Where to, musician? In his magisterial work, Music In The Balkans, Professor Jim Samson traces some of the region’s musical traditions back to the expulsion of the Sephardic Jews from Spain in 1492. Samson sees the resultant Ottoman-Balkan musical heritage of the Sepharad irrigating two narratives of place: one of exodus and one of acculturation. Both narratives obviously employ music as an expressive force; whether to justify or entrench the “proper place” a group finds themselves in in the here and now, or as a powerful memory aid to cement the ties with the place the group should return to.

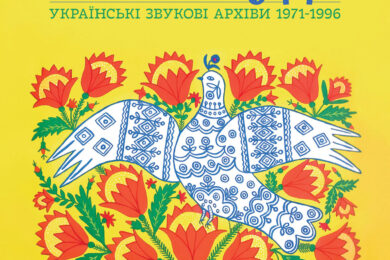

The idea of a “proper place” for people seems to dominate our times. It inveigles its way into many actions or expressions, however well-meant, or justified. Tied to narratives around memories of suffering or lived experience, and expressed through related forms of the arts such as music, it can be virtually impossible to argue against. A proper place is also suggested by Even The Forest Hums: Ukrainian Sonic Archives 1971-1996. With this superbly-curated compilation, Ukrainian post-war popular music is surely meant to be prized free of the monolithic and injurious stranglehold of Russian culture, just like Bruno Schultz and Nikolai Gogol are getting their new “proper place” in literature, or Kazymyr Malevych, Sonia Delaunay, Alexandra Exter and El Lissitzky are getting theirs in the fine arts. Of course, this is a good thing: in the context of the wider history, it is impossible to argue against.

The compilation casts a broad net – it has to, to encompass the decades that saw the Soviet Russian regime crumble and Ukraine gain its independence. Even The Forest Hums runs in chronological order, From Kobza’s “trad walz inflected” ‘Bunny’, released in 1971, to Ihor Tsymbrovsky’s wonderfully melodramatic chanson, ‘Beatrice’, from 1996. Along the way we get gems like The Hostilnia’s marvellously doleful rap, ‘Sick Song’, from 1992 and work by the remarkable Svitlana Okhrimenko from Sugar White Death. There are a lot of specific Ukrainian elements in the music: the collective Yarn uses traditional Ukrainian cymbals in their track, ‘Viella’, for instance. At the end of the booklet there is a dedication to Ukrainian artist Maria Prymachenko, whose house-museum was almost destroyed by a Russian missile in 2022. We know where we are in the world.

With this new socio-geographical repositioning in mind, Even The Forest Hums sits comfortably alongside other “Soviet / post-Soviet” releases from the past decade or two. Examples that quickly come to mind are the soundtrack to Soviet Hippies, a documentary tracking the Estonian hippy underground of the 1970s and 1980s, and its dealings with the communist regime. Then there’s Kosmos – Soundtracks Of Eastern Germany’s Adventures In Space. Or Paprikázz Fel!, a double album which charts the Hungarian beat and rock scenes of the mid-to-late 1960s.

Listening to Even The Forest Hums, we quickly find the duality which Samson mentioned, namely – and depending on where someone stands politically – how music is used to engage with, reconstruct, blindside, or merely avoid politics at its most shrill and overbearing. The Western concept of a music underground or alternative movement is misleading, as Bardetskyi quickly points out in his liner notes – that idea would mean the vested power accepting or tolerating a challenge to the status quo. The power of the ever-present pan-state label Melodia must be brought into reckoning here, as well as the local vetting committees, plain clothes spying missions and secret dossiers. There is plenty of literature on the subject. The Estonian polymath Kiwa, in an essay on his nation’s pop music of the Soviet era, lifts from the language of the time to show that “exaggerated searches for form” and “Western decadence” in the post war Soviet space meant trouble of one form or another, and usually led to a “balancing act on the border of the official and unofficial”. To be truly outside the system by making an open art-for-art’s-sake challenge to it could lead to a “grotesque and magical” situation. The famous Czechoslovak band of the late 1960s and 1970s, Plastic People of the Universe often found themselves negotiating this as they became “maybe the voice of mice in a labyrinth” mirroring a “claustrophobic and complicated” world, “too complicated to be communicable to anyone who is outside its walls.”

