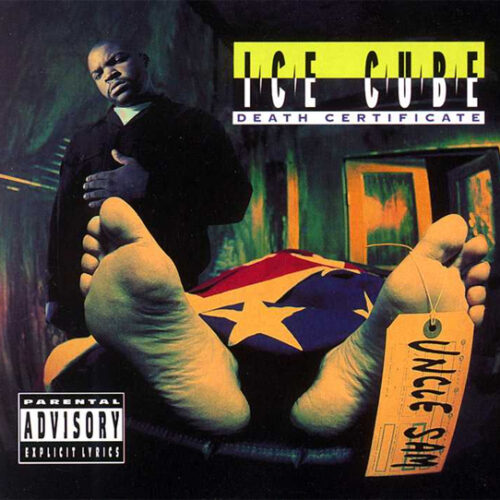

Classic albums are supposed to be celebrated, but Death Certificate doesn’t permit unqualified responses. It’s a record made by a young man as talented at needling his listeners as he was at constructing and delivering some of the angriest lyrics in the hip hop canon, and is impossible to love without qualification. If you’re not offended by a significant portion of it – no matter who you are, whatever your background – you’re not listening properly. Just about the only universal reaction Death Certificate generates is one of awe at the 360-degree ferocity Ice Cube maintains for its hour duration.

A singular musical statement, Death Certificate comes from a singular era, and whatever level of understanding we’re permitted can only be reached through thoroughly replacing the record in its complicated context. Although he’d pioneered the art of outrage as a preternaturally gifted teen, writing most of the rhymes for his NWA bandmates as the group took knowledge of Los Angeles’ gang wars global, Cube raised his game after he quit the band following a row over money. The group laughed at his solo ambitions and told him he’d never be able to carry off an album on his own; stung, he over-compensated, temporarily relocating to New York and teaming up with the Bomb Squad for his debut.

AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted was a meeting of musically aligned minds. The production team – the brothers Hank and Keith Shocklee, Eric ‘Vietnam’ Sadler and, under the alias Carl Ryder, Public Enemy leader Chuck D – were in the middle of a run of all-time classics (Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet, Son of Bazerk’s blistering Bazerk Bazerk Bazerk and AmeriKKKa’s… were recorded in overlapping sessions during 1990), but Cube and his production cohort, Sir Jinx, proved strong enough personalities to impose their own musical vision onto the Bomb Squad’s densely layered aural signature.

The partnership had begun awkwardly – Cube and Jinx were handed a crate by Sadler and told to not come out of the Squad’s warehouse-like record library until they’d found the samples they wanted to use on the album – and sessions, conducted overnight while work proceeded by day on Fear of a Black Planet and with Chuck, Hank and Keith only intermittently present, sometimes felt like an afterthought. But Cube’s single-minded devotion to making a record that would blow everything he’d done with NWA out of the water, and the dirt-encrusted funk that Jinx added to the often mechanistic Bomb Squad sonic stew, gave the resulting album a unique power and potency. It set the pattern Cube was to follow – daring his audience to stand with him, no matter what he said. He repeated the trick with a follow-up EP, Kill at Will, which included a couple of remixes from the Bomb Squad sessions but, in the Jinx-produced ‘The Product’ and the reflective yang to its belligerent yin ‘Dead Homiez’, showed the way forward. The next record would be self-contained, and – even though there was little sense of restraint evident in the Bomb Squad sessions – unconstrained.

Death Certificate‘s creative independence may be its most important and least celebrated legacy. I have a vivid memory of playing a pre-release cassette copy of the record to DJ Marga, producer with the British rap group Katch 22, whose first reaction, beyond grins and appreciative nods, was to exclaim, as if personally sharing in the triumph: "I knew they could do it on their own!" In 1991, nobody was talking about East Coast/West Coast beefs, and the idea of hip hop production having a second epicentre worthy of comparison to New York wasn’t fully formed, never mind widely supported. The Bomb Squad’s dominance over the hip hop landscape was almost total: producers were either influenced by them, in thrall to them, or lying. Dr Dre’s production for NWA had borrowed heavily from the Shocklees, Chuck and Eric – ‘Fuck tha Police’ even used the same Marva Whitney sample as ‘Bring the Noise’ – and despite changes evident in his work on Above the Law’s (brilliant, oft-overlooked) 1990 debut Livin’ Like Hustlers and the second NWA album, Efil4Zaggin, the signature style Dre would mint on The Chronic was still a work in progress. The idea that Cube, Jinx and cohorts the Boogiemen could make an album that stood up sonically next to the giants of the East, and to have done so without looking beyond their own camp, would be of immeasurable, inspirational importance to rap artists around the world who had previously felt – with some measure of justification – that anyone from outside the hallowed Five Boroughs had no chance of getting a fair hearing. Death Certificate proved to hip hop artists around the globe that Rakim was right all along – it wasn’t where you were from that mattered, it was where your art was at.

