There is a moment near the end of JA Baker’s nominally ‘non-fictional’ work The Peregrine where the narrator, tracking the eponymous bird through the Essex landscape, comes cross its latest prey.

I found myself crouching over the kill, like a mantling hawk. My eyes turned quickly about, alert for the walking heads of men.

In the first of these two sentences, Baker is like a hawk. In the second sentence, he has become the bird. This is one of many instances in The Peregrine where the writing attempts to shed its human baggage and transform itself into something wild and primal.

The book is the account of ten years the author spent stalking a peregrine through woodland, fields and estuaries. But this is reality heavily stripped, shorn of days and dates. The passage of time is delineated only in terms which Neolithic man might have understood:

Autumn begins my season of hawk-hunting, spring ends it, and winter glitters between like the arch of Orion.

There are no place names. Only "the South", "the North", "the East" and "the West". Humans appear a few times in the book as mere specks on the horizon, no more significant than a flitting sparrow. Baker eschews any hint of personal biographical detail outside his quest for the peregrine. The result is a mythological landscape where hunter becomes the hunted; man becomes bird. It is closer to being a magical fable than most fiction you will ever read. Yet it is not a novel. Certainly, it’s not considered one.

But why not?

In The Quietus [June 2013] an article by Thomas Brewster called Reality Check: An Encomium for the "Dying" Novel looked at some recent novelists’ attempts to stand aside from conventional forms. He referred to author David Shields’ plea for a merging of fictional and nonfictional writing, and showed how this is manifest in works of Adam Thirlwell, Marie Calloway, Ned Beauman and Ali Smith. Some dissenting comments beneath Brewster’s article complained that literary fiction is too obsessed with form: experimentation for experimentation’s sake, to the point that it shies away from reality, looks inwardly upon itself, obsessed with post-modernist tropes.

I can’t say whether this is true or not. I’m not entirely sure what literary fiction is, or means. Nor do I care for the hierarchy of art implied by the term. What I do know is that there’s a category of work in which the fusion of fictional and non-fictional forms is not an experiment but a fundamental mode of communication: a key to accessing a deeper truth about human existence.

Some of these works are considered novels. Most are considered non-fiction, travel, memoir, art and other categories, sometimes all of them listed on the same back cover, smeared with a publisher’s tears. Some of its modern progenitors – including Iain Sinclair, Laura Oldfield Ford, Robert Macfarlane, JA Baker, WG Sebald, William Least Heat Moon and Bruce Chatwin – habitually fuse fiction and non-fiction, not out of a desire to flex their literary muscles, but in an attempt to express the human experience of place. In their quest to do so, they have less in common with essayists, guide book writers and historians than they do with major novelists like Laurence Sterne, Herman Melville and James Joyce. They grapple with the same problems of truth, narrative subjectivity and the painful distance between language and that which it describes; and they use similar innovations to tackle these problems, including essays, images, lists, found objects, diagrams and spaces for the reader to create their own texts.

As a literary touchstone, let’s take Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, which has the quality of being one of the earliest novels and also one of the earliest experimental novels. The narrator’s aim is to describe a life in full, in every detail, no matter how mundane. Tristram discovers that writing reality isn’t simple. As he desperately attempts to include his Uncle Toby’s anecdotes, his father’s bizarre philosophies and accounts of his own mishaps, he finds himself caught up in endless digressions. He writes:

I was just going, for example, to have given you the great out-lines of my uncle Toby’s most whimsical character; – when my aunt Dinah and the coachmen came across us, and led us a vagary some millions of miles into the very heart of the planetary system [….] …but some familiar strokes and faint designations of it, were here and there touch’d in, as we went along, so that you are much better acquainted with my uncle Toby now than you was before.

When Tristram is rendered incapable of expressing truth through conventional sentences he resorts to a system of hyphens, dashes, and asterisk. In some cases he uses visual aids to by-pass language: a flourish of Corporal Trim’s cane is represented by a squiggle; a marbled page represents the impenetrable mystery of the universe; a blank page allows the reader to draw their own portrait of Widow Wadman.

Gradually, Tristram understands that his burgeoning collection of disparate shaggy dog stories, diagrams, gossip, histories and biography is a narrative that moves towards a goal, albeit a fragmented one in which the hero rarely gets a look in.

The machinery of my work is of species by itself; two contrary motions are introduced into it, and reconciled, which were thought to be at variance with each other. In a word, my work is digressive, and it is progressive too, – and at the same time.

