Before you read on, we have a favour to ask of you. If you enjoy this feature and are currently OK for money, can you consider sparing us the price of a pint or a couple of cups of fancy coffee. A rise in donations is the only way tQ will survive the current pandemic. Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours.

“It’s as if the Bunnymen were going for some ultimate or indefinable glory. A glory beyond all glories, where the gates are flung open and all you can see is this golden light shining down on you, bathing you, cleaning all the grime and shit from the dark corners of your soul.”

Bill Drummond, sleevenotes, Ballyhoo (The Best Of Echo & The Bunnymen)

Picture the scene: it’s January 8 1988, downstairs in Manchester’s Free Trade Hall. I’ve just been an unwilling if helpless part of a stampede towards a stage I can’t see. House of Hammer levels of dry ice cover up everything, meaning I’m spluttering and wondering where my legs will land. Through the tumult I can hear monkish chants that blend into a very, very loud and sustained howl of guitar, and can feel a multitude of people kicking me, or whacking me in the ribs indiscriminately.

My German Army parka is now very hot, as are my huge boots and thick woollen socks. My “Phil Oakey meets the Dulux Dog behind the Abbey Friar, Accrington” fringe means I have the same range of sight that Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson enjoyed at one of his many glorious sea victories. I am – as you can appreciate – half-blind and being rendered slowly deaf and numb from multiple layers of assault. My memory registers that 15 minutes earlier, a band called The Primitives (who’d been standing outside with flyers for their new single, called, appropriately enough, ‘Crash’), had finished their set of nice enough indie thrash to about 15 people. I mean, it was alright. All thoughts of The Primitives and standing upright and unbattered are swept away though, as I turn to face what I take to be the slow, crashing collapse of the ceiling and my impending death at the tender age of 18. No, it’s not the ceiling collapsing. It’s the sound of Echo & the Bunnymen’s superhuman drummer, Pete de Freitas, kicking out the beat to the band’s glorious doomsday chronicle, ‘Over the Wall’.

If ever a gig felt like the opening of the crack of doom, it was that Echo & the Bunnymen show at the Free Trade Hall. For, despite the euphoric pandemonium in the venue – and the mindblowing brilliance of the band that night – it really was the end of an era, a curtain drop ushering in new alliances and loves. The history books will show this as the last UK show before the original line-up split and the great Pete de Freitas tragically died in a motorcycle accident.

Within the course of that year, My Bloody Valentine, Loop, AR Kane, The Stone Roses, Pixies, Dinosaur Jr. and Happy Mondays all shuffled in and set my new sonic agenda. I even dug The House Of Love for a bit, who walked off with Echo’s sound and did okay; a Bunnymen for those who liked Merchant Ivory films. But that post punk thing really had run its course and many knew it. U2 discovered irony, The Cure patented emo, Copey became the ultimate Mother Goddess Soul Rebel, The Fall wrote some actual songs and New Order embraced both their inner football fan and their own nightclub. Echo & the Bunnymen’s old manager also knew it, pushing some mad postmodern thing with beats called The KLF. And Echo themselves, once the touchstone for all that was wild and weird, knew it too. Despite carrying on and making, for my money anyway, an okay LP with Noel Burke as singer, for many they just quietly disappeared, almost like a puff of smoke. So far so glum: just like the moody cartoon face logo on Echo guitarist Will Sergeant’s Ninety-Two Happy Customers label.

Echo & The Bunnymen artwork by Paul Simpson

Scribes of the Rabbit God

One of the aborted chapters in Charles Nevin’s whimsical book, Lancashire, Where Women Die Of Love is entitled ‘Echo & the Bunnymen: Where It All Went Forever Wrong’. The foolscap has recently come into my possession. It’s a mystery the piece wasn’t included in the original printing as the subject fits the published title, with its chapters on Southport being the model for Haussmann’s Paris, or Salford’s Frank Evans – ‘The Lancashire Toreador’ – who uses shopping trolleys as practice bulls. The lost Bunnymen chapter contains the usual charge sheet, best described as a three-page cob-on, written by a parade of ageing tracky-bottomed bad wool scribes who bemoan the fact that the band started to lose it around Porcupine in 1983 and really lost it with 1987’s “Grey Album”.

