Before you read on, we have a favour to ask of you. If you enjoy this feature and are currently OK for money, can you consider sparing us the price of a pint or a couple of cups of fancy coffee. A rise in donations is the only way tQ will survive the current pandemic. Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours.

You join us in the second half of the 1990s, where a youth is trying to pin down the perfect cultural artefacts, from the limited pool accessible at that time and place, with which to garnish his own meagre personality through fandom. Few things he finds fit the bill better than the work of Chris Morris, a ‘cult’ British broadcaster in the tradition of many things described as ‘cult’, which is to say enviably respected and popular. The important thing is that it’s not, for example, TFI Friday or Fantasy Football League, rather something that allows the youth to believe this implicitly elevates him above his peers.

The youth, as you probably gathered, is me, and while I’ve not really maintained Chris Morris acolyte status in later years (am yet to see his second and latest feature film, 2019’s The Day Shall Come), twenty-something years ago I was a right teenage fanboy. Despite arriving slightly late for the original showing of The Day Today, Morris’ first work for TV, in early 1994, by the time its successor Brass Eye was announced two and a half years later I was in front of the screen with my metaphorical scarf and rattle for the first show in the series. The only problem was that Channel 4 got jittery and postponed it at a late stage. Cut to the writer of this piece, blessed with neither internet access or anyone who might have informed me of the show being pulled, sitting through ten minutes of an old Whose Line Is It Anyway? episode announced as “a change to our scheduled programming” before admitting to himself that this was not Morris roguishly toying with the audience’s expectations, but an actual episode of Whose Line Is It Anyway?. Cringe.

One eventual upside was that Brass Eye’s rescheduled transmission date, between January and March of 1997, gifted fans a new Morris vehicle only eight months later. Blue Jam was his return to Radio 1 – where he’d hosted a weekly show shortly after The Day Today had ended, during a period where the station was attempting to mount the comedy bandwagon as part of a proposed reinvention. These efforts having faded out, Blue Jam was Radio 1’s sole ‘comedy’ programme at that point. Why ‘comedy’? Well, on first contact, an uninitiated listener could be forgiven for scarcely recognising it as an example of the form.

Broadcast from midnight to 1am on Friday night-into-Saturday morning (Morris wanted it to start even later; me, let’s just say I passed up some social opportunities to record these onto cassette), the three six-episode series are meticulous studio creations, where music of a broadly electronic and leftfield nature blurs into sketches whose dialogue often unrolls at a Beckettian plod; monologues whose blank, medicated calmness belies what’s being described; and jingles which portray various Radio 1 DJs of the time as mutants or perverts. In the light of day, it’s clear that Blue Jam’s head creator is aiming to make people laugh, sometimes with fundamentally crude material – but a fitful weekend shut-in, giving themselves to the dial in lieu of uninterrupted sleep, would have been in prime spot for discombobulation.

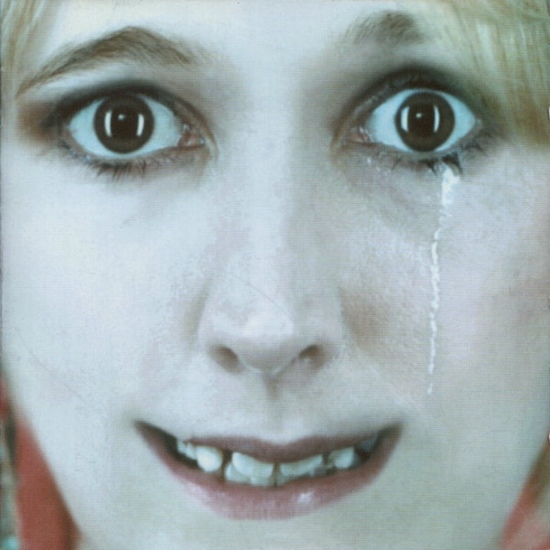

Weighing up Blue Jam, and its legacy, 21 years after it finished is a task requiring nuance. Certainly, it was successful on its own deliberately limited terms – none of Morris’ other works made it to a third series – and won a Sony Radio Award in May 2000, for whatever that’s worth to anyone outside the industry. The ‘best of’ CD released by Warp Records later that year sold well, and many among his more devoted fans consider it his finest moment. Overall, though, I’d imagine that Jam, its single-series TV adaption which also arrived in late 2000, enjoys the greater recognition factor: partly due to being screened before bedtime, partly because of radio’s baked-in cultural ephemerality. Its content, even prerecorded like Blue Jam, is liable to fall into a memoryhole (Morris has approvingly called radio “a place where you can quietly get on with things”), and compared to Brass Eye or The Day Today it’s generated precious few catchphrases or memes, but at its best the show is still without peer or parallel this far down the line.

