Before you read on, we have a favour to ask of you. If you enjoy this feature and are currently OK for money, can you consider sparing us the price of a pint or a couple of cups of fancy coffee. A rise in donations is the only way tQ will survive the current pandemic. Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours.

I’m almost ashamed of not having come to Lucio Battisti’s glorious Anima Latina (1974) before the lockdown, since in a way it had been right under my nose the whole time; I grew up with Battisti’s music. Born in Rome, my mum had been a teen pop obsessive – a package she received in 1966 from the Official Italian Beatles Fan Club was addressed to ‘Beatle-person N 643’ – and Anglophile, to the extent that she eventually married a long-haired English man and moved to the UK.

At home and in the car, together with the Beatles and various international acts she liked – Abba, The Bee Gees, Billy Joel – we listened to recent releases by Italian artists like Antonello Venditti, Claudio Baglioni and Battisti.

His first album after he had ceased working with lyricist Mogol – E Già, released in 1982 – was an excursion into moody electro pop that had me speculating about how its songs might all be made to fit the plot of a fantasy/sci-film, slotting in like Queen’s music did in Highlander.

‘Windsurf Windsurf’, a song literally about one of Battisti’s hobbies, could be employed for a scene introducing us to the free-living hero.

For a while in my early teens – and in my ignorance – I found the whole notion of Italian pop embarrassing, just hugely uncool. Maybe it was also too much a part of the furniture. A little older, I spent a few months staying with an aunt and uncle in Rome, and my aunt would sing one of Battisti’s late-60s classics, ‘Non È Francesca’, while she was pottering around the flat, to the point that I had to ask her who it was by.

Intrigued again, I found it on a compilation in my parents’ collection and promptly added it to my latest mix tape. Several years after that, during a very brief spell working in Milan, I bought (and played to death) neat little ten-track CDs in a series on BMG-Ricordi called ‘I Miti Musica’ (‘the musical legends’) devoted to Mina – another giant in the history of 20th-century Italian pop, and preeminent interpreter of Battisti songs – and Battisti himself.

The last, and latest, track it featured, the radiant ‘La Collina Dei Ciliegi’, was from 1973. Later still, after my mum’s death, I found 1977’s Io Tu Noi Tutti in her collection, an album from the period which saw Battisti take a Bee Gees-like turn, heading to the US to follow his passion for the latest funk and disco sounds.

As far as I was concerned, nothing of much consequence had happened between ‘La Collina Dei Ciliegi’ and the hypnotically languid ‘Amarsi Un Po’. The Light In The Attic reissue of Amore E Non Amore from 1971 only compounded this mistaken belief. It was described as “his own Histoire De Melody Nelson”, a concept album divided between ‘love’ songs – heart-tugging instrumentals with gorgeous string arrangements and unwieldy titles like ‘7 Agosto Di Pomeriggio Fra Le Lamiere Roventi Di Un Cimitero Di Automobili Solo Io, Silenzioso Eppure Straordinariamente Vivo’, a track to perhaps be filed alongside Milton Nascimento and Lô Borges’‘Clube Da Esquina, No 2’ – and rockier ‘non-love’ songs.

Of these, the lusty ‘Dio Mio No’ and ‘Supermarket’ (in which the percussive sound of the English-language title locks in perfectly with the scratchy guitar) are highlights, while rocker ‘Se La Mia Pelle Vuoi” rattles along enjoyably but is hardly essential. This, I reasoned, must have been as far out as Battisti had gone; nothing more to see. I’ve rarely been happier to discover that I was wrong.

There are a couple of lines by David Bowie about Lucio Battisti that you can find floating around online. One comes from Gianfranco Salvatore’s book L’Arcobaleno – “My favourite singer by a long way is Lucio Battisti.” And in 1997 he apparently declared that Lou Reed and Lucio Battisti were his two favourite singers and that he would have loved to collaborate with the latter (Battisti died the following year). This looks as if it was to coincide with a trip to Italy to promote the Earthling album and its single ‘Little Wonder’ so it is of course possible that Bowie was flattering his Italian audience to a degree.

