For this feature, we asked tQ’s esteemed contributors to pick their favourite unmixed genre compilation album, the records that introduced them to hitherto unexplored corners of the musical map. For some, their albums of choice took them to realms that were entirely unknown to them – Venezuela’s burgeoning community of experimental musicians in the 1970s for example, or the beautiful traditional music of the Caucasus. For others an LP caused them to entirely reevaluate a genre, turning metal or experimental electronica from an impenetrable other universe into a welcoming new world to be explored. Some are simply excellent records.

Such is the joy of the humble genre comp. Below you’ll find some of the very finest ever released, a top 40 which takes in metal, hip hop, folk, drum & bass, kologo, disco and more, and spans almost every continent on Earth. We hope you enjoy this collection of the finest collections.

Patrick Clarke

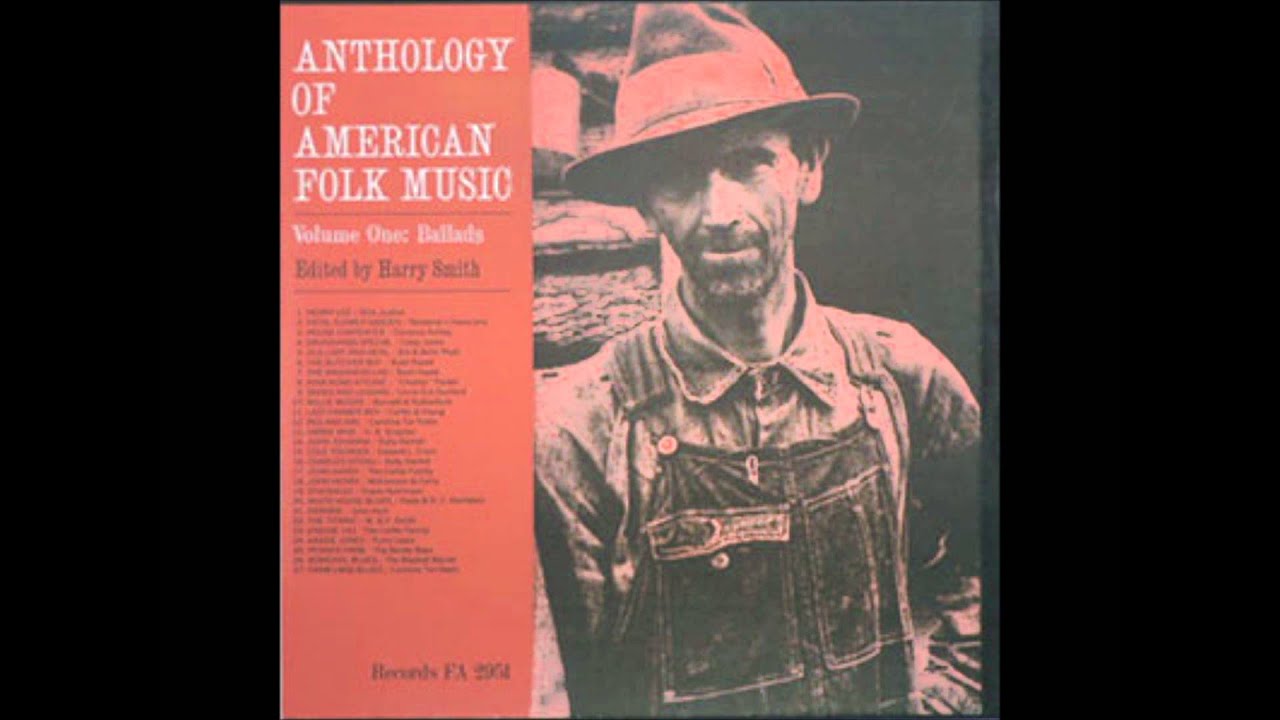

The Anthology of American Folk Music

(Folkways Records, 1952)

Aged 18 I worked in a Borders bookshop in a large retail park in Stockport off the M60. Somehow, in a way I can’t trace back, I went deep on Mississippi Delta Blues. My first full time paycheck went on a turntable and the one copy of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music that had been collecting dust in the glass display cabinet since I started – the terrible 6xCD edition that looks like a bootleg. To an 18-year old girl in Stockport this object was godly, mystical. It promised answers, was a recurring reference in everything I was consuming, but once I owned it I found I didn’t understand it. Facts were obscured by Smith’s esoteric framing: collage and alchemy, mystery and magic. This only heightened its place in my mind as an oracle into the depths of American folk music. Even the dates it covered were pretty arbitrary: 1927 to 1932 from some imagined beginning of recording technology to the Depression. I only liked half of it then, so much of it was so unfamiliar, but I have grown with it and grown into it, into Buell Kazee, the Carter Family, Clarence Ashley and Sister Mary Nelson’s judgement call.

Jennifer Allan

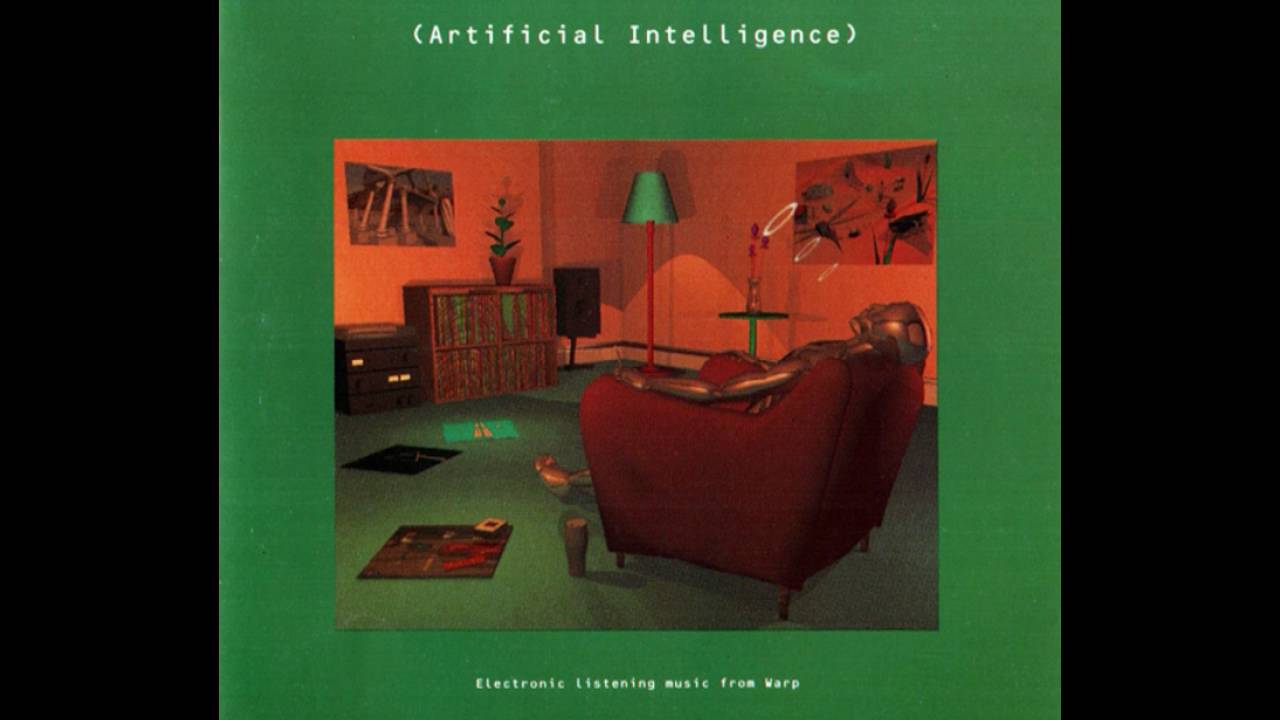

Artificial Intelligence Volumes 1 and 2

(Warp Records, 1992)

