Before you read on, we have a favour to ask of you. If you enjoy this feature and are currently OK for money, can you consider sparing us the price of a pint or a couple of cups of fancy coffee. A rise in donations is the only way tQ will survive the current pandemic. Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours.

“It’s one hundred years from today and everyone who is reading this is dead. I’m dead. You’re dead. And some kid is taking a music course in junior high, and maybe he’s listening to the Velvet Underground because he’s got to write a report on classical rock & roll and I wonder what that kid is thinking.”

This is how musician and author, Elliott Murphy began his sleevenotes to one of the greatest albums ever released, 1969: The Velvet Underground Live. It’s cheering to note, that at the halfway mark, the sprightly and well turned out 70-year-old is still with us and living in Paris. As for the band line up featured on the album, rhythm guitarist Sterling Morrison joined the silent majority in 1995, and singer and lead guitarist Lou Reed died in 2013, leaving just drummer Moe Tucker and bassist/organist Doug Yule still fighting fit.

Hang on, did I just say Doug Yule? Does it even count as a Velvet Underground album – let alone “one of the greatest albums ever released” – if Doug Yule is involved? I think we need to spool back a bit.

This is an article concerning The Velvet Underground – a band who have already had far too much written about them. (Only 10,000 young music writers read Lester Bang’s clear insights but all of them went on to write something inferior.) In order to compensate for this, I will attempt to approach the group from a very non-canonical angle of attack. This article will commit at least five heresies. The first is that it will throw shade at the reverence bestowed upon their most well known (and to the majority of people, essentially their only) album The Velvet Underground And Nico; second, it will question the merit of the input provided by Nico who sang on three of those tracks; thirdly, it will be dismissive of the role played by initial “manager”-cum-patron Andy Warhol; fourthly (and this is the point where I need to consider deactivating my social media accounts) I will state forthrightly that I don’t think White Light/White Heat is their best album either (this sentiment also applies to The Velvet Underground and Loaded in case you haven’t already worked out where this is going); fifthly – and perhaps most gravely – it will extol the virtues of Doug Yule. This foolhardy course of action will, perhaps reasonably, be taken by many as a veiled attack on John Cale, even though he is a musician who I actually consider to be brilliant. Regardless, this will be used as an excuse by an angry mob to drive me from my home, and force me, weeping, into the sea.

Now, if at this point you’re already feeling angry, that makes two of us. What is this rot I’m talking?! This feels like a symbolic attack on everything that is heroic and aspirational about rock music, while championing the remnant dunderheaded dross.

No Warhol? But he represents the weirdness, the queerness, the damn art. You don’t have to peel slowly to reveal how important he was in creating a liberating yet protective space for VU to gestate then explode inside of. Rock & roll is only worth a shit when it collides with art, with weirdness, with queerness, surely. Despite Lou Reed being the most prominent member of the Velvet Underground, it was initially Warhol who flew this particular flag for the group. He acted as a conduit to the world of Ondine, Paul Morrissey, Edie Sedgwick and Brigid Polk. It should be noted that Reed, who wrote the song ‘Heroin’ before founding VU, was a seasoned transgressor by mainstream standards. When he realised he wouldn’t be able to persuade John Cale to share his bed, he cajoled him into sharing heroin and hepatitis instead. But in Lacanian terms the Factory was Reed’s real mirror stage and Andy Warhol would be his mirror.

No Nico? Surely she was the real European gravitas of the group, the initial ballast they needed to secure them before pushing outwards. It’s a matter of opinion of course but The Velvet Underground And Nico sounds like a mad man’s breakfast to me; sonically it’s a great anthology or compilation rather than a cohesive LP that hangs together well, no matter how brilliant most of the individual tracks. It’s clear that neither party were completely comfortable with their cut and shunt marriage, thrust on them from above. Perhaps, if Reed had relented and let Nico sing ‘Sunday Morning’ so there was a bit more balance, the creative relationship might have been more harmonious. He clearly didn’t want her on the album however, and I can’t help but suspect that this antipathy between the former lovers helped Nico honk herself all the way to a quarter tone flat across most of ‘Femme Fatale’, ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror’ and ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’. She wasn’t really a natural nightingale at the best of times, apparently due to a perforated eardrum, and what you hear on this record is her best take after some serious practice. There’s something bordering on cruel, listening to Nico’s original demos for the VU, to the extent that I won’t even link to them here.