But Bowie had already collaborated with Battisti, in a manner of speaking. During his Roman holiday with Mick Ronson in 1973 following the recording of Pin Ups in France, they spent time in a “beautiful house with a beautiful pool” (according to critic Renzo Stefanel) on the outskirts of the city, hanging out with movers and shakers in the Italian industry and soaking up the music. One of the songs they heard repeatedly, Battisti’s soaring ‘Io Vorrei… Non Vorrei… Ma Se Vuoi’ from Il Mio Canto Libero (the country’s best-selling album that year), made it on to Ronson’s debut solo album Slaughter On 10th Avenue as ‘Music Is Lethal’ with lyrics credited to Bowie – and eventually also to Ronson’s girlfriend (and Ziggy’s hairstylist) Suzie Fussey.

And it’s not difficult to imagine Bowie feeling some affinity with Battisti, a multi-instrumentalist, perfectionist in the studio, composer of unusually structured songs and someone always looking for new directions and stylistic hybrids to explore.

Battisti, born in 1943 in the small hillside town of Poggio Bustone in northern Lazio before moving to Rome, had started out playing in bands there, in Naples and with Milanese group I Campioni. Spotted by Christine Leroux of the Ricordi label, he was paired up with Giulio Rapetti aka Mogol to write songs for other artists, including popular beat (or bitt) groups like Dik Dik.

Mogol was not only one of the most sought-after lyricists of his generation but also a facilitator with influential connections – his father, Mariano, was general manager of Ricordi’s publishing division for many years. The two would be close-to inseparable for long periods, living together or as next-door neighbours. As a songwriting duo, they scored 26 Top 20 hits including some that Battisti would go on to record himself, like beat/psych band Equipe 84’s ’29 Settembre’ and ‘Nel Cuore, Nell’Anima’. ‘Il Paradiso’ was a hit for Patty Pravo in 1969 after Amen Corner had already covered it as ‘(If Paradise Is) Half as Nice’.

Once Mogol had convinced Battisti to step forward as an artist in his own right, success soon followed in the shape of b-side ‘Balla Linda’ (covered by Californian band Grass Roots as ‘Bella Linda’). The song is one of several early successes like ‘Acqua Azzurra, Acqua Chiara’ which demonstrate Battisti and Mogul’s knack for rousing choruses, making the most of the mouth-stretching Italian open ‘a’ sound.

Even when it came to his earliest hits, Battisti was already an unconventional songwriter who drew on Italian canzonetta, ‘beat’, R&B, baroque psychedelia, blues rock and more as it suited his purposes. Sometimes it’s not so much a question of synthesis as employing more than one style in the same song, with abrupt changes illustrating shifting perspectives.

‘Mi Ritorni In Mente’ switches between an elegiac sort-of chorus devoted to an idealised image of the loved other, and more frantic sections which accompany the intrusion of more unwelcome memories. Battisti and Mogol’s innovations frequently went hand in hand. In Made In Italy: Studies In Popular Music, Jacopo Conti describes how the striking, chorus-free ‘Le Tre Verità’ (‘The Three Truths’) is “a description of a betrayal inspired by Akira Kurosawa’s Rashōmon, in which he (Battisti) plays the vocal roles of the woman (high voice) the betrayed man (middle-high) and the discovered lover man (middle).”

In spite of his melodic brilliance, versatility and penchant for formal experimentation, Battisti wasn’t to everyone’s tastes. He emerged as complex and heated discussions were taking place about the purpose and content of songs that would see even Umberto Eco weighing in. The 60s had brought a dramatic break with the operatic ballads and jaunty Tin Pan Alley-inspired numbers that dominated the hugely influential Sanremo festival (or Festival della Canzone Italiana di Sanremo).

A sea-change occurred with the arrival of Domenico Modugno, who wrote and sang ‘Nel Blu Dipinto Di Blu’ – better known around the world as ‘Volare’. He used dialect and sang in a “husky, nasal and forced vocal style… far removed from both bel canto and the crooners’ style,” according to Roberto Agostini in Made In Italy – a description one could easily apply to Battisti’s singing as well. It was the dawn of the urlatori and urlatrici, the ‘yellers’ or ‘shouters’ – the new sound for rock & roll-inspired, freedom-seeking teens.

But immediately some started demanding more from their popular music than commercial, US-influenced frivolities, like the Cantachronache group founded in Turin in 1958, with members including Eco and Italo Calvino. They campaigned for greater ‘realism’ and, increasingly, political engagement in songs.

