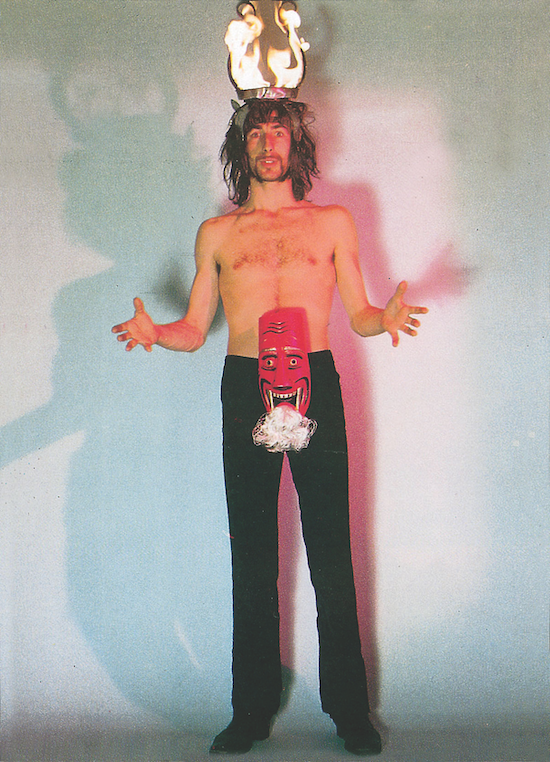

Arthur Brown, courtesy of Cherry Red

I was 15 when I became obsessed with the gifts of the Holy Spirit. These superpowers from God were the most exciting things that could be bestowed on a diffident teenager growing up in a Cornish backwater in the late 1980s. Prophesying and performing actual miracles were next-level endowments for proper holy people, though I was convinced I could speak in tongues, confidently babbling in a crowded prayer meeting with other evangelicals in a language that felt instinctive and was freeing to unleash. This didn’t stop nagging doubts at the front of my mind that I was making it up. Also not in my bag of charismatic tricks was the lesser-known gift of interpreting tongues, as everyone else sounded as though they were indulging in echolalia too, especially the church pastor, whose speech resembled the repetitive patterns of Twiki the ambuquad from Buck Rogers In The 25th Century.

And then there was the discernment of the spirits. I had this in abundance, because I saw devils everywhere. I became convinced that demonic possession was as widespread as the common cold, and I longed to drive out evil spirits at the coalface of exorcism. The church I attended was a large, dynamic Methodist chapel. Built in 1814, it opened its doors four decades after John Wesley laid the foundations of Methodism in the south-west at large rallies in places like Gwennap Pit, an outdoor amphitheatre 20 miles east of Penzance. Hellfire and brimstone in West Penwith had been in short supply since the late 18th century, but now all around the church there was talk of revival, with a new strain of evangelicalism imported from across the Atlantic. Billy Graham did one of his crusades via satellite, beaming live into our church, and heathen friends who I’d invited from school responded to his appeal for souls and were prayed over by bearded men in plaid flannel suits.

Everything was so simple then, with a clear bifurcation between good on one side and evil on the other. The universe was split into two distinct camps: heaven and hell, righteousness and wickedness, good health and disease, with everything I learned at church equating to goodness, and everything that was outside of that equating to badness perpetrated by the Devil. Revelation talks of the 144,000 saved, and I took that number to be literal. Murderers and child rapists were probably damned, sure, and then there were the non-believers, believers in other religions, believers in the same religion who were doing it slightly differently, those who hadn’t asked for forgiveness, parishioners in our own church who hadn’t been washed in the blood of the Lamb, and so on…

Into this world one day dropped a vintage video repeat of The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown showing on MTV, creating holy apoplexy in my living room and in my brain. On the videotape of my mind’s eye, the performance of ‘Fire’ is flushed with psychedelic Technicolor like the lobby of hell, though that may have just been the receptors overloading in my brain. I suspect it was the famous Top Of The Pops performance from 1968 that I was watching, all sinister chiaroscuro and high camp, with Arthur barking the immortal “I am the God of Hellfire!” line as flames lick the fork protruding from his helmet, and fire consumes the foreground too. There is a colour version with flames in hues of purple and orange, or it might have been their performance on the Beat-Club, the influential Bremen-based German pop show, with drummer Drachen Theaker in a creepy translucent mask. The show, incidentally, was where Hans Joachim Irmler of Faust cut his teeth as a runner, and one presumes he was taking notes about using extravagant props in performance from the sidelines.

‘Fire’ startled me, and it would have been met with shock by TV audiences in 1968. Brits, who were viewing in black and white, were still living in the long shadow of the war and still attending church in significant numbers. Flower power was of interest to the cultural tastemakers and all the rage on a few streets of central London, but it resonated far less with the bemused general public, especially if they didn’t buy records and weren’t interested in fashion or recreational drugs. It’s easy to forget what a huge cultural figure Arthur Brown was in the year he became internationally famous, and just how risqué ‘Fire’ was at the time. Both he and Jimi Hendrix had their own song called ‘Fire’, written as the napalm dropped on Vietnam, though Brown, in his sacrilegious robes, was perhaps even more a divisive figure than Hendrix. There was nothing utopian about lyrics like “you’re gonna burn” either; it was dark and appeared to be kicking against the hippies. Retrospectively, it could have been a premonit…