I accept that when certain histories adhere it’s difficult to chip them off again. There is too much residue from all those stroked chins and all those dislodged breakfasts but c’mon you dewy-eyed fucks, this ain’t like the 60s or 70s or 80s where to a certain extent you could pull the wool over my eyes. I wasn’t there in 58 or 66, was barely cognizant in 76, only really started having a pop memory round about 1982 and even then just about missed out on anything that could be called a ‘direction’.

Whenever a musical epoch has been retrospectively looked at, being part of that generation that found itself in the wrong place at the wrong time, I’ve been suckered into the visions of others who were ‘there’. In the first flush of my love for 60s music that sustained me through the appalling sonic Blue-Stratos-bath of the mid-80s, even a dick like me could tell he was being sold a mixture of magic and snake-oil. Stuck up in Cov I was well aware of how a swinging capital can convince itself it’s the only story, how it’s easy to see a time as golden if you’re on the right end of the class & income scale (and especially if you’re paid to come up with such mind-lint about what an ‘era meant’), how for most people out beyond NW1 those supposedly revolutionary moments in pop culture passed by unregistered in the shitty business of survival. But c’mon now, in the usual 20-years-on retro-pattern that pop keeps on sticking to, things have now swung into an era I at least vaguely recall – the 90s. And you can’t fool me with this bullshit any more because I was there.

No matter how much you might want to erase my stuck-out elbows, the irritating refusal of thousands of us to get with that program or get down to the shit you’re now saying everyone loved back then. That ‘classic’ I hated. That ‘essential part of any rock fans collection’ I utterly despised. They weren’t my fucking records. They weren’t what my 90s sounded like.

As time goes on the arbitrary (but not really arbitrary, more authoritarian) choice of anniversaries-worth-celebrating reveals a prevailing dual-impulse in rock curatorship, the attempt to cast a frowny, head-shaking light on the present by pointing out ‘what we’re missing now’, coupled with an attempt to simplify the past in a blinding retina-flash that obscures the shades and shadows; a sepia yearning for the certainties of the big zeitgeist-defining phenomenon. There’s a colossal condescension being wrought in all this "20 years since Nevermind/ Screamadelica" horseshit. There is a constant assertion that such moments in some way reflect the ‘feelings of a generation’, that we all ‘belonged’ back then in a way we’ll never belong again. Now we’ve been liberated from the tyranny of the summer blockbuster LP or any sense of coalesced ‘movement’ in pop’s story through the dazzling panoply of choice offered by the internet.

What it all fails to realise is that pop’s fragmentation is nothing new, that the centre of pop collapsed way before we had access to the internet. More myopically & mendaciously though, all this clichéd retrospect fails to realise that being young isn’t feeling like you belong but feeling like you absolutely DON’T. Particularly to your own. Since my balls dropped, like most young people I realised that this ‘hive-mind’ shit was for old fucks to try and get a handle on you, impose a homogeneity on kids whose true variegations were too complex for such pat analysis. In the middle of the 90s when I was told by an editor that we couldn’t antagonise ‘the kids’ by daring to suggest that Oasis might be shite, I became even more convinced that any attempt to say what ‘the kids’ want/ need/ could-deal-with is inherently flawed and borne out of a patronising underestimation of how resistant to ‘the market’ kids can be.

It’s been ever thus. Such numb-nutted assumptions about kids’ cultural habits still stalk the pie charts; multi-platform brand dashboards and front covers of what the mainstream think about pop and pop history. But what’s appalling is that these formulations of the past have now hardened into consensus, to the point where if you dissent you’re somehow being a needlessly confrontational snobby cunt. Sometimes this gets tied in with class, usually by middle-class cultural historians who assume that working class taste operates en masse, who won’t allow the working class to deviate from the proscriptions and limitations imposed on their cultural history from above, let alone create things entirely outside of whatever prevailing flava they want to crobar them into.

When I wrote about the Stone Roses for the Quietus in 2009 it was suggested by many poopsockers that I was simply being a snotty elitist bastard (all true but duh, I’m a music writer) for pointing out the other stuff that came out at the time, that if I wasn’t monkey-strutting/wearing a wicket-keepers hat or e’d off my tits on a weekly basis I somehow wasn’t even there in 89.

Likewise this year a whole heap of lumberjack-shirted lies are getting reinvoked in service of yet more rockcentric remembrance – always when it comes to the retrograde rearranging of rock criticism it’s assumed that all of us were in thrall to who was the ‘biggest band’ back then, that we were all looking for the same fix, the latest spin on the old boys-with-guitars story.