Several of the Cantachronache members published the Adorno-inspired Le Canzoni Della Cattiva Coscienza (‘Songs of Bad Conscience’) in 1964, with a more nuanced preface by Umberto Eco who felt that the themes of “entertainment, escapism, fun, relief” in what he called canzone diversa were not to be dismissed out of hand. But ethnomusicologist Roberto Leydi declared in 1965 that although the nouva canzone being called for should be “the expression of an objective reality in all its contradictions”, the reality expressed should be “the reality of workers’ situation within the neo-capitalist system.”

The stakes were raised dramatically by the suicide in 1967 of Luigi Tenco, described by Sociologist Marco Santoro as a “cultural trauma”. It clearly had an impact on my mum since she told me the story when I was still quite young. Tenco was one of the first wave of Italian singer-songwriters – cantautori, a contraction of the words for ‘singer’ (cantante) and ‘writer/auteur’ (autore) – also signed to Ricordi. Unlike Battisti, though, Tenco wrote both music and lyrics and was actively engaged in bringing greater social realism into Italian song. In this TV performance he very deliberately signals that he’s doing away with artifice and light entertainment staging – through what is itself clever mise-en-scene, making a song and dance about not making a song and dance – to get to the essence of “the words, just the words” and a song which is “real, accurate, modern.”

Tenco’s suicide (he was found with a bullet in his left temple, and his death still inspires fevered debate and conspiracy theories – look at the link posted with the above video to “five pieces of evidence that Luigi Tenco was murdered”) occurred after ‘Ciao Amore, Ciao’, a song about emigration, didn’t make the cut for the final of the Sanremo festival that year. He called it his “gesture of dissent” against an Italian public that hadn’t understood his music or his aims. For the Italian left he was a martyr. Poet, novelist and Nobel Prize-winner Salvatore Quasimodo wrote in the Il Tempo newspaper that “Tenco wanted to strike a bloody blow to the mental sleep of the average Italian.”

Mogol had ventured into ‘protest’ territory with lyrics for a song called ‘La Rivoluzione’, presented at Sanremo the same year and sung by Gianni Pettinati and Gene Pitney. With its vague gestures towards “a better world” and love winning out, it was kept in the competition at the expense of ‘Ciao Amore, Ciao’ and Tenco called it out explicitly in his parting message.

Battisti demonstrated little obvious interest in politics and his songs are most often concerned with matters of the heart (and the flesh), employing themes and language considered hackneyed by musical neorealists and post-68 radicals (who also in some cases accused him of having links with the far right) despite the fact that they could encompass reflections on memory and its unreliability, self-deception or, as in the pair’s most emblematic composition ‘Emozioni’, the impossibility of truly knowing others or ourselves: “Something that is within me but doesn’t exist in your mind, you just can’t understand, you can call them, if you like, emotions.”

As the cantautore, which as with auteur theory in cinema revived the essentially Romantic notion of the lone genius, become ever more central to Italian popular music’s image of itself, Battisti was felt by some to be unworthy of the term since he didn’t write everything himself (with the song-as-text elevated above imaginative arrangements, structures, sounds, performance, feel). Accusations of misogyny in Mogol’s lyrics were far closer to the mark.

In the wake of his early triumphs as a solo artist Battisti, who had always had a strained relationship with the press, withdrew from live performance and promotional duties, preferring to let his recorded music do the talking. Fortunately, the Italian public were listening. Even the more challenging Amore E Non Amore was the 10th best-selling album in Italy in 1971. However, tensions with Ricordi over the release, with the label preferring to put out a compilation of singles, Emozioni, as Battisti’s second album, led to Amore E Non Amore coming out on the Numero Uno label which he’d set up with Mogol.

Subsequent releases combined hugely popular ballads like ‘Il Mio Canto Libero’, ‘E Penso A Te’ and intimate epic ‘I Giardini Di Marzo’ with canny rockers and genuinely exploratory pieces like ‘Il Fuoco’, with its freeform use of feedback, distortion and wordless wailing.

Though nothing in Battisti’s catalogue fully anticipates the sublime composure of Anima Latina, a little of its spirit stirs in immediate predecessor Il Nostro Caro Angelo, mixed by John Leckie. The 1973 release foregrounds some of Battisti’s most fluent rock guitar, but synthesisers are also more prevalent, and his interest in il rock progressivo apparent. There’s already a nod to Brazil on ‘Ma È Un Canto Brasiliero’ and Battisti was clearly in tune with efforts to revive and reinvigorate Italian folk music(s).