But it’s the record’s content that means it retains its position at or somewhere near the list of most offensive and contentious albums ever made. His time in PE’s orbit coincided with the Professor Griff/Washington Post controversy, but Cube already had an instinctive flair for writing from within a siege mentality; yet on Death Certificate he wasn’t responding to outside criticism and defending himself by lashing out – he provoked what he knew would be negative critiques with pre-emptive verbal strikes against any target he could think of, then wrote from a defensive position inside this self-constructed crisis. Broken down in that way, the record can seem self-serving – and there is a certain grandiloquence or megalomania inherent in such an approach. But the risks Cube took were every bit as great: Death Certificate is a record that seems to delight in taking every demographic in the (still emergent, in 1991) Ice Cube fanbase and constructing at least one song with the purpose of provoking them into abandoning him. We’re often deceived by the curl of the lip – that voice, among the most remarkable instruments in hip hop history, gives his lyrics an almost sculptural physicality and manages to recreate audibly the furrowed brow and heavy-lidded scowl Cube adopted in every photo shoot – but the approach bespeaks something other than all-out bullish self-confidence. It’s almost as if a secret internal fear of rejection caused him to try to test the strength of every alliance by pushing it to breaking point from the outset.

The album was designed for vinyl, the first half designated ‘The Death Side’ and the flip ‘The Life Side’. In the spoken intro, Cube defines these as, respectively, "a mirrored image of where we are today" and "a vision of where we need to go". And it is here, within the record’s first nine seconds, that the problems begin to mount. Without this overarching concept, the excesses of some of what follows can be more easily excused; with it, the stuff on side one which deliberately courts outrage can be read as political and social critique, allowing its bilious poison to be drawn a tad; but with the incendiary material stacked up on side two, Cube’s apparent claim to be offering solutions intensifies each objectionable verbal volley.

Within the framework he gives us, it’s possible – though still pretty difficult – to excuse the excesses of a track like ‘Givin’ Up the Nappy Dug Out’. Context, again, is everything: the prelude to the song is a row between a surly Cube and the father of a girl whose doorbell he’s just rung. The string of sexual insults and degrading imagery that follows is stomach-churning, no matter how clever the wordplay and how irresistible the Boogiemen’s appropriation of Booker T and the MGs’ ‘Hip Hug-Her’. But that intro changes how we view the song: we’re not supposed to identify with Cube’s character, we’re supposed to see him and his idiocy as the juvenile rants of a teenager given a verbal smackdown by someone else’s parent. He may be full of snarl and smut and spit, but all he’s doing is shouting insults at a closed door. And the appearance of the song on the ‘Death’ side of the album – as the part of the whole which is supposed to exemplify the problems of contemporary society, not the part that presumably identifies and advocates ways forward – is crucial. The violence, misogyny and hatred are deployed for a purpose. But it’s hard not to hear a certain relish in the delivery, making the song, like so much of the album, desperately difficult to take.

Cube’s problems really came on the ‘Life’ side. Two tracks in particular attracted outraged public opinion, both of which were removed from initial pressings of the record released in Britain. (The UK distributor of Death Certificate, Island, had been stung in the summer of 1991 when Efil4Zaggin had been deemed obscene in Ireland and copies impounded; by the time Death Certificate was released, the appetite for similar risk was nil, and sanitising the record by removing the two tracks that had caused the most controversy in the US presumably seemed pragmatic. The wonder is that they released it at all, given the level of offence the record as a whole was clearly designed to provoke, and the limited prospect of profit back when US hip hop albums were available as expensive imports for months before the UK pressing was made available, ensuring that everyone but the merely curious had already bought it in its unexpurgated form.) Of the two, the closing ‘No Vaseline’ really ought to be seen outside the Life/Death concept – it’s preceded by Cube’s stage whisper in which he reminds himself that he’s forgotten the minor matter of having a pop at his erstwhile contemporaries ("Damn – forgot to do sum’n. Let’s see… Oh, yeah: It ain’t over, motherfuckers.") and is an afterthought appended to the album rather than an intrinsic part of it. But the other – ‘Black Korea’ – is integral.

‘No Vaseline’ is the only part of the album where Cube sticks to hip hop’s codes: the dis track had long been a staple, and after the critical and commercial success of AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted had failed to shut NWA up (they’d taken potshots at him on their 100 Miles and Runnin’ EP the previous year) it was inevitable he would retaliate, and that he’d do so in stark, verbally brutal terms. One of the most lauded battle records in hip hop history, it nevertheless is formally conservative: the trope Cube repeatedly deploys is to allege homosexual relations between his former bandmates and their manager, Jerry Heller, who Cube believed was complicit in what he felt was the royalties rip-off he’d experienced. He lands jabs on Dre, Yella and Ren, but holds his heavier blows for Heller and Eazy-E – the only one of the outfit with deep and durable gang affiliations. In a battle-rap masterstroke he takes Eazy’s most memorable act of subversion – turning up to a Republican fundraiser with the first President Bush, evidently invited by White House staffers under the mistaken impression that anyone owning a multi-million dollar business would be a shoo-in for a campaign donation – and subverts it himself, rapping, repeatedly, "I never have dinner with the president."