The Artificial Intelligence series on Warp took ambient music to a completely new dimension over the course of eight albums, released between 1992 and 1994. The sleeve image from the original AI compilation that kicked it all off featured a robot sat in an armchair blowing smoke rings with headphones on, and the album’s subtitle, ‘Electronic Listening Music From Warp’, gave a crystal-clear image of where the label felt this album would be best enjoyed. This was post-rave music made more for the mind than the body (or “techno untethered from the dancefloor,” according to Joe Muggs, writing in The Wire in 2013). The compilation laid down the blueprint for ambient techno, and was remarkable for showcasing the early works of a group of artists who would go on to define electronic music for years to come – Autechre, Black Dog Productions, Aphex Twin (as Polygon Window), B12, Speedy J, Richie Hawtin (as F.U.S.E.) and many others. The six artists mentioned also released albums as part of the series, all of which are incredible.

Joe Clay

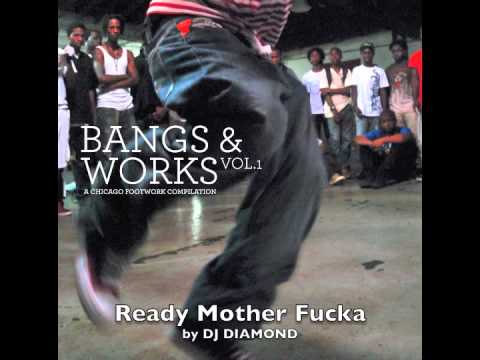

Bangs & Works Vol. 1

(Planet Mu, 2010)

Chicago footwork was, at the point this was released, basically an unknown quantity to everyone who wasn’t (a) living in Chicago or (b) a way-too-online Dissensus messageboard poster type. So if I speak of how raw, radical, revolutionary and category-shunning Bangs & Works sounded in 2010, that oughtn’t be overly presumptous. What’s wild is that it still sounds like that. An evolutionary step on from Chi-house, ghetto house and juke (in that order) but with a big whack of (then) modern rap influence in its drum programming, Planet Mu’s Mike Paradinas assembles relatively veteran footwork heads like DJ Rashad and RP Boo alongside no-fucks-giving teenagers like DJ Nate and DJ Yung Tellem.

A lot of these 25 tracks, marriages of frantically intricate breakbeats and swiftly recognisable samples, sail blithely between inspired and absurd, the apogee reached with RP Boo’s ‘Eraser’: an eternally brilliant agglomeration of doomy, dancefloor-unfriendly electronic drone, dude’s own chopped-up vocal and a Wings sample. Pour one out for Rashad (who died in 2014) and then take a moment to wonder why nearly half the producers on this disappeared from view pretty much instantly.

Noel Gardner

Brown Acid: The First Trip

(RidingEasy Records)

For my sins, I was ignorant of the cult reputation the Brown Acid series boasts when I first picked up its ‘first trip’ a couple of years ago; it was the brief three paragraphs of notes on the back that drew me in, telling a brief tale of the disillusioned youth for whom Vietnam and Altamont had shattered the flower power dream; “Expand your mind, embrace the bad trip, and follow us down a two-lane highway into the abyss that is the American Rock’n’Roll Underground…” it read.

This, the first volume in an ongoing series, would compile the ultra-rare 45rpm pressings by a host of killer amateur outfits, sold originally in tiny quantities outside shows and now worth hundreds on their own. It is wilfully primitive music, cluttered and clattering with a fierce stomp, played on cheap instruments and recorded on a tight budget. Musically there’s nothing all that deep, but so potent is the raw power of Brown Acid that as the series approaches its sixth volume that the world it explores remains completely transfixing.

Patrick Clarke

Cease & Desist DIY (Cult Classics From The Post-Punk Era 1978-82)

(Optimo Music, 2015)

“What all these tracks have in common is a certain attitude and an unwillingness to play by any rules,” writes J D Twitch in the sleeve notes to this Optimo Music compilation from 2015. “It was easy, it was cheap – go and do it,” read the subheading of an LP that captured not only the DIY spirit of the times but also the wild diversity, where everything from dub, funk, jazz, synth pop to krautrock, were all thrown into the post punk pot.

In Rip It Up and Start Again Simon Reynolds suggested “in terms of its broader cultural influence, it’s arguable that punk had its most provocative repercussions long after its supposed demise.” And you might ponder on this as you listen to the bedsit brilliance of Thomas Leer’s ‘Private Plane’ and discover the delights of long forgotten groups like The Spunky Onions. Apart from a couple of releases on Rough Trade (The Prats’ ‘Disco Pop’) and Y Records (Tesco Bombers’ ‘Break The Ice At Parties’) all the tracks come from obscure DIY labels up and down the UK. And as with all great compilations this one will have you searching for more obscurities on labels like East London’s Small Wonder and Glasgow’s Oblique Records.

Andy Thomas

Choubi Choubi! Folk And Pop Songs From Iraq

(Sublime Frequencies, 2005)

Created from Iraqi cassettes and LPs found across the world, Choubi! Choubi! is a statement – a catalogue of the extraordinary music produced under Sadam Hussein’s regime. Some of the most interesting tracks on the compilation come from Ja’afar Hassan, not only due to their uniquely Iraqi folk-rock but, because of their ties to the Iraqi Socialist Movement operating before Hussein’s rise to power. Hassan was the musical voice of said socialist movement, something rarely heard about in the West. Perhaps what is most notable here however, is the eclectic mix of instrumentation and rhythms present in each track. From employing scales disparate to those of the West, to the use of rapid machine-gun rhythms created by the Krishba (Arabic for wasp) hand drum.

Choubi! Choubi! is innately political, in its liner notes stating, “What has happened to Iraq since the 2003 US invasion and eventual occupation? Endless death, destruction and chaos, the complete take-down of a functional sovereign secular government [regardless of your opinion on that government], puppet installations, contrived sectarian divisions, the wholesale looting of culture, rampant opportunism, and apparently no lessons learned – all at the Iraqi people’s expense.” It’s intended to be provocative, music made in Iraq now is targeted and silenced, and this compilation is a reminder of the beautiful music that was made before it became near impossible to do so.