The album’s most unusual track ‘La Canzone Della Terra’ – which Ricardo Villalobos has apparently slipped into DJ sets – contains lyrics like “on waking up in the morning, when the cock forces my eyes open at four, first thing, sliced polenta.” It evokes ways of life still very much present in Italy at the time (and which have yet to disappear entirely), and which held a fascination for both Mogol and Battisti – in 1970 they had decided to travel the 300 miles from Milan to Rome on horseback, looking for “real contact with nature” and an escape from the pace of work and contemporary life.

Valerio Mattoli, in Superonda: Storia Segreta Della Musica Italian draws comparisons between ‘La Canzone Della Terra’ and progressive folk groups like Canzoniere del Lazio, with its ritualistic singing, polyrhythmic drumming, wobbling, clattering and insectoid electronic noises. Opener ‘La Collina Dei Ciliegi’ (‘The Hill Of Cherry Trees’), meanwhile, is a powerful exhortation to aim “higher… further.” Battisti was about to do just that.

In February 1974, Battisti and Mogol headed to Brazil and Argentina for a rare, 20-day promotional tour, with Battisti appearing on a Brazilian TV special intended to launch his Latin American career. Renzo Stefanel’s book Anima Latina provides a fastidious account of the period leading up to and including the recording of the album (literally producing the receipts to back up his assertions), and is at pains to demonstrate that the pair were almost certainly still in Brazil for that year’s carnival; the idea of their journey “culminating” in the carnival would appear to be a crucial element of the album’s mythology.

During the recording of Anima Latina, Battisti gave an interview to producer and journalist Renato Marengo that was considered “the scoop of the century” and in which he discussed the impact of the journey:

“My long stay in Brazil, and in South America generally, made me aware of another dimension to music: music as life, as a way of being together, dancing together, protesting together… when I came back to Italy I could no longer stand the manner in which music is understood and the role of singer in our society. I felt a need to be together with people, not above them.”

Another crucial trip in February, to London this time, resulted in the purchase of a white multi-effects unit that is generally referred to as the ‘bidet’ but which Stefanel identifies as a limited-edition (only 450 were produced) EMS Synthi Hi-Fli, also used at the time by prog giants Steve Hackett and Dave Gilmour. In the preceding years, prog rock had made a remarkable impact in Italy, with the likes of Van Der Graaf Generator having far more success there than in the UK. Battisti’s was more than a passing interest – he was producer and mentor to progressive (or “nuovo pop) band Formula Tre, who split in 74 and birthed supergroup Il Volo.

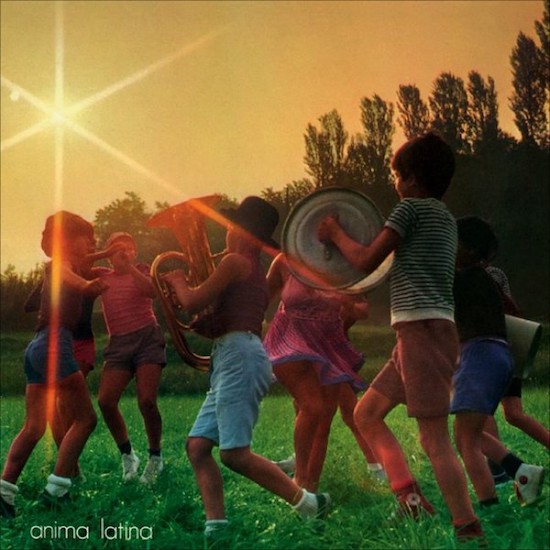

Anima Latina’s sleeve features photos taken by Cesare Montalbetti on the lawn outside the building where rehearsals for the album took place, the ‘mulino’ (mill) of Anzano del Parco in the northern Lombardy region. It was also there that Marengo had run into Battisti while scoping out the mill with Neapolitan drummer Tony Esposito. Although the actual recording took place at the Fono Roma studios, there are parallels with British groups like Traffic ‘getting it together in the country’, minus the hallucinogens; the mulino, a commune established by Mogol, was still in the process of being kitted out as a full studio (when rehearsals started the mixing desk hadn’t been properly installed), trout were abundant in the nearby lake and the musicians would eat home-cooked food, sitting round a table with a red and white-checked table cloth, osteria-style.