And, despite a snatch of sonic enjoyment here and there with 1997’s reunion, they have continued to lose it ever since. This sorry tale is contrasted with another aborted, ghosted chapter (pulled doubtless due to copyright reasons) entitled ‘The Likeness Of Prophetic Being’, a 5,000-page eulogy written by Guy Verhofstadt and Tracey Emin, penned in praise of the Chapman Brothers’ 345-foot tall gunmetal and permafrost statue of Ian Curtis which currently glowers over Manchester’s Piccadilly gardens, paid for by the grateful citizens of the world.

Of course, in the tradition of Bunnymen myth, Nevin’s lost chapter doesn’t exist; but it still really gets my goat. There is a long tradition of casting Echo & the Bunnymen, however lovingly or unintentionally, as the great “what if” band. This feeling of some unattainable glory slipping through their fingers is in nearly all the texts you can read about them, often from writers who are undoubted lovers and supporters of the band. Many highlight the made-up mystery, the bullshit, the fuck ups, the non-careerist aspects of the Bunnymen, and blame that “Scouse whimsy”, with the tortillas cooked on the tour bus, tours by leyline, banana fights and rabbits in the headlights.

We can cite texts from Simon Reynolds, Paul Du Noyer, Andrew Harrison and Richard King. Or Tony Fletcher’s 1987 early biography Never Stop, and Chris Adams’ Turquoise Days, The Weird World Of Echo & The Bunnymen. Then there are Mick Houghton’s sleevenotes to 2002’s glorious Crystal Days CD compilation, the beautiful 2014 Mojo article about Pete de Freitas, or its marvellous interview with Mac in 2019, by the late, great David Cavanagh. Every work at some point hints at an all-too-human, hard-luck tale of lost causes and missing the boat. The lugubrious nature of stories told by those who could take a closer look – like Bill Drummond in his story, From The Shores Of Lake Placid, or Julian Cope’s Head On – all serve to reify this feeling of astral cock-up.

Why can’t Echo & the Bunnymen escape this increasingly threadbare bad-luck tale? Why does it actually still seem to matter? Are they the Peter Cooks of classic alternative rock, continually, mindlessly cast as talented wasters? Why, for instance, can’t the band’s creative arc be properly reappraised, in the way people continually obsess over their Manchester allies and mates, Joy Division/New Order?

Before people start burning any more 5G masts in protest, this article has very little to do with my thoughts of Joy Division/New Order in a strictly musical relation to Echo & the Bunnymen. Like Ian McCulloch once rightly said, both bands are in a class of one. And anyway, if Generation Zoom, or whatever young people are classed as nowadays, are digging Toto’s mindfuck dirge, ‘Africa’, the old myth-making about Echo not “fulfilling their potential” needs to be put out of its misery, forthwith. Both bands go back a long way together in any case. The nascent Warsaw-Joy Division had its champions with the likes of Will “Manchester” Sergeant. They later shared tours, countless cans, a love of association football, recording sessions, benefit gigs and trips of all sorts together. And suffered the whims of mental managers and myth-making hangers-on, often to the detriment of their own brilliant eccentricities and “lower orders” wit.

Will Sergeant in The Bunnyhouse

Playing At Home And Hollywood Diners

So: I don’t come to praise or bury Joy Division/New Order. But I have a theory. Joy Division/New Order got the chance to soundtrack a changing Manchester to the world in a way that was never, and never could be, available for Echo & the Bunnymen and a changing Liverpool. That Joy Division/New Order’s story was later linked to Manchester’s post-industrial reawakening is Tony Wilson’s doing in many ways. Loft-living and forward-looking, on the lookout for new ways of money-making and party-going: the city of Manchester was branded from early on by Factory as its own socio-cultural project, regardless of whether the city wanted it or not. However preposterous, I loved the conceit then and I still do. Factory still needed a brilliant conduit to help sell that message, which – luckily for the label – happened to be the tragic potential of Joy Division, reawakened in the life-affirming heartbeat of New Order. (Though if pop music really did give the city a leg up, then Take That deserves equal billing.)