Alex Weston-Noond

Disco Not Disco

(Strut, 2000)

Whilst the innovations and implications of post punk, new wave and no wave have been discussed at length, it’s often overlooked just how many phenomenal pop songs that era spawned. From the ready-for-the-floor vibrations of Delta 5 and Liquid Liquid, to the phantom grooves of James Chance and Ian Dury & the Seven Seas, Disco Not Disco compiles the bastardised disco tunes that convulsed into being between 1974 and 1986. Whilst this compilation, across three volumes, slaloms between genres like a downhill snowboarder, every track is united by the fact it’s both strange and danceable.

Particular highlights come in the form of ‘Los Ninos Del Parque’ by EBM oddballs Liasons Dangereuses, a disco remix of The Contortions eternal no wave paragon ‘Contort Yourself’ and the 12" edit of ‘My Spine Is The Bassline’ by paleological industrial eccentrics Shriekback. This union of the obscure and obvious, the deep cuts and remixes, that blend so seamlessly into one another makes for the perfect compilation for those that always did more than just sit still when Can or Arthur Russell were playing on the radio.

Cal Cashin

The Golden Apples Of The Sun

(Bastet, 2004)

‘Freak folk’ was a label that many of its most lauded practitioners vehemently refused. And with good reason – the term suggested a certain ‘outsider’ status that most of the music did not warrant, while, as is often the case, the act of labelling in this way blunted much of the movement’s energy and excitement. So by, say, 2007, when Devendra Banhart’s Smokey Rolls Down Thunder Canyon, came out, this so-called genre had had its day, inevitably commodified and somewhat prone to gimmickry. Which is partly why this beautiful 2004 compilation is one to treasure.

Compiled by Banhart for the late, lamented Arthur magazine, The Golden Apples presents a number of artists within this community as fresh-faced greenhorns on their first album. Joanna Newsom’s ‘Bridges and Balloons’ is here, as is Vetiver’s ecstatically gorgeous ‘Angel’s Share’. Other acts to go on to moderate fame include Iron & Wine and Espers (whose ‘Byss and Abyss’ is 2000s freak folk in a nutshell). Of the artists who remained largely unmolested by their scene going mainstream, Jana Hunter (later of Lower Dens) stands out with ‘Farm, GA’, as do Troll with ‘Mexicana’ and the perennially underrated Currituck Co. with ‘The Tropics of Cancer’. The Golden Apples represents the apogee of this imperfectly classified style.

Barnaby Smith

Grime 2

(Rephlex, 2004)

Rephlex’s 2004 compilation Grime 2 didn’t actually take in much of the music associated with the MC-led sound of the genre from which it got its name. And rather than take in contributions from the sizeable number of excellent producers emerging during dubstep’s early days, the label instead, as with the first volume, chose to zone in on three of the genre’s biggest names. In tracks by Kode9, Loefah and Digital Mystikz though, the compilation perfectly captures one of the most exciting sub-genres to emerge from the UK in the noughties at its early stages. Put together by Rephlex’s co-founder Grant Wilson-Claridge after discovering the sound through pirate radio, Wilson-Claridge says he avoided using the term ‘dubstep’ when naming the record because it made him cringe.

Kode9’s contributions focus on stripped-back percussion and hard-hitting sub bass, while Loefah’s three tracks centre around warped vocal samples and stepping riddims. Digital Mystikz’ contributions meanwhile centre on the dread-filled darker elements of the 140 sound as it emerged from the dark garage that came before it. As with all of the best music from the era, these tracks are designed to be played out on weighty soundsystems.

Christian Eede

Hip Hop Don’t Stop, Volumes 1 & 2

(Solid State, 1997)

Anyone who’s ever assembled a genre compilation can tell you that compromise is always at the heart of it: what you can and can’t licence, what publishers and labels want to push or withhold. Which is why it such a rarity when a comp functions straight out of the trap as an all but definitive primer. Solid State records did an extraordinary job with their first selection of Old Skool hip hop, whose 27 tracks include such celebrated founding documents as Sugarhill Gang’s ‘Rappers Delight’ (1979) and Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five’s ‘The Message’, then cherry-pick stone classics and brilliant semi-obscurities across the range into the early 90s. It was justly greeted with (pun sort of intended) rapture, leading swiftly to a follow-up of equal variety, quality and relevance. If there’s a quibble, it’s the under-representation of female artists (who were, in fairness, under-represented in hip hop in general, as in many other genres.) But between the two volumes, you get an unsurpassable guide to hip hop’s first golden era.

David Bennun

Hyperdub: Next Life

(Hyperdub, 2014)

With footwork, arguably Chicago’s most hyperkinetic dance music export, suddenly receiving international attention in the wake of DJ Rashad’s triumphant 2013 Double Cup LP and, tragically, his untimely death a year later, the release of Next Life in late 2014 served several purposes; firstly, to raise money for Rashad’s family and celebrate the impact his legacy had had on the city’s electronic music scene, but also to demonstrate to the world at large that footwork had significantly more than one visionary DJ amongst its ranks.

Indeed, Rashad himself only appears once here, and even that’s a collaborative effort with peers Spinn, Taso and Manny. Next Life spends the rest of its 75 minute run-time highlighting the genre’s flexibility and diversity, ranging from lusher, breezier, more accessible cuts like DJ Paypal’s glossy, hip-hop influenced ‘FM Blast’ or Tripletrain’s atmospheric, The Wire sampling ‘Never Could Be Pt.2’ to harsher, aggressively repetitive material like DJ Earl’s ‘Wurkinn Da Bass’ and genre pioneer RP Boo’s punishingly minimal ‘That’s It 4 Lil Ma’, sparse tracks that bore into the listener’s brain like a pneumatic drill into a satsuma. Taken as a whole, Next Life flows remarkably well as an album, bristling with an intense, hyperactive energy and, as its title suggests, proving there is still life after Rashad for the genre.

Kez Whelan

In Order To Dance 5

(R&S, 1994)

It’s difficult to choose a favourite from R&S’ In Order To Dance compilation series having captured some of the 1990s’ finest techno producers at their peak across each volume. The fifth volume stands as a particular highlight however taking in contributions from the likes of Kenny Larkin, Luke Slater and Richie Hawtin under his Plastikman alias. Carl Craig’s ambient techno stunner ‘At Les’ crops up alongside Aphex Twin’s breakbeat-indebted ‘Polynomial-C’ (originally of course lifted from Richard D. James’ Xylem Tube EP for R & S), and another all-time ‘90s techno classic in the form of the glorious dub techno strands contained with Basic Channel’s ‘Phylyps Trak’.

The tracklist for the fifth volume of In Order To Dance chiefly covers all the bases of techno that were worth covering upon its release in 1994, placing some of the most eminent names from Europe at the time alongside some of the scene’s Detroit originators and in turn providing one of the best introductions to the genre that a newcomer could hope to come across.

Christian Eede

Jazz Satellites Volume One: Electrification

(Virgin, 1996)

On this 1996 entry in the Virgin Ambient series, Kevin Martin traces the electrification of jazz and its echoes through post-punk, industrial, post-rock, techno, and hip-hop. Two celestial bodies loom large in Martin’s cosmos: Sun Ra, and Electric Miles, or more specifically producer Teo Macero, whose innovations launched a million satellites. Macero’s 1963 ‘Equals’ is the earliest track here, its reverb and delay soaked orchestrations anticipating his studio sorcery with Miles Davis.