When you hear the band’s chanteuse deal with the lines, “Here she comes, you better watch your step”, the emotion provoked isn’t a subtle fascination, a complex attraction, but a literal spasm of panic because she’s bellowing like a 3am housebreaker brandishing a crowbar. Nico became, of course, a singular and brilliant (if occasionally unpleasant) artist not long after this album came out and her working relationships with the various members of VU would change dynamically over time. By the 1968 recording of The Marble Index for example, her relationship with producer John Cale was if anything worse than it had been the previous year. According to him at least, her issues with singing in tune had not improved but creative solutions were sought and he played a small but essential role in facilitating a masterpiece. This naturally makes you wonder what The Velvet Underground And Nico could have been like had they been given time to gel creatively and had their collaboration not been one primarily of commerce. Nico’s appearance on the debut album was essentially a non-negotiable clause in the generous management deal that Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey were offering the group. Reed saw it as a bitter pill he simply had to swallow – hence his attempts to minimise her appearance on the album the second the ink was dry on the contract. But The Marble Index, Desertshore and The End… shield Nico from all attacks: they show that she was right to be convinced of her abilities and perhaps even suggest that Warhol knew what he was doing all along.

No John Cale? But he was on a different plane to everyone else, the true gateway to the avant-garde; the band’s connection to the worlds of Tony Conrad, Stockhausen, John Cage and LaMonte Young. The smart could perceive this. To what extent did Irmin Schmidt lean on this idea of sonic triangulation when he breezed through NYC in 1966? These were connections sensed as a living lattice of possibilities when others couldn’t even see the dots, let alone join them: "If I could just push this idea to its logical conclusion. Uptown and downtown. Classical and modern. Avant and mainstream. But I need some black to go with this overwhelming white. The super in sound and the far out noise. I can do it. I can. I can. I can."

This vital connection wasn’t severed when Theatre Of Eternal Music percussionist Angus MacLise quit The Velvets in 1965. He was annoyed that they had been offered $75 to perform live – the dirty taint of commerce! Thank god he didn’t live to see the Banana merch on Etsy. But the connection was hacked away decisively in late 1968 after Lou Reed gave Sterling Morrison and Moe Tucker the ultimatum, “Cale goes, or there’s no more Velvet Underground.” And even though it was obvious to everyone that they needed to get in line behind the only brilliant songwriter of the group, it was clearly at the cost of losing the member with the true Promethean creativity. Cale understood Reed more clearly than anyone else. He was the only one who could match the singer’s earthy skill with their own fiery strategy, their resultant spark rocketing the project skywards – stage one; stage two; escape velocity. Glitter and flash decorating the void. And everyone seemed to know this bar Reed. Was it his greatest creative mistake? Quite probably.

The Velvet Underground rebrand themselves as a good ol’ rock & roll band, Polydor

So when they lost the overt queerness; the press-worthy, monied art connect; the oil-projection lit happenings; the long, boring films that everyone was talking about but no-one was watching; the berserk transgressive weirdness; the seat at the NYC avant-garde table; the literal jouissance (picture Gerald Malanga creaking in new black leather as he supplicates himself on all fours at the feet of Mary Woronov; kissing her boots, licking the hilt of her bullwhip as Reed intones “Strike dear mistress, and cure his heart”). When they lost all of that, what were they actually left with? Four people who knew, odds were, they had already fucked their big chance. Or, to be more charitable, they knew, chances were, their big chance had been fucked for them by feckless scenesters, shark-eyed art bastards, and cluelessly out of touch record label dolts. Four people suddenly in a mad panic – switching up to crisis management mode – trying to rebrand themselves as a good ol’ rock & roll band: “We’re gonna have a good time together! Na na na na na na! Na na na na na na! Hey! Hey!”

Urgh. Could there be anything worse!?

But – and this is the problem with attempting to cultivate and maintain a universal cultural theory, while demanding music retrofits to your carefully styled aesthetics – none of this distracts from the fact that the Velvet Underground played the best music of their career post-Warhol, post-Cale and post-Nico, in a period of just six months towards the end of 1969. Why not much of this late 60s brilliance translated into actual studio recorded material is the subject for another feature perhaps but suffice to say, for me, the proof of their ascension lies squarely in the form of a series of live recordings – which genuinely show Velvet Underground at the height of their powers.

If you’ve already heard one of the documents I’m talking about, then chances are it’s 1969: The Velvet Underground Live. It’s my favourite VU album, although it wasn’t the first record by the band I ever heard.