What if some of us had no interest in that shit? What if some of us were coming at the 90s not looking for a great new band who could unite us but seeking out those producers, those underground crazies and hip-hop collectives and pop freaks and electronic circuit benders who could precisely speak to our growing sense of disunity, our isolation from the music industry’s old motifs, our exploration of music that went beyond being part of anything bar it’s own blazed trails and trajectories?

If the bands of the early 90s frequently were inspired by 80s bands, what if we as listeners had similarly been tripped out by rock’s re-emergence before it became the main story again? If you listened to Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr, Butthole Surfers, My Bloody Valentine, Loop, Throwing Muses, Pixies, Talk Talk & Young Gods in the late 80s Nirvana sounded like a step backwards, and not even in a retro-but-exciting way like Mudhoney did. If you were engrossed in Depthcharge, Jeff Mills, Front 242, Suburban Base, Prince Paul, The Bomb Squad & the Ragga Twins why the fuck would you care what a bunch of leather-trousered flower-shirted Stones-obsessives could cook out of their immaculately correct libraries and the ‘dance music’ they were so dilletantishly dabbling in?

There’s an assumption in the revisionism going on 20-years from 91 that everyone arrived in the 90s wanting & waiting for a band to conquer all and define it’s era. But many came to the 90s armed with an entirely different set of perspectives on music beyond the search for that year’s big rock monsters or most brand-defined moment (what an awful lot of the Nevermind recollections are conveniently ignoring is that for a lot of rock fans Use Your Illusion & "The Black Album" were far more defining, yet equally damaging records from 91). We weren’t all the fucking same and we didn’t all need Kurt Cobain. In fact many of us entirely resisted this bundling together of ‘youth’ under a musical banner.

By 1991 for a lot of us, rock didn’t matter any more. It was the routes and paths that allowed us to step free of its macho bearhug-hold that interested us the most. The most dizzying moments of drone in Sonic Youth & MBV, the most free-form passages of din in Zoviet France & KK Null & Jim Plotkin & Labradford & Main. The moments where rock bands and rock people admitted defeat and started to explore the low end intrigue & the dissaperance of ‘persona’, in the repetition & heat of the darkest hip-hop and dub and techno and ambient isolationism.

It’s not merely dis-ingenuity that makes 91 for me not the year of Nevermind but the year of The Low End Theory, What Evil Lurks, Play More Music, Death Certificate, Breaking Atoms, Reggae Owes Me Money, A Wolf In Sheep’s Clothing, Apocalypse 91, Mr Hood, Cypress Hill, Penicillin On Wax – these were the albums that bullied my time, that reflected my mind, that populated and soundtracked the spaces and wasted-times of 91 far more than any rock band could manage. The only rock that I let in in 91 was probably Spiderland, Frigid Stars, Loveless, Real Ramona and Yerself Is Steam, because even then you could sense a steady dwindling of the possibilities that seemed so alive in 88 & 89, the beginnings in Screamadelica of the essentially laddish revisionism that’d lead to Britpop.

Britpop’s rise found itself horribly mirrored in a growing cowardice amongst the music press, a fear of missing out on what the ‘kids’ were down with. There was an assumption that the kids could only ever be in to traditional band-structures and music. This was the dead-end that ensured black musicians would never be on the cover ever again unless they were tied to a chair and gagged. The dead-end in which PR & consensus finally and fatally won the war over young minds. The dead-end of faint nationalism that still endures today, that ensures the current mindfuck-games being played by government about being ‘English’ are allowed to sally into young minds unprotested by anyone involved in pop.

If we’re gonna look back let’s widen those eyes a little, look at stuff that expanded rather than atrophied what it meant to be making British music. I recall stuff that was fearless, I recall stuff that only looked back to find a spirit of resistance to the present, a spirit that could forge a possible future beyond playing 60s/70s dress-up. I recall music that was nigh-on ignored throughout this period. A few British bands who offered totally different possibilities for music, for British pop, for the relationship between the guitar and sound, for the future of recording, performance and listening. Don’t expect the Guardian to mention them much, they weren’t cockney heel-clickers, northern mouth-breathers or Seattle smackheads. They and the music they made still refuses to be crobarred in with any nostalgic summations of an ‘era’. But the music they made, now mainly forgotten, was some of the very best of its era. It reflected the fractured urges and yearnings of its times politically & personally far better than anything you could tag as being part of a movement. These bands may have shared stages and fans, but could never be called a ‘scene’ because. At the root of their music was a retreat into the shadows, a focus on musical explorations that were absolutely disinterested in external success.

