Despite the modernist upheaval of almost all artistic forms. Despite Finnegans Wake, In Search Of Lost Time, To The Lighthouse. Despite the Beats’ experimentation with syntax. Despite deconstructionists’ tearing up of texts, their attempted usurpation of the author. Despite David Foster Wallace. Despite the emergence of a hypermediated, hyperconnected, multi-screened, technology-defined world that has brought with it a proliferation of forms and mediums of artistic expression, multifaceted ways of presenting information, conveying meaning. Despite all of this, the novel today largely remains, somewhat depressingly, entrenched in the narrative cage of 19th century storytelling, with its linear, chronological, coherent structure and focus on characters, their rising and falling.

David Shields told us as much in his 2010 post-modernist collage Reality Hunger, a manifesto pleading for more lyric essayists than fiction writers, or at least a greater merging of fictional and nonfictional art.1 ‘The novel of characters… belongs entirely to the past… Two hundred years later, the whole system is no more than a memory; it’s to that memory, to the dead system, that some seek with all their might to keep the novel fettered,’ Shields quotes, contentedly pilfering from Alain Robbe-Grillet’s collection of articles For a New Novel from 1963.

There is little doubt plenty of pablum perpetuating this “system” dominates bookstores’ shelves. Horribly saccharine Richard and Judy-approved drivel, needlessly protracted fantasy yarns that get turned into considerably more visceral TV shows, works of historical fiction that win a load of literary awards, and whatever the fuck it is Paulo Coelho writes are far popular than anything that borders on what we could justifiably call progressive. And popular fiction has moved on little over the last decade or more. Back at the turn of the millenium, J.K Rowling and John Grisham topped bestseller lists. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

At the same time, the novel has become less important as an artform. Even publishers are accepting it. One of the most exciting things Random House is doing right now is Black Crown, an interactive game authored by youngster Rob Sherman, which draws a narrative as the reader/gamer/character makes decisions. It’s Choose Your Own Adventure 2.0. There are splinter narratives too, in the form of purchasable e-books, inviting further investigation into the created world, asking us whether we actually want to read or just play. Fiction’s native home is not inside two covers any more.

But, whilst the novel isn’t as vital as it was before medium saturation made the authorial life a considerably less attractive proposition (sorry, probably to most of you reading this, who are workin’ on your novel…), there are so many fresh writers2 proving the form is still invaluable. Not only are they wrestling the novel’s grim reaper to the ground, punching a few more sutures into his already cracked skull, they’re stretching our ideas of what fiction is, what “fiction” even means, challenging Shields and yet fully embracing his clarion call to create works with a hefty dose of “reality”.3 In doing so, they’re extending literary fiction’s lifespan for the sake of all our souls.

Take Adam Thirlwell, a guy dedicated to finding the “ideal” narrative voice. In his foreword for Juan Pablo Villalobos’ novella Down The Rabbit Hole, he notes the author’s ‘deadpan, innocent, damaged, matte, devastated’ linguistic patina, concluding: ‘This is what might represent one future for an adequate fiction – a fiction adequate to what’s happening.’