The photos feature children from the families of the various band members, invited to bring musical instruments or pots and pans for an open-air party, and actress Dina Castigliego as the ‘latin soul’ herself, captured in the golden sunlight.

The ‘soul’ (and this is soul meant in the sense of spirit or being – soul music in Italy is just il soul) that Battisti was trying to tap into on Anima Latina is nebulous and all-the-more seductive for it. In the Marengo interview he talks about feeling that British and American influences and commercial imperatives were leading to a loss by “us Mediterraneans” of “the creative spirit, the vitality that has always characterised us.” Latin American inspirations (including perhaps Tropicália) break through vividly on the title track, but elsewhere so do influences from Spanish music and of course the ‘Mediterranean’ melodies and harmonies of canzone and Italian folk.

Other sounds evidently on Battisti’s radar were the krautock of Tangerine Dream and Popol Vuh, and the symphonic soul, funk and fusion sounds emanating from the US. Mattioli considers it a “Balearic” album that “radiates that sensual, warm and dazed light which 15 years later would beguile young people experiencing the empathic delirium of ecstasy.” To me, it also recalls Gram Parson’s equally hazy, syncretic ideal of American sound – you might call it Cosmic Latin Music. It’s very explicitly cosmic in outlook at times – the word “universo” appears repeatedly and there’s a song called ‘Gli Uomini Celesti’ (‘the heavenly’, or ‘celestial men’). Either way, it’s clear that an ideal of shared experience, communion accessed through love and music, animates the record.

Summarised, the album’s narrative can look prosaic. Loosely, it’s the account of a relationship from the rush of initial attraction – the collision of ‘Due Mondi’, ‘two worlds’, resulting in re-enchantment and the return of childish innocence and freedom – to the foundering of this ‘free’ love in the face of inevitable possessiveness and the strictures of bourgeois coupledom. There are undoubtedly echoes of Mogol’s post-divorce personal life if you care to look for them, and 1974 was the year of the Italian referendum on the repeal of a law, passed a few years earlier, that had made divorce legal for the first time. The divorce laws remained in place, and there’s no real doubt about which side Mogol and Battisti were on.

But the lyrics on Anima Latina appear, more than on any other Battisti album up to that point, in a supporting role. I’ve seen opener ‘Abbracciala Abbracciali Abbraciati’ compared to Talk Talk and even The Flaming Lips (and it is kind of like something Wayne Coyne’s troupe have been groping at intermittently for the past 20 years) but – with its funereal pace, sparse drums and ghostly synth-flickers, Battisti mumbling before words start to form – the band it puts me in mind of most is The Blue Nile.

It’s the sound of someone emerging from emotional deep-freeze, still bruised (“What do you think, tell me, about a man stupid enough to think you were his?”) but ready to reach out again. Battisti’s voice is unusually low in the mix, a move that was beyond the pale in the context of canzone.

Unsurprisingly Mogol, as both artist and businessman, didn’t approve, but Battisti was keen to explore the voice as a texture – he called it the “strumento-voce”, “voice-instrument”. His hugely characterful but brittle, ragged-edged vocals are softened by reverb so that they mingle and almost melt into the brass, and he tends to stay in his upper register. His intention was also for people to listen more attentively. He explained to Marengo that “when you’re talking in a group of people, if your voice is of interest to someone listening then they pick you out… that’s what I’ve done with my album, I’ve put my voice within my music to encourage people to understand the words, to grasp the meaning or just the sound. Not because it’s pleasurable, but because listening means something… it’s the method I’ve chosen for communicating with others, to be present among people.”

Although the basic songs, including lyrics, seem to have been pretty much in place when the sessions at the mulino began (with Mogol sometimes making small changes on the fly), it’s in the studio, in the performances with some of the finest musicians available – including drummer Gianni Dall’Aglio, guitarist Massima Luca and bass player Bob Callero, who appears in the credits as Bob J. Wayne – and production, that the magic happened. Midway through, ‘Abbracciala Abbracciali Abbraciati’ shifts into a bustling, jazz-funk bridge replete with warm, gluey bass and very fluttery-sounding flutes and sax (they were recorded at half speed, and presumably sped up again) before returning to its stately initial tempo. The spectre of symphonic soul, some of the finest music in existence for elevating our tawdry romantic crises, also looms large, especially in the horn lines and the Isaac Hayes-like ending.