At the time it was hard to get this stuff heard over the din of editors clamouring for Echobelly & Shed 7. Right now, this music, by outfits as long-lost as Disco Inferno, Pram, Lull, Scorn, Insides, Bark Psychosis, Laika, Movietone and Flying Saucer Attack, speaks louder than ever. It obliterates the stuff you’re currently being told was ‘happening’ back then. It even obliterates much of the new noise being pootled about right now.

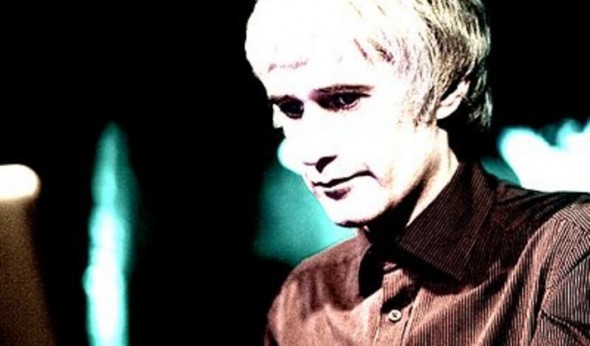

A good place to start with this non-scene, this forgotten crew of people spat out by the 80s but intent on not repeating its worse excesses and mistakes, is Main, because their founder, Robert Hampson bridges that gap between the late 80s reinvention of rock and the exploration of those desolate ruins these bands embarked on in the 90s. Its also worth speaking to Robert because he’s back in the fray, reconvening Main for a new millennia, playing live soon in Europe & the US, picking up the lost traces and possibilities and hungry to be back in the fight.

As founder of Loop, Hampson was right in the thick of rock’s revitalisation in the late 80s. He was aware that the rock Loop were making had coded within it the possibilities for its own annihilation. Main, the project he started after Loop’s 1990 dissolution was a chance to explore those avenues the more structured band dynamic of Loop had not allowed. Speaking from his home in Paris, where he has retreated into a bliss of composition and acousmatic music-creation after Main’s final break up in 2006. He admits there were Loop tracks that hinted at what he ended up exploring so dazzlingly as soon as that band had fallen apart.

“I think tracks like ‘Circle Grave’ (B-side of ‘Black Sun’ 12”), elements of the Fade Out LP, which had big guitar tape loops, elements of A Gilded Eternity – ‘Shot With A Diamond’ especially – all had shades of Main. The thing that maybe people don’t know about me or have forgotten, is that I was making actually a lot more (dare I use this term) experimental music before Loop. In the early 80s, the UK music scene was far more eclectic than you could ever imagine now. I had no fear of going to see Cabaret Voltaire one week, 23 Skidoo another and then happily be at an Orange Juice or Aztec Camera show the week after that. Maybe that’s more to do with my personal tastes, but I’m so happy to have been around at that time. There’s no rose tinted aspect to it, it simply was far more interesting then. All those great post-punk bands that just grabbed at various musical styles and made some new ones. People forget that Cabaret Voltaire were as much influenced by the likes of James Brown as well as William Burroughs or Brion Gysin. For example, I could see a Fire Engines show and get all the funk references as much as the Dada or Beefheart ones. So, that in turn had a huge effect on me. I’d buy a Teardrop Explodes record on the same day I’d get Cabaret Voltaire or The Pop Group.”

So even before Loop, you were making your own music?

Robert Hampson: Yeah, my friends and I started getting into recording, eventually on Portastudios, but my first recording device was a ghetto blaster with 2 inputs on it. I’d make hours of drone type material with short-wave radio and Bass guitar feedback. No mixers, just line inputs and bad overdubbing. All the Bass on the left channel, all the noise on the right, then dub it onto another cassette player in mono. We all did it. Very self-indulgent, but in that, I learned a lot. By the time I could actually afford to buy a Portastudio – over £600 then, which was an absolute fortune – I was primed. So in almost rejecting that more experimental side of me when I started Loop, it was somehow always was there, but hidden under the surface, until it came up for air again more completely with Main.

What about being in a band eventually became frustrating and necessitated Loop’s death & Main’s birth?