I’m just guessing of course, but maybe some ideas around the specialness, or rejuvenative aspects of a place were nabbed from down the East Lancs Road, from a certain B Drummond Esq in the late 1970s, and remade and remodelled to suit Mr Wilson’s wider aspirations. Nicking ideas is a genius move, of course. And regardless, Zoo and Factory methods could never be the same. The Bunnymen’s Liverpool was and is much more diffuse, mystical and shifting than the solid brick bastions of the Russell Club or FAC 51. The leyline on Mathew Street with Carl Jung’s bonce as its apex, the statue of Queen Victoria (which looks like she’s got her knob out if you view at a certain angle), Probe, the Amazon and Parr Studios complexes, Eric’s, Yates’ Wine Lodge and Ye Cracke, Brian’s Diner, the Cathedrals and the Kop. I could go on. Liverpool: a flâneur’s city mapped out, like Bill Drummond would, with the Bunny God scribbled in pencil over it.

We can see these two visions at work in their respective cities, literally through the same lens. In 1984 Channel Four ran two editions of their Play At Home series featuring the bands. Both are brilliant to watch, true documents of those times, and dead funny to boot. The Factory story is a typically cod-contentious Hollywood epic – from the opening credits a perverse set of pisstakes, set-ups and stand-offs: “Factory Records, A Business, A Partnership, A Joke.” Except, of course, it’s a smart one. Like Queen Victoria, Wilson gets his knob out, albeit in the bath whilst being interviewed by a demure Gillian Gilbert. (I would love to know Gilbert’s thoughts about that scene.)

Elsewhere, Factory musicians including New Order try to make sense of it all. What you take away is the energy, aspiration and insatiable wit of this maverick bunch running round parts of a northern industrial city. But it’s a city that doesn’t really make an appearance. By contrast (and typically), the Bunnymen played a bit-part in their show, casting themselves as “incidental musicians” and turning the whole enterprise over to their mates, such as street scribe Bernie Connors, clarinettist and saxophonist Khiem Luu and dancer and Chinatown’s CLO, Brian Wang. The main star is their favourite cafe owner and unreconstructed ex-boxer, Brian McCaffrey, and his wife Gloria. We also meet Yorkie’s mum, Gladys Palmer, who rented out her basement to the nascent Teardrops and the Bunnymen. Gladys leads a beautiful and psyched out version of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ to end the programme. This is the story of Brian’s diner on Stanley Street, where, according to Julian Cope, acid heads would go to watch the food levitate. The other star is made manifest when you watch the opening sequence and hear the splendid acoustic Bunnymen live songs; the City Of Liverpool.

Liverpool also turned up in another Channel 4 production dedicated to the Bunnymen; an edition of The Tube devoted to the band’s ‘A Crystal Day’. The programme is another droll attempt at bringing the city to a wider audience, where presenter Jools Holland seems to get in the way of everything (though sadly not the banana fights on the ferry). An intrusive Holland or not, both the Bunnymen’s Play At Home and ‘Crystal Day’ films were classic examples of that bottom-up, grassroots community fun the band were so loath to trade their reputation in on. And the sort of creative community thing that is “all the rage nowadays”, to misquote Mr McCaffrey.

Of course, it’s easier to market solidly reconstituted and postmodern brick walls outwards to a wider world (Haç, Afflecks, Dry Bar et al), than capture a fleeting spirit. And, of course, that glorious spirit can’t show its true light in these regretful texts about a band that “never lived up to its potential”. That’s a crying shame.

I Think You Are a Pig, You Should Be In A Zoo

Remember: I don’t come to praise or bury Joy Division/New Order. But I have a theory. Too many things get retrospectively labelled as prophetic or prescient with Joy Division. Joy Division’s song ‘Digital’, for instance, was once posited in a programme on the tellybox as a sign of the reawakening of Manchester and a new technical dawn. It’s as if their short-lived nature catapulted them into a sort of infinite history that can be continually garlanded. Every story about Joy Division, also, sadly, has to reach or reflect on “that” point – the one that no other band can deal with – van Munster’s Energie-Piek ijs made The Word.

