Night after night she lay alone in bed / Her eyes so open to the dark / The streets all looked so strange / They seemed so far away / But Charlotte did not cry… – ‘Charlotte Sometimes’ (single) – Robert Smith/Penelope Farmer

Charlotte Sometimes was one of the first books to make me think about myself growing up. It brought to mind the younger person I used to be, approaching adolescence, navigating the constant fracturing and rebuilding of my identity. It also made me realise that this was a process I never fully left behind, that I would, I will, never truly escape.

I was in my late twenties to early thirties when I bought it, on a trip to Bristol to see my baby brother, James, eleven years my junior, who was six when I left home, but now was suddenly, miraculously, at university. I’d gone to the Oxfam second-hand bookshop in Clifton to donate my Chaucer companion and a few anthologies of poetry and plays from my English degree. I’d struggled with the idea of giving them away as ten years earlier they’d been a big part of who I wanted to be: a fish out of water in a fancy old university trying to look clever. I didn’t want to feel like her any more. I wanted to cut off that character, become someone else.

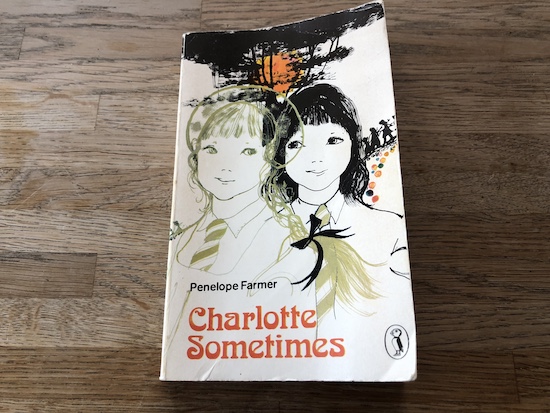

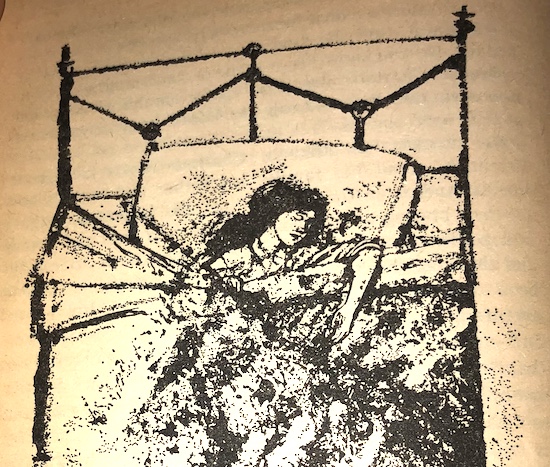

On the same day that I left them (or they left me), Charlotte appeared on the top of a bookcase, facing the front window. This version of Charlotte Sometimes was the very first paperback edition, published by Puffin in 1972, with two girls on the cover, drawn in sparse pencil strokes – one black, one dull gold – by Janina Ede. The drawings inside by another illustrator, Chris Connor, were similarly woozy: a girl on a bed in inky blotches, others at strange angles, their faces barely defined.

Of course, the reason I bought this in the first place was The Cure, a band who for years had nipped at the edges of my imagination. It began from when I was a messy adolescent, a combination of high temper, introversion, squareness, being scared. At fourteen, I’d found The Cure’s lyric book, Songwords, on the shelves of Gorseinon Library and took it out again and again; a few years later, I bought their early singles compilation with an HMV voucher from my grandma in the post-Christmas sales. I was fascinated by the black-and-white photograph on its cover, of retired fisherman John Button, his face wind-and-wet-weathered, the different stories in his life almost speaking through the wrinkles, folds and jowls. I lived then for these serendipitous real-world encounters with unusual, diverting expressions of pop culture, knowing how the radical act of going into a library or a sales section with the little pocket money you had could result in magical moments of chance and choice, moments that could expand or recalibrate your blossoming mind.