When I started secondary school in the early 1980s, there was a kid in my class, whose (relatively, for St Helens) bohemian parents had a copy of White Light/White Heat. The British Verve release with the negative of the WWI soldiers on the cover. Don’t worry: I’m not going to pull a Gillespie or an Ashcroft and pretend I was bang into this noisy album when I was 12 – I wasn’t… at first. What actually used to happen was this. My mate had cats who would slide through his compact Thatto Heath terrace, luxuriating on Afghan rugs thrown over the family’s massive sofa while his parents listened to Jeff Beck, the Stones or Dylan (or Off The Wall if his sisters were home), nuzzling in the faint hash haze. But one day my mate said, “Watch this la”, as he put ‘The Gift’ on the stereo, and the cats immediately reconfigured into hissing, upside down ‘U’ shapes and boinged, angrily out of the room with claws extended never once losing their rigidly arched integrity. It was cruel. It was hilarious. We did it once a week for the next year and slowly, inch by painful inch, I accidentally built myself a solid base from which I could comfortably recognise that ‘Sister Ray’ was a work of sheer genius. And that is how I became a teenage Velvet Underground fan. Not because I was cool but because I was a roughneck goon with an ambiguous attitude to the comfort of animals.

White Light/White Heat is a great album of course – only an idiot would claim otherwise – and it certainly sounds more like a cohesive whole than its predecessor. Unfortunately it also sounds like it was recorded in a shed by a partially deafened psychopath. Which is fine, I guess, because the incoherence of the recording reflects their incoherence as a group. A furious document of Reed and Cale conspicuously uncoupling. ‘Sister Ray’ is an astonishing and revolutionary audio document… the title track, well, less so. Gary Kellegren told the band that all of the jerry-built electronic equipment they’d rigged up and the severe volume they were playing at wouldn’t work as they had pushed everything into the red but the band told him simply that they didn’t care and Kellegren, an accomplished producer, was shouted down. This was a huge mistake because people like him exist to interpret the kinds of idiotic demands rock musicians dream up (everything louder than everything else) and find sophisticated solutions, instead of being gophers to carry out literal orders. White Light/White Heat is exactly the kind of record that will stop a schoolkid dead in their tracks; and should rock & roll be concerned with anything above and beyond this? But as much as I was frozen dead to the spot by my exposure to this brain-churning noise, a long period of time would elapse before I ever saw a copy on sale in a shop that I could afford to buy.

So the very widely available 1969 was the first Velvets album I owned, and it was the first I loved unequivocally. It was a posthumous affair, released in America in late 1974 and probably intended to cash in on the fact that Lou Reed was, by that point, famous. Transformer had already become a keystone of any hip young glam fan’s collection and Sally Can’t Dance had reached number 10 in the US chart earlier that year. 1969 didn’t come out in the UK for another five years, arriving just as post punk was cresting. White Light/White Heat had been the post punk’s VU album of choice. ‘Sister Ray’ was, after all, the ideal song for a band like Joy Division to play live when they were trying to cement their own tough & heavy vision of what their group should be, away from the scenius of Wilson, Cummins, Morley, Hannett et al; here were the hench young men, flexing their muscles. A heavy sulphate rager, which can be heard on Still; ignore the daft vocals, it’s northern post punk powered as much by lo-grade acid as it was by cheap amphetamines; as much in debt to Hawkwind and the Stooges as it was to the Sex Pistols and Pere Ubu. This is probably quite close to how the band felt they should be appreciated without all the icy, spectral mither and art.