As a whole it’s a gripping story beautifully told, with Deborah Curtis’s Touching From A Distance, Jon Savage’s devastating This Searing Light, The Sun And Everything Else – Joy Division: The Oral History and Anton Corbijn’s film Control, surely its most poignant chapters. Here, Ian Curtis is cast as the perfect imperfection. And, like Jesus, he continues to pull striking poses, as Kevin Cummins’ and Phillipe Carly’s fantastic photos – and server parks’ worth of digital imagery – continually remind us. The (reusable) silence around the band’s brand is reinforced with that iconic Unknown Pleasures design, ironically an energy emission we can’t knowingly experience. It’s been perfect for the unthinking 21st-century mass mindset of how we show our musical allegiances; safely touching them from a distance. How can the whimsical, sullen, all-too-human Bunnymen, with their crazed management team and extended family of chancers and cultural pirates, compete with the unbearable legacy of The Young Men and their aspic-clad singer, Ian Curtis? As I said, I don’t come to praise or bury Joy Division/New Order. I come to reflect on why their realtime soulmates Echo & the Bunnymen get cast aside as dossabouts who fucked everything up.

Back in 2001, when CDs roamed the land, pre-24 Hour Party People and T-shirt franchises, a couple of killer Joy Div live shows (Preston 1980, Les Bains Douches 1979), were released by NMC Music and whatever legal odds and ends Factory then consisted of. Tony Wilson’s sleevenotes to both contain some of his smartest lines. Wilson is at pains to point out that the band were rough diamonds – hoolies hated by the locals and prone to pissing on Spandau Ballet from a balcony. Maybe he felt this Luddite element of the band would soon be lost to sight, despite Bernard Sumner’s repeated attempts at writing lyrics. But Wilson’s “print the legend” practice has actually led to a sort of narrational stasis born of cultural landgrabs and fallouts. On a lower level, it’s a scene guarded by ageing men in branded caps, jealously guarding their “I was there in the corner” moments like Miss Marple clasping her knitting bag. These were the foot soldiers who kept the Factory flame burning, originally found in record shops up and down the Northwest. Astonishing Sounds near King George’s Hall in Blackburn, for instance. Or the odd stall on Blackburn and Burnley markets where some lad would slip you bootlegs. It was always the same reaction when Joy Division were slotted in the tape deck, these sellers were like some high priests running a finger over a sacred text, eyes closed, imbibing the moment. The message? You too can feel this for two quid. Of course, Joy Division shatter time with their music. And New Order’s music raises people up and turns them around. Anyone can feel that, no-one should deny it. They are essential bands. But, before we forget, this article is about the brilliance of Echo & the Bunnymen.

A still from ‘The Reward’ video shoot

I’ve Decided… To Roll Your Stockings Down

Julian Cope starts one chapter in his heartrending autobiography Head On / Repossessed with the following quote from Mac, from 1985. “Julian Cope? The difference between me & him is I’m a character from Shakespeare and he’s a cartoon out of the Beano.” Here we see Mac the Mouth in full flow, tripping himself up on his own hubris. The thing is, there are a lot of characters in Shakespeare. And although it’s a quote taken out of a different time, it’s one that encourages the cynic – and it’s always easy to take the cynical, world-weary view with Echo & the Bunnnymen – to draw up a long list of less-than-savoury characters Mac could play.

But here we can use Johan Cruyff’s dictum, that in every disadvantage there is an advantage. The thing is the Bunnymen really could be a set of characters from Shakespeare, or from any Elizabethan revenge play, for that matter. There is something of the theatre about them that could never be applied to their Manchester allies: playing in a line, having LP covers that acted like backdrops, the LPs themselves sounding like soundtracks for full productions. The wider Bunnymen cast is key here. The much-overlooked lost boys in this story: the late Tim Whittaker, the legendary drummer in Deaf School and late of Accrington Art College. The painter-percussionist who inspired the Theory of The Duck, a psyched-out stratagem of no meaning, but one that encouraged Bunnymen’s much-missed drummer Pete de Freitas to rechristen himself Mad Louis and spend months AWOL in the US, going off his creative nut. Whittaker: a man who described one of his most harrowing moments as having a knee-trembler in Accrington Bus Station, with a girl who continued to guzzle her bag of chips on his shoulder. Never forget the late Jake Brockman (keyboardist, roadie, biker) and Bill Butt (ace snapper, theatre-goer), both integral to the band’s defining live sound and vision, or Adam Peters (tripped-out cellist) who made one of the most brilliant records of the 1990s as one half of The Family Of God. Other characters come and go in this fabulous cast of 80s-to-90s biker yobs: Andy Eastman, Johnno, or guitarist Michael Mooney, a man whose axe skills and simmering sex appeal caused a lady friend of mine to continually yell, “Eh, you can put your thumbs UP MY BUM” at him during a Julian Cope show at Burnley Mechanics a decade later. Later there was demon drummer Damon Reece or Gordie, the night owl who’s trick was playing guitar with his teeth. All brilliant, creative and fascinating people in their own right.