His music had never sounded this cavernous, with space opened up at least partly by the dipping of the vocal level, judicious use of hard panning and the absence of distorted electric guitars; they’re either acoustic or have been run through the bidet to achieve a shimmering, crystalline sound.

‘Due Mondi’ is the encounter with the ideal other, woman or ‘spirit’, given voice by singer Mara Cubedda. Battisti asks, “What do you want?” to which she replies, “Making love among the vines, the water falls but it doesn’t extinguish me, I want you.” It starts with a swampy, down-pitched throb and rises into an irresistibly frisky, horn-powered, samba-esque stomp. One stunning track succeeds another – ‘Anonimo’ starts in ballad mode, drifting in on a bed of squishy keyboards, Battisti’s voice swirling in the mix, before the laid-back groove kicks in and various, effected instrumental voices (synth, flute, glockenspiel; toys and pots and pans were also employed on the album) appear in turns. It breaks briefly into a spine-tingling and very Morricone-esque, arpeggiated two-chord sequence, flute and keys doubling each other, then a stream of ambient synth which, as well as previewing ‘Anima Latina’, guides the song to a stirring conclusion, delivered in a style that can only be described as electro-fandango.

Even with the multiple sections, everything flows, scenes bleeding into each other as in a dream until the abrupt kiss-off – an almost sarcastic, oompah-band citation of ‘Giardini di Marzo’, perhaps a sign of Battisti’s desire to ‘demythologise’ his image. ‘Gli Uomini Celesti’ is just as sumptuous, with its gently corkscrewing guitar lines, percussive breakdown that lingers on the corner for a few moments with Miles Davis, and grand, keyboard-soaked coda.

Short reprises of ‘Gli Uomini Celesti’ – in something approaching the Catalan rumba style later popularised by The Gipsy Kings – and ‘Due Mondi’ prepare the way for Anima Latina’s title track. The samba-like sway returns in the opening, instrumental two minutes before Mogol’s lyrics provide snapshots of life in Brazilian favelas, a few poor-but-happy clichés together with more trenchant observations about the influence exerted by US capitalism and consumerism (a sign reading “Drink Coca Cola”). But the glory is in the accelerating excitement of the music, climaxing in wordless and childlike chants, horns and stampeding percussion and bringing with it the sense of communal “revolt” (Battisti’s own word), of community as revolt. Step by step, it takes you from the position of an observer to the heart of the festivities and, in doing so, makes Mogol’s touristy vignettes work, as though they’re just a staging post in an evolution of consciousness.

The giddy, slippery ‘Il Salame’ (it’s a sausage joke, but also about rediscovered sexual innocence) goes through numerous twists and turns before we’re treated to the fleeting but imperious funk of ‘La Nouva America’. With its strident horns, almost aloof strut and slivers of guitar snaking around in the middle-distance, it takes its cue from Earth Wind & Fire but flashes forward to Young Americans and even Station To Station. It’s essentially an instrumental but it is perhaps intended to announce the intrusion of (US-style) acquisitiveness.

The album concludes with a brief, free-floating lament, Separazione Naturale – “Ah! If only I’d had time to love you a little more.” It’s the end of the affair, and of course Battisti the artist already had half an eye on other horizons. But the complex song that precedes it suggests something more: ‘Macchina Del Tempo’ means time machine, and lyrically it ends with the saudade-ful wish that “I would never lose anyone, and no-one would ever lose me”. Then in the outro we get miraculously superimposed sections edited from ‘Abbracciala Abbracciali Abbraciati’ and ‘Anima Latina’.

This kind of reprise wasn’t exactly an uncommon device in albums of the period but here, as well as giving a feeling of musical completeness, it seems to reflect a desire to relive not just the good times but even the melancholy moments preceding the transition to a new perspective. And thanks to the time machine that is the recording studio or the recorded artefact itself, it is possible to retrieve the experience over and over; this ‘soul’ can be revived at any time.

