Before you read on, we have a favour to ask of you. If you enjoy this feature and are currently OK for money, can you consider sparing us the price of a pint or a couple of cups of fancy coffee. A rise in donations is the only way tQ will survive the current pandemic. Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours.

There is a sheen to Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. In the 34 years since its release, John Hughes’ visual love letter to Chicago seems to have buffed where its contemporaries have dulled – and escaped the critical lens that has been focused on so many films of its generation.

And why shouldn’t it? The long and short is that FBDO is a wonderful film. The touches, such as the fourth-wall breaks, tight writing, memorable quotes and a wonderful soundtrack makes the experience almost whimsical.

I find it somewhat poetic that Ferris gets this special treatment – not unlike the 1961 Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder that languishes in Mr Frye’s garage – growing only more polished in the eyes of film fans over the years.

But like the decisive boot in the car’s front-bumper, the biggest dent in the film’s bodywork comes in the form of Cameron’s unrelenting mistreatment, something that is easily glossed over by adoring fans from generation to generation.

In fact, it feels increasingly ‘meta’ that the film can provoke this kind of reaction from people. Perhaps it depends who you are as the viewer, whether you are one of the geeks, sportos, sluts, wasteoids or dweebs that think he’s a “righteous dude”. Those who hate Ferris are usually characterised as dim-witted parents and adults, jealous siblings or overzealous faculty members. It boils down to the Status Quo versus Fun – and nobody wants to be a party pooper.

Personally, I’ve never been in either camp. I love this film deeply, mainly because it works as a mirror for audiences to see themselves in a particular character – similarly to Hughes’ previous work, The Breakfast Club. He is an excellent writer of people, managing to nail them within a few lines of dialogue. We know these people inside-out within minutes of meeting them onscreen and like tables in the cafeteria, we pick who we want to eat lunch with.

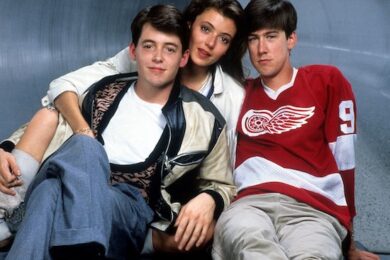

People find themselves aligned with Ferris, or see themselves as a Sloane. Or even Jeanie, who eventually comes round to her brother’s antics in the end in favour of getting revenge on Principal Ed Rooney, who effectively landed her in a police station. They are punchy, archetypal characters within teen movies – the hot but sensitive girlfriend, the plucky and wisecracking lead, the bitchy big sister, the controlling authority figure, the uptight best friend.

And it is within Hughes’ writing of Cameron Frye, Ferris’ depressive childhood best friend, who is only dragged along by virtue of his father’s glamorous sports car, that we get the main scratch within the film’s glossy paintwork. You just need to don your best Gordie Howe hockey jersey and watch from his perspective, losing yourself in the paint flecks of Georges Seuret’s A Sunday Afternoon On The Island Of La Grande Jatte.

Cameron is first introduced as the bum note in Ferris’ whirlwind plans for his Day Off. Hughes (armed with Matthew Broderick’s charm) has pulled off the performance of a lifetime, making an incredibly entitled and affluent kid seem like the scrappy underdog. The greatest injustice in his life is the fact he got a computer instead of a car, and that he is expected to attend class on a beautiful Chicagoan day. But we revel in his antics.

After all, this is practically wish-fulfilment. Who wouldn’t want to be that guy who pushes and pushes, but never pays the price? And why should he? He’s Ferris Bueller! The so-called Sausage King of Chicago.

The film plays as a series of mini-vignettes, the stakes getting higher and higher the more invested we become, until we are fully buying into the Ferris Bueller fantasy: that consequences are for other people.

It just so happens that those consequences fall on Cameron. Alan Ruck, who was 29 at the time of filming, makes his glorious debut surrounded by wads of snotty tissues. A hyper anxious teen with a talent for mimicry, he is thrown into his best-friend’s hijinks (the titular pursuit of a daycation) simply because Ferris needs a car.

And the next hour and forty-three minutes is cinematic history.

But it isn’t Ferris’ film. The character with the biggest arc and the largest stakes to lose is actually Cameron, who steals a car from under the nose of his abusive father. It is never said that Mr Frye is violent, but it is certainly implied that their household is a deeply unhappy one – a beautiful museum-like place where material worth is prized over their son. For the film, Cameron’s mother is away in Decatur, meaning the ambiguous ending lands him at the sole mercy of a patriarch who once lost it over a broken retainer.

His background is similar to that of Ferris, they are both incredibly wealthy middle-class boys brought up knowing that they are set for college – but where Tom and Katie Bueller’s oversights are firmly rooted in love, the Frye’s neglect has crafted Cameron’s neurosis. And Ferris exploits it.