Is this, then, most correctly attributed to the vision of Chris Morris or the state of 21st century comedy? It’s by no means been a static form for the last two decades, but changes in medium, budget and audience sensibility haven’t fostered a creative space that would allow something like Blue Jam to thrive now. The nocturnal listening concept doesn’t count for much if one can listen whenever it’s convenient; execs are increasingly less minded to take a gamble on an out-there concept (and the chances of anyone at the increasingly timid BBC allowing Morris his desired level of editorial control, where tapes were handed over so close to broadcast as to make censorship by higher-ups impossible, must be sub-zero at this point); surreal, edgy and otherwise dark material is plentiful, but generally brash and ostentatious, the better to grab an audience whose multi-device consuming habits reward quick setups/payoffs over subtlety.

I don’t wish to dwell too long on other shows and the (mostly limited) extent to which they might bear comparison to Blue Jam, though. Nor, for that matter, is there that much mileage in looking at the respective career arcs of Morris, and his various coworkers and contemporaries in British comedy, since the twilight of the 90s. Suffice to say that on a case by case basis there are some dispiriting developments, be that in terms of their product or their public image, and these usually have something to do with an eagerness to exist online and spout every opinion that enters their head. To this end, the credits for Blue Jam’s writers and voice actors encompass dull, reactionary twerps, someone who has sheepishly noted that his right-leaning views put him at odds with “most creative people” and so largely keeps them to himself, one of the most relentlessly loathsome individuals in contemporary British public life, and those who appear to value privacy over their platform, Morris himself being very much in this last category.

This means that anyone attempting a critique of his work is forced towards the proverbial separation of art and artist: we simply don’t know enough of Morris’ life away from the controls for it to meaningfully inform one’s take on Blue Jam, or whatever else. (When Brass Eye stirred up controversy in 1997, and again in 2001, tabloids attempted to drain his past for hatchet-job profiles and came up virtually empty-handed.) No-one’s work exists in a vacuum, but this state of affairs feels much more pleasant than the one where everything Ricky Gervais brings out is viewed through the prism of his aggravating attempts to cast himself as a free speech avatar.

What Morris clearly can’t avoid are the bald facts of his identity, which are much the same as Gervais’ and only as relevant as you deem them to be. That relevance, in turn, might depend on how much stock you hold in the maxim that comedy, or satire, should only punch up. While this isn’t new as an idea, to all intents and purposes the phrase appears to be a post-millennial one, and if you’re steadfast in your belief that people more marginalised or of lower social status than the humourist are inappropriate fuel for that humour, then Blue Jam includes plenty of difficult moments. Much of his prior work, especially Brass Eye, contained a plausible deniability in this regard: insensitivity towards sexual abuse victims or people living with AIDS, yes, but in the service of dunking on the absurdly self-important prurience of television’s news and documentary wings. Morris’ return to radio certainly didn’t forego satire, be it of people, beliefs or events, but nothing as concrete as an ethos is ever present to fall back on.

Having grown up in a medical family – Morris’ father Michael was the village GP, his mother the GP’s secretary – it’s hard to resist the temptation of grasping this rare biographical detail and linking it to Blue Jam’s litany of sketches set in a doctors’ surgery. The show’s doctor, also named Michael and voiced brilliantly by David Cann, has the surface-level air of respectability that’s often lent by a cut-glass southern English accent, while being incompetent or obnoxious every time he has to attend to a patient. After his introduction in the very first episode, where his habit of kissing body parts for curative purposes is apparently seen as normal by the afflicted, the focus shifts slightly: the world’s mores are as we understand them, the doctor’s are not. The extent to which he, with only meek objection, can thus proclaim one patient too ugly to examine, mask having forgotten how to do his job by sending others to the shops, or man a phone sex line during surgery hours sends up the authority conferred by the power imbalance in such a setting. Or, to consider it from another possible angle, it doesn’t intentionally do this at all, and the writers’ primary aim here was just to bring their “imagine if…” riffs into being via sublimely sharp, natural-sounding dialogue.

