At the final of the 2024 PDC World Darts Championship, 16-year-old rank outsider Luke ‘The Nuke’ Littler came within a whisker of a historic victory. Any disappointment had to be dealt with quickly – no sooner had he stepped off the stage at Alexandra Palace than he was jetting off to Bahrain for another competition. As one sage commentator observed on Radio 4’s Today programme this was something the teenager from Warrington, who’d still netted himself a tasty £200,000 for losing, was going to have to get used to. A gruelling life of first class air travel in glamorous locations awaited him from now on.

Littler-mania caused many, myself included, to reflect on the last time darts crashed into the national consciousness when, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the likes of Jocky Wilson and Keith Deller became household names. This revolution had happened quickly after after ITV’s World of Sport had broadcast the News Of The World Individual Darts Championship from Alexandra Palace in 1972. As with snooker, another bar-room game with historically shady connections to illegal gambling that had made the leap into people’s living rooms, it was the arrival of colour television at the fag end of the 1960s that finally made darts a viable small-screen spectacle. It began racking up the ratings from the mid-70s onwards, when the BBC also picked up on the sport and one time Grandstand producer Nick Hunter began experimenting with multiple camera angles. By utilising two cameras and a split screen, it was possible to simultaneously show both the board as the darts thudded into it and the player on the oche, every emotion flashing across their face as they lobbed each arrow. This relatively simple technical innovation kept the viewer locked into the action, with no confusing jump cuts between board and thrower. It helped ensure that millions tuned in to see nail-biting contests between the likes of the ‘man in black’ Alan ‘The Ton Machine’ Glazier and the diminutive Welsh master Alan ‘The Arrow’ Evans. A golden age for the game on the box (and clearly for men called Alan) was duly ushered in at a point when UK television audiences were still limited to just three terrestrial channels.

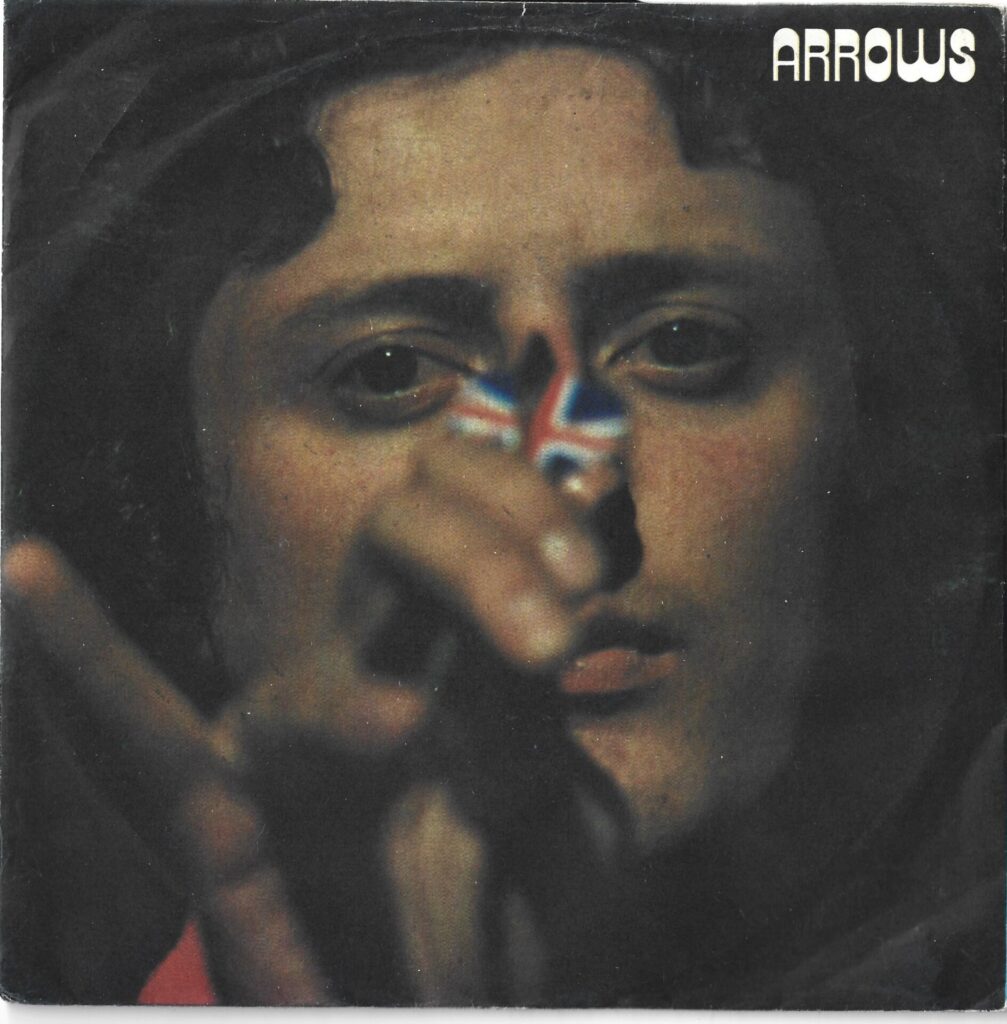

The reporting on Littler’s rapid rise to fame late last and early this year brought images flooding back of an earlier icon of the game hauling himself around Britain on slam-door British Rail Trains, all royal blue and tartrazine livery, with a reassuring quantity of interior woodwork. Those images, almost arc-welded into my retinas after seeing them fleetingly years ago, were from Arrows, a peerless documentary (currently up on the BBC’s iPlayer here) about Eric Bristow made at the very moment when his career was on the brink of going stratospheric.

Shot in 1979, when the self-styled Crafty Cockney was only twenty-two but already considered one the best darts players in the world, was the work of the Kilmarnock-born filmmaker John Samson. A working class radical Bohemian, Samson served an apprenticeship on the shipyards of the Clyde where he became politically active in trade union strikes and protests against nuclear weapons. Taking up photography (and the guitar), he fell in with a more raffish Glasgow Art School set and went on to study at the London Film School in the mid-1970s.

As a documentarian he was drawn to demimonde special interest groups and unfashionable hobbyists. Perhaps his best-known, or most-quoted, film is Dressing For Pleasure (1977). This profile of rubber and leather fetishwear aficionados includes incredible, if much-re-used, footage of Malcolm McLaren and Vivian Westwood’s Sex boutique on the Kings Road and its sales assistant-cum-figurehead, Jordan Mooney – the Mondrian-make-up sporting beehived Valkyrie in …