Compare this to the 1991 work of "non-fiction", PrairyErth, described by its author William Least Heat-Moon as a "deep map" of Kansas. Where Sterne’s narrator attempts to express a life in its intricate detail, Heat-Moon attempts the same with a geographical place. He carves the county into a grid system, exploring each one in turn, covering its topography, geology, wildlife, climate, social history, politics, local legends and fables. The book vacillates wildly in tone, form and style. Some are highly subjective poetic tracts, others are meticulously factual, to the point of being dull. Interviews are transcribed and reproduced seemingly in whole unedited form. At the beginning of each section he lists huge numbers of themed quotes from authors, politicians, local residents and artists – from what he calls ‘the commonplace book’. There is found art, such as the ‘Illustration of Cotttonwood Falls’ (1898) by D.D Morse and pictures of paper scraps he finds on the floor. He lists a full inventory of possessions of a man who died in 1860. One chapter listing all the prairie birds is a cross between encyclopedia entry and poetry. It’s as if the author is collating scraps, data, pieces of the puzzle. He self consciously admits his struggle to get everything down:

The materials of this book had been moving about and arranging themselves like iron filings: I, a magnet, moved and they shifted but kept various patterns. After a few months I began to see what would fill these seventy-six chapters, although usually not how I would do it.

Heat-Moon talks despairingly about the ‘black hole’: those bits of the book he couldn’t fit in.

These people and things are absent not simply because a book can’t include everything… but rather because my explorations quite early began forming into a gestalt that seems to control what I am capable of writing about.

In an explicit reference to The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, he creates a blank page, writing, "Perhaps, I having failed, you are to be its author". Heat-Moon’s frustration is with the one-way process between writer and reader. In one chapter he hands over authorial responsibility, providing a "dream-kit" of fragments to be pieced together by the reader, "for you to put your imprint on."

His goal in all of this is not to experiment with form, but to communicate how we experience a place. For a place is more than a sequence of agreed historical events, a map or a topographical description. It’s also a walk. A passage of time. A moment of clarity. A deep fear. A clash of noise, colour and feeling. A rumour. A story overheard. The site of a crime. The aftermath of an event. The prelude to a disaster. A series of fragments you piece together. A story you tell. You warp the reality of a place as you walk through it. In turn, a place changes you, such as when Heat-Moon comes to a ledge of limestone and shale layers, leaking water. Hypnotised into a reverie by the "tick tick tick" of the dripping water he undergoes the sort of transformation that JA Baker would recognise:

…everything between forms of liquidity, and all things forms of liquidity: the harrier a feathered bag of nutrient waters falling onto the furred sack of sapid juices, thirsty for hot rodent blood it can turn into flight; and what was I but a guzzling sweating bag of certain saps waiting to give up its moisture: press me dry, powdery dry, and you’d have a lump of mineralised soil, about enough to pot a geranium.

Because of its sheer scope (and possibly its 622-page length), PrairyErth has been described as "the non-fictional equivalent of the great American novel." But how much is it an equivalent? If the latest novels which embrace non-fiction are perceived as the literary cutting edge, what about the many non-fictional works that embrace the concerns of novels? Can PrairyErth be seen as a novel? Does it even matter?

Let’s reverse the angle. You could view Melville’s Moby Dick as a ‘deep map’ of the whaler’s ocean. In his introduction to the 1992 Penguin edition Andrew Delbanco writes that the book "furnishes one dazzling solution after another to the persistent literary problem of conveying to an innocent reader the palpable reality of an unfamiliar world". To greater understand the context of Ahab’s quest for the whale, Melville pushes the reader through extracts, anecdotes, and essays on philosophy, anatomy, art, religion and the history of whaling. Are these non-fictions digressions from the core fiction? Or, as Sterne’s hero puts it, they progressive, pushing the narrative along in ways that traditional story arcs can’t do?

Iain Sinclair’s Hackney, That Red Rose Empire, is one of those books slotted into the category of "travel/fiction". As a long-term Hackney resident and obsessive walker, Sinclair’s voyage is highly digressive and as much a map of his mind than a place. The subjective poetic and objective historical or share the same chapter, page, even the same paragraph. This is a style pioneered in Joyce’s Ulysses, itself a form of deep map of Dublin in which Stephen Dedalus, a version of the author, is an encyclopaedic cipher for literature, history and art, whereas Bloom is that more visceral experience of a place – defecating, eating and lusting. Sinclair is as a central character in the Dedalus mould, a distinct voice holding the many fragments together. Like Heat-Moon and Sterne’s hero, he too struggles openly with how to present his material so it’s honest to the place:

I have been working on a Hackney book for a while now, heaping up insane quantities of material, logging interviews without number: forty years. And I haven’t achieved the starting point, that impossible first sentence.

