I’m no big fan of the band U2 became. When I was at school they represented everything I wanted to kick against: that smug black-and-white Joshua Tree poster, pinned to the wall of the fifth-form lounge, exuded carefully contrived and paid-for faux-authenticity that was supposed to represent some pinnacle of sophisticated musical taste among the bum-licking swots who lounged there (as opposed to the carefree oiks kicking balls about and practicing their bad breakdance moves in the cold Yorkshire drizzle outside).

And yet, I dimly – guiltily, secretly – remembered that there was once another U2. A young band that existed at the commercial end of post-punk, and that made records with a passion that seemed confused rather than calculated, awkwardly direct rather than fudged and pretentious, itchy and brash instead of ponderous and terminally tasteful. A band that fizzed and charged with youthful energy but also conveyed a clumsy melancholy, a Celtic twilight poetry; and I remembered how I’d thought that ‘New Year’s Day’ was the best song ever when I was 12, because it chimed with exactly the same mixture of inarticulate sadness and shivering, wide-eyed expectation that puberty frequently pitched me into, especially when wandering o’er hill and dale in the aforementioned Yorkshire rain. But by 15 I’d learned to keep this firmly to myself. You have to learn to rewrite your musical tastes and personal back-story pretty frequently at that age.

‘New Year’s Day’ came from the band’s third album, War. But it was actually the last strangled cry of an incarnation of the band that had peaked rather earlier; on their debut, in fact, released in October 1980. And while War still has its moments, and I’d certainly make a case for their second LP, the much- maligned October – a symphony of shouted doubt, all tumbling piano, undigested art rock and deep religious crisis – it’s Boy that absolutely captures the brash, adolescent energy of a bunch of naïve hicks from the Dublin suburbs, armed with a couple of Patti Smith and Television albums and the belief that they could change the world. Of course, the crash-and-burn aesthetic of youthful naiveté and romantic idealism can only really sustain you for one album; arguably U2 clung on to it for far too long, until it came to seem like a case of arrested development, an exercise in prolonged embarrassment. Really, after making an album like Boy, you should immediately split up and disappear, to be spoken of in hushed whispers in years to come as revered and mysterious cult artists with just this one pure and singular artefact to their name. What you certainly shouldn’t do is go on to become the biggest band in the world. That just isn’t cool.

But then, they were never cool, even when they were starting out. They were a school band, with a series of bad school-band names – Feedback, The Hype – before settling on the only slightly better U2. Awkward misfits who couldn’t, or wouldn’t, fit in, they started hanging around with a bunch of real freaks, cross- dressing Bowie victims and Artaud-reading art punks who, drawing a line between themselves and the rest of the community, called themselves Lypton Village. Lypton Village‘s Gavin Friday and Guggi formed the Virgin Prunes, one of the most fiercely experimental and confrontational bands of the period, who frequently performed alongside U2 on that early church hall and youth club circuit. It took guts to crossdress in 70s Dublin, and more to lambast the Catholic Church onstage while performing with severed pig’s heads attached to your groins. U2 may not have sought to outrage in the way the Prunes did, but the two bands had many shared aims and objectives, and one can picture them poring over their imported NMEs and Melody Makers, imagining the freak community waiting to embrace them once they reached London: “There we’ll fit in! There we’ll belong!“ But while U2 were seen as the local weirdoes in Dublin, in London they were greeted with suspicion for being too straight. And while it may have been a Lypton Village convention to take on a silly/surreal nickname, one can only wonder what possessed Paul Hewson and Dave Evans to decide that, from that point on, they were going to be known as “Bono Vox” and “The Edge”. You can almost hear a permanently beshaded Ian McCulloch muttering “knob ‘eds” under his breath, before he’d even heard a single note of their music.

Nevertheless, gauche as hell but wide-eyed and eager to learn, U2 threw themselves into the support-band circuit of post-punk London, borrowing and pilfering from a peer group that included not only the Bunnymen but Siouxsie And The Banshees, the Skids, Magazine, PiL, the Birthday Party, the Cure… and Joy Division. U2’s early Joy Division fixation is overwhelming: they recorded their debut Island single, ‘11 o’clock Tick Tock’, with Martin Hannett on the basis of his work with JD, and the follow-up, ‘A Day Without Me’, was actually about Ian Curtis’s suicide, coming wrapped in a sleeve showing a monochrome photo of a Manchester railway bridge, deliberately referencing Kevin Cummins’ iconic Joy Division photography. Shortly afterwards, Bono apparently paid a visit to Tony Wilson in Manchester and said that Curtis had been the greatest singer of his generation, and now that he was gone U2 intended to carry out his legacy – to finish what Joy Division had started and take it to the very top.