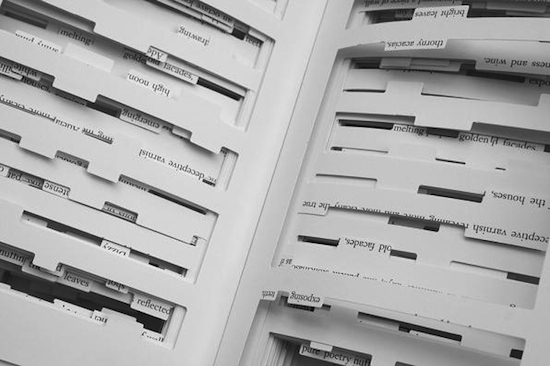

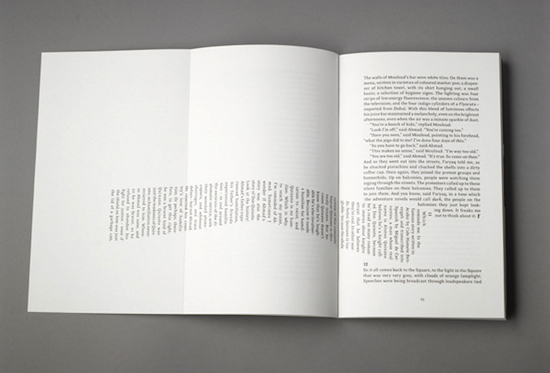

In Kapow! we see Thirlwell totally wrapped up in this idea, digging for the right style amidst the background of the Arab Spring. He erases the binary relationship between author and audience, layering multiple stories – anecdotes, fables, parables and more – from myriad sources, arranged in various forms: text presented the standard way, then in geometric shapes, some running across pages, invading white spaces usually ignored by the traditional novel, others upside down in the middle of the page. Some are single sentences, dissecting paragraphs. The text revels in the grand intertextuality of life, the infinite nature of stories, ones that relate to each other, unfold and collapse within one another: ‘Because if a story’s extended in one direction then it might mean that the story was being extended the other way – and that the story you thought was real, in which all the other stories were contained, was in fact – like, wham! – part of another story, of which you knew nothing.’ Indeed, much of Kapow!’s punch is delivered via negativa; deconstructionist ideas abound.

Thirlwell is, on the face of it, audaciously challenging the basic technique of Western reading down the page and from left to right, intimating we might not even be reading adequately. The whole thing centres around revolution in Egypt, where, of course, reading is done in another direction. ‘I was still beginning to wonder if I could in some way construct my own Arabic novel,’ the narrator says early on. ‘I wanted a new era of world description.’ In blowing up traditional ideas of storytelling, he is also yanking the reader into an epistemological debate about how knowledge should be displayed, where it comes from and which bits matter. Some stories are apparently replete with meaning – the theodicy of Sadiq, the man whose good deeds are a ‘source of evil’ – others seemingly inconsequential – ones ‘that the usual story would edit out, but reader I cannot’. The narrator questions how he should write about “historical events”. Why was Osama bin Laden’s death ‘too late for it to be meaningful’?

Just as some pages reach out to the reader, Thirlwell has his text rummage around in the liminal space between the page and the reader’s cognizance. The final narrator, the one who relays the variegated stories, becomes almost insignificant, just a ‘multiple sarcasm’, in a Barthesian move.4 Eventually, the narrator becomes wholly unsure of his purpose, wondering if he ‘should be trying to make movies, not stories. They seemed more true, or acrobatic.’ Yet the narrator’s ultimate defence of his art, in the longest, most chaotic pull-out, is a righteous declaration of the beauty of describing ‘in every direction and who gives a fuck about what it looks like’.

If some authors step into the mirror, reflect a narrative to the reader, Thirlwell walks through the mirror, grabs the reader, drags them inside, and pummels them with ideas until some kind of compromise is made on the value of literature. Others stand inside the mirror, staring the reader dead in the eye, reflecting the absurd mundanity of “life” to their audience, Tao Lin being the obvious example.

In his deadpan, terse, anti-fluff way, Lin manages to do a lot more than he is credited for – namely posing like a hipster.5 Lin is capable of saying plenty without ostensibly doing much at all. That’s something Kafka mastered: Lin is doing the same, albeit sans phantasmagoria and with hefty doses of humour.

Richard Yates, a book in which everything is “fucked”, is Lin at his most stripped-down. He recognises that in simply relaying the bare, quotidian existence of his “characters” in such a sparse style, he exposes how bizarre people are. Lin’s nomenclature tells you enough; the central characters are Haley Joel Osment and Dakota Fanning. Say them in full and they sound pretty odd. Say them repeatedly as the text does and they become even odder.

But its in Haley Joel Osment and Dakota Fanning’s throwaway remarks about suicide, rape, onanism and other “risque” subjects that the surreal emerges from the bland. It’s Beckett without the effort. It’s why you get passages like this:

Haley Joel Osment said he wanted to funnel boiling water into his brain.

“That would be good,” said Dakota Fanning. “I just thought of Bono and felt suicidal.”

His latest, Taipei, is more expansive. There’s actual metaphor and simile.6 That means stylistically, it isn’t as consistent as Yates, but there are many more ideas floating around as a result of the added dose of textual messiness. Lin builds on his big “communications” theme, making anti-protagonist Paul computerised – his memories stored as if in external hard drives, accessible at times, but never at the forefront of his consciousness.

