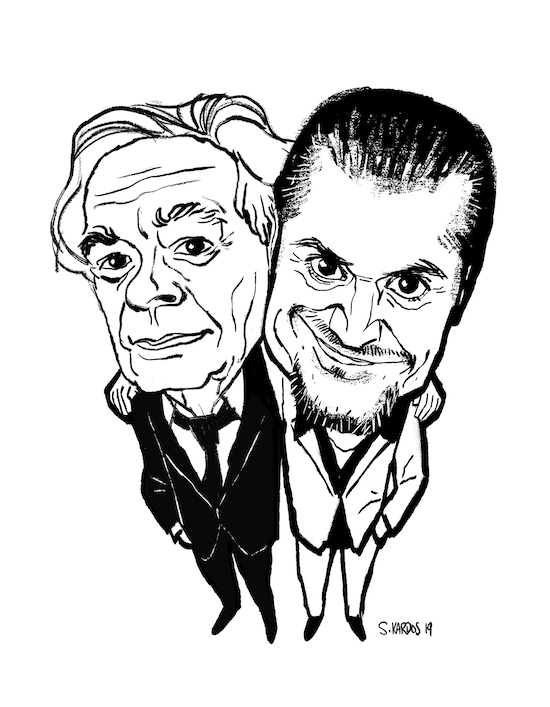

Illustration by Stéphane Kardos

In Terry Gillam’s 1981 movie Time Bandits, six dwarves are sacked by the Supreme Being for inventing the Pink Bunkadoo, a six hundred foot bright red tree that smells terrible. Chances are, Randall, Fidgit, Strutter et al had a hand in creating the corpse flower, an inflorescent monster of a plant native to Indonesia that can grow up to three metres tall and smells of stinking death. Dung beetles and flesh flies pollinate the plant and help to spread the odour of carrion far and wide. The schmaltzy ‘say it with flowers’ slogan presumably occludes the pungent amorphophallus titanum, which would leave you gagging should a delivery arrive on your doorstep.

A corpse flower is an oxymoron that is fairly typical in the solo work of Jean-Claude Vannier – the musical genius who for the last five decades has been the go-to man for the finest orchestral French pop known to man, helping to make Serge Gainsbourg, Johnny Halliday, Barbara, Brigitte Fontaine, Francoise Hardy and many more sound even more talented than they are/were in the first place (a recent book about him is subtitled: ‘L’arrangeur des arrangers’).

On his 2011 album Roses Rouges Sang Vannier sings about another botanical conundrum on ‘Au désespoir des singes’. The Araucaria araucana or Monkey-Puzzle Tree, grows up to 50m tall and baffles simians: “I love this tree because it has a funny shape, and thorns so the monkey can’t climb the tree,” he told me when I interviewed him for The Stool Pigeon around the time of its release, “so this is the monkey’s despair, but it is a metaphor… like life.” The title of that album, too, alludes to the fragrant and aesthetic beauty of roses juxtaposed against the thorns up their stem and, in the words of André Benjamin, the fact they “smell like poo-poo-oo” the closer you get to the ground. The natural world is full of lessons and Vannier is clearly fascinated by the beauty and the cruelty, which he often equates to affairs of the heart.

There’s lots of Vannier in Corpse Flower, though it’s been augmented, sometimes Americanised and, with no disrespect to Jean-Claude, improved greatly by one of the most extraordinary vocalists working today. Mike Patton doesn’t call upon his full range here; he’s up close to the microphone, brooding, playful and sometimes sinister. Some of Jean-Claude’s more earnest ideas written in French have been reshaped to comedic effect, like the final song on the album where Patton declares that he’s shat his pants from hard drinking (who hasn’t been there?)

“Actually that lyric right there, and most of those on ‘Pink And Bleue’, are a good example of me translating his intent.” Patton is speaking on the phone from his home in San Francisco. “In the original French lyric, it was something like ‘when I drink too much I lose control’. I was like, ‘fuck that’, so I embellished. There were a lot of examples like that.” Despite these alterations, there’s still a beauty tainted by bitterness, a paradise lost. “Yes, some French lyrics were adapted by Mike,” Vannier says by email, “but in French or in English the idea was the same. He wrote the lyrics to some of the others.”