RH: My biggest problem with Loop in the studio at any time was that we just never had enough actual studio time due to funds. I think that was the biggest factor in me feeling I was cutting corners in the terms of sound. It didn’t help in experimenting. It was then I knew that I absolutely had to have my own studio, to have all the time you needed to fully realise the sound that you had in your head and to transfer it onto a piece of tape. I loved being in the studio – it was where I was most comfortable – I still love it to this day, I’ll never tire of working with sound and exploring all possibilities, but to do it well you have to have time… that is more important than money. Time.

Was A Gilded Eternity the straw that broke the camel’s back in terms of your frustrations with playing in a band?

RH: Making A Gilded Eternity was difficult, it was the beginning of the end for Loop, I see that now. I knew at that time we were doing something in changing the dynamics of Loop (always a good thing of course) but also I was feeling frustrated with wanting to change it so dramatically that it may have been to the detriment of the other members… and I never wanted to harm the others’ feelings at any time, we were a band after all, and those who know that when you are in a band, it should feel like a gang… and that’s it in a nutshell. Maybe I should have been braver and said to the others, let’s take all the rock out… completely. In hindsight (always wonderful 20-years later) they might have said yes, let’s try it. But again, two weeks to record an album is not enough to make you that brave… in my mind anyhow. But after that, the story wrote itself and not so long after, I’d had enough. Along with other elements, I knew I had to move on and become very self indulgent to get anywhere near the sounds I was hearing in my head. Soon after recording what became ‘Hydra’ and ‘Calm’ (mostly recorded on a portastudio and overdubbed at House In The Woods) I asked my manager at the time to collect funds from publishing and Beggar’s Banquet to build my own studio, I wasn’t going to be happy with any other way. So, for quite a long time, I had a fully functioning 24 track studio in my bedroom in a tiny one bedroomed flat. My poor girlfriend at the time, she really was an angel… bless her to put up with all of that.

A scientists lab?

RH: Yeah. This was years before computers as we know them now… just a huge desk, multi track machines, samplers, rack mount gear… everywhere! [laughing] Now, it’s just a laptop ,some very expensive recording devices and two speakers. How times have changed. But I really miss that analogue gear, really miss it. Very creative times then, with myself and Scott (Dowson), loved every hour after hour after hour of infinite recording and mixing and mixing. [Laughing again] The life of an anal retentive is not an easy one!

What was clear when Main arrived with the stunning ‘Hydra’ and ‘Calm’ 12"s was that whilst we were being told that grunge meant ‘rock was back’, those of the generation that inspired grunge had already moved on. I remember when I used to listen to Main hearing things that reminded me way more of dub, jazz and hip-hop (and also the crushing bliss you added to Godflesh’s work on Pure) than I ever got in Loop – there seemed to be an interest in the low-end way more than there was in Loop, the beats had a new precision and punch thanks to the drum-machine basis – was I being stupid or do you think Main reflected your real musical tastes/interests beyond the limitations of what Loop could allow you to explore?

RH: Well, the low end was there in Loop – but with Main, the bass really kicked in… being also very important as a rhythmical element, because I was desperate to remove known rhythm such as drums. I wanted the rhythm to come from more abstract elements. I loved hip hop and everyone knows my real love for jazz and especially dub. I always tried the dub side with Loop too, but it really lent itself to the more abstracted sound of Main. One thing I really wish we had done with Loop was get Adrien Sherwood to produce or mix something. He sat in on some mixing of A Gilded Eternity one day at the Mute studios – he actually worked out the delay time signatures for ‘Shot With A Diamond’ – and I was just sitting there thinking ‘Ask him…ask him’ but I was so in awe, I just wilted like a friggin idiot. I’m actually very shy, which doesn’t help. My happiest Loop shows were with Tackhead Sound System blasting it before we came on. I talked about it with Mark Stewart and Gary Clail at times and they both said we should have done it. A sorely missed opportunity. Ah well…

Would you say beyond your musical impulses for self-indulgence that in a personal sense you wanted out, out of the rush and extroversion of being a frontman?

RH: To a point, yes. As I have said, the studio is really my dream environment. It is THE instrument, the essence of everything I do. Without it, most of what I have done would not be what it is. I’ve always like to have the live and studio dynamic very separate. I always wanted the Loop records to reflect that. Certainly, we’d have never been able to create the studio guitars of Loop live, unless we had another 10 guitarists. But I never wanted that either. I guess you could say I have reclusive habits, I do actually love being alone and I’m the only one that I don’t have trouble communicating with. [laughing] But it was very important to work with Scott and we were for a long time completely on the same wavelength. I was very sad when he decided to leave, heartbroken in fact. Because after the Hertz project we were really stretching the very notions of what Main was about… I was desperate to go further with my good friend and co-pilot. So, after he left, I guess I thought it best to just continue by myself, but it wasn’t a good time for me. I was also having quite a lot of problems in my personal life and things were just not gelling.