Rather than draw on the better-known Bitches Brew, Martin opts for 1972’s ‘Rated X’, where the Dark Magus blasts death-ray organ over Al Foster’s outrageous proto-junglist grooves. Any number of Ra tunes would fit here, but the eerie 1971 version of ‘Satellites Are Spinning’ is an inspired choice, with June Tyson’s commanding vocals and Ra’s clavinet calling out across the void. Martin’s selections illustrate the impact of synths, FX, overdubs and tape-edits on the outer limits of fusion (Herbie Hancock, Joe Henderson, Tony Williams Lifetime) and the avant-garde (Ornette Coleman, Roland Kirk, Alice Coltrane), and show how these Afrofuturist sonic fictions (to use Kodwo Eshun’s term) reverberate through the likes of Divine Styler, 23 Skidoo and Bedouin Ascent.

Stewart Smith

Kenya Special Volume 2 – Selected East African Recordings From The 1970s & 80s

(Soundway, 2016)

On Kenya Special Volume 2, the superb Soundway Records not only followed up the revelatory record that was 2013’s first edition, but at the very least equalled it and arguably surpassed its predecessor. What really stands out about both records is their diversity, the way compilers Soundway have not just ploughed a single furrow, but have formed a record that embodies and explores the nuances, nooks and crannies of what was a massively diverse scene. The Orchestre Conga Internationale provide muscular, potent jazz, while The Lulus band bring sunshiny, joyous pop. There’s low, dark grooves and there’s explosions of frantic energy, blissed out slow jams and spikey jabs. It’s sprawling, multi-faceted and completely excellent.

Patrick Clarke

Kitsuné Maison Compilation Two

(Kitsuné Maison, 2006)

Kitsuné Maison cultivated the stylish end of the effervescent ‘Bloghouse’ spectrum through the mid 2000s, pushing out grooves that swung between nu-rave, fashion-flecked electro, and fizzing indie rock. The French imprint asserted itself with eclectic but masterfully curated rides – a particularly mind-melting and path-beating release was 2006’s second compilation. Compilation Two recruits the label’s bigger names alongside fresh, off-kilter additions: the Knife collaborator Jenny Wilson provides twinkly Swedish pop and Digitalism dominates with a sinister cosmic stomper, while the Cazals lead the charge for English townie boys indie.

The thread that binds them all is a forward-facing psyche and oddball urgency, a rag-tag, aesthetic-driven, self-made genre. The unrelenting pixelated waves of Adam Sky’s ‘Ape-X’ would be a confident pay-off in a Bicep set today, and the grinding Martian Assault remix of Digitalism’s ‘Jupiter Room’ paces itself like it was made in the last few years. Nevertheless, the Boys Noize edit of Bloc Party’s ‘Banquet’ and MSTRKRFT’s take on Wolfmother pack a gloriously nostalgic sucker punch on a more recent listen. It’s a one-way ticket back to Skins-themed parties and neon accessories, multiple belts looped through drainpipe jeans. Ultimately, it’s reflective of a fun, dynamic, ego-shedding music arc.

Anna Cafolla

Modern Dance

(K-Tel, 1981)

1981 was one of the greatest years in pop. It was a world where ‘O Superman was battling for a chart position against ‘The Birdie Song’ and people like Julio Iglesias – who seemed positively ancient back then, but was actually ten years younger than you are now. Chuck in Shaky, Adam & The Ants, the birth of Brit Funk and – Christ – no end of medleys, and that was about the dimensions of it. Yet behind all this, there were a series of synth-prominent bands and tracks emerging, increasingly uselessly bracketed as ‘New Romantic’. By the end of the year K-Tel smelled a trend and rounded up some of the better tracks of the year – all chiefly synthesizer based – and latched on to the frilled coat-tails of the New Romantics with Modern Dance.

Looking back, the period when 1981 crossed into 1982 was a succession of fantastic moments: ‘Don’t You Want Me’ as the Christmas No.1; the 30 seconds of musique concrete opening ‘Maid of Orleans’ a few positions lower; ‘Being Boiled’ and ‘The Model’ becoming chart toppers five years after release as if to right history’s wrongs. Modern Dance came along right at the centre of all that and felt like a coronation of the synthesists.

While there were tracks that I knew and owned such as Japan’s ‘Quiet Life’, Landscape’s ‘Einstein A GoGo’ and The Human League’s Dare album, most of them such as ‘Fade To Grey’, ‘Joan of Arc’ and ‘New Life’ were finally liberated from Top 40 rundown compilation tapes. But it also shone a light on new, future obsessions such as The Cure and – for a few years at least until they got the Irish pipes out – Simple Minds. Sure it looked ostensibly like a round-up of Virgin acts, and one could argue that it may benefit more with swapping one or two selections (I won’t miss The News) in favour of bunging ‘Chant No.1’, ‘Tainted Love’, ‘Vienna’ or ‘Planet Earth’ on to give it a more indispensable snapshot of that year’s flavour, however it achieved all the key aims of a genre-related compilation – firstly by confirming that you’re in the right place at the right time, and also giving you some previously unheard pointers as to where to continue. For a 12 year old it was fairly mindblowing.

Ian Wade

Monsters, Robots And Bug Men

(Virgin, 1996)

One of the bands on here used to have a website whose discography advised people not to buy this album, because it was released by Virgin and everything on it was already available on smaller labels. Which is all well and good, but, like, excuse me for not having £300 or so spare to go straight to the source. It’s pretty mad that a major released Monsters, Robots And Bug Men, mind: two brimming CDs of mid-90s post-rock before that term got codified and pinned on yer Explosions In The Sky type simps.

The biggest names are Mercury Rev, Godflesh – talk about your genre in flux! – and Stereolab, then there’s a herd of cats respected in drone/spacerock circles (Windy & Carl, Third Eye Foundation, Roy Montgomery) but hardly in the business of licensing to conglomerates otherwise. Deep cuts by forgotten souls include Ui, a rad techno/jazz/kraut melange probably best remembered for featuring rock critic and strip club enthusiast Sasha Frere-Jones; and Sabalon Glitz, whose ‘The Lonesome Death Of Elijah P Woods’ is incredibly beautiful loner folk and whose founder member Chris Holmes was a kind of post-rock socialite who lived across the street from Barack Obama when this was recorded.

Noel Gardner

Motown Chartbusters Volume 3 (Tamla Motown/EMI, 1969)

The twelve volumes of Motown Chartbusters, released between 1967 and 1982, offer a wonderfully eccentric guide to Hitsville USA, featuring familiar classics alongside lesser-known gems. Then there’s the packaging, which in its ‘70s pomp encompassed Roger Dean’s insectoid spaceship (Vol. 6), and a Led Zep III style rotatable picture wheel (Vol. 7). The first five volumes are impeccable, with the funk, psychedelia and Vietnam infused Vol. 5 a popular favourite. But Volume 3 is perfection.

