It’s 1999, and a school IT lesson deep in the south east London suburbs. Our teacher asked who had a “home PC,” and everyone except me raised their hands. I’d been late to the party before, when at the end of the 80s my family finally brought home a Sinclair ZX Spectrum, long after the underdog British home programming era had been overtaken by Japanese games consoles. This time I’d been outflanked by the affordable personal computer boom and a new wave of eccentrically British (and, it’d turn out, equally, doomed) manufacturers such as Time and Tiny PCs. The latter’s shop at a Bromley shopping centre squatted in a row of units intended for similarly boutique, high-end brands, yet the blue chip company would be insolvent within a year. The shop floor was directed by a Fagin figure, ringmaster to a group of reluctant local lads in polyester ties. Their exceptional south east London sales patter was unarguable, but their knowledge of computer science, perhaps not so strong. Eventually though they convinced Dad to cough up for the lot on finance: a full home PC suite with monitor, speakers, printer and the bespoke MDF desk to complete the control and command centre, and we were finally future-facing.

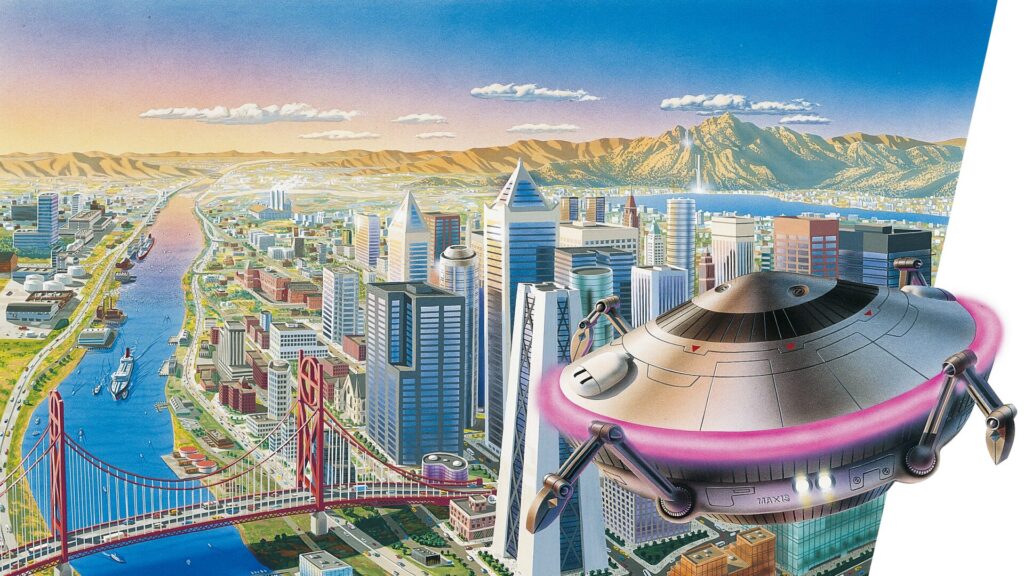

The family PC was a portal to the SimCity collection of computer games. Launched back in 1989, it was a pioneer of the ‘management simulator’, in which players founded and tried to run their own cities, micromanaging anything from town planning complaints and transport infrastructure, to ungovernable crime epidemics and Act of God natural disasters. Like millions of others, I later became obsessed with The Sims, the year 2000 spin-off that focussed in on the suburbs of SimCity and the lives and aspirations of its individuals and families; a semi-detached teenager managing his own scaled down suburbia, mucking up his own ‘miniature garden’, in the words of Super Mario designer Shigeru Miyamoto. It was the idea of limitlessness akin to a lucid dream that made The Sims so appealing, a sensation only heightened by the soundtrack that borrowed from anything from BossaNova to New Age. It balanced atomic attention to detail with leveraging the abundant imagination of the player, serving as a walled sandbox of escapism from the suburban reality. The game might have been inspired by designer Will Wright’s experience of trying to rebuild his home and life after the 1991 wildfires that wrought havoc in Oakland, California, but through it I found a way out of 90s Bromley, and the deafening boredom of the quiet English suburb.

In retrospect, The Sims, and its wider SimCity universe, is a particular cultural artefact from the end of the century. Like The Truman Show film from 1998, The Sims skewed the sunlit uplands of Western materialism with a hyper-aware satire of late 20th century suburbia. What both The Sims and The Truman Show played with were ideas of modelled living and a deeply embedded – and highly lucrative – fantasy of a world that revolves around the individual. Both needed deiform human tormentors, as did the contemporaneous TV franchise Big Brother, for which said tormentors were the voting members of the public. At the outset, the Dutch format still had aspirations of a studious sociological experiment offering an omnipotent experience for its viewers, before quickly giving way to a competition for finding new types of everyman celebrity, its contestants willingly handing themselves over for poking and prodding via a premium rate phone number. In The Truman Show