There was – and still is – something Dionysian about Echo & the Bunnymen in full flow. A gang of Gabriel Ernests hanging out with Greta Scacchi and on the lookout for eternal wisdom and a bag of chips. Lunatics adrift in a Land Rover on remote Scottish islands. At their live best they could be a lupine howl, an untameable band. A sex band. A memory bubble floats back from that 1988 gig… At some point (I think during a sandblasting take on ‘Heaven Up Here’) McCulloch turned the neck of his Gibson 335 towards his mouth, and slowly felated his instrument, legs apart, gawping blindly out to an appreciative crowd. It was ridiculous, weird and doubtless replicated in some form by Mac at many other gigs, but it was very much not laddish and not scally, or Joy Divisionesque. It hinted at that strange position the band existed in: the pin-up band for initiates to a daft cult. Talking more of Mac, I’m not sure what Shakespearean character dressed as Dorothy from Wizard of Oz, or as a sort of Blanche DuBois in the band’s own ‘Seven Seas’ video. It’s hard to appreciate how he got away with it back then. In some ways, their position, inhabiting an in-between world between pop and underground, between personal ordinariness and collective uniqueness, was their commercial and reputational undoing. It’s still too difficult, it seems, to work them out.

Why did they do the things they did? Longtime Bunnymen scribe Paul du Noyer probably put it best when he said of 1997’s reformation of the original trio in Mojo: “They couldn’t live with one another. Yet they couldn’t live without. It’s a dilemma they still don’t understand, but they’ve stopped trying to fight it. This thing is bigger than the three of them, and it won’t go away.” It, whatever it is, won’t go away. I think that this admission of not knowing is as close as we’ll get to the band’s core magic, to why the idea of Echo & the Bunnymen is still a glorious headfuck. For there is something magical about their continuing existence as a band that should live alongside, not in spite of, their often brilliant and beautifully strange music. A musical legacy that (if we’re going to get all Shakespearean again) is like the “strange airs” Caliban was tuning into on his CB radio when he did time on Prospero’s magic island.

Despite the vagaries of luck and time, and of making a living, if one band shouldn’t be anywhere near the chicken-in-the-basket best of 80s circuits, or pitching halfway down a bill at any number of summer ladsladslads festivals, it’s Echo & the Bunnymen.

I asked my old pal John Robb about his thoughts on Echo and all of that. He mailed me back agreeing that: “Their only parallel band was Joy Division, who have ended up being one of the key bands, wherever you go in the world where rock culture exists. Both bands were equally groundbreaking. Both were framed by maverick managers but one had an iconic and tragic and defining young death. For some reason, rock music enshrines a martyr. The Bunnymen never stopped being great but the perfect iconic rock career seems to have to be short and sweet. There doesn’t seem to be any prize for consistency or garlands for post punk’s elder statesmen. Those that know, know though.”

I agree, John. But there again, the Bunnymen did have to deal with death in the 1980s, albeit at the end of the decade with Pete’s motorcycle accident. And later too, with Jake Brockman (also in a motorcycle accident 20 years later than de Freitas), Tim Whittaker and, later, drummer Michael Lee. Forget all the so-called past failures and career near misses, awful tragedy also follows this band.

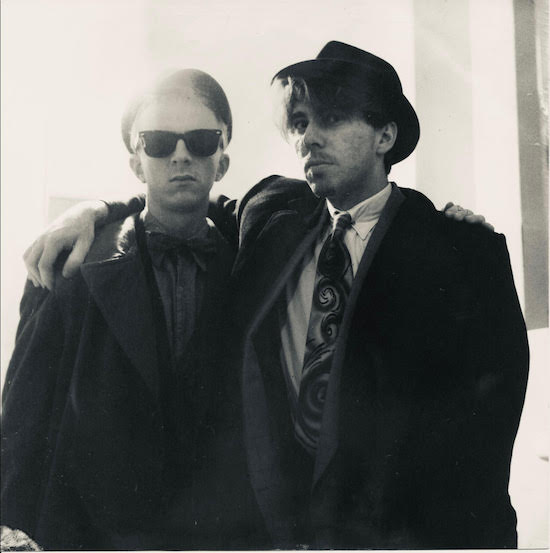

Jake Brockman and Will Sergeant by Les Pattinson

A New Hurt To Heal

“We used to have a little saying: ‘It’s not worth worrying about – tomorrow there’ll be a new hurt to heal.’”