Released in October 1969, the album’s reflective silver sleeve captures the space age optimism of the Apollo 11 moon landing three months prior. Although it has moments of social commentary (Diana Ross and The Supremes’ startlingly bleak ‘Love Child’) the focus is on dancing, romance and heartbreak. The album is blessed with three of Motown’s towering masterpieces – ‘Dancing In The Street’, ‘The Tracks of My Tears’ and ‘I Heard It Through The Grapevine’ – but what makes it particularly special is its serendipitous mix of contemporary hits and re-released classics. As Alan ‘Fluff’ Freeman enthuses in his liner notes, ‘you’ve gone and got yourself a pretty tremendous album!!!!’ Not arf.

Stewart Smith

Mountains Of Tongues: Musical Dialects Of The Caucasus

(LM Dupli-cation, 2013)

More than just an introduction to an obscure corner of folk music, I’m not too proud to admit that Mountains Of Tongues practically introduced me to the entire Caucasus region full stop. The miraculously rich culture of the region, situated between Turkey, Russia, and Iran, gives rise to dozens of languages and dialects, plus just as many unique musical practices and instruments. The non-profit Mountains Of Tongues project (formerly known as the ‘Sayat Nova Project’) seeks to document the region, and captured these recordings in between 2012 and 2013 – which in itself seems miraculous considering the raw, ancient sound of the songs. Some of the ten languages featured on the disc had reportedly somehow never been recorded before. The nineteen tracks include scraped strings, ritualistic drumming, a cappella singing, lonesome lute plucks, duck-like blown reed instruments, and plenty else.

It’s a windfall for anybody keen on anthropology or ethnomusicology, with sparks from a variety of cultures are discernible – Yiddish folk, Sufi ritual music, Russian balalaika dances, the list goes on – but the most alluring element of Mountains Of Tongues is the emotional gut punch of the singers, and the idiosyncratic virtuosity of the players. Elliptical string plucks seem to fall over themselves magically from the hands of a player during a ‘Chechen Balalaika Melody’, while the Anchiskhati Choir Trio from Georgia cry, yodel, and interleave complex melodic lines until they sound like a far larger group. Documenting an underappreciated cultural region, Mountains Of Tongues does so much that’s objectively ‘worthy’ – but capturing some inexplicable acoustic musical magic, still hidden out in the field in the 21st century, is its biggest achievement.

Tristan Bath

Music From The BBC Radiophonic Workshop

(Rephlex, 2003)

To my millenial teenage brain, the idea of listening to a compilation of short tracks culled from the BBC archives sounded frankly like school. This was electronic music for people who didn’t get electronic music. At least that’s what I thought . When I realised this compilation was released on Aphex Twin’s Rephlex label though, I had to rethink. If that guy thought this was cool enough to release, then maybe…

Bit-by-bit the pieces fell into place. ‘Blue Veils and Golden Sands’ by Delia Derbyshire sounds like an offcut from Selected Ambient Works Volume II. With a drum track and some added bass, John Baker’s child-like arpeggios on the Radio Nottingham theme tune could practically be an Aphex acid track. The breadth of the sounds and emotions the workshop manage to squeeze out of such pioneering techniques across Music From The BBC Radiophonic Workshop is pretty miraculous too. Delia Derbyshire’s version of Bach’s ‘Air on the G String’ is particularly beautiful, seamlessly blending primal bleeps with vibraphones, while Malcolm Clarke’s comic ‘Bath Time’ is utterly absurd though no less groundbreaking. Music From The BBC Radiophonic Workshop didn’t only introduce me to the self-contained genre of the workshop, but it rewrote the history of electronic music for me.

Tristan Bath

Mutazione: Italian Electronic & New Wave Underground 1980-1988

(Strut, 2013)

Compiled by Alessio Natalizia, one half of Kompakt abstract duo Walls, this 2013 compilation from Strut focuses on the ‘80s electronic scene that spread across Italy in the aftermath of the political terrorism of the Years of Lead. Much of the DIY music was as dark, hostile and claustrophobic as the times, a point made by journalist Andrea Pomini (AKA electronic artist Repeater) in the extensive sleeve notes. Setting the tone is Die Form’s ‘Are You Before’ an abstract slab of paranoid jazz to unsettle the neighbours. Most of the recordings were made on cassette and promoted through band led fanzines. Take Suicide Dada, who emerged from a collective running the VM ‘zine in Turin, with the austere funk of ‘Waiting for September’.

Typical of the raw DIY sounds that emerged from these agitated bedroom producers, The Tapes (aka Giancarlo Drago) created ‘Nervous Breakdown’ by manipulating tape loops in his Genova bedroom. Similarly inspired as much by William Burroughs as Throbbing Gristle, the duo known as Plath from Prato captured the atmosphere that runs through this LP when they explained how ‘I am Strange Now’ expressed “the alienation, anxiety, loneliness and desperation of human beings in the selfish and classist ‘80s society.” But within this hostile environment, others would produce beautiful, melancholic pieces of electronic music like Victrola’s minor key masterpiece ‘Maritime Tatami’.

Andy Thomas

New Orleans Funk (New Orleans: The Original Sound Of Funk 1960-75)

(Soul Jazz Records, 2000)

The excellent Soul Jazz label, an imprint that grew out of the central London record shop Sounds of the Universe, already had a reputation for producing compilations that caught precisely the right balance between how hard-to-find a record was and the sonic wonderment it contained, but the first of their New Orleans Funk compilations, released in 2000, set a new high. The Crescent City’s take on funk was as singular and innovative as one might have expected from the birthplace of jazz, yet many of the greatest NO funk tracks were pressed on locally distributed 45s and achieved little wider attention.

The track listing Stuart Baker compiled for this magnificent record places the relatively easy-to-find likes of The Meters’ ‘Handclapping Song’ and Eddie Bo’s polyrhythmic masterpiece ‘Hook ‘N’ Sling’ alongside Marilyn Barbarin’s screaming belter ‘Reborn’, which would set you back the thick end of £500 for the original 7", while any of Aaron Neville’s swaggering yet vulnerable ‘Hercules’, Chuck Carbo’s almost punk ‘Can I Be Your Squeeze’ or The Explosions’ enigmatic, brittle ‘Garden Of Four Trees’ would likely cost £100 or more. The booklet gives more than enough back story to allow a newcomer to situate this marvellous music in its wider context, and is thorough enough to even include a bibliography.

Angus Batey

New York Noise

(Soul Jazz Records, 2003)

The first edition of Soul Jazz’s 2003 compilation New York Noise saved me on indie dancefloors from a full drowning in Happy Mondays and Britpop. New York Noise called itself dance music, which to me at the time meant house and techno, and this is nothing of the sort. It pulls together a collection of funk-work that hangs together by virtue of it all being off-grid, or hard to square off. The loose groove of Lizzie Mercier Descloux isn’t the first thing I’d stick alongside the locked and repeated guitar phrases of Glenn Branca’s ‘Lesson No.1’, or the bendy post-punk disco of ESG, but they hang together. New York Noise opened up my teenage dancefloors to that which was not white, was not male, was not Britpop or the landfill that came after. It pulled in something more futuristic, walked with a strange swagger to an underground funk I hadn’t heard before; painted a Big Apple full of possibility and weirdos, of sounds waiting to be found.