To counter that, there is a pervasive uneasiness of having lost what late historian Tony Judt would have called “the power of forgetting”; the Internet, storing all our knowledge and memory for us, destroys that faculty, whilst making us unforgettable public beings. Privacy is dead. And ultimately, Lin, in one of his more searching, elegiac, Ballardian pieces of prose, suggests the computerised generation, in outsourcing the most core human functions to machines and simultaneously internalising technology, is all but dead too:

At a certain age, he remembered, he had often lain motionless on carpet, or a sofa, feeling what he probably viewed, at the time, as boredom and what now seemed like ignorance of – or passive disbelief in – his forthcoming death, which would occur regardless of his thoughts, feelings, or actions in the unknown amount of remaining interim, upon a binary absorption from some incomprehensible direction, taking him elsewhere.

Lin exhumes the “unreality” from “reality”. But whilst the autobiographical leaks into his work, especially in Taipei, which has plenty of memoir-ish qualities, he isn’t talking explicitly about himself. Others are doing that inside the novel, and it is female writers doing it best, their material fresher, less contrived than previous confessional literature. In the pseudo-philosophical novel How Should A Person Be?, Sheila Heti splices transcriptions of conversations and emails from her real-life with her fictional interactions. It’s no surprise Shields is a fan. There are no barriers between fiction and nonfiction, there is no blurring, only erasure.

But it is one of Lin’s Muumuu House buddies, who also likes to slice off large chunks of “reality” and paste them onto the page; someone who is really taking this method to the extreme, and has already pissed off much of the “erudite” literary traditionalists. Marie Calloway, the latest enfant terrible to hit the scene, with her possibly-autobiographical tales of sexual encounters, is inevitably going to become the Tracey Emin of the novel, bearing her sexual soul as she does. And people should embrace it. We need something to rattle the cage, someone for whom nakedness, literal and metaphoric, and sex, with all its uncomfortable detail, are the central pillars of the storytelling (Aren’t we all used to explicit material now anyway? In Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater a character masturbates over a grave and then licks his jism from the flowers. It won a National Book award. Surely we accept the disgusting is often essential to great fiction, no?).

Calloway’s writing in what purpose did i serve in your life is inelegant, often benumbing and uncomfortably adolescent: ‘But then he kneeled down and started to go down on me, which was really gross. I don’t like it even when a really hot guy does it.’ But it is all part of her self-conscious, insecure schtick. The writing is flawed because she is flawed, in her unflaggingly vulnerable way. It works because it is adequate; tone matches content.

Not content with scruffily copy-and-pasting communications from her life into her work, Calloway makes her physical self a spectacle too, close-ups of her body parts peppering the text, objectifying herself yet remaining the core subject of the book, inviting us to explore the lines, the curvatures of her physical self. We are asked to respond to her youth, her sexuality, the whole Calloway exhibition; it’s not for nothing she plonks criticism straight into the piece. Calloway covers fresh ground not by describing overt sexuality, as titillating as that is, but by jostling with the meta-textual, the fictional vs. non-fictional Marie Calloway7, the author vs. the artistic subject.

But there are writers who refute the need for obvious reality, who show us an almost-straight narrative can carry weight, whilst entertain. Ned Beauman is the leader of this pack. The Teleportation Accident’s almost inscrutable cat’s cradle of an opening feels like a manifesto in itself – accidents, or events, allude, “but they don’t ape”, the narrator says in that charmingly glib tone, and it doesn’t matter what time you’re in or what grounding the novel has in “reality”, everything is linked, either through the laws of physics and our shared place in space-time, or across literature itself. The latter is the more important to Beauman, with The Teleportation Accident’s constant referencing of artists: our peripatetic hero Loeser’s loathing of Brecht, another character’s lies about knowing Hemingway, nods to Balzac, Roth, Mann, T.S. Eliot, Dadaism, Sartre. Then there’s the Pynchon-esque mythologising of imagined texts: The Lizard King, the story of set designer Lavicini, and the mystery of his creation, the Teleportation Device itself. Literary allusion is internal to the text and external, and has real-world value.