The first track on Standing At The Sea, as its 1994 CD reissue was called, made me realise how music could suck up a story’s sense of unease and convey it entirely in sound (I was studying Albert Camus’ L’Etranger for my French A-Level, and ‘Killing An Arab’ suddenly made me more interested in it). I didn’t realise then that track nine, ‘Charlotte Sometimes’ had arrived from somewhere else too – and that Smith and the author of the book that inspired it, Penelope Farmer, eventually met.

Charlotte Sometimes was published in 1969. It’s the third part of a trilogy of books about two sisters, Charlotte and Emma, the first being Farmer’s debut, 1962’s The Summer Birds, the second 1964’s Emma In Winter.

In The Summer Birds, the two sisters befriend a mysterious invisible boy who teaches them and their classmates to fly. He later tells them they can be children and fly forever if they are happy never to return to their loved ones. They decide not to, but one girl from their class, in a startling leap of Penelope Farmer’s imagination, an unhappy orphan, goes with him anyway.

In Emma In Winter Charlotte is sent away to boarding school, and Emma is left behind. Emma starts to have the same dreams as her classmate, a boy called Bobby, in which they travel back in time, further and further by the night, to the beginning of the world. Time is described in the book as “being like a coiled spring, which can be pushed together, so that some moments in time can be very near a moment in another time”. This idea moves into a different realm in Charlotte Sometimes

.

The light seems bright / And glares on white walls / All the sounds of Charlotte sometimes / Into the night with Charlotte sometimes – ‘Charlotte Sometimes’ (single) – Robert Smith/Penelope Farmer

Charlotte, aged thirteen, is at boarding school for the first time and is the first girl to arrive. Asked by an older, curious prefect called Sarah what bed she wants to sleep in in a dormitory called The Cedar Room, she is drawn to a bed near the window with ornamented spokes on its wheels. Sarah encourages her to take it, and then keeps “staring out of the window, swinging the window-cord, remote-seeming and separate”. It seems as if she wants to say something important, Charlotte tells us, but even though Sarah will become an important character much later in the story, here she represents a sense of everything being pregnant with possible meaning when you’re an adolescent, trying to read signs of how to act, direct your life, steer a ‘proper’ way onward.

Charlotte instantly feels discombobulated, removed from herself. She writes her name on her new books in her best handwriting, as I remember doing myself as an adolescent, to try and feel firmer, bolder, older (“Charlotte alone proved no identity at all… Charlotte Mary Makepeace she wrote it full and in her best handwriting on each of the different coloured exercise books given to her”). She then goes to sleep, having “felt to be so many different people” since that morning. The next morning, she wakes, to find the building outside her window is gone. Instead, the light is filtered through a huge and dark cedar tree, and soon a younger girl is calling her Clare, thinking she is her sister.

It is no longer the late 1950s, but 1918, with the First World War still going on. “It must be a dream,” begins the second chapter, a few pages before Charlotte rushes to the mirror, only to see herself looking exactly the same as she has always been. The next day she is Charlotte again, Clare having taken up her place in the future; the next day their places switch again, the timeslip continuing nightly, Charlotte and Clare writing each other letters in a hidden notebook until Charlotte gets trapped in the past with Clare’s little sister Emily (who works out what’s going on very quickly, in a lovely detail of fraternal sensitivity).

Many details also follow about secrets and strange tales, amplified by the wartime setting. Charlotte and Clare lodge with a family whose son Arthur has been killed in the conflict; we are steeped in the colours and sensations of living in the late 1910s. Later in the book, there is a seance, the celebration of armistice, the coming of the Spanish flu. Notions of loss build around Charlotte’s engagement with the past, but she also realises people she knows at that time may still exist in her present. (Now in early 2024, I’m also put in mind Andrew Haigh’s recent brilliant film fantasy, All Of Us Strangers, another timeslip masterpiece, watching a character going back in time, confronting ideas of horror and death, while still ostensibly being themselves. I’m thinking what a moving experience it is to watch or to read someone do the impossible while making it seem through acting or writing to be entirely possible.)