Jennifer Allan

Nuggets: Original Artyfacts From The First Psychedelia Era 1965 – 1968

(Elektra, 1972)

Back in the days of analog technology, limited media outlets and youth cult tribalism, the output of generational sub-cultures would soon be forgotten by all but the most dedicated of followers as the Next Big Thing swept away all that went before it. Compiled by music journalist Lenny Kaye in 1972, the original double album shone a spotlight on the fecund era of rock & roll’s second wave that was already in danger of being forgotten.

For those of us who discovered Nuggets in the 80s via torchbearers such as The Cramps, Hoodoo Gurus and others garage fetishists of the time, the album taught us several things. Chief among these was that the do-it-yourself ethos punk rock had been done so much earlier, thus throwing the perception of the 60s as some kind of blissed out pot, patchouli & paisley paradise into something more historically nuanced.

It also displayed the ramifications of Keith Richards’ fuzz guitar on suburban American youth hungry to start their own revolution whilst highlighting why the Stones were such an irrelevance in the 80s. But most importantly, and as evidenced by cuts such The Seeds’ ‘Pushin’ Too Hard’, The 13th Floor Elevators’ ‘You’re Gonna Miss Me’ and The Remains’ ‘Don’t Look Back’ among many others, this was music to dance and seriously lose your shit to. Oh, and that with The Amboy Dukes’ ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’, Ted Nugent hadn’t always been such an utter bellend.

Julian Marszalek

Personal Space: Electronic Soul 1974-1984

(Numero Group, 2012)

This compilation of disparate but somehow connected electronic soul cuts is threaded together by spectral traces of desire – a desire for stardom that these artists never found, or for sex-as-escape as on the languorous funk chant of ‘Are You Ready to Come? (With Me)’ parts one and two by US Aries. But don’t confuse this for a carnal soundtrack. It is more a playful, prototypic scrapbook of genres that might have been, such as the cosmic-baseball-organ jam ‘Starship Comander Wooooo Wooooo’ by the artist of the same name, the squelching electro stomp of Jerry Green’s ‘I Finally Found the Love I Need’, or Jeff Phelps’s understated soul croon over a svelte drum track, ‘Super Lady’. Released in 2012 it could be described as a Nuggets for the chillwave generation (some of these artists were championed by Sun Araw and Night Jewel at the time), but it deserves to be more than a faddish document. Rather, it is testament to the power and versatility of soul music. Is it too late for volume two?

Tim Burrows

Retro Techno: Detroit Definitive

(Network Records, 1991)

Compilations, usually, aren’t aimed at the purist. The experts and collectors will already know the music, and even if the act of curation helps highlight different aspects of a sound, style or genre, the benefits of that will be limited if you’re already an initiate. Yet if a compilation is to attain sufficient respect to convince newcomers that it’s telling a credible story, it cannot forget about the die-hard fans and their likely verdict on its contents.

Retro Techno: Detroit Definitive is an object lesson, and a truly high-level example of the compilers’ art. It brings together early, hard-to-find, but pivotally important tracks by the "holy trinity" of Detroit techno – Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson (one of the 12 tracks, Separate Minds’ ‘First Bass’, wasn’t produced by one of them, but Saunderson edited it) – and presents them in a way that makes this brutally minimal music understandable and relatable. To have done so without dumbing the music down, or causing cries of "sell out", remains remarkable. Kudos to Network Records A&R Neil Rushton for the decision to present the music simply and plainly, and to John McCready for the concise, precise sleeve note, while the track-by-track written contributions from Atkins, May and Saunderson are as taut and to the point as the music.

Angus Batey

Sorrow Come Pass Me Around: A Survey Of Rural Black Religious Music

(Advent, 1975)

I have neither the expertise or the inclination to make comment on Sorrow Come Pass Me Around being declared the greatest field recording anthology of gospel music in some quarters but it is an extremely fine record nonetheless. First issued in 1975 (you can get a typically luxurious Dust To Digital reissue from five years ago if you fancy owning it with a fancy pants booklet) it was mainly recorded by ethnomusicologist David Evans, with some help from other notables such as Ur-hipster John Fahey and Cheryl Thurber between 1965 and 1973, across the southern states of America. The songs benefit, I think, from being recorded by Evans’ request, mainly in domestic settings rather than during actual religious services. They gain an intense intimacy, given that most are just the unaccompanied voice or voices with guitars or banjos. There’s just as much pleasure to be had in standards such as ‘Glory Glory Hallelujah’ and ‘When The Circle Be Unbroken’ as there is in relatively obscure material like ‘The Ship Is At The Landing’ and ‘Can’t No Grave Hold My Body Down’. Essential stuff.

John Doran

Sounds Of Sisso

(Nyege Nyege Tapes, 2017)

The label Nyge Nyge Tapes have built up a rather faultless roster in recent times, releasing work from Africa and elsewhere by the likes of Otim Alpha and Riddlore – an artist who seamlessly intwines field recordings with bass-heavy floor fillers. Yet the release which has garnered the most ecstatic coverage is undoubtedly the Sounds of Sisso compilation, a record which documents the startling and abrasive Singeli sound, originating from the city of Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania.

The production on these tracks may be lo-fi but the execution is wholly maximalist, densely packed with rapid-fire, pitch-shifted vocals, and flows which consistently land on the track in any manner bar the way which seems most logical. This bustling sound is situated against caustically satirical lyrics, with topics such as police corruption and the dilemma of trying to date when you’re broke. In a climate of endless reissues – replete with bios that insist a lost classic has just been unearthed – it becomes all the more important for contemporary underground music to be supported in its own time; as far as forward thinking dance music goes, Sounds of Sisso is unequivocally vital.

Eden Tizard

Speed Kills II: The Mayhem Continues

(Under One Flag, 1986)

Until I was 16 I thought all heavy metal was pathetic, sexist trash for losers with inch-thick glasses who fantasised about slaying dragons. My friend Jon Hoare, later of the band Mercury Rain, put me right by playing me Metallica’s Master Of Puppets album and also this amazing, bargain-bin compilation. I can’t pretend it’s all gold, because there’s a couple of slightly dull, everymetal tracks on there, but so much of it hits bullseye that it’s little wonder it helped to turn me into a zit-laden thrash metal disciple. Helloween’s ‘Ride The Sky’ is, to this day, the only power metal song I can say I really love; usually the stuff is so polished and jaunty that it makes me gag, but this song was just melodic enough to be catchy while also being mesmerisingly fast.