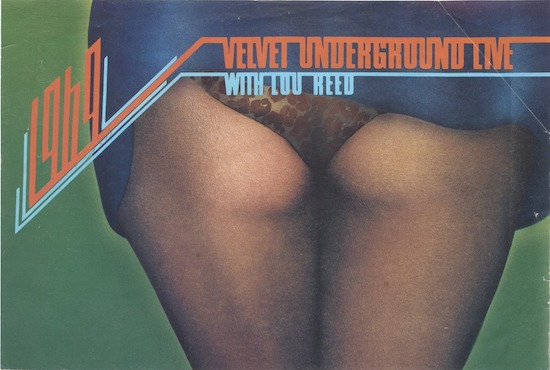

But the arrival of 1969 as a new release in 1979 with its powerfully trance-inducing, minimal grooves, probably didn’t hurt matters when it came to exempting VU from any Maoist punk edicts about 60s music that were still floating about. Either way, the live LP made more sense than the debut in those heavily revisionist times – no dreamy ‘Sunday Morning’ here, the last suggestion of folk rock crushed under an endlessly cyclical amphetamine chug of guitars. It did the group the same favour the Julian Cope compiled Fire Escape In The Sky did for Scott Walker just two years later. A process of recontextualisation in order to remove the signifiers of a different age. That said, Cope’s idea to absent Walker entirely from the packaging of Fire Escape and house his superbly curated anthology in a tastefully textured card sleeve, so it looked like an early Simple Minds record or something Factory [Manchester] would have put out was a genius move and a million miles away from the almost transcendentally awful sleeve art of 1969. A poorly rendered and proportioned oil painting of a woman’s lower half seen from behind, complete with high heel boots and skirt hitched up to reveal leopard print knickers, it’s genuinely on par with the forlorn oil paintings one regularly finds abandoned, along with vestigial traces of hope and innocence, in Sue Ryder or Mencap. It might be tempting to assume the aesthetic blight of the cover was due to major label rush or disinterest, but the sleeve was created entirely by Ernie Thormahlen, Lou Reed’s tour manager, who rose to torrid minor infamy as the ‘before and after’ model on the rear of the Transformer sleeve. Is the sleeve actually supposed to be Ernie’s lower half? It doesn’t matter – it’s still terrible. I celebrate this album cover though because it is the real reason I found it easy to score a second hand copy for next to no money during the height of the hard-left leaning, puritanical indie pop era of the mid-80s.

This skyscraping album is a document of a band who were forced to become brilliant in order to survive. This isn’t simply a case of the right time/right place luck of the bootlegger. Sterling Morrison claimed dismissively that they had played shows ten times as good during this period. The Velvets had to spend a lot of time on the road because they had no money – they were notorious not successful. MGM paid them about $200 a month to live on and they didn’t get advances or see much in the way of royalties. Moe Tucker lived with her parents in Long Island while the band were recording their third album and she had to take a part time job in order to keep her head above water – rock musicians reading in 2020, should at least take some cheer… Gigs were an obvious way to get cash in hand – and even then it didn’t amount to much more than “pocket money” after tour expenses and equipment were factored in.

In the second half of 1969, the band played away from home nearly every weekend, either returning to NYC to recharge midweek or staying away for a localised mini tour or residency if it was further afield, say, California, Texas or Canada. Their MO was to stick rigidly to locations where they knew they had a real or potential constituency rather than committing to a comprehensive tour. “Why play Toledo, Ohio, where no one knows you and where people are not likely to be the least bit receptive?” said Morrison to Victor Bockris for the Uptight biography.

The Velvet Underground get ready to hit the road in 69, Corbis

But in cities such as Dallas and San Francisco, anyone could book The VU. The End Of Cole Avenue, was a tiny Texan club owned by a rich kid who just happened to love the band so he booked them for a run of six nights. That’s all it took. The tracks were recorded on reel to reel by another VU fan who just happened to be a sound engineer. His recording of the first night was duff and the kind of thing that only completists are going to want to track down. But the band became aware of what was going on and invited him to set his equipment up on stage for the following night. The results were so good that four of the 1969 tracks, including a slightly countryfied ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’ and a beautiful early outing for ‘Pale Blue Eyes’ were captured during the October 19th set.

Even though they were a notoriously spiky band, it wasn’t unknown for friendships to spring up between them and the would be documentors. Robert Quine was a budding rock musician (destined to become a Voidoid seven years later, no less) and hardcore VU obsessive who first taped the band at Washington University, St Louis on May 11, 1969, on a Sony tape recorder with handheld microphone. He moved to San Francisco later in the year, which was lucky for him as in November his favourite band rolled into town to play a month’s worth of gigs. At first they set up shop at a large hippie-friendly venue called The Family Dog before switching to the smaller but better kitted out Matrix Club across town, and Quine attended nearly every show with tape recorder in hand.