There is plenty of “reality” in Beauman’s Booker-longlisted novel. That’s kind of the point of the allusionary stuff. Much of the novel is a comedy of manners, dealing not with post-World War I Depression-era bohemia and Nazism, as the surface would have us believe, but quite clearly satirising the East London hipster scene. Why else would Loeser and his companions chat ad nauseam about getting in some good coke? Why else would all the characters talk like they were at some shitty house party or hung over from one. There is no need for Beauman to write a novel about his experience of Shoreditch and its hinterlands; by distancing himself in an apparent roman à clef, he remains connected to his ultimate meaning, yet gains perspective, meaning the Teleportation Accident doesn’t come off cloying or clanging or cringing like Lin’s and Calloway’s prose can do, even though they deal with a lot of the same “stuff”.

Like Thirlwell, he is also unsure of the necessity of Westernised literary fiction. ‘English fiction is dead,’ declares one of Loeser’s rivals, Rackenham, who pilfers ideas from our failure of a protagonist (art is theft after all). The characters, including the elusive heroine Adele Hitler, are even inadequate in the context of their time, idling to one Gatsby-esque party after another, unaware of the historical significance of their present, or even their nomenclature. Through the hopeless agnosia sufferer, Colonel Gorge, Beauman suggests a world where everything can be made into fiction is one the mind would not be happy to inhabit. Fiction is not everything after all.

Although one artist who might disagree with the inadequacy of fiction, and yet continues to transgress norms, to astound, is Ali Smith. There But For The… opens with a man on a cycling machine, his mouth and eyes covered in censorship strips, and a child trying to pry them from his eyes. That’s before a guest at a dinner party locks himself in a bedroom. It’s experimental, it’s wrapped up in ideas about modern communications like Lin’s work is, but is stranger and, frankly, more beautiful.

Then there is Artful – a blend of lyric essay and fiction, a story of loss told via lecture notes and the narrator’s reaction to them. They were originally delivered as a series of lectures, truly erasing the line between the “real” and the “imagined”.8 And at its most poignant moments, it is a treatise, an encomium of the imagination and the novel, one that surpasses Shields’ Reality Hunger in its eloquence, in its expression through form. In the final note within the fictional lectures, Smith sums it all up, but in a typically classy truncation, leaves us hanging:

Here’s to the place where reality and the imagination meet, whose exchange, whose dialogue, allows us not just to imagine an unreal different world, but also a real different world – to match reality with possibili

Back to Kapow!. It left me wondering, perhaps we really do need a novelistic revolution. If self-ordained hyper-literary types like you and I find ourselves tired by conventional narratives, and they continue to swamp the artistic landscape, maybe the whole scene does need a shot in the arm.

Despite the cadre of writers listed above pushing out what could be described as “innovative” fiction9, it doesn’t feel like we’re in the midst of a period-defining movement, even despite the economic ties between our time and that of the modernists. Maybe we’re too cynical, maybe the Internet has grown the critical landscape to such an uncontrollable behemoth we won’t ever get our revolution.

Or maybe that’s just impatience. In our miniature lifespan, it has been an infinitesimal gap between us and the modernists. And, as Kapow!’s narrator says, revolution takes a rather long time. Or as his taxi driver would have it: ‘You think it is just the carnival in the Square? You think it is just fiesta?’

- Shields is unashamedly a lyric essayist, so the book, despite its genius, is partly a 200-page piece of self-marketing

- Not you Barnes, Amis, McEwan, Roth, Pynchon – literature’s unmoveable, curmudgeonly, beloved living deities

- As Nabokov said, “reality” is meaningless unless inside quotation marks

- You can still feel Thirlwell’s zippy language though, his immutable wit… fortunately, as it propels the thing along

- Yes, he is irritating, but so was DFW – remember all those tiresome footnotes, parentheses and acronyms, especially in Infinite Jest? Yet we were still thrilled by it

- Although, as with Richard Yates, if you picked it up, flicked to a page and read something out of context, it would read like the worst book ever written. Context is necessary in “getting” Lin, which is ironic because his characters are so heavily decontextualised

- Not her real name, we must remember

- Obligatory meta box officially ticked

- I know, there will be many more, just tell me what a moron I am in the comments