The controversy around the track seems misplaced: not even Heller – who hates it with a passion – believes it was anti-Semitic. What surely fanned those particular flames was not the track so much as Cube’s October 1991 public plug for a book, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, published by the Nation of Islam, that purported to be ‘proof’, in the words of Jews themselves, that Jews were architects and principal beneficiaries of the slave trade. In the preface to a 1992 booklet concisely refuting the key tenets of …Secret Relationship…‘s supposed scholarship, Bill Adler – Public Enemy’s long-term publicist, who described himself as "a Jew by birth and education, and a rap scholar and activist of longstanding" – characterised Cube’s endorsement as "the socialism of a fool". In the years since, …Secret Relationship… has been thoroughly discredited, shown to comprise vast chunks of material taken from the notorious forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Surprisingly, Cube still considers it an "interesting book. I don’t take any books as fact – all books are opinions. I’ve read a lot of interestin’ books between now and then, and I take ’em all the same way," he told me in an interview in 2010. But over the years he has allowed himself to acquire some nuance: he won’t exactly admit that he’d do things differently a second time around, but he would, presumably, take a little longer to think when wading into certain choppy waters. "When you’re dealing with stuff like this," he told me, "you can’t – and here’s what I’ve learned – link everybody together in the same pot. You’ve got good black people, and you’ve got bad black people. You’ve got good white people and you’ve got bad white people. And so on, and so on, with every race, creed or colour. That’s just how it is."

‘Black Korea’, though determinedly ugly, seems to have been at least partially misunderstood. All of 46 seconds long, the track is basically a warning couched as a threat, aimed at Korean convenience store owners in LA’s black ghettoes, informing them that attitudes toward their black customers must improve if tensions between the communities aren’t to spiral into murderous violence. Cube argues it was never meant to advocate interracial violence, and claims that, in a meeting he held at his Street Knowledge production company offices with members of LA’s Korean community after the record’s release, he even earned some measure of begrudging respect from them ("They didn’t say that I was just sittin’ here lyin’, like I wasn’t talkin’ the truth," he told me in 2010. "They just didn’t like how I put it."). History seemed to somewhat vindicate the general tenor – the track was written after a black woman was shot dead by the owner of a Korean shop; and in the rioting that followed the acquittal of the four police officers videotaped beating black motorist Rodney King in 1992, Korean stores were targeted by black rioters – but it’s just as possible to argue that Cube’s record helped ratchet up the tension by verbalising and therefore legitimising thoughts that may have been held widely prior to Death Certificate but were largely kept private. There are no easy answers anywhere on this record.

What is undeniable is that by 1993, when Michael Douglas’s character protested over-charging by smashing up a Korean-run shop in a Los Angeles ghetto in Joel Schumacher’s film Falling Down, the issue had lost little of its controversy – but that movie’s UK distributors felt no apparent pressure to remove the scene before it was released. Cube had already embarked on his silver screen sideline with his acclaimed portrayal of Doughboy in John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood (a film titled after a track the rapper had written for NWA) and wasn’t surprised that Douglas and Schumacher were able to get away on screen with something he had been vilified for making a record about. "He’s a white guy mad at the world," Cube said in 2010. "It’s not as real as when it’s me talkin’ about real stuff. My record was really touchin’ the real-life problem – it wasn’t just a scene in a movie."

In this sense, Cube probably still views ‘Black Korea”s place on the ‘Life’ side as correct: looked at from one angle, he’s flagging up a problem and suggesting a way forward that can bring things back from the brink, albeit doing so in the most incendiary way possible. It may have overshadowed the wider, and very urgent, points he was trying to make elsewhere – the mortal dangers of promiscuity essayed in ‘Look Who’s Burnin”, which would begin to look like grim prophecy by the time he and Eazy were reconciled as the NWA mastermind lay dying of an AIDS-related illness; ‘My Summer Vacation’, which prefigured the franchising of LA gang culture as a deadly global export; and ‘Us’, the searing album closer, which excoriates American blacks for looking outside their community for solutions to their problems and presages the mainstream rap of the 21st century, which functions all too often as the marketing wing of luxury goods, alcohol and fast food companies – but ‘Black Korea’, and the furore it sparked, remains the distilled essence of Death Certificate. Certainly, while the record garnered responses Cube was expecting, the tracks singled out for outraged criticism surprised him.

"I knew the record was politically lethal," he said last year, chuckling. "I knew the record was gonna cause some controversy. But I didn’t think I was gonna get called anti-Semitic. That threw me off. It was like, ‘They think I don’t like a certain kind o’ white people?’ I got a problem with all the powers that be that got us in this fucked-up circumstance: I don’t care whatever religion you are. You know? I just hadn’t divided people up like that at that point. I was ready to discuss the whole record, and it was like it was caught on those two [songs]. That was kinda what I was surprised about. But, you know, it is what it is."