I’d argue that Anima Latina is really Battisti’s Histoire de Melody Nelson, although that does beg the question of what ‘a Melody Nelson’ is other than a marketing category. Is it from a particular era (specifically the early-to-mid 70s)? Does the artist have to be non-British/American? Is it a ‘concept’ album? A masterpiece by a major artist that was previously neglected in some way? Gainsbourg’s Histoire de Melody Nelson was critically well received in France but sold poorly.

In spite of Marengo’s enthusiasm, the overall critical reception in Italy to Anima Latina was generally either muted or uncomprehending, at best saluting Battisti for trying, but it sold relatively well even without a single (‘Due Mondi’ only made it as far as a pressing for jukeboxes). Released at the end of 1974 it sold 250,000 and topped the charts; it was only a flop by Battisti’s standards, and was easily outsold in 1975 by cantautore Francesco De Gregori and the soundtrack to Dario Argento’s Profondo Rosso, featuring Goblin.

Maybe ‘a Melody Nelson’ is an album that stands out as something singular, immaculately executed but sealed off, an island in an artists’ discography and a pointer in a direction that they never explored further (although Battisti’s late-period work in collaboration with poet Pasquale Panella has its charms). Perhaps it’s also a touchstone for later musicians and anyone ‘in the know’, its aura and influence increasingly asserting itself over time. Together with the Marengo interview, the album convinced many at the time that Battisti wasn’t a fascist after all, and brought about a rapprochement with the ‘underground’. But, as Nur Al Habash from Italia Music Export points out, many bought it simply bought it because it was by Battisti, maybe listened once or twice and then let it gather dust. It was then ripe for rediscovery in “your uncle’s record collection.” The process of critical rehabilitation in Italy over the last couple of decades means that it is now frequently cited in Italy as Battisti’s classic, with books, articles and podcasts devoted to it.

Naturally the internet has played a key role, and not only with regards to streaming (Battisti’s catalogue from 69 to 80 arrived on Spotify last year). According to Al Habash, Anima Latina’s sleeve, which already seems to have had a sepia-toned filter applied, was perfect for the “Instagram aesthetic”, and she recalls seeing many people sharing photos of it, or of themselves holding it. Numerous acts have also cited the album as a direct inspiration; Milanese pop-rap duo Come Cose went as far as releasing a song called ‘Anima Lattina’ in 2017 that sounds very Battisti-esque. The title translates as ‘tin can soul’, taking up Anima Latina’s anti-consumerist concerns. Other figures to openly celebrate its influence on their work include indie balladeer Andrea Laszlo De Simone and the wonderfully idiosyncratic, experimental songwriter Iosonouncane (aka Jacopo Incani).

“Your experience of having just discovered it while already being aware of Battisti’s music is kind of the story of this record,” he tells me. “It’s an album I’ve known since I was a teenager, I don’t remember how exactly but I got hold of a cassette that was a compilation of Battisti songs and it had ‘Anima Latina’ on it. So I heard this track and it kind of left me in shock, so from there I listened to the whole album. It’s always been under the radar as far as the general public is concerned. In Italy there’s very much a culture of celebrating famous people’s lives, especially after they’ve died, so Battisti is constantly being spoken about on TV, on an almost daily basis. But he’s talked about in terms of his most accessible and in a sense innocuous music, so Anima Latin and his late work are always kept out of the picture. For me it’s an important album as an artistic gesture, more than for its constituent parts. It isn’t a record by an unknown musician, Battisti was the musician in Italy, the Italian singer par excellence. And the beautiful thing is that he decides to tear up the song form and propose something that was utterly different from what he was famous for.”

Incani also has an idea about why Battisti never ventured further down the path opened up by Anima Latina. “In recent years I’ve read a lot of interviews he did where he spoke about it, and he considered it this almost isolated experiment rather than a first step. And it’s probably for that reason that he hit the accelerator and stripped away any kind of reference that his audience, who loved the songs with choruses you could sing along to at the top of your lungs, could identify with.”

In the UK and US, Lucio Battisti’s ‘progressive’ credentials have been long overlooked in favour of Goblin (darker and bound up with the cult of giallo) or Franco Battiato, one of the Italian artists featured in the Nurse With Wound list, and whose cheerleaders include Jim O’Rourke. But we could all do with letting an album this lush and expansive into our lives at the moment; Italy has gradually been waking up to the wonder of Battisti’s Anima Latina, and maybe it’s time for the rest of us to join in.