As there were so few people there at the start of the residency they couldn’t help but notice him and began to put him on the guestlist. They warmed to him and would give him a heads up if they were about to play a setlist rarity such as ‘Black Angel’s Death Song’ and after gigs backstage they’d occasionally ask him to play one of his tapes back to them so they could analyse their performance. He ended up hanging out with the band on their downtime and getting invited to their rehearsals as well. Before you say, ‘That’s pretty lucky for a fan’, well, Quine actually ended up becoming Reed’s lead guitarist for four years in the 80s, debuting on The Blue Mask in 1982. You can hear what we should assume is the best three and a half hours’ worth of his 1969 recordings spread across the discs which make up the The Quine Tapes V. 1-3 – and these include such rarities as the adrenalized New York anthem that never was, ‘Follow The Leader’.

The best of the Matrix material didn’t come to us via a bootlegger though. The club was run by a musician (Marty Balin of Jefferson Airplane) for musicians and they had an actual four track tape machine installed into the house mixing desk as part of the sound system. Bands were often given tapes of their performances at the club and (after much legal wrangling) notable live albums from The Doors, Steppenwolf and Big Brother & The Holding Company playing the club became commercially available. The Velvet Underground’s residency lasted for several weeks but the Matrix house recordings were made over just two days, 26th and 27th November, with two sets per day. Afterwards the tapes were mixed down to two tracks and then given to the band. After VU eventually ground to a halt, their former manager Steve Sesnick tried to sell the tapes but Lou Reed’s management company stepped in, seized the audio and organised the official release 1969 – hence the singer’s name plastered on the front cover.

Some people grumble about the sound of these recordings and it’s clear – if you’re listening to 1969 at least – that at some point, the tapes were transferred to acetate as you can hear surface noise in several sections. And if we’re going to acknowledge the rank spectre of audiophilia for a second: maybe avoid the CD version and go for the vinyl if it’s an option, as the former was recorded straight from the latter, and not mastered from the acetates or the original tapes for a CD or digital release. Although one of the CDs does contain a spectacularly nuts version of ‘I Can’t Stand It’ not contained on the vinyl, so maybe you should just get belt and braces about it like me, and go all in for both.

The truth of the matter however is that there are hundreds of bands out there who spend month after month in studios, burning obscene amounts of money in post production, slaving over pro-tools, computers and mixing desks in the pursuit of a chimerical fidelity when they should actually be meditating on the fact that it’s highly likely they’ll never record anything that feels as good as 1969, no matter how much cash or time they throw at the problem.

A slightly muffled recording or not, there are lots of reasons to dive into these four glorious sides of black wax. The listener gets to enjoy ‘Sweet Jane’ exactly as it was meant to be heard, fresh out of the oven. Reed claimed it was written just hours before that night’s show. When it was released, the album was the only chance Velvet Underground fans had been offered to hear ‘We’re Gonna Have A Real Good Time Together’, ‘Over You’ and ‘Sweet Bonnie Brown/ It’s Just Too Much’; and it proved the first opportunity to hear the band blasting through ‘Lisa Says’ and ‘Ocean’; as radically different versions of these had already turned up on Reed’s debut solo LP by that point.‘But it is primarily ‘What Goes On’ that allows the listener to judge the oft touted line – on a good night this band were ten times better live than they were on record – to be actually free of hyperbole.

It was hard for the Velvets to ascend to this level and by rights, they should have gotten there sooner. Warhol dug repetition. The windows of a skyscraper. Soup cans. Remorseless nights out in NYC. Slight tonal differences. Slight colour variations. But the picture remains, largely, the same. Andy’s house band were supposed to be another iteration of this desire – mechanically reproduced noise art – but it wasn’t until some of the craziness he and his retinue themselves generated (and the group’s own bona fide wild-eyed artist, Cale) fell out of the picture that the VU really hit their locked, minimalist, hypnotising groove.

‘What Goes On’ as a song is one of the crowning achievements of rock & roll, a positive line drawn under the 1960s that no one noticed at the time, a could-have-been counterweight to all of that Altamont/Cielo Drive, end-of-an-era horror and the only real argument for The Velvet Underground being a great, rather than good, album. But the studio version is merely a sketch for glories yet to be revealed. Even if you skip Lou Reed’s egomaniacal, “Look at me mummy!” ‘Closet Mix’ and pick the restored original mix which eventually surfaced on the CD release, it’s clear that you’re not hearing the best version. There’s something hamstrung about Morrison’s rhythm guitar (due mainly to the suffocating depth he’s been dropped into the mix), something pusillanimous about Yule following Reed in simple chord pattern lockstep, trying desperately not to upstage his new best friend. In 1968 Reed essentially groomed the callow Yule until he started walking, talking and dressing like the frontman. But a few months on the road created a new, if temporary, democracy. The real foundation of this glorious track at the Matrix is Moe’s implacable, metronomic beat, around which Morrisson, chucks and chops, palm muting, dampening, switching between different patterns, creating intense and driving counter rhythms, a throbbing chassis over which Reed stalks magisterially and Yule’s now unrestrained organ playing challenges the listener with the alacrity of a demi-urge. And boy, those markers on the highway just fly by, here’s the next town. And the next. And the next. This is driving music in excelsis. “Good evening. We’re your local Velvet Underground…”