One deviation from that last rule in the ‘doctor’ sketches takes the form of Michael being assigned a patient with a suspected pulled tendon and using this as a pretext for insulting his colleague in colourful terms. “Decent people are coming in here every day to listen to such a bawling fart ravine. Jesus H rubber twat ball! And you didn’t help matters, joining in on his side,” he chides the nonplussed visitor, “you little wankywindow.” This sort of linguistic japery runs through just about all of Morris’ work, getting heavy absurdist mileage from minor adjustments to what we see as conventional turns of British-English phrase. It’s also one of its most poorly aged elements, on account of its legacy (along with Malcolm Tucker in The Thick Of It) being that dismal style of compound swearing used by people who never quite grasped how or why swearing is effective. The cockwomble set, if you like, or ‘shitgibbon set’ if you happen to be reading in the United States.

Still, irritating as this may be it’s ultimately pretty harmless – not, by and large, the rhetoric of bigotry or toxicity. This brings me to a short sketch titled ‘Little Girl Balls’ on the Warp compilation, in which a couple introduce themselves and their young daughter.

Father: We’ve always had a strong feeling with Judy that she’s really a 45-year-old man, trapped in the body of a four-year-old girl.

Mother: So she’s had an operation to fit her with the penis and testicle glands of a 45-year-old man.

Judy: Mummy, can I…

Mother: Shhh.

Father: Look at that. It’s perfect.

Mother: We’re particularly pleased with the balls.

This vein of amusement has increased resonance in 2020, but not in a good way. Specifically, it echoes two popular transphobic attack lines: the alt-right-beloved “I identify as an attack helicopter” yuks, which seek to equate the farthest fringes of 2014-era Tumblr with gender dysphoria as a whole; and the notion that trans or nonbinary kids are being manipulated into their identities by selfish, progressive parents. These concerns, for want of a better word, have proliferated in recent years, an unpleasant byproduct of increased trans visibility – which is to say that it strikes me as unlikely Blue Jam, at a time where these issues were simply not commonly understood tropes, was singing from the same spiteful hymn sheet. Rather, I imagine nothing more sinister than writing-room absurdism gussied up into 80 seconds of dialogue, while also suspecting that if Morris and Warp had to reselect a CD’s worth of material this one wouldn’t make the cut.

Despite what the worst tendencies of the modern discourse might imply, there’s a happy, wide medium between “it was a different time, nothing to see here,” and “historical context is irrelevant, only today’s politics matter,” so please don’t mistake this as my big push to #CancelChrisMorris, or think that I am at all invested in tallying how many Times He Was Problematic. Not only is it valuable to be able to sift produce using our knowledge of its period, it’s also rewarding. Blue Jam, again, contains multitudes, its pieces equal parts timeless and timely. So while The Day Today and Brass Eye made hay as John Major’s Conservative Party pedalled their clown car onward to the electoral abyss, Morris’ follow-up show is stoutly New Labour-era, finishing in February 1999 before the wheels had loosened on the Blair premiership.

Beyond the basic fact of doing their lampooning at the time of a Tory administration, his pre-‘97 works were never politically partisan, but over about nine hours’ worth of original material I don’t think Blue Jam even mentions any contemporary political figures. Much of it exists in a curdled netherworld which couldn’t be farther away from parliamentary goings-on. Morris having gone to unusual effort to sucker MPs into promoting fictive bollocks for Brass Eye segments, it’s not hard to figure why a tactical retreat seemed so appealing. Conversely, it was never likely to be the case that he would make things easy either for himself or Radio 1’s Matthew Bannister, who commissioned him, and especially not when Blue Jam’s gestation was punctuated by the death of Princess Diana, an event which had the effect of drugging an entire country in one seatbelt-shunning swoop.

From a resulting total of four Di-themed bits, roughly two and a half were broadcast. A Brass Eye-esque interview with grubby royal biographer Andrew Morton mainly relies on weirding out its subject but does yield one highlight, Morton condemning nonexistent video games with “All you’re doing is exploiting somebody’s death” (and Morris’ exquisite “mmm” in response). The testimony of a man who claims to have identified “a profane message” in ‘Candle In The Wind 1997’ when played backwards, was included in the second episode, seemingly without issue; a subsequent gambit, later titled ‘Bishopslips’, is the source of greater infamy due to apparently being removed from the air during the moment of transmission. Cutting up the Archbishop Of Canterbury’s funeral address into moderately silly or naughty phrases, a la Negativland, it hardly seems possible now that a station, likewise a nation, were so consumed by the vapours. Morris lore has it that a third sketch, known as ‘Doc Rude’ and genuinely offensive – albeit in the tradition of comedy injoke ‘The Aristocrats’ – was scripted in the knowledge it was unbroadcastable, with a view to smuggling ‘Bishopslips’ past the censors by making it seem relatively benign. (There’s at least one other documented incident of Morris employing this tactic, which incidentally has also been used by the post-2010 Conservatives for policy announcements.)