U2 intended to have Hannett record their debut album, but the producer withdrew completely after Curtis’s suicide; instead, Boy was produced by Steve Lillywhite. He was then very much associated with new wave, his slim CV including the first two Ultravox albums and the debuts from the Psychedelic Furs and Siouxsie And The Banshees. His influence on U2 was crucial, coaxing and encouraging the still-inexperienced band, who, rather than just knocking out their live set, were writing and experimenting in the studio. Adam Clayton in particular required constant coaching and nursing, yet his admittedly simple basslines are at the heart of the finished record, as vocals and guitars bounce and echo off each other within a sonic landscape mapped out by the single-minded rhythm section. Both Clayton and drummer Larry Mullen Jr play like they’ve never heard a funk or R&B record in their lives, but this otherwise utterly Caucasian-sounding record has a sense of space and texture that recalls the dub- reggae productions of the time. It’s rock music, but made strange by a kind of feral naiveté; often improvising lyrics at the microphone, Bono deliberately misses notes to unsettling effect, and his vocals are intercut with yelps and hoots, weird chanting and percussive whispers. The Edge responds not with preconceived riffs and chord sequences, but with tones and textures that reflect the emotional content of the words.

The album opens with its most enduring track, the second single to be culled from the set: ‘I Will Follow’. It’s basically ‘Public Image’ via ‘Hong Kong Garden’ but served sunny side up: Lilywhite adds the same percussive glockenspiel pings as he did to the Banshees’ track, while he Edge takes Keith Levene’s tunnelling, burrowing guitar riff from the PiL song and directs it outward rather than inward, spiralling up to open skies in contrast to how Levene pursued Lydon’s agoraphobic existentialism through ever-decreasing circles. And whereas Lydon was reclaiming the public and making it private, personal and exclusive, Bono takes a highly personal subject matter – his grief for the death of his mother when he was 14, just six years before – and somehow turns the sense of loneliness and abandonment into something inclusive and communal, celebratory even. It’s these tensions – between triumph and surrender, celebration and loss, introspective isolation and the tribal call-to-arms of the martially driven music – that give the song, and indeed the whole album, its power.

‘Twilight’ finds The Edge channelling another of his major influences, Television’s Tom Verlaine, over a pseudo-gothic Banshees beat, while Bono gulps out the title with all the glorious awkwardness of a young Billy McKenzie. Ambiguity isn’t a quality often associated with U2, but the lyrics to ‘Twilight’ are strikingly slippery and suggestive. Bono has said it’s about “the grey area of adolescence… when the boy that was confronts the man to be in the shadows.” But it’s hard not to read themes of sexual abuse into lines like: “My body grows and grows/It frightens me, you know/The old man tried to walk me home/I thought he should have known.” It’s even possible that the boy in the song has murdered the man who tried to molest him, and not only that but enjoyed it and gained some dark wisdom from the experience, before running home through the rain, soaked (in blood?) to the skin: “I look into his eyes, they’re closed/But I see something/A teacher told me why,/I laugh when old men cry” (note the placing of that last comma, from the lyrics as printed on the album’s inner sleeve: it changes the whole meaning of the sentence). Homosexual initiation by an older man followed by ritual murder as some kind of primal rite of passage? It’s one interpretation, anyway.