I’ll admit that the one thing the studio version has that the others don’t is the pulse-quickening “mosquito” guitar solo, which Doug Yule likened, not unreasonably, to hearing bagpipes. This reverberant sound was created by Reed laying down three solos. Initially this was just so Yule could choose the best of the bunch but when they were multi-tracked, Reed’s ‘loose’ style suddenly allowed febrile dissonances to phase in and out of perception, like the dying flares of the lysergic experience. Do you dream of being Dr Frankenstein and combining elements of different versions of songs? I do, and if I had the power once I was done adding Keith Richards’ guitar solo to the far superior Merry Clayton version of ‘Gimme Shelter’, I’d get straight on to adding Reed’s studio-recorded guitar break to the 1969 version of ‘What Goes On’.

But other than that it’s perfect.

The Velvet Underground, Polydor

One of the reasons the Matrix material is so good is the length of time the band spent getting used to the club, gauging how the PA responded at full tilt, mentally mapping the shape of the room, learning to tweak their process little by little as they began pulling in ever bigger audiences. For all of their druggy rep there was an immense amount of discipline to be found in their camp. Two long sets a day, no two sets the same and when it came to the songs, massive, if not infinite variety. They realised immediately that the space they were working in would not support any attempt to overwhelm the audience, so they had to try a different tack to win them over instead. So their sets remained relatively restrained, their berserk climactic freak outs, caught on such ragged but brilliant boots as The Legendary Guitar Amp Tapes, were deferred indefinitely at that venue. Morrison would remain unhappy that people tended to judge the idea of the Velvets as a live entity purely on the basis of the Matrix recordings as their MO in bigger venues was wildly different. And he was right, on a lot of these other, scrappier recordings they sound like a different band. There’s a version of ‘Sister Ray’ recorded at Boston Tea Party in 1969 where they genuinely sound like they’re morphing into Pussy Galore in one section, then EyeHateGod and then blown out Japanese amp destroyers Mainliner after that. It’s a truly incredible recording – arguably their finest moment. Certainly their pinnacle, when looked at through a certain prism. This is one of the heaviest rock recordings of all time, so if anyone wants to criticise the Matrix material in terms of it being relatively light, then it’s a fair cop. If it’s just the sonic assault and brain fracturing heavy psychedelia you’re after, you won’t find it here. These recordings show something different happening: the band, reacting to the limited properties of a physical space and the audio equipment it contains in the course of attending to a commercial problem, are caught machine tooling a new type of modern hypnosis inducing rock minimalism that would find an even more restrained European echo over the coming years in the guise of Neu!

Once you’ve caught the bug for VU’s minimal hypno-grooves you’ll want more and more. The obvious place to go directly after 1969 is the self-explanatory Complete Matrix Tapes, which features every song from the four sets played across the two November dates. It’s self-explanatory why the 37-minute-long version of ‘Sister Ray’ wasn’t included on 1969 but it’s a revelation, nonetheless. The band may have felt at home in the club, but they weren’t particularly enamoured of the emergent San Francisco Sound they found themselves an island in the middle of. They occasionally had to share a joint headline slot with The Grateful Dead, who, on one occasion, had a quite groovy and relaxed attitude to when their set should end, meaning Reed and co. ended up with a violently truncated amount of time on stage. The next day when the headline slots were reversed, the Velvets temporarily forgot about the size and shape of the room, ignored the subtle limitations of the PA and ended their support set with a version of ‘Sister Ray’ that lasted for nearly three quarters of an hour and pinned the patrons who managed to stay the distance to the back wall. It was their way of saying, ‘Fuck you. Follow that… if you can.’ If you’re rolling your eyes at the perceived teenage stroppiness of this behaviour though, the Matrix Tapes version of ‘Sister Ray’, caught on a different day is actually a master class in dynamic build, pulsing groove formation and delayed gratification. It’s the mirror image of the studio version, to the extent that Lou Reed doesn’t even turn on his fuzz pedal until well after the ten minute mark, but when he does it’s like a cracked dam bursting. At the 20 minute mark, their minimalist hypno-version takes a turn for the fucked up, as Reed and Tucker conjure the inescapable cop violence of the song, powerful snare hits sounding out like gunshots.