The bits of Blue Jam which most strongly evoke the late 90s, without being ‘topical’ per se, are the monologues. A man, voiced by Morris but whose name we never learn, recounts his experiences blundering into catastrophe while his mental faculties are ravaged by either too much or not enough prescription medicine. Oftentimes, this happens in the depths of London’s art and media scenes, his main link to which is Suzy, an impressionable socialite he’s known since childhood. So it is that an artist encases him in glass with rotting offal to form an installation praised by Will Self; gakked-up actor Tony borrows his belt for a stranglewank that curtails a house party; and a craving for cigarettes ends with Jovler, the writer of “the most devastatingly accurate play that will ever be written about sex” demanding our narrator watch Suzy “being plugged by me” in exchange for one.

The final monologue, where he is tasked with giving Suzy away on her wedding day in place of her late father, underlines a growing sense that this is another construct more readily frowned upon nowadays: Morris’ narrator, a nice if irreparably damaged guy, ‘zoned by a friend both shallow and sluttish via a succession of braying pricks. Not that we’re expected to consider someone who sleeps in a house with no windows and pawns his corneas to buy shoes a worthy suitor, in fairness. Jovler’s intention to write him into a play as “a man so ugly the audience finds it impossible to feel any sympathy for him” is impressively metatextual (as Jovler would probably say).

Nathan Barley, a Chris Morris/Charlie Brooker collaborative sitcom which ran for one series in 2005, underperformed ratings-wise but has since sealed its place as the canonical pisstake of London new media grotesquerie. Funny as it often was, I never really felt like either of its creators had a close enough affinity with that world to properly nail its intricacies. However, advocates often credit it with predicting the future in some way, such as Nathan uploading vicious pranks to his website years ahead of the worst YouTubers (but also years after other people on the internet did the same thing). Morris (ditto Brooker to a lesser extent) has accrued the sort of reputation where people jump at the chance to point out how this or that occurrence is like something from one of his programmes, which is all very well but has a habit of not noticing that newspaper subeditors raised on The Day Today are giving screwball stories headlines clearly intended to evoke it. On the other hand, there’s the ‘Street Sausage Vendors’ monologue, which is from 1999 and whose premise – the narrator is writing a magazine article where he has to eat a huge amount of grilled streetfood to establish which stalls will make you sick – is dead-on Vice-during-its-transition-from-edgelord-to-performative-wokeness-era stuff. The punchline, which involves him getting screwed over by a more established writer followed by the mag’s editor, hasn’t aged a bit either.

Blue Jam sketches may be deeply moral, but are not morality plays and are often absent of moral acts. Most characters, recurring or otherwise, are either malevolent or unprincipled, or marks at the mercy of the aforementioned. Sometimes the dreamstate feel makes this rule beside the point: Mr Ventham, voiced by Mark Heap, is the show’s gentlest multi-episode figure, his scenes the most foggily Lynchian (more so when reprised for Jam – not every sketch transferred to the visual medium wholly successfully, but this one absolutely did). He calls into an office, where he’s evidently a regular visitor with a pay tab, and asks for help with trifling hyperpersonal tasks, like working out where he’s left his wallet. David Cann’s character suggests Ventham look in the kitchen, bills him £45 for the pleasure and adds, “Help yourself to a button on the way out. Might come in handy on a jacket or shirt.” At no point do we resent the business for this outrageous grift, or for that matter mock the presumably monied Ventham for outsourcing his functional abilities. You could treat it as class commentary, if you really wanted to, but I’m sceptical that was the intent.

How much leeway should a supposed retreat from the binds of conventional ethics give the creators of these scenarios, who remain incontrovertibly in a world still bound by these ethics? How much give is in a piece of string? Thresholds of offence in comedy – the marker between speech that’s permissible, and not – is an infinitely large and unresolvable topic where the only certainty is that anyone claiming certainty is untrustworthy. I chose to write about Blue Jam because it has a certain personal element for me, and this website’s Low Culture series allows for the personal, but I do so with the assumption that the placing of my red lines is not that interesting to others. Yet it’s naïve, at least if you have any below-surface interest in comedy, to think it follows that no-one else’s are of any relevance either. Channel 4 got some 2,000 complaints, a record at the time, after screening Brass Eye’s ‘Paedogeddon’ episode, so even if you suppose that many of those were from Mail-reading planks who didn’t watch it, they certainly had a bearing on the national conversation. You could hardly claim his reputation suffered in the longer term, mind. Chris Morris is about as close as it gets to a living UK comedy untouchable; even those in his stanbase of the opinion that he’s not done anything properly great since ‘Paedogeddon’ don’t really hold it against him.

