Here at tQ towers we’ll be loading up on Pabst Blue Ribbon and heading down to the Southbank in February to luxuriate in the BFI’s retrospective season David Lynch: A Reputation Precedes…, which spans the entire month and boasts multiple screenings for all of the pioneering US filmmaker’s features to date.

Presented alongside rare big screen outings for early shorts The Alphabet (1968), The Grandmother (1970) and The Amputee (1973), his monochrome full-length debut Eraserhead remains a startling study of industrial dread, surreal dysmorphia and new parent angst. The epitome of a low-budget cult hit, it led to the Missoula-born auteur being hired by producer Mel Brooks (uncredited, to avoid the assumption they were doing a comedy) to helm 1980’s poised, black-and-white treatment of The Elephant Man, which further displayed Lynch’s gift for locating a transformative beauty amid the grotesque (and picked up eight Academy Award nods to boot, losing in every category).

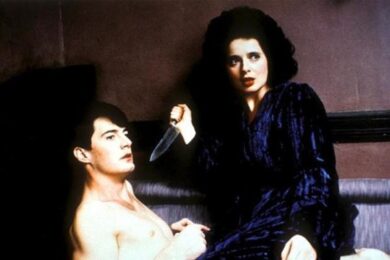

His next studio project – a $40 million attempted blockbuster adaptation of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi novel Dune – is still controversial for acolytes and has been disowned by the man himself. Be sure to read the Quietus on Monday for Andrew Stimpson’s spirited defence of this ambitious folly, which was conceived by legendary executive Dino De Laurentiis. The latter’s patronage also facilitated 1986’s peerless Blue Velvet. Its myriad themes – a small town’s grim underbelly, the fine line between sleuth and voyeur, feral sexuality as metaphor for domestic abuse – codified Lynch’s dark humoured signature: erotically charged, fever dream design; psychological torment blended with violent physicality; a restlessly imaginative burrowing into the rotten core beneath an apple pie facade. This imperial phase would of course continue on TV. Groundbreaking global smash Twin Peaks elevated ‘Lynchian’ into the modern vernacular, a pop culture byword for disturbing symbolism, moral ambiguity and abstruse, oft-parodied eccentricity.

Stylistic tropes and iconic characters seared into the collective consciousness, the 30-episode mystery’s lexicon-changing impact inevitably eclipsed its creator’s subsequent cinema output. Wild At Heart scooped the 1990 Palme d’Or but got a mixed wider response. An overheated cocktail of high octane melodrama, star-crossed romance and breathless invocations of touchstone Americana (cf Elvis Presley, The Wizard Of Oz), it’s easily dismissed by too mature viewers as a disjointed pile-up of brash, wilfully bizarre images that signify nothing much. Snakeskin jacketed hero Sailor Ripley furiously chews the scenery while cartoon villain Bobby Peru swallows something deadlier, the whole white trash shooting match drenched in bloody camp. However, for those fans gripped by a distinctly unironic adolescence at the time, this broad strokes road movie offered a vivid glimpse (usually via late night television) into the exotic transgressions of an adult world.

Two box office flops followed. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is the pulpy, blunt force trauma prequel you should only really see after digesting both seasons of the more sophisticated, cathode ray tube phenomenon. Its lurid reconstruction of homecoming queen Laura Palmer’s last seven days was reviled by a snooty establishment, premiering at the Cannes Film Festival to boos. Nonetheless, …Fire Walk With Me provides an essential piece of the puzzle for Twin Peaks diehards plus a graphic contrast to the parent series’ nuanced majesty, arguably befitting the horrific, innocence corrupted subject matter. Undeterred by failure, Lynch plunged deeper into the noir with 1997’s underrated Lost Highway, which revels in a Moebius strip adultery/murder narrative, hallucinatory sequences and the odd bit of taut action (one death scene in particular just sticks in the head). Seasoned observers who’d grown comfortable with the director’s double-meaning recontextualization of vintage rock & roll tunes were perhaps alienated by Trent Reznor’s excellent gothic soundtrack (studded with suitably gloomy numbers by Rammstein, Marilyn Manson and contemporaneous David Bowie), but the music helped this alluringly seamy thriller resonate with a younger generation who weren’t even born when Eraserhead came out.

Based on the real-life tale of a Midwestern pensioner, The Straight Story (1999) served as a sunny side up rejoinder to Lynch’s detractors, elegantly crafted proof that he could handle linear structure (albeit involving an epic journey on a lawnmower). The turn of the millennium saw him return to trademark left-brain plotting with late period masterpiece Mulholland Dr.: a melancholic, hall-of-mirrors treatise on memory, desire, paranoia, guilt and reality in doppelgangland Los Angeles. This densely allusive picture rewards careful repeat viewings and has inspired reams of philosophical theorizing, but retains a shadowy entertainment value that goes beyond enigma-solving comprehension. Its critical and commercial success affirmed Lynch as one of the few creative geniuses extant within the Hollywood system, scoring his third Best Director nomination at the Oscars (the other two being for Blue Velvet and The Elephant Man; he’s never actually won). Half a decade later came supernatural/self-referential nightmare Inland Empire, starring Wild At Heart leading lady Laura Dern as an actress on the comeback trail trapped in a labyrinthine subconscious of gypsy curses, Polish prostitutes and humanoid rabbits. Its three hours were shot cheaply on digital video, yet are as richly unfathomable as a maze made of chocolate.

Lynch hasn’t released a follow-up, instead keeping busy with his paintings, transcendental meditation and last year’s acclaimed Crazy Clown Time album. While we wait, his ten movies so far comprise an endlessly watchable body of work, each indelible vision worthy of fresh celebration or ripe for reappraisal. Yes, even the one with Sting in.