Of course, at those retracting regressive times in the 90s people trying out new rather than tried & tested ideas in music were getting increasingly marginalised, what could you call yourself? A guitarist, a musician, a band, what?

RH: Well crucially, a lot of us didn’t care by then. I probably alienated 90% of whatever fan base I had left by then, but I’ve never regretted that. I really found my feet after a wobbly period and that’s when it got really interesting. Of course, it cost me a lot in the terms of Beggar’s letting me go, but I wasn’t entirely shocked. They were very brave to put out a lot of those Main records and I’m very proud that they did. Kudos to them for that, I’ll never slag them off. I’ll never entirely know what to call myself as in terms of what I do. Composer sounds too pompous. Sound Designer – yeah, everyone with an elastic band and a laptop thinks they are a ‘sound designer’ nowadays. So, I vote for compositional sound now. I hate categories implicitly, but you have to tell people something. Most of the time when I explain what I do to people who may not know me or the field I work in just look at me as I’ve just jumped out of a UFO anyway. It’s a tough one to crack without sounding like a flaming egoist.

It’s perhaps pat to see the arc of Main as a steady removal of ‘rock’ from your music but even on ‘Hydra’ and ‘Calm’, Dry Stone Feed and Firmament it was like you were laying down seeds of rock’s demise…

RH: “I sincerely hope so because this nags at me more than anything. [Laughing] Yes, the original idea for Main was to just completely change the dynamics of what came before i.e. Loop and in that simple fact alone, there was the destructive – and I mean destructive – notion of just rubbing the guitar out so it became a smudge rather than a line drawing. Yes, I will not lay claim to be the originator of that thought, Keith Rowe of AMM was doing that before I knee-high to a grasshopper, but I wanted to do it with much more of a modern approach and also to try and not copy the characteristics of how it was done on the improv scene.

I didn’t want that, I’ve no interest in copying that… I tried to do it differently. ‘Hydra’ and ‘Calm’ were the tail end of Loop – the comet’s tail so to speak. A couple of those tracks would have been Loop songs I think if we’d carried on. But I think the real issue with them are the tracks ‘Suspension’ and ‘Thirst’. That’s where I really understood where it was going to go. I liked the fact we still did structures that could vaguely be called songs, but at the end of the day, those two pieces were very important to how Main grew. They were the seeds. I remember thinking that I wish I could build my own guitar and have it not look like a guitar – I hated looking at the things, which indeed never helped my conflict with still wanting to use them as sound making devices. So, I should have spent money and just gone all out and had something made that had the basic needs of what I was looking for. But I didn’t, because I was too in awe of recording and just wanted to record and record as much as possible. Nobody saw what Scott and I were doing with guitars at that time so it didn’t matter what they looked like… and it was the cheaper option to carry on with what we had.”

As Main progressed through the stunning Ligature remix LP (wherein such like minds as Paul Schutze, & Jim O’Rourke rerubbed Main into strange new shapes), the devastating, sprawling Hertz project and the sequels to Firmament, their sound’s traceability to source, along with the precise place of the unmistakeable grooves they rotated around, became ever-more mysterious and engrossing.

RH: I loved the fact that people questioned at the beginning – is this from a guitar? I loved that. Apart from when it was reviewed it was maybe a synth, which used to really get my blood boiling! But then… after a while, even when it was evident that the sounds were in fact concrete sounds or field recordings that couldn’t possibly be a guitar, the reviews still hung on to the fact that it was still guitars and people still mentioned Loop every bloody two minutes. So, even after the very conscious effort of distancing ourselves (Scott was still involved at this point) from guitars and trying to really make them so abstracted that it really didn’t matter where the sound came from, they were still the focus point. After Scott left, I abandoned them altogether and yet still… they were always mentioned. My own legacy was repeatedly snapping at my heels and I couldn’t escape it. So, my only defining attitude was to say, OK, let’s really make a point here and stop all this guitar nonsense once and for all and stop Main. Maybe people will finally get the point. In most cases, they didn’t [laughing] and it’s still a chain around my neck!

So why return to Main? Why not something entirely new?