Will Sergeant

I’ve written a sprawling article championing a band I adore and spent it, as a newly middle-aged man, seemingly whingeing at the collective memory of a bunch of middle-aged men. Is the Rabbit God leading me astray again? Like comrade Will, I still have a hurt to heal, namely: when was the last time anyone wrote at length and with passion just about this band’s brilliant music? Especially without going on about their disappointment that it’s not the same as before – just a straight take, saying the music’s just brilliant? Did the Bunnymen invoke such powerful magic back in the day that any new dose inevitably leaves a bitter aftertaste? If we’ve flattened time and accepted Toto’s ‘Africa’, why can’t we goggle anew at the Bunnymen’s incredible session for The Tube (with a vicious take on ‘Thorn of Crowns’) or stagger back in shock whilst listening to the incredible BBC In Concert recording of the 1987 Liverpool show?

The sad thing is, there are so many good things to write about their back catalogue that rarely, if ever, gets into the light. The “first four” albums are wonderful and different in their own ways. And there are many great b-sides, live takes and EP tracks that cement their legend. Then there are three glorious “late Bunnymen” LPs to plunder: Evergreen, Flowers and – for my money at least – one of their greatest releases, 2005’s Siberia, a record where we find a true reunion of Ian McCulloch’s undoubted gift for writing and singing moving texts and Will Sergeant’s titanic sound swirls.

Of course, at the time and despite some killer shows, Siberia (and one of their great singles, the prophetic ‘In The Margins’) met a lukewarm response. The blanket refrain of “it’s good, but not like the old days” shouldn’t have surprised many. Especially those who couldn’t be bothered listening in. But time has shown that Siberia is probably their greatest “late” LP; a bridge between old and new Bunnymen, with tracks like ‘Parthenon Drive’, ‘What If We Are?’, and ‘Of A Life’ serving as mnemonic bridges and answers to old questions, with their deliberate lifts from their revered Imperial phase. A very recent track, 2018’s ‘The Somnambulist’, is another proto-Bunnymen classic. Pared-back vocals that have this weird impatience or desperation to them take on a melody that crashes around between waves of memory. Yes, there are many things that don’t sit well along the way over the previous four decades, but I hope no-one has the gall to tell me Scott Walker’s The Moviegoer – or The Doors’ The Soft Parade for that matter – are their go-to jams.

The spark that really energised me into writing this piece was provided by Pete Paphides’ beautiful descriptions of the Bunnymen’s music in his recent autobiography, Broken Greek. Paphides gets the strange, restless, unformed excitement their music could cause. He captures the elemental, otherworldly nature of the early Bunnymen from a fan’s-eye view, a view from outside the inner circle, away from the press’s regurgitations. His lines are golden: for instance, the “weird demonic heat” of Ian McCulloch, the way Will Sergeant could plot a course “skywards on his own trajectory” and the utterly glorious line about Pete de Freitas’s drumming, that he could “make everything sound like an emergency”. All of this is true – it’s what they had and why you can still hear it (if you shut your eyes and listen to the Albert Hall gigs or the Shine So Hard EP). I’d only add this to Mr P’s incredibly accurate and life-affirming take, that Les Pattinson was the heart of the band. The life-giving ichor that flowed between de Freitas’s snare drum artillery fire and the brilliant, almost psychic interplay of Sergeant and McCulloch.

Who gives a fuck what people say in any case? They’re an essential band. One last thing to make the point, maybe, courtesy of a very clear memory of that 1988 gig. At some point, Mac decides to tell the audience who the “best bands from Manchester” are. Many in the crowd yell The Smiths, Smiths! (Oh little did we know)… This provokes a scornful smirk. Mac pretends to think, pouts and lists off the following. The Hollies, Buzzcocks, Herman’s Hermits, The Fall… and… New Order. Cue chaos. Someone gets on top of the stacked amps behind Les and jumps into the front row. No-one catches him, what a div. Will and Jake ignore it all and busy themselves invoking crushing waves of sound, Pete thunders on and Les and Mac kick each punter off the boards, smiling each time they launch another back into a fermenting mosh pit that, given the fug, hairspray fumes and last wisps of dry ice, increasingly looks like a cauldron of homebrew being given a stir. Looking back, it was beautiful. And the music’s still there.

