The Hollywood blockbuster axis tends to hold true to the notion that an audience’s every emotional response ought to be guided to the nth degree. Sound and music is specifically co-ordinated to ensure that every single person watching a film feels exactly the same way at exactly the same time. There’s a tyranny to that method (‘the Disney approach’, perhaps) that mirrors the big build/key change dynamic of most modern pop music, something pushed to grotesque proportions in the phenomenon Daniel Barrow recently identified as ‘the Soar’. Both cases insist on dictating to an audience how they’re supposed to react. Both remove the potential for anything approaching either personal interpretation on the part of the viewer/listener, or creative ambiguity on the part of the director.

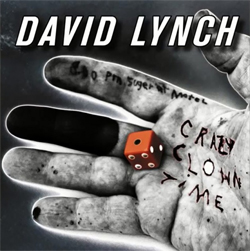

Those parallels bear thinking about in the case of David Lynch’s debut album, because for the majority of his directing career he has set himself up in direct opposition to the homogenising of art into IKEA entertainment solutions. He prizes ambiguity, refusing to give away anything but cryptic clues as to the intent behind his films. In the hands of a director who thrives on surreal and vaguely threatening moods and situations, the lack of background can be frustrating. But it’s also essential to the underlying appeal of his approach. Inland Empire and Lost Highway might not be particularly easy to understand, at least not on a conventional level, but they leave a great deal of space for individual interpretation. The same is true of Crazy Clown Time – it’s unsurprising that Lynch doesn’t exactly take an obvious lyrical approach, even if his songwriting is rooted in bar-room blues, jazz and electro-pop. It certainly gives very little quarter to anyone wondering exactly why he’s chosen to take a detour from filmmaking into pop music (not exactly known for being the most auspicious career move). Thankfully though, it’s more than the vanity project some might have expected. It is a peculiar little record, but it hangs together very well, and makes a reasonable case for his ability to wring something worthy out of whatever art form he chooses to tackle.

It makes sense that, sonically at least, Crazy Clown Time offers rich pickings. More than most directors, Lynch’s films are memorable thanks to their clever use of sound. His 1977 debut Eraserhead, already an unsettling watch, was elevated to masterpiece of unresolved tension by the presence of a constant, scooped-out industrial roar in the background. During Twin Peaks familiar musical themes were used as anchors to the core series plot, even as storylines billowed outward in all manner of odd directions. The same was true of Blue Velvet, albeit on a smaller scale. And his ongoing soundtrack work with composer Angelo Badalamenti has established a very distinctive house style, all delay-drenched guitars and hanging diminished chords to signify tension – largely responsible for the decadent, vaguely ominous atmospheres that permeate Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive.

That same style informs the majority of Crazy Clown Time. Lynch’s guitar work throughout has the same jazz-gone-awry feel as the excellent Lost Highway soundtrack, and the same tendency toward sudden shifts in mood (that film featured tracks from the likes of Rammstein and Marylin Manson alongside the low-slung sleaze of Badalamenti’s dubby instrumentals). In fact, in terms of sequencing, composition and atmosphere, the album’s construction very much mirrors that of a typical Lynch film. There are long periods where comparatively little happens other than the slow, steady escalation of tension – the sepulchral drag of ‘Noah’s Ark’; the dramatic church organ drone draped across the backdrop of ‘I Know’ like one of Lynch’s iconic red stage curtains. There are sudden, brief flares of violence: the Karen O-featuring ‘Pinky’s Dream’ opens the album in a stifling rush of burning rubber and exhaust fumes, and the title track is voyeuristic and subtly sexually aggressive, reminiscent of the treatment of Lynch’s female protagonists in several of his films. A couple of moments of disarming emotional openness provide the album’s highlights. The lush pop of last year’s single ‘Good Day Today’ finds Lynch shifting to a fragile, reedy falsetto that suits his nasal drawl. Along with the beautiful, lovelorn ‘Stone’s Gone Up’, it’s the only song where he drops the cryptic/nonsense wordplay in favour of something slightly more accessible.

There are also, of course, those requisite moments of out-and-out strangeness. The narrator of ‘These Are My Friends’ repeatedly spells out a list of his acquaintances – who may or may not be imaginary – in the manner of someone rocking back and forth in a locked hospital cell. Album centerpiece ‘Strange & Unproductive Thinking’, meanwhile, is a struggle to get through. Less directly connected to his cinematic themes, here a long, vocodered monologue about the benefits of self-examination (clearly a nod to Lynch’s professed love of transcendental meditation) stretches out over nearly eight long minutes. It doesn’t really go anywhere, save a cripplingly funny last ninety seconds that suggest improved dental hygiene as a cure for the ills of modern life ("the possibility of the breaking of relationships based on the idea of negative distortion of the mouth, for teeth, though not necessarily considered one of the primary building blocks of happiness, can in fact become a small sore festering and transferring negative energies to the once quiet and peaceful mind").

It’s fair to say, though, that the success of Crazy Clown Time does depend largely on your opinion of Lynch himself. His singing voice could certainly pose problems for the casual listener. Though the songs themselves are melodic enough, he has little interest in delivering his vocals to match – many are whispered, or delivered in high-pitched sing-speak with little regard for remaining in tune. Anyone put off by Lynch’s unashamedly self-indulgent, unforgiving approach to filmmaking is unlikely to find too much to love here. However, from the perspective of a fan its very Lynch-ness is the album’s defining characteristic: it’s frequently like spending an hour in the company of Twin Peaks‘ Gordon "I’m worried about Coop!" Cole, and offers a rare chance of a glimpse into the enigmatic mind of the man himself. Given that there’s no sign of a new film on the way, it might be the only opportunity we’re afforded for quite some time.