The closing song, ‘Gung-Ho’ by Anthrax, beggars belief, with its insanely fast kick drums and rhythm guitar. Then there’s Onslaught, who were about as good as British thrash metal ever got in the face of the effortlessly superior equivalent from across the pond; the Canadian band Razor, whose aggression levels were quite shocking if you lived in rural Somerset, like I did; and of course Bathory, devil-worshippers from Sweden. It says a lot about the necro nature of Bathory’s music that, when my record player stylus clogged up with dust from the surface of Jon’s never-cleaned LP, I assumed the resulting lack of clarity was an intentional part of the music.

Joel McIver

Sub Base For Your Face

(Suburban Base, 1992)

It’s always exciting to hear music at the point of transition and to be able to isolate the exact moment when a genre transforms itself into something fresh, exciting and new. In 1992, breakbeat and hardcore music began evolving into jungle, which in turn mutated into drum & bass. The label at the forefront of this evolution was Romford’s Suburban Base. The label itself grew from the Boogie Times record shop, opened in 1989 by 18-year-old dance music obsessive Dan Donnelly. Suburban Base released its first 12” in April 1991, Kromozone’s ‘The Rush’, and had its first Top 40 hit with Sonz Of A Loop Da Loop Era’s timeless rave classic ‘Far Out’ the following year. The label would go on to have 12 Top 75 records, many of which are featured on the Sub Base For Your Face LP. The stand-out cut is the prototype jungle of the 2 Bad Mice remix of Phuture Assassin’s ‘Future Sound’, but most interesting is the novelty smash ‘Sesame’s Treet’ by Smart E’s. It reached number 2 during the height of rave mania – a staggering success for a label still being run by one person from a room above a record shop.

Joe Clay

Sushi 3003: A Spectacular Collection Of Japanese Clubpop

(Bungalow Records, 1996)

Back in 1996, significant effort was still required to unearth the underground sounds of far-flung countries like Japan, making the release of Sushi 3003 seem uncommonly exotic. Adding to its surreal nature, this so-called Spectacular Collection Of Japanese Clubpop was compiled in Germany by two Berlin based DJs, Holger Beier and Marcus Liesenfeld aka Le Hammond Inferno. The founders of Bungalow Records, their goal was to take the 1990s easy listening revival to the dancefloor, but the Japanese were already one step ahead of them, so Sushi 3003 (and its follow-up, Sushi 4004) documented their foraging trips to Tokyo’s Shibuya district. It was easy to bristle at the kitsch quotient of this Technicolor terror, with its ludicrous references to The Muppets, Ennio Morricone and Boots Randolph’s ‘Yakety Sax’, best known as Benny Hill’s Theme Tune. But it was also fascinating to discover the common ground shared by these magpie producers and crate-digging acts like Stereolab – whose ‘International Colouring Contest’ provided Les 5-4-3-2-1’s ‘Bond Street’ with its musical spine – even if they ended up in parallel dimensions.

Cornelius and Pizzicato Five were the most familiar names, but the latter’s perky ‘Nata Di Marzo’ – which could have been lifted from a screwball, 1970s comedy – was overshadowed by the downtempo, sitar-drenched grooves of SP 1200 Productions’ ‘My Super Lover’ and Kahimie Karie’s breathless ‘Good Morning World’, written by Momus. Calin With Fantastic Plastic Machine’s ‘Samba De Minha Namoradinho’, a day-glo universe of Bontempi organs and go-go dancers, took things to another extreme, and Hajime Tachibana’s ‘Moog Power’ presented Hugo Montenegro’s tune as if it were a Fatboy Slim remix. It all sounds preposterous now, of course, a short-lived aberration of taste worthy of scarlet blushes. At the time, however, it offered a gaudy reminder, only two weeks after Oasis’ Knebsworth shows, that music could be frivolous and fun, and that fabulous worlds existed beyond the reactionary borders imposed on popular culture by Britpop.

Wyndham Wallace

This Comp Kills Fascists, Volume 1

(Relapse, 2009)

Taking his cues from the Cry Now, Cry Later comps and Slap-A-Ham’s now-legendary Bllleeeeaaauuurrrrgghhh! releases, Agoraphobic Nosebleed guitarist Scott Hull curated a grindcore/powerviolence primer for the 21st century with This Comp Kills Fascists. Established names like Brutal Truth and Magrudergrind dished out all-new material alongside unsung ’90s powerviolence luminaries like Agents Of Satan and relative newcomers like Spoonful Of Vicodin, Maruta and Weekend Nachos (who had just one album to their name at the time) to create a thrillingly vibrant blur of violent, high-octane noise.

With most of these bands managing to cram a good four or five songs into their allotted three minute slot, This Comp… is like binging on grind split 7”s without having to get up and flip records every few minutes, and paints a particularly vivid picture of the late 2000s fast hardcore scene, with the Relapse backing undoubtedly helping many of these DIY acts to reach a much larger audience (as Agents Of Satan’s hilarious rapped intro will attest). Ten years after its release, it’s still an exhilarating listen and its crude, scattershot political commentary (lest we forget, the disc artwork featured a series of penises protruding from George Bush’s facial orifices to form a swastika) seems more relevant now than it did upon release.

Kez Whelan

This Is Kologo Power!

(Makkum/Red Wig/Sahel Sounds, 2016)

The kologo is a musical instrument found across west Africa, made with two strings and a stretched goatskin. It’s also a style of music which leans on slogan-y, call-and-response vocals, frantic – almost skiffle-like – strumming and, in some iterations, hip hop-influenced beats. Not on this compilation of nine kologo musicians from Ghana, though: King Ayisoba, one of the best known and most brilliant artists in the scene, was keen that This Is Kologo Power! highlight the raw-dog brass tacks of the sound, and compiler Arnold de Boer, Makkum label head and member of The Ex, obliged.

It’s front-to-back cracking, some of the most thrilling music being made anywhere: sometimes achieving funkiness with a gizmo whose component parts should render that impossible (Atambila, ‘I Have Something To Say’), often defiantly pro-African (Ayisoba’s ‘Africa’; Atamina’s bilious ‘Ghana Problem (Mind Your Own)’), invariably cranked out with such shitkicking crudity you can virtually hear the finger callouses forming. Despite my antipathy towards the practise of ascribing ‘punk’ values to people who don’t give a shit about punk, I wish to make an exception for Prince Buju’s ‘Afashee’, which reminds me of nothing so much as Chain Gang’s serial killer thugrock classic ‘Son Of Sam’.

Noel Gardner

300% Dynamite

(Soul Jazz Records, 1999)

Soul Jazz have spent more than 20 years developing themselves into world-class compilation dons, via tightly focused collections which are (generally, arguably) hipsterish, in a record-nerd sense, without seeming to exploit passing winds of fashion. With this in mind, 300% Dynamite! seems weirdly random in hindsight, regaling us with nothing more specific than ‘absolutely blazing old tunes from Jamaica’. One of them, Althea & Donna’s ‘Uptown Top Ranking’, was a UK number one single; another, Lloyd Price’s calypso number ‘Coconut Woman’, has no reliable info on its age anywhere online. If I choose to believe a cocktail menu which lists it as 1953, this makes 32 years between it and Wayne Smith’s ‘Under Me Sleng Teng’, which changed Jamaican music forever. As did Prince Buster, Lee Perry, Augustus Pablo and Sister Nancy, all of whom are on here too (albeit only Nancy with her signature hit). And, see, I know all this now – but in 1999, prior to snagging this, was 300% clueless about everything herein, then instantly transfixed by what I heard. This comp won’t impress anyone possessing even the faintest affinity with reggae’s family tree, but it’s one of my two or three favourites ever.

