In the 70s, as many African nations were working to define themselves beyond the weight of colonial oppression, a country in the heart of the continent was crafting its own revolution – not just politically, but sonically too. Zambia, newly independent, landlocked, and learning to stand on its own, gave birth to a music that cracked the air like lightning.

Zamrock wasn’t just music, it was rebellion; a sonic renaissance and a radical act of self-definition, funneled through fuzz pedals, sweat, and spirit. Drawing from psychedelic rock, garage funk, blues, and traditional Zambian rhythms, it was raw and unpredictable – like James Brown jamming with Black Sabbath in a Lusaka backyard. The distortion was heavy, the grooves deep, the energy untamed. A generation stood at the fault line between past and future and claimed it as central. What they created wasn’t an echo, but an origin point. The world is only now beginning to catch the frequency.

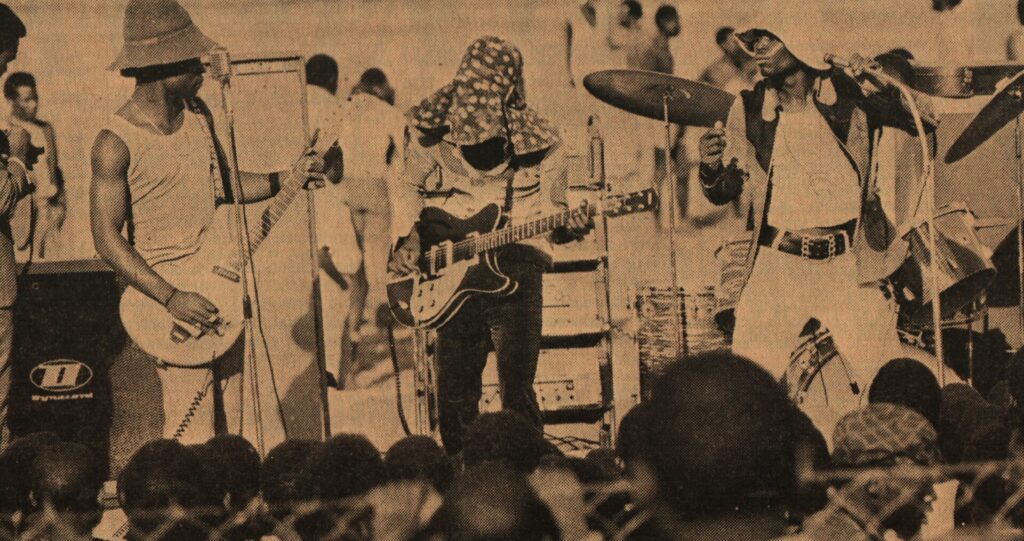

Who better to cast that first spell than W.I.T.C.H., an acronym for We Intend To Cause Havoc? This was not just a name, but a manifesto. They didn’t knock politely; they kicked the door in. Draped in floppy hats, bell bottoms, and sending out raw distortion, they pressed Zambia’s first commercial record with their debut album Introduction, and turned every stage into a portal. They weren’t just a band but a cultural glitch: stylish, subversive, and loud enough to wake the neighbours. The band are back in 2025 with new album Zango and European tour dates this autumn.

But WITCH was just the beginning. There was Rikki Ililonga, often called the godfather of Zamrock, whose lyrics struck like ancestral memory. His band, Musi-O-Tunya (meaning The Smoke That Thunders, the original name of the mighty Victoria Falls), carried the same weight of thunder and healing. The Ngozi Family, led by Paul Ngozi and powered by drummer Chrissy Zebby Tembo, gave working-class Zambia its soundtrack: raw, bluesy, and full of fire. Amanaz, with their now-cult album Africa, delivered slow-burning grooves brimming with beauty and weariness. And Salty Dog offered existential honesty that now feels prophetic, even though they were overlooked in their time.

Zamrock artists blended Bemba, Nyanja, and Tonga with English, creating a sound as local as it was cosmic. It wasn’t just cross-cultural. It was cross-dimensional.

This wasn’t happening in a vacuum. Zambia’s first president Kenneth Kaunda was a musician himself who championed local culture, mandating that 90% of music on national radio be Zambian. That single policy became fuel and suddenly, bands had airtime, an audience, and a reason to push boundaries.

A striking feature of the era (something my mother remembers vividly, even though she was young at the time) was how every band member, not just the frontman, was seen as a star. Whether you played drums, bass, or rhythm guitar, you had fans. You mattered. That kind of egalitarian spotlight is rare in music history, but in Zamrock, it felt natural. Maybe this is because the music itself was communal, born from jam sessions, village shows, and shared struggle, especially in the Copperbelt area that relied on mining. Many musicians were miners or the children of miners and their music reflected that: unpolished, united, powerful.

For people like my parents, and for those of us digging through dusty vinyl stacks, Zamrock is more than nostalgia. It’s an inheritance; proof that we’ve always had something to say loudly, beautifully, on our own terms.

The echo still rings. You hear it in Tyler, The Creator’s ‘Noid’, which samples Ngozi Family’s ‘Nizakupanga Ngozi’; in Travis Scott’s ‘Siren…