RH: My normal motto to myself is ‘Always Forward’ but in this, I’ve adopted the notion that I may be in a cul-de-sac (not in a creative sense I must add) and need to reverse a bit to get back on the road. After the last 6 years of being ‘solo’ and working much more on (for want of a better word) more academic-styled music, I had realised I hadn’t really worked or collaborated with anyone and I missed it. So, I had the idea to resurrect Main and make it just that. A project I can involve other friends and artists that I admire and try and create something fresh. I lay my hand on my heart and say I stole the concept from my friend David Jackman and his Organum alias. He has his solo works – as do I – and he has this project which over the years has a flotilla of like minded souls who dip and out to help flesh out the sound. I really like that concept and feel happy enough to refresh Main with those ideals. I hope it works, but it’s early days yet. I am currently working with Stephan Mathieu on this and it’s gently brewing into a nice concoction I must say. So, in essence, it’s not Main as people would know it, it’s like a part II and everyone knows how I love ‘parts’!

Do you feel Main got their due either during their tenure or since? Was ‘getting your due’ ever a motivation anyway, either during or since?

RH: This is really hard to answer without it all sounding overblown or egotistical beyond normal levels but no, I don’t think we got our due in the sense of how it (and a few other bands at that time) changed the face of musical approach, wilfully being experimental… but simply put, maybe people just didn’t ‘get it’ ? Maybe it’s taken a good few years for it to sink in and people are now getting interested in that style again, going back to the roots so to speak. Why would I have gone on exploring to much further realms if I really cared only for money and fame? Defining my signature and just searching for my own perfections. I’m still searching by the way.

I presume you have played guitar at some point in Main’s absence – but, how did it feel strapping one back on?

RH: No, I seriously didn’t pick up a guitar in almost 13 years. Would never look at them in stores, never dreamt about them, never relished anyone else’s. Just simply did not care about them. When others would wet dream over a certain vintage model, my gaze was always on a lovely microphone or tiny portable mixing desk (I hate carrying luggage, so the smaller the better).

Seriously, I just didn’t even think about them. I live near Pigalle in Paris and more often than not in the last year, I realised that I was getting a bit hot under the collar for guitars again when I passed on of the many guitar shops there. I started just wanting to get a beautifully made boutique Fuzz pedal (didn’t exist in Loop days) and plug in a guitar and just make a wall of noise again. Nothing to do with a mid life crisis or Main at this juncture, just that I wanted it to be suddenly be very, very simple again. I still have yet to achieve this ambition of a very noisy project, but it will arrive eventually.

So, I got up the nerve to buy myself a new guitar (as I had sold all my old ones), got some nice new boutique fuzz pedals (my new obsession) and just quietly dipped my toe back into those waters. As for it’s use in Main? Well, all I can say is that there will be the familiar old head scratching as to whether you can recognise them or not. They won’t be slung over my shoulder in Main, just laying on a table… vibrating. But I do hope to do something as I said…with it slung over my shoulder and standing in front of an amp, making ears bleed for a bit, I’d like that a lot. My attempts to join Neurosis have fallen on deaf ears. [laughs]

Who will be into Main now?

RH: I have no idea. I still get people come up to me and say how much they enjoy Loop and Main and how it has meant to them. Some people are not old enough to have seen Loop, some even to have not seen Main when Scott was in the band, but for them to approach me and say these things is very nice. I get embarrassed and start staring at my shoes, but it does warm my heart and I hope I don’t let anyone down when I don’t really have much to say to them apart from Thank You. There will always be avenues for Main live, even if I have to do it solo – I think it is new, it’s just a name after all, but one that I hope evokes good feelings enough in others to come on over for Part II. I’m always looking new, I think more people should be looking for new. We need more new.

Select Main discography:

Hydra-Calm (1991-92 Beggars Banquet compilation)

Dry Stone Feed (1993, Beggars Banquet)

Firmament (1993, Beggars Banquet)

Motion Pool (1994, Beggars Banquet)

Ligature (1994, Beggars Banquet)

Firmament II (1994, Beggars Banquet)

Hz (1995/96, Beggars Banquet compilation)

FirmamentIII (1996, Beggars Banquet)

Deliquescence (1997, Beggars Banquet)

Firmament IV (1998, Beggars Banquet)

Information about Robert Hampson, Loop, Main, reissues, new records and live performances can be found by visiting the At The Surface facebook page

Next week: New Clothes For The New World – Disco Inferno and the 5 EPs