Noel Gardner

Tokyo Flashback

(PSF Records, 1991)

Tokyo Flashback is the most important compilation you’ve never heard of. It comprises two volumes (dose yourself chronologically) of music from the best Japanese underground noise label that ever existed: PSF. It has recently been reissued by Black Editions, who licensed the PSF catalogue wholesale, inaugurating the label with this, a pick & mix of the heaviest and best Japanese psych from the early 90s. This is about heavy, dark and noisy psych, not jangly 1970s rock with a fetish for paisley. Thanks to a handful of British music journalists: Biba Kopf, Alan Cummings, David Keenan, this stuff reached UK shores, bringing the gift of Masoki Batoh’s Ghost, White Heaven, Fushitsusha and Keiji Haino, and the perfect mess of High Rise (who named the label – PSF stands for Psychedelic Speed Freaks and is the name of their first album). It is heavy and psychedelic, lush, raging, and totally sublime.

Jennifer Allan

Torque

(No U Turn, 1997)

D&B has, over the past two decades, been obsessed with visions of the future. Often these have taken the form of epic cinematic soundscapes dripping in menace (Dom and Roland, say) or razor sharp audio design that emphasises pin drop clarity and head twisting progression (Photek, by way of example). No U Turn Records, however, presented the scuzziest and bleakest clairvoyant optics out there: tracks like Trace and Nico’s ‘Squadron’ sound like dereliction on a cosmic scale, some hulking long abandoned outpost on the outreaches of the galaxy, clanking and churning as rusted steel rivets are sucked into eternal orbit.

Founded by Nico Sykes in 1993, No U Turn tracked the progress from jungle to drum & bass with an unrelentingly bleak aesthetic and, alongside Moving Shadow and (later) Virus, pioneered the style that came to be known as Tech Step. The majority of music put out by the label was made by a core of four producers: Nico, Ed Rush, Trace and Fierce and ‘Torque’ – released in 1997 – remains the last word in a style often imitated but never bettered. Nightmarish Reece bass, smashing amen edits and all manner of creepy bleeps and escape valve hisses are the audio hallmarks. It’s the absolute antithesis of ‘drop a minute’ modern day D&B – this is music about tension, the dynamic use of space and, above all else, creeping dread. But while modern producers fight for the cleanest mixdowns, No U Turn Records were always imbued with a crust of dirt, an imperfection and warmth that gave their mechanical nightmares a sense of human fallibility – the ghost in the machine.

Harry Sword

Trevor Jackson Presents Metal Dance

(Strut, 2012)

Compiled by musical gatekeeper and designer Trevor Jackson, Metal Dance is an expansive look into 1980s martial industrial-cum-disco. Featuring the well-known likes of, D.A.F., 23 Skidoo and SPK, Metal Dance is most rewarding when it comes to the unknown gems, Zazou Bikaye’s ‘Dju Ya Feza’ being a notable high point on the compilation. Everything here is drenched in Cold War paranoia, a definite sense that nothing was going to get better; The Berlin Wall would never fall, disasters like Chernobyl would become the norm and the advent of nuclear annihilation was just around the corner. Despite this, there are some surprisingly forward-thinking tracks which range from the prophetic, proto-acid house ‘Voices’ by Neon, to the downright wacky ‘The Bubblemen Are Coming’ by (you guessed it) The Bubblemen.

The standout track here is the compilation’s namesake – which may be surprising. For those who were around when SPK went ‘mainstream’, ‘Metal Dance’ was cited as the antithesis of industrial. This was largely a reaction to the three-minute album version, however what we see on Metal Dance is the original, seven minute version – an absurd, leathery disco track complete with moans of pleasure and inane lyrics about working in a factory. Classic.

Alex Weston-Noond

Universal Sounds of America

(Soul Jazz Records, 1995)

Back in the summer of 1995, I worked in an independent record shop. And an album was released that we couldn’t play in the shop without selling 10-15 copies. And it wasn’t Oasis or Blur or The Three EP’s by The Beta Band. It was Soul Jazz’s Universal Sounds Of America compilation. The rush to the counter usually started around song two – I still regard Art Ensemble of Chicago’s ‘Theme de Yoyo’ as essentially the best song of all time and certainly, the most visceral distillation of pure joy ever captured on tape.

But the best compilations don’t just work in the here and now. They sustain you for years. Back then, it was simply the soundtrack to a long, hot, happy summer. But 23 years on, I’m still processing USoA. I’m still wandering down pathways that exposure to David Durrah and Sun Ra and Pharoah Sanders opened up. Would I have got here without USoA? Maybe. But the route wouldn’t have been so scenic. For the indie kid I was, this compilation was a pivotal musical moment; a moment when my third eye was well and truly wiped clean and I understood what I really needed.

Philip Harrison

Venezuela 70: Cosmic Visions Of A Latin American Earth

(Soul Jazz Records, 2016)

There has almost certainly been much written about the power of Soul Jazz elsewhere in this article; and for good reason. Such was their reputation as undisputed kings of the comp, and so supreme were the reggae compilations I’d buy at random as and when they arrived at the local record shop in my then-native Liverpool, that when I moved to London their Soho base of operations, the Sounds Of The Universe record shop, became a point of pilgrimage.

I decided to pick a record about something I knew literally nothing about, safe in the knowledge that the label would see me right, and chanced upon this striking collection of Venezuelan experimental rock bands in the 70s, a period when the South American nation was arguably the continent’s cultural powerhouse, where musicians to this day barely known beyond their borders were combining Western forays into experimental electronics with Latin and Afro-Carribean polyrhythms, with healthy doses of funk, jazz and prog. To me, deliberately uninitiated, it felt like the best genre compilations should, as if I was being guided by a true and caring expert.

Patrick Clarke

The Very Best Of Éthiopiques: Hypnotic Grooves From The Legendary Series

(Buda Musique, 2007)

Genre compilations tend to have one of two purposes: either to offer you a grounding in/selection of something with which you already have a passing familiarity; or to introduce you to something altogether new to you. It’s a reasonable bet that if you’ve heard Ethiopian popular music from the 1960s/70s, French label Buda Musique had something to do with it. By the time Buda released this 28-track set, its Éthiopiques series was ten years old and 30 volumes in: a quantity and diversity only an ardent enthusiast could have kept up with. This distillation from that series leans heavily towards the jazzy/funky end, often from gigging acts who played hotel bars and suchlike, and includes only a handful of more traditional numbers. Non-tonal music will always sound exotic to the tonally inclined Western ear, and the influence of modal jazz is evident on much of The Very Best Of Éthiopiques. Yet nothing here is void of the wonderful, peculiar quality that imbues music from a culture with a history and set of sources quite unlike any other.

David Bennun