Charming as he is, Ferris is a keen manipulator. His talents in weeding out the weaknesses of bar staff, teachers, parents and friends to his own benefit is what drives the plot, and he knows exactly how to dig his fingers into Cameron’s emotional bruises. There’s an entire section of monologue dedicated to Ferris’ irritation with how tightly wound he is as a result of his upbringing (the famous “lump of coal” analogy) – which quickly leads to Cameron’s coercion into the plot.

A lot of the darker aspects of Ferris and Cameron’s relationship is down to nuance, and can be easily brushed over for audience members who are happily seated at Sloane and Ferris’ lunch table. But Hughes unpeels Cameron’s character in such a way that for those of us who have had similar upbringings and experiences, it physically hurts.

Ruck plays Cameron as someone on a knife’s edge. His physicality is constantly bubbling with anxiety, white-knuckled as he debates driving to Ferris’ house – “He’ll keep calling me… he’ll keep calling me… he’ll make me feel guilty” – unwaveringly still as he imagines his father from the top of the Sears Tower.

For Cameron, there are only two notable moments of peace throughout the film. The first as he stares into the painted eyes of a child during the dream-like “please, please, please” sequence in the Art Institute of Chicago. The quickening cuts between his watery blue eyes and steadily muddying colours of the Seurat are one of the few moments of reprieve for both the audience and Cameron – where he is allowed a singular moment of deep introspection.

Whereas Sloane and Ferris have some surety in their next steps, whether that is the future or the rest of the day off, Cameron does not. We see that he is experiencing something wholly deeper than his peers, which is often a sobering realisation for survivors of abuse – especially when it comes to ‘missing’ moments in their formative years.

Another similar moment of freedom comes at the bottom of the pool when the gang discover they can’t turn back the speedometer in the Ferrari, as Cameron seems to happily wait for Ferris to ‘rescue’ him from a drowning attempt. It’s one of the only moments where we see Ferris openly worry for someone other than himself – and get a taste of his own medicine. It’s a sweet moment of retribution, which we can assume has been coming since the fifth grade.

But, the epitome of Cameron’s arc comes during the aptly named “Breakdown Scene”, when the gang realise that the Ferrari can’t be fixed and that those consequences – that Ferris has been dodging since the beginning of the film – will catch up to him here. But famously, it isn’t Ferris who takes the heat. Cameron, after suffering years of abuse and manipulation from his parents and friends, decides to “take a stand” and releases an outburst of frustration, anger and pain that even the audience can feel in their throats.

It is both satisfying and terrifying to watch the sheer scale of pent-up aggression and sadness that Cameron has been holding, but it marks the end of what we can assume is a truly toxic childhood. It also marks the end of the Ferrari – which goes hurtling through the glass garage into the valley below courtesy of a well-placed foot.

It’s a wonderful beat within the story, one that Hughes could easily have ended on, considering the film’s true ending comes too easily, too lightly after such a hefty narrative punch. It feels almost wrong to watch Ferris vault the well-manicured hedges of his neighbourhood, beating his parents and Ed Rooney to get his ultimate happy ending, while we know that Cameron is awaiting a very bitter ending of his own.

People find it easier to pick apart other titles in Hughes’ filmography, such as The Breakfast Club and 16 Candles, and rightfully so. There’s the way Gedde Watanabe’s character, Long Duk Dong is reduced to a gross racial stereotype throughout 16 Candles – and the ongoing issue of consent and persistence doubling up as comedy. In The Breakfast Club, Judd Nelson’s Bender peeks up Claire’s skirt, something that Molly Ringwald found jarring upon rewatching with her daughter years later.

The actor revisited a number of the roles that shot her to fame in a 2018 essay for The New Yorker, finding the experience a sobering one – noting certain scenes throughout Hughes’ films to be misogynistic and homophobic.

Although Ringwald emphasises that she loved John Hughes and is proud of their work, she further stressed that the films deserve to be analysed in a contemporary context – especially in the wake of the #MeToo movement: “The conversations about them will change, and they should.”

And yet, the films are momentous in their own right. Taking further notes from Ringwald’s essay, who remarked that Hollywood would never write about the minutiae of high school beyond cheesy Afterschool Specials, they did address certain aspects that hadn’t been seen – such as the feelings of young women and their viewpoint on events.

“It can be hard to remember how scarce art for and about teenagers was before John Hughes arrived.”

The Breakfast Club, with its archetypal monologues and Pretty In Pink (released the same year as Bueller) which explores social and classist themes do read like plays. Which I suppose makes it easier for us to pick at – it’s practically packaged for us to go over with a fine-tooth comb. Ferris isn’t a villian, but he is a catalyst that brings out the worst in his fellow cast members in various capers, which is an interesting choice to make for your protagonist.

For Hughes to make Cameron Frye – who should by all means stay a glum, comedic side-kick – a survivor with a higher level of maturity and understanding from his counterparts, is somewhat remarkable for its time.

This is where Ferris Bueller’s Day Off excels, in a way. It was never supposed to be a mirror to life or a social critique, but instead works as a surprisingly intimate portrait of human emotion and actions. In all their broad, brilliant, terrible glory.

And if there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s that Cameron deserved an abundance of Days Off.