Until I first held a copy of The Underworld Of The East in the British Library sometime in the late 90s, I had my doubts about its existence. I knew it only from an extract in a collection of drug writings from a New York underground press (The Drug User: Documents 1840-1960, Blast Books, 1991) where it was included alongside the usual suspects – Charles Baudelaire, Henri Michaux, Anaïs Nin, Aldous Huxley – and introduced by a short and scabrous rant against the War On Drugs by William Burroughs. Though the extract was presented as the memoir of a British mining engineer in the South Asian colonies in the 1890s and 1900s, it read suspiciously like a modern pastiche. As various aficionados of the genre had pointed out, its plain and amateurish prose was quite unlike the better-known examples of fin-de-siècle drug literature; its progressive social attitudes towards non-Europeans, as well as its gung-ho frankness about drug-taking, seemed incongruously modern; and it was odd that nothing seemed to be known about Lee in real life. Some observed knowingly that "Lee" was the maiden name of Burroughs’s mother, and his nom de plume for the first edition of Junky in 1953.

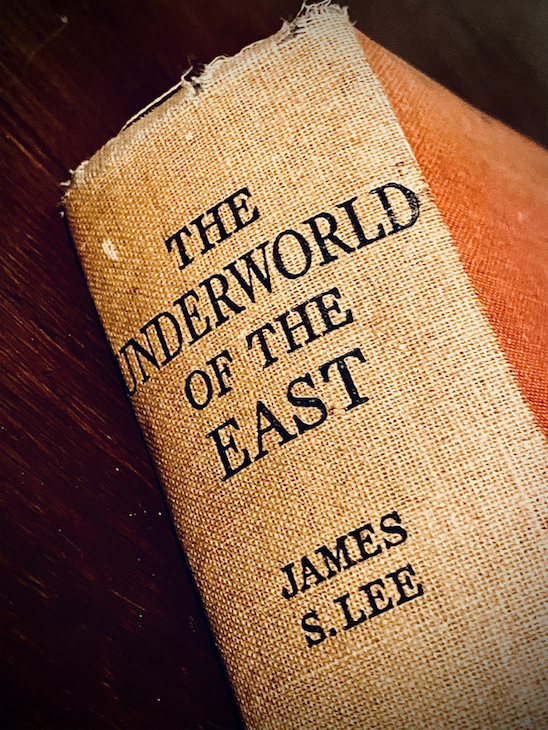

Any suspicion that it was a modern forgery was convincingly rebutted by the frayed and faded cloth jacket and yellowed, foxed pages of the British Library’s copy. When I opened the covers, James Lee had me at the title page: The Underworld Of The East: Being Eighteen Years’ Actual Experiences Of The Underworlds, Drug Haunts And Jungles of India, China And The Malay Archipelago. It was dated 1935, 20 years after the end of the episodes it related, and was essentially a travel memoir, offering some of the armchair thrills expected by readers of the genre: a village in the Indian jungle stalked by a man-eating tiger; close encounters with murderous Thugs and dacoits; adventures on one of the first motorcycles in Calcutta in 1903. But its distinctive theme, most unusual for its strait-laced times, was Lee’s voracious drug experimentation. "A man deeply learned in every kind of narcotic drugs… among them being opium, hashish, morphia, cocaine, bhang, ganja and many others," the dust-jacket blurb announced, "For 18 years he travelled the world investigating the drug habit and the underworld… the strange effects produced are intimately described."

In the book’s short opening chapter, ‘About Drugs’, Lee sets out his stall: "The life of a drug taker can be a happy one; far surpassing any other, or it can be one of suffering and misery; it depends on the user’s knowledge." I had recently been commissioned to edit an anthology of drug literature and had been working my way through reams of flowery, decadent 19th-century prose without ever coming across this obvious statement of fact. The doyen of the genre, Thomas De Quincey, had famously insisted that the pleasures of drugs were inseparable from their exquisite pains; his great admirer and translator Baudelaire declared that drugs were a "forbidden game" in which base instincts for self-gratification would always triumph over noble ambitions of self-transcendence. Publishers embraced this trope, which allowed them to sell immorality while absolving them of the charge of promoting it, and De Quincey and Baudelaire’s legion of successors and imitators were happy to encourage the conceit that the ecstatic pleasures they described were only accessible to the elite few who were equally prepared to plumb the depths of hell.

By Lee’s time, these tropes had hardened into the clichés that still define the tabloid "My Drug Hell" narrative: what goes up must come down; anybody who thinks they have their habit under control is deceiving themselves; drugs are a one-way street to perdition. But Lee, from the opening pages of his book, was having none of it – perhaps because he simply wasn’t aware of the narrative. He was born in Redcar to a family of colliers and iron merchants and employed in factories from the age of 17; his writing makes no reference to the canon of drug literature, or indeed any literature. His style is precise but artless: short, factual sentences, eccentrically punctuated, the work of someone more used to turning out structural engineering reports. His turn of mind is restlessly practical: the proper use of drugs is a problem to be solved. Their pleasures can, with careful attention to doses and combinations, be wonderfully intensified; their pains, with knowledge and self-discipline, can be more or less eliminat…