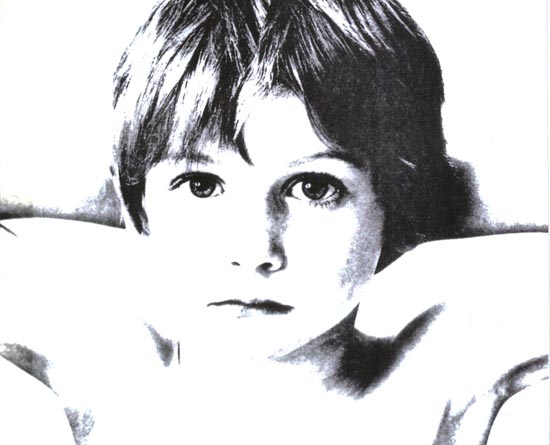

What is certain is that themes of coming of age, loss of innocence, adolescent passion and a first awareness of death and mortality so dominate the record as to make it a virtual concept album. From its striking sleeve shot (a black-and- white portrait of seven-year-old Peter Rowen, Guggi’s kid brother) Boy stands on the very cusp between youth and manhood, pure and apart, clean-limbed and untainted, yet ready too to assume the mantle of adult responsibility and sorrow. The early death of his mother left Bono no illusions that he could return to some comforting garden of prelapsarian innocence, and Boy is a farewell to childhood rather than a longing glance backward. But there are some qualities of youth that the band obviously wish to retain: the sense of possibility, the honesty and vitality, the energy and righteous anger. Some might say that U2 never have grown up, and certainly this album is the work of a very young band, singing about coming of age but still to reach maturity.

There are similarities between Boy and Generation Terrorists, the first Manic Street Preachers album; both were conceived by a self-contained, self-sufficient teenage gang, isolated from fashionable musical scenes but believing devoutly in rock & roll as a way to avoid growing up defeated and bitter; fervently resisting the corruption and compromises that adulthood seems to entail, at least in the communities they were raised in. Yet crucially, Boy lacks both the deep sense of self-loathing and the intellectual precocity prevalent in the Manics’ Richey-era work. U2’s distinguishing feature at this point was their almost unnatural positivity and idealism; their musical textures may well have sprung from the same well as the proto-gothic outfits of the time, but they stripped away the darkness and gloom, coming on romantic and exhilarating like some old 60s psych outfit instead. ‘An Cat Dubh’ sounds at points like a Celtic cousin of the 13th Floor Elevators’ ‘Roller Coaster.’ If every other post-punk band was reading Burroughs and Ballard, U2 were devouring Kerouac and Salinger, choosing emotional truth and gut instinct over rational argument and intellectual reasoning every time.

So ‘A Day Without Me’ finally rejects the self-destructive pessimism and negativity inherent in post-punk, highlighted – and for some, validated – by Ian Curtis’s suicide. U2’s love of Joy Division and respect for Curtis as a writer and performer remains, but the song refuses to acknowledge him as any kind of martyr and fights clear of his long shadow; by the coda, the sun has broken through and Bono’s closing “bah bah bah”s would sound more at home on a Teardrop Explodes song. On ‘Another Time, Another Place’ The Edge breaks into a Verlaine-like solo that nods to Magazine’s ‘Shot By Both Sides’ as Bono starts growling and speaking in tongues, his voice dropping a semitone out of tune as he does so. ‘The Electric Co.,’ about a friend who was sectioned and given ECT against his will, uses tension and release in a manner that’s appropriately convulsive, the music tightly-wound and brutally disciplined yet channelling a wild pagan energy.

And if ‘Out of Control,’ one of the band’s earliest songs, is a fairly pedestrian, Clash-like rocker, albeit one with the clean, ringing guitar sound of Generation X or the Skids, then ‘Stories For Boys’ gives the formula a twist, its music summoning stirring feelings and romantic notions of death or glory while the lyrics debunk just those myths of heroism and noble violence, decrying the easy emotional manipulation even as they expertly carry it out. Who says U2 can’t do irony? Alas, the album ends with a whimper; ‘Shadows And Tall Trees’ seems like a straightforward acoustic ballad that’s been plied with flanged bass, off-beat, echo-gated toms and Lillywhite’s massed glockenspiels in an attempt to give it a post-Joy Division makeover. But perhaps this embarrassed, shuffling fade-out is appropriate to the record’s evocations of adolescent awkwardness after all.

There is a parallel universe in which the cult Irish post-punk band U2 decided to call it a day not long after releasing their debut album. In this universe, a mild- mannered carpenter named Dave Evans still sometimes picks up his guitar and wonders about what might have been, and occasionally gets tracked down by wide-eyed fanzine kids, eager to ask about harmonics and tunings he’s long since forgotten. And the flamboyant, outspoken and unconventional parish priest Father Paul Hewson explains to the press for the umpteenth time that the money was just resting in his account, and wonders about that offer for the old band to reform and play at this year’s All Tomorrow’s Parties. But Clayton is still doing time after getting busted for dope again, and no one’s seen Larry Mullen Jr since his mid-life crisis, when he jacked in his job at the post office and took off for America on a second-hand Harley.

Meanwhile, the Comsat Angels’ twelfth album has just gone straight into the charts at number one. That could’ve been us, Hewson thinks, as he turns down the radio. Then he shakes his head and laughs.

Who do you think you’re kidding, Boy?