Our experience of a place is never linear. It is historical, geographical, topographical, sonic, visual, emotional, anecdotal, and many other things besides. It exists across many points in time, in a liminal zone somewhere between the tangible world and our imagination.

W.G Sebald’s Rings of Saturn is a novel, but often described as ‘Fiction/Memoir/Travel’. Ostensibly a walking tour of East Anglia, the book digresses through history, famous biographies, art and geography – from bombing raids, the 19th Century silk trade and Joseph Conrad to miniature railway rides and decayed seaside resorts. It also includes art, such as the reproduction of Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson, which he verbally dissects. It’s not clear how true this book is. Rings of Saturn switches effortlessly from personal viewpoint to historical narrative and back, until you’re not sure which is which. As with Baker, there’s a sense of a deliberate refraction of perspective through the author’s editorial filter.

The same goes for Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia which incorporates history, anecdotes, personal impressions and biography. It’s categorised as a travel book but begins like a novel, when a piece of Mylodon (giant sloth) skin inspires his journey to South America. As well as a physical journey Chatwin undertakes a literary-historical one, taking in Butch Cassidy, Shakespeare, Darwinian evolution and ‘The Ancient Mariner’. These all pivot about the axis of Chatwin’s personality.

In Patagonia became controversial when characters who Chatwin interviewed on his journey later claimed he had fictionalised much of what he wrote. He countered that, "the word ‘story’ is intended to alert the reader to the fact that, however closely the narrative may fit the facts, the fictional process has been at work".

Would any of this have mattered if it had been called a novel? Perhaps people feel duped by those labels slapped on the back of books. Perhaps they want their ‘non-fiction’ to be utterly and indisputably true, despite the long and unsuccessful attempt of our greatest poets and writers to accurately recreate reality in the form of language. Back in the real world, writers who want to create something more than a history or guide book, must necessarily embrace techniques of non-fiction. Author Robert Macfarlane says of Chatwin:

What I learnt above all from Chatwin is that travel writing – unpropelled by any narrative except the journey itself – must find alternative momentums. He taught me that pattern can substitute powerfully for plot: that apparently unconnected details and images, sprinkled as iron filings through a book, might be magnetised into subtle arrangement.

Under this influence, Macfarlane’s own book The Old Ways switches fluidly between personal subjective impressions and factual digressions entwined together through highly poetic, emotive language. The flight of puffins sounds like "bank-notes being whirred through a telling machine". Two pools of water are like "the mountain’s own eyes, gazing skywards". For Macfarlane, a landscape is not a visual artefact, but a process of walking feet and whirring mind, where the traveller creates stories and leaves them behind like prints. The book is full of narrative ghosts, from preserved 5,000 year old footprints, to a treacherous silt path where people regularly vanish into the sea, to supernatural spirits which assail him one night when he sleeps in the Chanctonbury Ring, a cluster of beech trees on a South Downs hilltop.

For me the most powerful example of this fusion of forms is Laura Oldfield Ford’s Savage Messiah. Categorised as ‘art’ this collection of her cut & paste zines incorporates images and words in equal measure, dancing together to create a powerful single narrative. Savage Messiah portrays a marginalised culture, class and political outlook. A world of decayed brutalist structures, drug taking, parties, frantic sex and violent protests. If Moby Dick is an approach to the "problem of conveying to an innocent reader the palpable reality of an unfamiliar world", then this book is about portraying the torn world Oldfield Ford inhabits. It’s not borne of some fetish for decay, or sentimentality for a revolutionary past. This is a living landscape with its own attractions – for those who are initiated. "There was a toxic pall over the city," she observes, "but as it shimmered and gleamed in the pink light I was struck by its beauty." As with Heat-Moon and JA Baker, Ford undergoes marvellous transformations in this landscape:

The whole Island shrunk and I soared above and I wasn’t on the Island anymore but in a faraway place alone and the more I reached out my hands to then island the further back it recoiled until it was just a blot. The lifts were broken and I was forced to the other zone, that staircase where the windows were narrow and lovely like a fortress and they rained down the block like arrows.