To begin with, the tracks on Even The Forest Hums outwardly conform to Kiwa’s blueprint, even if there is some Western decadence – and a British EMS Synthi 100 synth – in the Morodertastic ‘Dance’, by Vadym Khrapachov. The aforementioned Kobza’s immersion in Ukrainian folklore and traditional music is evident and surely no fusty cultural committee could ever condemn this gentle waltz. The groovy live track from the Oleksandr Shapoval sextet and the light jazz workout from Shapoval’s Vodohrai skilfully manage to sidestep the muffling of the rhythm section (which was done to reduce the negative influence of “capitalist” rhythms, an echo of the Nazi ban on jazz). If you want to hear a track with its feet in both camps, then listen to Kyrylo Stetsenko and Tetiana Kocherhina’s ‘Play, Violin, Play’ which flirts outrageously with decadent Western disco whilst being sufficiently martial in some of the vocals and beat. It’s so mauve…

The fluidity within this Soviet space for those less brazenly contemptuous of the regime than the Plastic People is often overlooked, however. Despite the repressive conditions, things, people, information, music, got over borders and created scenes and networks: like Laibach in Ljubljana, or Cluj’s ‘King of Records’, Rodion Ladislau Roşca. On Even The Forest Hums, the story of violinist Valentina Goncharova can be held up as another example. Born in Kyiv, Goncharova studied at the Leningrad Philharmonic, and was part of the local free-jazz and avant-garde scenes. She moved to Tallinn in the mid-1980s, and, with her husband, began to record remarkable sound improvisations on the Soviet reel-to-reel tape recorder, Олимп (Olympic). Goncharova’s track, ‘Silence’, is a magical, sprite-like piece of electronic sound that seems to hover above notions of time and space. Folk-like elements balance against sparse ambient effects that sound for all the world like a mic’d-up triangle.

With this in mind this reviewer can’t help but remember a quote from legendary Bulgarian poet and bass player Dimitar Voev, a person known for making highly personal music and lyrics that were openly critical of the Bulgarian communist regime: “one is born essentially apolitical”. Voev’s (obviously political) tennet is that it is often nurture, not nature that conditions us to behave as we do. We have to adapt. Travel, adaptation and clever ground-level interventions, all leading to a form of education through entertainment; essentially the role Robert Graves laid out in The White Goddess for the “gleeman”, the (pagan) wandering minstrel, who stood in opposition to the (eventually Christianised) court poet. The Ukrainian gleemen on Even The Forest Hums have to be the neo-hippy commune, Er. J. Orchestra, who were famous in 1980s Kyiv for their street theatre and spontaneous public jams. Their track, a gentle shuffle embroidered with flute and violin, is called ‘Tea Ceremony’ and has the same wandering spirit heard with Czech jazz masters Teagrass, and even a hint of the kosmische – think Witthüser & Westrupp.

Other adaptations, like the Radiodelo cut, ‘90’, have their feet firmly in the wider alternative musical world of the 1980s, where letters passed back and forth to like minded artists in the West. ‘90’ has a lot in common with the snotty punk collage of Nigel Simpkins’ ‘Times Encounter’, for instance. More post-punk spikiness can be heard with the first band of Gogol Bordello’s Eugene Hütz, North Wind. We are told their track, ‘Uksusnik’ (Vinegar) is “a downtempo Cossack march accompanied by Saigon rock guitars” but could be made by an Ultra band in the Amsterdam of 1980. Sugar White Death (also heard on Memory Leaks, the extremely informative 20 ft Radio vs The Quietus podcast series about independent Ukraine’s pop music history) are, surely, about to become everyone’s favourite Gothic chamber band, albeit thirty-odd years too late. Nothing can sound as spectral, or as enticing, as their track ‘The Great Hen-Yaun’ River’. The ending will catch you off guard, be warned.

Some of the music on this compilation defies time and place: Goncharova’s ‘Silence’ is one, and Kyrylo Stetsenko and Natalia Gura’s ‘Oh, How, How?’ is the sort of sound that regularly comes in and out of fashion (Kate NV, anyone?). Exile Iury Lech’s ‘Barreras’ is another matter entirely. The track is a sublime eight-minute long floatathon in the vein of Moon And The Melodies, and possibly the most arresting piece on the record, by virtue of its spare, but ever-giving sound wash.

Ultimately we learn that music is its own master; the art form takes many forms and encourages people to follow the strangest paths, despite the narratives we build to justify ourselves, and our place in the world.