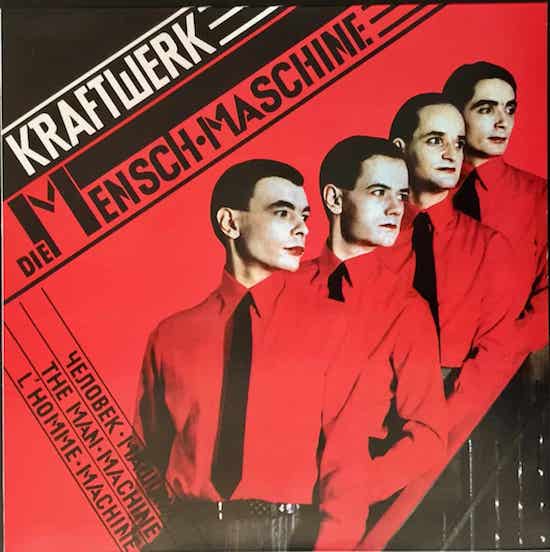

As part of the ongoing curation of their selected history, Kraftwerk will release German versions of some of their best loved albums to stream next month. Available from July 3, the records which will be available digitally are Trans Europa Express, Die Mensch-Maschine, Computerwelt, Techno Pop and The Mix, as well as the German language edition of the 3-D The Catalogue documentary. This will be a boon to hardcore fans, already doubtless very familiar with these recordings, who feel that Kraftwerk always sounded better “auf Deutsch”, more fluent, less open to accusations of gauche, risible attempts at English.

It’s interesting that, once again, Kraftwerk have declined to issue their earliest, pre-Autobahn work, as if embarrassed musically by the flared trousers they used to wear. This saw them emerge, somewhat tentatively from prehistorical, longhair jungles of Krautrock instrumentalism towards a pure electronic sound. Back then, in the early 70s, they did not deal in lyrics but their titles (‘Atem’, ‘Tanzmusik’, ‘Wellenlänge’) were all in German. This was in contrast to groups like Tangerine Dream, Can and Faust who were enjoying a degree of international success and who used English titles, sang English lyrics, minimised any potentially jarring German-ness.

All of which was odd, since all of the groups who progressed under the imposed banner Krautrock were attempting, for politico-cultural reasons, to escape the earthbound tropes of Anglo-American blues-based music, develop an open, diverse language of their own. In this, the set hierarchies of the conventional rock group were dispensed with in favour of a more collective approach, in which loops, repetition and electronic noise would supplant verse-chorus song structures and in which material was conceived in the studio rather than pre-scripted. This fresh and fertile approach to music-making was, at a subconscious level, part of a healing process, a need to reconnect with the romantic and artistic traditions of their homeland so brutally suspended by the Third Reich. This was more felt and demonstrated rather than lyrically expounded. There was at once the desire to create a music that was (West) German in origin, but also to avoid over-use of the German language, still tainted by association as it was; to de-emphasise or even do away with vocals.

According to Kraftwerk’s ongoing, touring exhibit of themselves, they trundled fully-formed off a factory conveyor belt of their own making in 1974 with Autobahn, turning the key in the ignition and hitting the road. By this point, they were developing a strong conceptual sense of their selves, in appearance and artwork, thanks greatly to the influence of collaborator Emil Schult. The lyrics to the title track of Autobahn are unthinkable in English. For one thing, you’d miss out on the “fahren, fahren fahren” line so close to The Beach Boys’ “fun, fun, fun” lyric chanted while out on their own T-Bird jolly. There’s some dispute as to whether this was a conscious allusion but it’s too delicious a coincidence to forfeit. “Drive, drive, drive”, or worse, “Travel, travel, travel” just wouldn’t have been the same. Also lost would have been the upward shimmer on “strahl” in the line “Die sonne scheint mit glitzerstrahl”; “Glitzerstrahl” is a wonderfully compound chromium-plated term born for electronic music; “Glittering rays” just doesn’t do it. In English, ‘Autobahn’’s lyrics might have sounded desperately banal, rather than thrumming with serene, neo-Bauhaus functionality.

It was only with 1975’s Radio-Activity that Kraftwerk, with the assistance of the more English-fluent Emil Schult, began to sing at least partly in English. They had acquired a sizeable Anglo-American audience thanks to the success of Autobahn, though one wonders if the more subdued response to Radio-Activity might have been down to the disconcerting shock of hearing Ralf Hütter strike up in fey and flat, wilfully weak vocals on the half-English title track “Radioactivity… discovered by Madame Curie”. There’s also the awkward moment on the punning ‘Ohm Sweet Ohm’ in which Kraftwerk’s voicebox seems to have been set to a Yorkshire accent. (“By ‘eck, Florian, reet glad to be back in Düsseldorf, like, back ohm, get kettle on.”) I’m not the only Kraftwerk fan who had to come back to Radio-Activity having heard the rest of their output.

Then there is their most famous track, ‘The Model’, whose German lyrics are as elegant as the subject matter but whose English translation, as journalist Simon Witter observed, sound like they were put together by a simpleton. “She is looking good, for beauty we will pay/She’s posing for consumer products now and then.”

By the time ‘The Model’ reached no 1 in the UK charts, however, audiences had become accustomed to Hütter and Kraftwerk’s deceptive gaucheness, understood the extent to which they were playing up to their Teutonic otherness, weathering a first wave of ridicule and Fawlty Towers-inspired mockery to have the last laugh as they laid down the electronic template for 80s pop and beyond. By the late 80s they had pretty much ceased to record new music, their work done, their reputation sealed. But this was an international triumph. If they had been affiliated to a project to create a new German music to help their countryfolk establish a renewed sense of postwar cultural identity and throw off the shackles of Anglo-American rock hegemony, then their mission had failed.

I discovered this while researching my Krautrock book Future Days when, on a train to Munich, I got chatting to a young lad. I told him I was travelling to interview members of Amon Düül 2. He’d never heard of them. No? How about Can? Faust? Neu!? Cluster? Again, polite shakes of the head. Kraftwerk? I tried? He nodded faintly but I think he was being polite. So, er – who do you like? “The Red Hot Chili Peppers!” he enthused. “A prophet is not without honour save in his own country,” spat Amon Düül’s John Weinzierl, when I related to this him.

Kraftwerk were a superb West German export; a “product of West Germany”, as they stated on their album sleeves. But another reason these German language reissues exist is to import them, and bring home a sense of their import, to German audiences. It’s not as if they are unknown in Germany – far from it – but, as with their fellow experimental travellers in the 1970s, their cultural significance, the source of pride they should represent, is still not fully felt.

In the 1980s, artists like Einstürzende Neubauten and DAF established, for all time, the advantages of the German language as a singing voice, especially in the context of electronic music, its metallic subtleties, its impact, its compactness, its silvery edge. All of that applies to Kraftwerk in German also, despite their less ostensibly brutal approach. They conquered the international market with halting English. They deserve to be heard by young Germans, in their own tongue, with all its non-translatable nuances. They deserve to be fully understood.