As an object in your hand, Savage Messiah looks like the world it attempts to describe: fragments of text strewn amongst scuffed, black-and-white images of pylons, tower blocks, underpasses and shuttered shop fronts. There are tales of betrayal, sex and camaraderie. Portraits of friends, comic strips, zine front covers and drunken group photographs. Sections lifted from newspapers, short stories, web addresses, graffiti, quotes from writers like Ballard, and fragments of text cut and pasted across images. "I’m picking through the relics of an abandoned London" writes Oldfield Ford. Her sole aim is not to dazzle with multimedia experimentation but to convey a woefully unreported reality through the idioms of that world – self-published pamphlets, typewritten essays and confessionals, fly posters, comic books, song lyrics, punk poetry. From page to page the writing switches from present to past tense, first person to third person points of view. They intertwine, deepening your understanding of her world as you travel back and forth through her fragmented memory of "old London, a place that existed at the back of my mind when I was much younger still, of secret pathways, kisses and perfumes".

Yes, pedants could say this is, technically, a collection of zines threaded into a book and could never be considered as a novel, but then Dickens’ novels were consecutively published in newspapers and, for me, Savage Messiah reads as no less a novel than Burroughs The Naked Lunch.

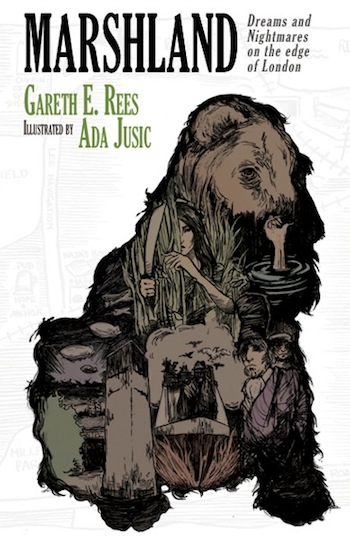

While I don’t mean to place myself in the pantheon of writers I’ve just described, I have my own insight into the process of creating a hybrid work. My book Marshland: Dreams & Nightmares at the Edge of London (illustrated by Ada Jusic) is a result of five years of walking my dog on the Lea Marshes in East London, a strip of greenbelt on the edge of Hackney. In this semi-rural wetland, ancient marshes are ringed by waterlogged ditches where herons hunt. Forests grow in abandoned Victorian filter beds. Cows graze in medieval meadows, scarred with World War II bomb craters, framed against a skyscraper skyline. Scrubland bears traces of sexual encounters and illegal raves. Homeless people, acid heads, alcoholics and adventurers move among the black poplars.

I spent the previous two years attempting to map the place on my blog, The Marshman Chronicles. Some posts were functionally descriptive, others recounted personal adventures, such as my unwitting trespass into a secret cottaging area. Others were weird histories: the bridge where the first British aeroplane was built, a 19th Century sex cult leader, a xenophobic Prime Minister of a tower-block micro-nation, Viking marauders and sightings of crocodiles and bears. I found that these descriptive or historical pieces didn’t entirely capture the idiosyncratic strangeness of the marshes, or convey the imaginative journeys I undertook when my mind wandered. Soon fictional stories began to emerge from the bog. A mysterious time-travelling narrowboat, raving zombies on the River Lea, a yuppie couple haunted by a dead toy factory, book-selling tribes in the 22nd Century.

When it came to putting a book together, I could have written it as a novel with fictionalised central characters and a story arc. I could have created an unofficial guide, a history or a psychogeographical travelogue. But I felt that to express the marshes in the way it mattered to me, I needed to have all of these elements in the same book, sharing the same space, informing each other. I went even further, including reference notes, music playlists and reviews of albums I listen to while walking and my own song lyrics. Finally I collaborated with Ada Jusic, a talented illustrator who adds a striking visual element to the book, even turning one of my chapters into a comic strip.

So is it a novel? Probably not. But neither is it a work of non-fiction, being composed of supernatural stories, comic art, lyrics and folklore. Perhaps it’s described best as a form of deep map, a book about the subjective experience of place in a long tradition spanning both fictional and non-fictional forms of writing. Or perhaps it’s time to ditch the labels altogether and embrace that uncategorisable writing which lingers outside the walled garden of literary fiction. After all, as Tristram Shandy puts it "Every author has a way of his own, in bringing his points to bear."

Gareth E. Rees is author of The Marshman Chronicles blog. His debut book Marshland: Dreams and Nightmares on the Edge of London (2013) is out now in all good bookshops and available to purchase via its publisher, Influx Press. His music and spoken word collaboration with Jetsam, A Dream Life of Hackney Marshes, is out on the Clay Pipe Music label