny London room, ‘much smaller than any monastic “cell” that I have seen’, and drifting into visions of the Roman ruins when he’s trying to write). “I laughed at the Great God, Pan” actually references a Jack Kirby comic strip, which . . . I could go on, but some things are better left unspoken.

Essential Arthur Machen

The White People and Other Weird Stories, the first Machen anthology from a major publisher in decades, is out now on Penguin. It includes many of his best-loved tales, plus a scholarly introduction from S.T. Joshi and a gimlet-eyed foreword by Guillermo Del Toro.

Much of Machen’s work is out of copyright and can be read for free. You can’t go wrong with any of these: The Three Impostors, The Red Hand, The Shining Pyramid, The Great God Pan, The Inmost Light, The White People, The Terror.