The original hope for this interview was to get the pair of them in the same room, but like so many modern friendships, it grew online – and Corpse Flower was made electronically. Messages were exchanged and then files were sent back and forth across the Atlantic. Vannier came up with many of the initial ideas, Patton played the songs with his band in San Francisco, Vannier provided the strings and the orchestral parts from Paris…

Some songs, like the magnificently operatic ‘Hungry Ghosts’, were fragments that the pair then built a song around. “That’s something he had previously recorded,” says Patton. “I don’t know how he did it, or when he did it, or where it came from, but he originally sent me that idea, just as it was, and I was like, ‘Oh my god, we’ve got to write a song around this.’ He’s not a sampling kind of guy so he must have recorded it sometime.”

“The singer is Anne Germain,” writes Jean-Claude when I follow up by email. ”She was a nice chorist for movies and commercials, and a very good jazz vocalist.” Other songs on the album don’t give everything up on a first listen, like ‘Cold Sun Warm Beer’. (“You should never fall in love with a record immediately,” warns Patton. “It’s a fucking romance. You’ve got to wine and dine it, it’s got to wine and dine you.”)

On others, there are motifs that could have only come from Vannier, tonal and yet atonal, swooping in like sidewinders that kill you with a single bite. One classic example of Vannier’s idiosyncratic style manifests itself in the piano break on Gainsbourg’s ‘L’hotel Particulier’, which, if you listen to it closely, almost sounds like a mistake – but landing clumsily as it does in so much space, it knocks you sideways every time. On ‘Camion’, the orchestral flourish in questions creeps up on you in the third verse, approximately 1.50 seconds in, a lush orchestral riff that drops out of nowhere and resolves on a long drawn out note that feels wrong, and yet so right.

“That’s one of his shining talents,” enthuses Patton. “He’s got the absolute technique and delicacy of a classical composer, and yet he’s well-versed in jazz and rock and he likes to fuck shit up. And he does it in a really effortless way. It doesn’t sound like cut and paste, it doesn’t sound like postmodern bullshit, it’s actually composed that way. It’s with intent, and that’s why he’s really, really special. Not a lot of people can do that.”

The pair first met for a Gainsbourg tribute at the Hollywood Bowl in 2011, when the L.A. Philharmonic and some of the original crew from the Marble Arch sessions for Histoire de Melody Nelson (there’s still some debate about who did what, and who was present) reunited for a set of the legendary album with a cast that included Patton, Beck and Zola Jesus. Vannier’s lost masterpiece L’enfant assasin des mouches was then reimagined after the interval. Jean-Claude was invited to conduct.

Mike Patton had discovered Vannier’s work after becoming besotted with the music of Serge Gainsbourg. He found himself saying things like, “Who’s writing this stuff, the arrangements are so amazing?” and started to uncover some of Vannier’s more recondite recordings. “And I was like, ‘This guy is unbelievable!’ And then I got asked to do this Gainsbourg tribute at the Hollywood Bowl with all these other singers… it was a total mess, a clusterfuck but, you know, I’m in. If Vannier’s doing it then I’m in! Because I knew it wouldn’t be bullshit.” He adds: “It was so much fun. There were at least 15 different singers and we had to choose who was going to do what, and there was the L.A. Philharmonic… it was a wonderful mess. But really the anchor of that whole thing, and this is what impressed me the most and made me want to work with Jean Claude… he was the guy that held it all down. Eighty different musicians and as soon as he raised his hand everyone listened. That’s power.”

Their mutual appreciation eventually turned into a resolve to work together after Patton “popped the question”. Anyone who has heard L’enfant assasin des mouches (meaning the child fly murderer) might note a correlation between that and the more avant-garde work in Patton’s catalogue such as Fantômas or Mr. Bungle. Patton’s love of the Cardiacs, and musical digression, is not inconsistent with Jean-Claude’s jaw-dropping debut solo record. His label Suzelle were unimpressed with what he turned in in 1972, and the first pressing was limited to 200 copies on the record company’s insistence (it has since been re-pressed a number of times after it was rescued and reissued by Andy Votel’s Finders Keepers in 2005).

Despite what looks on paper like an intersection of sonic wet dreams, there were some disagreements at first. Vannier is known for his love of space, which goes as far as a deep hatred of the high-hat, which fills out lots of the middle on records. A Patton production, on the other hand, rarely embraces the ‘less is more’ mantra: “That was kinda tricky, because I’m a dense guy and he’s a sparse guy. I wouldn’t say we sparred over it but it was definitely something we had to think about. A lot of tracks on that record I had to pull way back from and just kinda let the music speak. That’s a hard thing for me, so this was an education. Honestly, it really was.”