Should you find yourself debating the merits of Frankie Boyle, David Baddiel or Little Britain – and could any prospect make you miss the company of friends more? – it’s a safe bet that in good time, the nasty shit they once said, wrote or wore on their face will come up. They’re never going to completely outrun it. I’m not soliciting sympathy here: it’s their own fault and they all have banknote-stuffed pillows to cry into. I am however positing that the lack of interest in dredging Morris’ back catalogue for similar retroactive condemnation (such as, I don’t know, doing blackface a couple of years before Baddiel and a decade or so before Matt Lucas) owes much to his retaining of professional dignity. It probably shouldn’t work that way, really – we ought to be capable of mulling dubious artistic decisions unaffected by our thoughts on the person behind them – but the guy who has never written a weekly column for the Sun, backed out of calling Martyn Ware a vile troll upon realising he’s a quasi-public figure, or compered a charity dinner arranged with the express intention of allowing diners to sexually harass waitresses certainly seems to have put himself in an advantageous position here.

If he hadn’t done, and instead spent his downtime firing off inane tweets about there finally being a grown-up opposition, we might have already had a Conversation about a sketch from the third series where a woman seduces her new neighbour under the pretence of him checking her breast for lumps. She slaps him, calls it “pretty much an assault” and things escalate to the point where she’s phoning the police while trying to initiate sex. (It was redone, slightly less explicitly, for Jam.) An albeit exaggerated spin on the ‘vengeful female manipulator ensnares her dupe of a man before tossing him to the wolves’ scenario that vexes MGTOW types, or whatever they called themselves in 1999, whether you interpret the sketch as a satire of such attitudes or a regurgitation of them might well depend on how much good faith you bring to the Blue Jam table.

Weird, then, almost irreconcilably weird, that ‘Unflustered Parents’, the sketch I’m hereby calling the show’s best ever, contains no identifiable target and is sincerely, content-warningly horrible. To a sonic backdrop of some organ-driven exotica number, Cann and Julia Davis (who has cultivated an enviable reputation of her own for quote-unquote dark comedy, and who apparently found this close to beyond the pale) realise Ted, their six-year-old son, is several hours late home. “He probably just decided to stay overnight at the school,” rationalises the dad, with a yawn. Ted’s abduction and murder, which they accept is the most likely eventuality after another fortnight of absence, is a minor inconvenience – this isn’t their singular deviance, rather they appear to live in a culture where this is how people operate.

As conceits go, there’s nothing inherently inspired about “what if the most fucked-up things… were actually normal”, nor does ‘Unflustered Parents’ harbour signposted social comment (although if Cann and Davis’ characters didn’t code as middle class, I fancy we’d have quite a different angle on this). It’s the pitch-perfect sense of the tics and rhythms of real-life speech that make this compellingly shocking rather than indulgently so: this is a detail a lot of comedy either falls short on or eschews, and where Blue Jam consistently drills down (the unflustered parents feature three more times in total, with the sanctity of human life the common missing factor). Morris has said at various points he doesn’t consider his work satire, and while this might be a bit like how goths never want to be called goths, you do imagine that writing something which wasn’t expected to have a point would have been a freeing experience at the time.

Speaking to Jon Snow last year in the course of promoting The Day Shall Come, his views on the fodder which fills the post-Brass Eye void attracted some attention. “I think we’ve got used to a kind of satire that essentially placates the court. You do a nice dissection of how things are in the orthodox elite, and lo and behold you get slapped on the back by the orthodox elite.” Cue speculation as to who he could possibly have been shading – yet I wonder if this is a more empathetic take, noting that ‘the court’ is wiser to the game now (or more arrogant in its belief of unimpeachability). Plenty of news’ big dogs loved The Day Today, after all.

Perhaps in decades to come, this quote will have ascended into the canon of tart wit-on-wit summaries, alongside Peter Cook’s one about 1930s German satire doing so much to stop Hitler and Mark Twain’s about analysing comedy being like dissecting a frog. Perhaps the belief that our words can never beat the bastards, and we’re wasting our time thinking about it anyway, will by then have been finally, finally cemented. An entire artform sunk into insular despair, punctuated by dirty jokes. Whereupon people can dig up Blue Jam, in all its uncomfortable excellence, and at last have a point about how Chris Morris predicted the future.