It also strikes me now, re-reading Charlotte Sometimes in my mid-forties, that Farmer brings the novel’s peculiar atmosphere to life in great sensory detail. Her descriptions of locations and experiences are beautiful, spectrally eerie, often menacing, pretty gothic. It’s no surprise how they became bleakly fertile soil for The Cure. “The drenched earth outside smelt clean and bold as a knife,” she writes of the different smell of 1918, shimmering in the shadow of the cedar. When Miss Bite reads the class register forty years in the past, the effect on Charlotte feels like “the buzz of names and answers are not echoing from the roof so much as disappearing slowly, melting, like the sounds in a vaulted church.”

There is also a line very late in the book when Charlotte is meeting someone from her past, now all grown up, that reveals a landscape sucking and soaking up its characters’ raw, blighted feelings. “They turned away across a bleakness of earth and bonelike grass, where even that sun could scarcely raise a colour”: what a startling, discomfiting line. It seems timely to add that there is a strange absence of passion, sexuality or any meaningful desire in these pages. Clare is a prim, proper girl. Charlotte is also always thinking about others, their concerns, their feelings, over hers, and there is a lot of dissociation in her head, a lot of tears.

Shuddering between intense sadness and numbness, these emotions are the foundation of the book’s shivery, innocent power. I wonder if Charlotte Sometimes speaks to me strongly because my childhood was so fractured, so cut short; I remember feeling I had to ‘grow up’ very young, to deal with my father’s early death. But this book also makes me think of how childlike I was for so long. It reminds me of how every night, my mind racing so much I couldn’t go to sleep, I would immerse my whole face in cold water, holding my breath for as long as I could, just to feel something simple and pure and uncomplicated. It reminds me of a day early on in secondary school when I told myself, you will remember this day forever, this inconsequential day, when you tried to stall time.

I still remember making myself that promise, and a certain bright coldness in the air, but don’t know if it was autumn or spring, nor can I remember the rest of the scene’s colours or contexts. Still, I do remember its feelings. Its cold, bleak, sad feelings.

There was something disconcerting about a book that had her own name on it, that no one ought to have written except herself, and yet that she had not written. Nor was her name now her property alone. – Charlotte Sometimes (novel), Penelope Farmer

Robert Smith first experienced Charlotte Sometimes when he was twelve, listening to his older brother, Richard, a huge influence on his cultural life, reading it to him. Penelope Farmer wrote about this in a blog she maintained for six years in the 2000s, Rockpool In The Kitchen – Smith had told her about it when they met.

In two entries, The Cure(d) Part One and Part Two, Farmer reflects on the book published in the year she turned thirty. She was now sixty-one. “[My] whole book turned – though I didn’t see that when I wrote it – on identity,” she wrote on June 9th, 2007. “How do people identify you as you?” She also talks about having an older twin, Judith; the sisters in her book were not identical but similar-looking, and “quite different in character and ability”, just like the characters of Charlotte and Clare. “This was another connection I did not make at the time I was writing,” she writes. “The book would probably have worked less well if I had.”

Charlotte Sometimes became Farmer’s most successful novel, but she didn’t realise how much until one of her children came home from school in the early 1980s, and told her about a song that they’d heard. She recounts going out, buying the single, with its lyrics printed bold as you like on the sleeve, many of them straight from her book, without credit. Her agent is informed, and they start to pursue the band legally, but Farmer begins to enjoy her novel’s strange afterlife, plus “it was doing wonders for my sales – and adding somewhat to my fan mail”.

Her second post recalls the evening in May 1995 when she went to a Cure gig, getting free tickets after her agent convinced the band’s management that they weren’t going to sue them. “And yes, if I came early and went backstage”, Farmer writes, her tone a perfect balance of waspishness and delight, “I would be allowed to meet Robert Smith himself.”

Her account of the night is full of sprightly, sharp observations, particularly about the time she spends with her niece backstage before the show, waiting for the band to turn up. And then they appear: “It was not until almost time for the sold-out concert to start that the whole of The Cure sloped in between two of the screens; sloped really is the right word, I promise you – slouch might have been near too; but ‘slope’ is better.” Some of them clutched instruments, she adds. “They had quite a lot of hair between them.”

