The late 1990s had seen a shift in what might be called ‘gay programming’, especially on Channel 4. There’d been the Red Light Zone, which started in 1995 and featured the likes of Robert Mapplethorpe and Tom of Finland documentary Daddy and the Muscle Academy which, well, let’s just say I’ve since replaced it on DVD. The news that the station had commissioned a ‘gay drama’ was seen as par for the course of its then boundary-pushing remit.

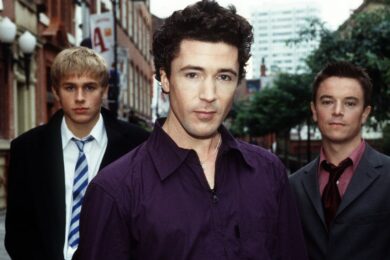

Queer As Folk, which was first broadcast on 23 February 1999, was based around a trio of main characters. You had long-time buddies, advertising executive Stuart (Aiden Gillen) and supermarket manager Vince (Craig Kelly), whose nights out and lives become disrupted with the arrival of teenage Nathan (Charlie Hunnam). The secondary characters were as fleshed out as the leads. There was Coronation Street stalwart Denise Black as Vince’s mum Hazel, future Corrie mainstay Antony Cotton as the camp-as-tits Alex, Jason Merrells as Phil Delaney, and – in what was seen as a bit of a move at the time – Neighbours star Peter O’Brien as Cameron, the man who Vince begins a relationship with. The ensemble helped were a ‘chosen family’, something familiar to many gay people who bond with friends who they feel comfortable with, a likeminded bunch who you’d get drunk/ stoned/ occasionally have sex with, but also pay bills, go to supermarkets, sit in front of TVs. These were lives lived against the backdrop of another star of the show, Canal Street, Manchester’s gay mecca where everything felt possible – Queer As Folk practically acted like a tourist guide.

Queer As Folk broke the expectation that a gay drama would be miserable – it wasn’t some gritty eurgh of rent boys, and shook off the clichés of closeted repression, hopeless stolen moments and death from AIDS. As important as the furtive gay breakthroughs made in soaps such as EastEnders and Brookside had been, there was always a feeling of disgust or ostracising in the post for the characters. Queer As Folk’s most shocking thing was to show just how bloody normal LGBTQ+ people actually were. It’s noteworthy that it was the first show to be produced for Red Productions by Nicola Shindler, who’d worked on Our Friends In The North and Cracker. It would propel the company into mainstream television, and they’d go on to work on award-hoovering northern-based character-driven dramas Clocking Off, Happy Valley and Last Tango In Halifax. That’s what Queer As Folk reflected: everyday people who just happened to be gay.

I’d not long been ‘out’ when Queer As Folk arrived. Indeed, I was in a first phase of outness with friends and colleagues – mainly anyone who wasn’t close family. There was no big announcement or notice in the papers and my closet was still very much in one piece. Up until a few years earlier I’d mentally tussled with what was going on as I sat on the fence, and had considered what percentage of gay I was on a spectrum – some days 70 per cent gay, other times at least 98. I at times thought I was hedging my bets in case the right girl I haven’t met yet finally decided to turn up before I officially pledged any allegiances. This was partly through fear of what might happen should I come clean, which might just explain the drinking and depressive tendencies.

It was only when I started working in London, making the weekly trip to do shifts at various publications, did any kind of acting on it transpired – damp towel manoeuvres in a sauna, a spot of knobtouch in a sex shop, hastily speed-drinking in certain bars, and so on. I was doing what any 90s regional homosexual would do when offered the adventures that London, or the Manchester depicted in Queer As Folk. After encountering one such fellow traveller on the train heading home to Suffolk, it turned out that I was hardly alone. A double life of light deceit and shooting ropes over strangers was not as rare as I’d thought. It had its moments, naturally, but the conflict would return the moment I walked back from the station. Queer As Folk, where everyone had come from somewhere else, felt utterly familiar.

If anything, I related to Vince, the lovelorn supermarket manager whose candle for Stuart never dimmed despite the many times it’d been spat on. Vince, the sweet Doctor Who fan who, when he did find love, was endlessly looking over his shoulder at the antics of Stuart, hoping that he’d at some point see sense. It was almost an abusive, sadistic friendship, especially when Stuart held a birthday party for Vince, and outed him to his female work colleague. Vince acts as the show’s moral compass – he’s the one that the audience, gay or straight, could most relate to. Russell T Davies explained to a BFI Q&A that he’d realised that Stuart, Vince and Nathan were one character, split into three – that we could all be as sensible as Vince, as bad as Stuart or were (once) as young as Nathan.

In fact, the one thing that people did have a shitfit about was the scene in which teenage Nathan goes home with Stuart. Nathan has already given off signals that he knows who he is and is happy …