Vannier comes from the tradition of French pop where an arranger is drafted in to do much of the heavy lifting from a melodic perspective, and with the rest of the production too. In many cases, arrangers would write much of, or all of, the music without getting a credit for it (see: the soundtrack for La Horse). There is usually a producer in the studio too, like with the British or American setup, though they’re generally not lauded like the Phil Spectors and Joe Meeks and Quincy Joneses of the Anglophonic world. There may be some similarity with Bowie’s Berlin albums and the dynamic between Eno and Visconti, though, having introduced the drumkit to the Eventide Harmonizer and fucked with the fabric of time, Visconti was anything but a button pusher. As my friend Matt Robin from the We Want Sounds label tells me: “The French industry was much smaller and very much geared toward mainstream pop which we called variété. In the 70s it would always be the same musicians recording for everybody so they’d just record in the same pop style. The A&R wouldn’t think too much about producers. They’d just get the musicians in and decide what style they wanted with the artist: Bossa is trendy? Let’s do a bossa. Disco is hip? let’s do a disco one…”

“I don’t know how it works with other arrangers in other countries,” says Vannier, “but when a label or a singer asked me to do some arranging, I would do the whole job: conception, style, writing arrangements, orchestrations, choice of the musicians, conducting all of the recordings, the orchestra, the solo voice, the mixes and everything else, freely, without anyone at my side. Usually the artist and the label only discovered the finished song and the arrangement after I’d recorded it.” He adds, perhaps pointedly, “In my opinion, the true composer should write all of the music and not ask for help from an arranger, like someone who needs crutches.”

In many cases the author would ask for far more than help, with the arranger providing almost everything without reasonable recompense, a songwriting credit or any of the adulation. With that in mind, it’s heartening to see Vannier receiving an equal billing on a record in 2019 and getting the credit that he deserves. Corpse Flower isn’t a record made with that same artist / arranger dynamic though. It appears to have been a learning curve for the great Vannier too.

“Yeah I mean look, I thought that [using Vannier as the arranger] would be too easy,” says Patton. “so I took a little bit more of a hands-on approach. It took a while to work out the system we were going to use together, and maybe another couple of years to figure out what that thing was. So I sent him a bunch of things that I thought would be appropriate, and he sent me a bunch of things, and to be honest, the way that seemed the easiest and most natural was for me to adapt to his songs as opposed to him to mine. I would help out with adding additional instrumentation, and more than often arranging. Taking the song and chopping it up and making it go in different directions, and then of course doing vocals.”

At first I wondered if the record was a concept album about Oscar Wilde. Vannier is a big fan of the Irish playwright, with opener ‘Ballad C,3.3’ using the words of Wilde’s The Ballad Of Reading Gaol, and ‘Browning’ could have been about the poet Robert Browning of whom Wilde once quipped "Meredith was a prose Browning, and so was Browning". “It’s about a gun, man!” counters Patton, “Browning is a gun.”

If there is an overarching concept, it’s that Corpse Flower should be a record without borders: “I wanted it to feel like this global nomad going to all these different places and using different languages, I mean there’s all sorts of shit on there, man. I kind of threw out the idea that it should sound like global nomad chaos,” says Patton, “but I didn’t want it to sound like it’s from France or fucking here. I wanted it to sound like a world with no borders. Easier said than done and I’m not sure it came out like that, but that was what was in my head and he loved it. Like a world music record without a world.”

In that sense, is it a political record then? “Fuck no, all I’m talking about is music.”

Given the success of Corpse Flower, is there any possibility that Patton and Vannier will reunite? “Yes, maybe we’ll begin another adventure,” says the Frenchman. “I have a project I’d love to do with Mike. We’ll see…”

As for their first record together, time travel played its part with Vannier amassing material from across the decades in order to reanimate the corpse. Some of the ideas he presented dated as far back as the 1970s, with plenty of others written specifically with Patton in mind. My curiosity gets the better of me and I ask Jean-Claude if any were written during the three magic years he and Gainsbourg stealthily changed French pop forever together. “No, not at all, they are not that old!” comes the curt reply from Vannier. “Past or present… what does it matter?”