Then Smith wanders over to Farmer, clutching his Puffin paperback in his hand, the same edition I bought many years later in Bristol, with the two little girls on the cover (“the only girly-looking edition of the book ever, and the very last one I would have expected him to be holding”, she notes). Smith tells her how the novel.“never got out of my head”; Farmer notices how line after line in the book is underlined in pencil. “’You see how inspired I was,’ Smith said, adding behind his hand, looking at me sideways, ‘how I nicked it.”

She also writes of how The Cure play ‘Charlotte Sometimes’ in the encore, how Smith announces the author is with them tonight, how the lights swing around to pick out her and her niece in the crowd: “I got up, put up my arms, waved my hands about and acknowledged them; the first and – certainly – the last time I’d get that kind of buzz, the kind rock stars are used to, but writers most certainly aren’t, even the best-known ones.” Then the chords “swelled up again”, she adds, “the cheers faded and I sat back and listened with everyone else to what was by now, even to me, something deeply familiar, even effecting in its way. My tune you could say; yes, really.”

Farmer kept writing after meeting The Cure. Her later books include 1996’s Penelope: A Novel (“Penelope only wants to be herself, but in order to achieve that she has to look to her past and discover just who she really is”, runs its blurb), anthologies about twins, sisters and grandmothers, her free-flowing blog (I especially like how she writes about death and sex) and a 2015 novel, Goodbye Ophelia, inspired by the early deaths of her mother and twin, in 1991, from breast cancer. In this fascinating interview with book site Vulpes Libres, she discusses that she’d self-published it after mainstream publishers turned it down for being too “quiet” and “reflective”, or not knowing how to “re-establish her” as an author.

I emailed some of her former publishers to try and see if Farmer is still active and writing: three emails have been met with no reply. If you’re still out there, Penelope, I still hear you.

And, she thought uncomfortably, what would happen if people did not recognise you? Would you know who you were yourself? Charlotte looked up doubtfully, wondering why, as she got older, she seemed to be more afraid of things, not less. – Charlotte Sometimes (novel), Penelope Farmer

I felt a pull to return to Charlotte Sometimes in the last year, and, at first, I didn’t know why. As I read it, I realised that the act of writing my book The Sound Of Being Human, presenting my life on the page, solidifying slippery memory in ink, had made me question the many versions I’ve created of my identity. Also watching my son growing up – he is ten in a few months – makes me think of the little person that I was, who crossed the bridge between childhood and adolescence, how my identity is still constantly fracturing and rebuilding.

I am someone who has always tried to fit in, who has always felt strangely out of whack, whose accent has long morphed unconsciously between Welsh lilt and flattened Estuary as I move between my South Walian village beginnings and my more mature, urbanised professional life. It’s funny how you think you’ll outgrow that unease when you’re older, but the ever-present present keeps you locked in its hold, tunnelling you forward through time, distancing you from you once were in some ways, while you also remain, somehow, you.

All versions of our lives leave things out – trauma, buried feelings and desires, rolling internal monologues – but in Charlotte, you hear that unease, one she articulates to the reader directly and powerfully. In The Cure’s take on her story, this unease becomes epic, shivery pop music, something to be sung along to and shared. For me, through this strange metamorphosis, Charlotte remains a conduit for things people want to do, things they want to say, for the confusion and sadness they feel, that still returns, as the little voices inside keep piping up in their older, wearier bodies.

There is also a moment in the novel’s final pages where Charlotte knows she is returning to the present day, and despite her “excitement and pleasure”, she is “filled with a huge kind of nostalgia”, listening to the gaslights fizzing outside, being allowed a moment to say goodbye to her old life. But then time passes, and she is unable to say goodbye to someone she cares for very much – and the night falls, as it always does, and always will, and another day begins.

The book ends with the term ending, and the children on the bus home, fittingly enough, singing an old song. Time goes on. Time always will. But sometimes I dream.