It’s when listening to live recordings of ‘Sister Ray’ that I’m at my closest to believing Reed’s questionable assertion that they were incapable of playing any of their songs the same way twice. The unbelievably simple chord structure and a handful of phrases, provided a platform for exploratory improvisation seemingly without limit. If you want to get a flipbook style grasp of what happened to this tune (and if you’re lucky enough to own a copy, or acquainted with the shadier recesses of the internet) listen to Sweet Sister Ray, a bootleg double album featuring three different takes, recorded between 1968 and 1970. At times you may feel like reminding yourself that you’re actually listening to the same track – but to be honest, the chances are, you probably aren’t. ‘Sweet Sister Ray’ was recorded at the tiny Cleveland cellar club, La Cave in April 1968, and bar some lyrical connections what you’re listening to appears to have mutated so much it has become a completely new entity. There were apparently three of these ‘Sister Ray’ “sequels” floating around in 1968 – including ‘Sister Ray Part 3’, which featured Reed playing the role of a hectoring southern evangelist – but scant audio evidence remains of any of them bar this weird lo-fi boot. ‘Sweet Sister Ray’ is cool enough for the first half of its lengthy duration- it’s a rare enough live audio document of the Velvets featuring Cale on bass and organ after all. (And I’d be the first to admit this feature would probably be redundant if a huge cache of good quality live tapes from this period existed.) Reed does his best arrhythmical, atonal ‘Eight Miles High’-style soloing, something he’d later perfect on blistering live versions of ‘I Can’t Stand It’; and it’s enough to make up for the fidgeting recordist occasionally hitting pause and constantly knocking the microphone. But for anyone staying the distance, around the half an hour mark, actual magic starts happening. Reed starts summoning metallic harmonies, conjuring rhythmic cabinet rattle, conducting feedback and marshalling white noise from his amp. He improvises lines about his teenage experiences with electro-convulsive therapy, while the music puts you squarely in the room. It’s like a wild precognitive audial hallucination of Fushitsusha, Tortoise, Spiritualized and Seefeel. It’s fucking brilliant. It sounds like there are five bored people in the audience. And just before the 40 minute mark, as the song finally starts to become recognisable as ‘Sister Ray’, the bootlegger turns his tape off and that’s that.

In chronological terms The Complete Matrix Tapes is the last great document of The Velvet Underground live. I’ve heard some good live recordings from early the next year but for all intents and purposes – despite how brilliant they’d clearly just become – by 1970 it was all over. And the thing that finished them? The temporary absence of Moe Tucker, who had taken maternity leave. It was the lack of the no-nonsense, heads-down-over-the-skins drumming that warped the group into an entirely different entity. This is to the extent that Loaded isn’t really a Velvet Underground album, it’s a dry run for Lou Reed’s solo career. While Tucker is credited on the sleeve, it’s actually Yule’s kid brother Billy behind the kit. It seems obvious to me now that Maureen Tucker was the true heart and soul of the group. You could take away Nico. You could take away Warhol. You could take away Cale. You could wear Morrison down entirely until he simply acquiesced to everything Reed demanded, just so he could have a quiet life. You could take away the Factory. You could introduce Yule. You could let Reed’s ego run wild. But remove Tucker and you’re fucked. Hail, hail rock & roll.

From her departure onwards they’re dead in the water as an invigorating dynamic force in rock music, the evidence is all over Live At Max’s Kansas City – a recording only favoured by the terminally tin-eared, fashion over substance, wannabe NYC scenester clueless. You can tell a lot by simply listening to the hipsters at the bar ordering Pernod in the background. Pernod! Just listen to the drums. Listen to all of that clattering metal, all of those cruise ship band fills, the fussy proto-metal bluster, the macho desire to jam the entire frequency spectrum up with ham-fisted banging… just straight up garbage. That graceful, graceful thing, now permanently broken on a wheel.

But nothing will change the fact that for a good part of 1969 they had reached their apex. When you listen back now it is clear during that six month run they had become the greatest rock band in the world.