Peter Hook, Will Sergeant and pal

Author’s Pick: Top 10 Lost Bunnymen Cuts

‘Rollercoaster’, 1986

A lost classic (a probably underplayed demo b-side to ‘Lips Like Sugar’), this is one of Ian McCulloch’s finest moments for me, employing the wild, teenage vampire vox that was normally saved for his live outings. You can hear similar whooping vocals on the brilliant Albert Hall versions of ‘Do It Clean’ or the track ‘Porcupine’ on bootlegs of that LP’s 1983 tour. I know Mac has recently slated his old singing style, but tough. This is my party.

‘Angels And Devils’, 1984

Another bloody b-side – to ‘Silver’ if you please – this is one of the greatest tracks the band ever made. De Freitas’s glorious tub-thumping, tom-tom beat, Les’s bubbling bass and Sergeant’s sparkling guitar give this track a real mystery that’s only heightened with some of my all-time favourite lyrics.

The Litter: Action Woman, 1985, released 2002

The radio recordings of 1985’s mini-tour of Sweden are just glorious; the band playing off practice amps, high off local hooch and mostly playing covers of their favourite songs. It’s impossible to break down these shows into highlights but ‘The Midnight Hour’ and ‘Action Woman’ are mine. ‘Action Woman’ wins it for the false ending and a scorching vocal. Apparently Pete de Freitas hated the whole thing. Now: what happened to that other Liverpool band who tried to get back to basics?

‘Ocean Rain’, Peel Session, 1984

I find it impossible to choose between this salty, scally proto-La’s take on ‘Ocean Rain’ or the stately galleon that slowly brings the greatest album ever made to a close. They are both utterly beautiful in ways that probably need a high priest of postmodern nothingness to explain.

‘Heads Will Roll’, 1983

Porcupine is a weird LP. Lots of dudes think it’s their best, certainly as time has passed. I’m not convinced, but as a psychedelic outing, the LP is up there with Lindsay Anderson’s 1967 film The White Bus. This gloriously aggressive track, (along with its sharp-toothed brother, ‘Ripeness’), is how the Bunnymen sound when the acid patterns start making sense.

‘Of A Life’, 2005

I could have chosen the entire Siberia LP, as it’s easily their greatest in recent times, but will settle for this particular song swirl that presses out its message like a hammer. Closely followed by the gloriously itchy ‘Sideways Eight’, where the guitars rub and scratch along like sandpaper.

Shine So Hard EP, 1981

It’s impossible to choose a track from the four recorded here, as each is an absolutely incredible take on the original songs. In fact, it’s hard to listen to the LP version of ‘Crocodiles’ or the two Heaven up Here tracks after listening to these. As ever, Les Pattinson’s bass-playing is borderline heroic. Buxton Pavillion was, for that night, the omphalos of the known world.

‘What Time Is Love? Echo & the Bunnymen remix’, The KLF, 1990

OK, I’m naughty for picking this, but a great remix from when time had stopped for Echo & the Bunnymen. Will Sergeant’s guitar runs like a razor through this track and adds new insight to The KLF’s vision.

‘King Of Kings’, 2001

A lovely bubbling song that serves up an easy side dish of psych with chips as an extra. It’s a typical cut from one of their best “lost, late” records, Flowers. The ‘Read it In Books’ line, “who wants love without the looks / fucks?”, meets its more sanguine (if equally assured) older brother: “Met Jesus up on a hill… he confessed I was dressed to kill…”

‘Colour Me In’, 1997

A barnstorming track with the very slightest whiff of Electrafixion’s heavy guitar sound. Listen to Pattinson’s bass line, too… it’s like a tank at full speed. When I heard the ‘Nothing Lasts Forever’ b-sides (‘Watchtower’, ‘Polly’, ‘Antelope’), I was convinced they were onto something special. I really wish the band had gone further with this sort of sonic assault.