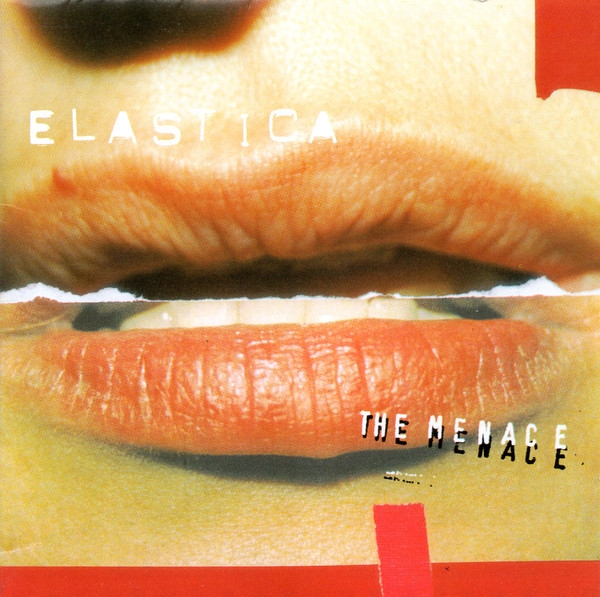

When Elastica’s second album The Menace was released in April 2000 few people – least of all the band – really seemed to care. There was one single, a short tour and a handful of promotional activities. Typical of the tone was a knackered-looking Justine Frischmann appearing on pop TV show The O-Zone, saying the album “was something we just had to get over, and get out of the way to move on.”

There was no irony or ambiguity in the title The Menace. The album, or more precisely the band’s inability to bring it together, did indeed menace all involved – Elastica cycled through band members and spent years (alongside a reputed £350,000) on tracks that went nowhere. Yet the whole process, and the people who floated in and out of it over that half-decade, left shadowy imprints on the final record, even though the final version of the album was recorded in six weeks for ten grand. The Menace, then, is an unusual combination of glacial and frantic – which is perhaps why it’s a neglected masterpiece.

I often think about the liminal space between the two Elastica albums, their much-hyped debut released thirty years ago this month, and its follow-up nearly five years later . (Deploying an architectural metaphor like “liminal space” seems apt, since Justine studied the subject and, post-Elastica, co-hosted the BBC3 show Dreamspaces). This is because, and if it’s not obvious already, I was definitely one of those few people who cared about The Menace. I had loved them for years, with pleasurable memories of their 1993 to 1995 high life. Anxious to lock in my front-row spot at an Elastica gig I once queued from 2pm to get in. Guitarist Donna Matthews spotted me, came out, told me that she liked my fringe, and gave me a sip of her Beck’s.

I should have realised, back then, that a second Elastica album might be a while coming. In the summer of 1995, when their debut album was a few months old, Elastica played at the Kentish Town Forum. I had started to hope for new material by this point. Even though they’d been famous for a couple of years, Elastica didn’t actually have that many songs; moreover, the songs were short, so they got through a shit-ton of them at each gig. I’d experienced similar setlists for months. I had a fan’s impatience for more.

A new track, just the one, was debuted that night: the never-recorded ‘Keep It On Ice’. Listening to it now – there is a live version recorded in Japan on YouTube, dating from the same month as the Forum show – it’s striking how much it sounds like their first Peel Session from 1993. Perfectly serviceable, but hardly the basis for an inventive second album.

Then Annie Holland, the bassist, left the band.

“Always change, to remain” (‘Nothing Stays The Same’)

Annie Holland is the first of several Elastica ghosts to haunt the band’s inter-album years. Holland, aloof, older, black-clad and shaggy-haired, who thought The Stranglers were too arty and not proper punk, was gone. The reason Holland gave for leaving, in August 1995, was tour exhaustion. “At Glastonbury I could hardly hold my bass, let alone play it,” she told the NME. “That’s why I looked so miserable.”

Holland was to rejoin Elastica in 1999, just before the release of the 6 Track EP; and on the back cover photomontage of The Menace, she’s notable for appearing cheerful (two teeth-baring smiles: none on anyone else). In her absence, The Menace’s bass sound was developed by Annie’s replacement, Sheila Chipperfield.

Now a DJ living in Berlin, Chipperfield’s interests lean towards electroclash and abrasive European disco: Ellen Allien, Peaches, Stereo Total. She was younge…