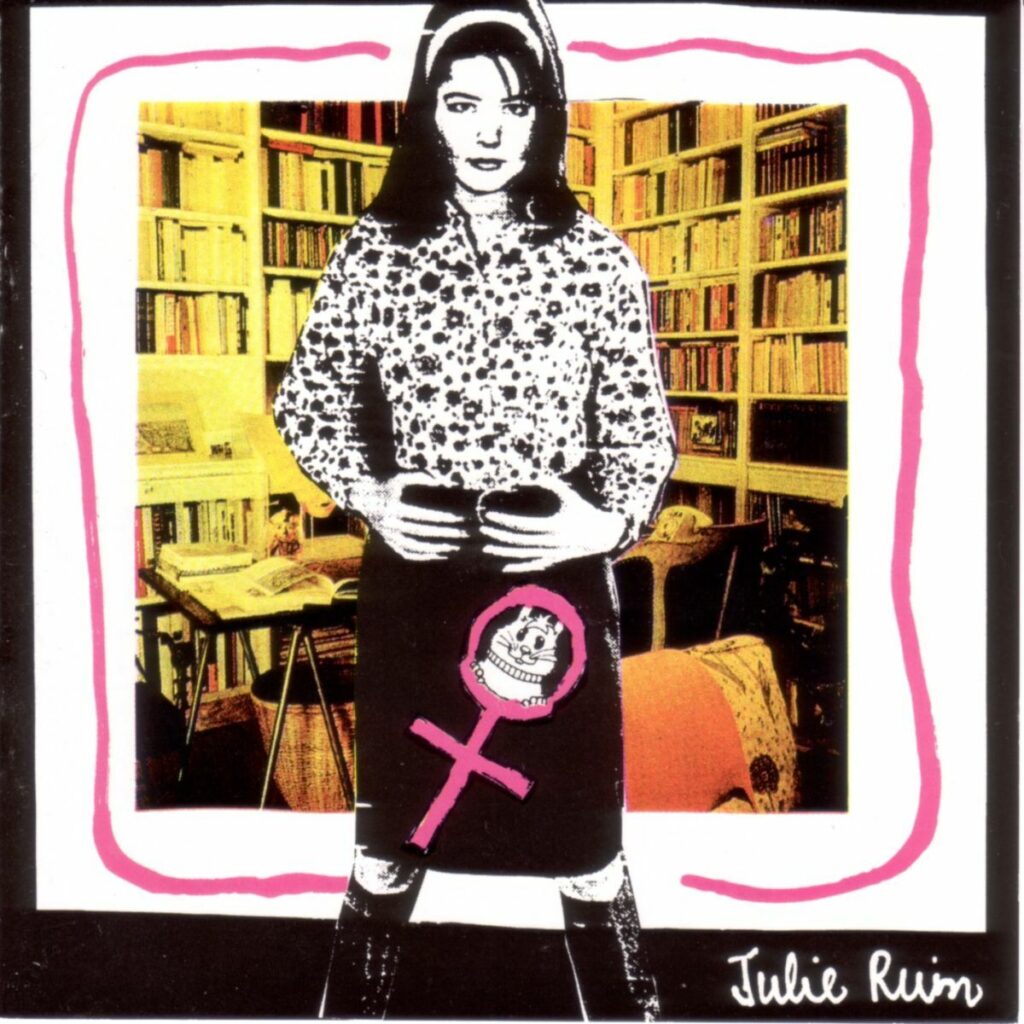

For about a decade my iTunes library could compete with some of the most eclectic music collections out there. You want one off singles from long forgotten noughties electroclash kids? I’ve got it. Maybe a rare radio session of a 90s alt rock star downloaded from a little read blog in the middle of the night? I’m your girl. How about a compilation of South African Mbaqanga girl groups? You’re covered. I had everything, but I was also lazy and once streaming services became normalised, I transferred my vast library to an external hard drive to free up space on my laptop and let it collect pixelated dust. My iTunes library’s residence on my external hard drive means I have to remember to plug it in and then reload whatever song or album I want to listen to on my Apple Music app. I rarely go about this time-consuming process, but on one recent perusal I rediscovered an old favourite, the album released in 1998 under the moniker Julie Ruin by riot grrrl veteran and Bikini Kill frontwoman Kathleen Hanna.

If you’ve never heard it before, Julie Ruin is a masterpiece that defines Hanna as a creative visionary. Written and released as the sun went down on the iconic feminist punk riot grrrl era of the early 90s, Julie Ruin is Hanna’s first and only solo album, recorded entirely in her Olympia, WA, bedroom. The album was far removed from her political punk background in Bikini Kill and saw Hanna experiment with lo-fi electronic bedroom pop, a glitchy $40 drum machine, looped vocal samples, and hyper distorted renditions of soothing poetic verses. Julie Ruin sounded like the past and the future all at the same time; a lo-fi art pop creation that documented female expression in the late 90s and solidified Hanna’s legacy as a pivotal feminist artist.My love for this album is one of the many reasons I can never fully get on board with trusting my entire music library to streaming. Despite its importance to many fully grown elder riot grrrls and punks out there, Julie Ruin is out of print and unavailable on any streaming services or music download sites. Beyond a few kindly YouTube users who uploaded the whole album a few years ago, the record mostly exists on the old hard drives and in the imaginations of elder punks like me, and risks being forgotten.

With no physical copy to hold in my hands, on some days I question whether Julie Ruin ever existed. Occasionally a snippet of the cut and paste, DIY electro pop songs would interrupt my thoughts in the middle of the day. Did I imagine those words? Is this the soundtrack to a life I didn’t know I lived? Then it came back to me; these are Hanna’s words. Words that she conjured as a way of writing a new future for herself. To understand why this record is so important to the punk landscape and also within Hanna’s discography we need to understand where Hanna was in her life at that moment and why she needed to write the album in the first place.

When Hanna started working on the Julie Ruin project in 1997, her life was at a crossroads. Her band Bikini Kill had released their final album Reject All American the year prior and, although there had been no announcements, the band were struggling to communicate and would eventually break up in 1998. Hanna was living in Olympia, a hotbed of riot grrrl activity at the time.

As the frontwoman for one of the scene’s most prominent bands, Hanna was seen as a leader, but she began to back away from the role, unsure how to deal with the movement’s race problems and the bad faith actors who used riot grrrl to work through their own personal issues. What’s more, her small amount of fame left her feeling disconnected. She was subject of constant critique and attention from both the riot grrrl scene (some members of which saw her as a bad feminist) and the mainstream media (who accused her of not being a real musician).

Hanna was at a place in her life where she was struggling to def…