It is the voice you notice first of all. It has the quality of one speaking beyond the grave, a croak that is authoritative and ravaged in equal measure. It is the voice that creaks out from a dark alley and nests under the skin. It is the voice of a PI trying to catch a final hopeless break, or a radio broadcaster making his last transmission from some strange inter-zone. It is a voice that possesses the listener, absorbs them, never betraying itself through emotion. It is control in its purest form, clinical, paranoid and alien. Hiding here, in plain sight, is a voice from the void.

If the late 20th century counter-culture ever required an analogue to the G-Man, William Burroughs would have been its prime candidate. On one hand he was fiercely out-of-his-time, sharp-suited and hair close-cropped amongst the Beats, punks and hippies. However, Burroughs also possessed an acidic intelligence and method so intense that culture seemed to mutate to his predilections and predictions. No other writer, with perhaps the exception of the French poet Arthur Rimbaud, can claim such significant influence on musician contemporaries. His influence can be felt in the work of Dylan, Bowie, Patti Smith and innumerable others. As Burroughs wearily intones of ‘Last Words Of Hassan I Sabbah’, "What I have to say is everywhere now".

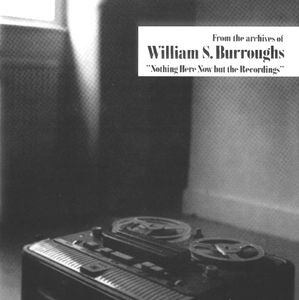

Nothing Here Now But The Recordings was originally compiled by Genesis P-Orridge and ‘Sleazy’ Peter Christopherson of Throbbing Gristle in 1980 from Burroughs’ personal archive, and is re-released by Dais Records. As a collection of Burroughs’ tape experiments, the tracks vary considerably in fidelity and length. Some are bursts of language and noise, shaped by chance operation. Burroughs applied his cut-up techniques as much to audio tape as to the printed page, and the results are the basis of this collection. Tracks like ‘Outside the Pier Prowled like Electric Turtles’ do not make for an easy first listen, being an "occasional muffled report" to use Burroughs’ own words.

The quality of the tapes will deter some, who might favour more coherent compilations such as Dead City Radio. However, it is important to note that Burroughs didn’t see the recordings as art objects in their own right, as Barry Miles elaborates in his biography of the writer El Hombre Invisible, but as experiments. The writer used the tape recorder to explore his obsessions with magical systems and control, believing that the recording itself held potentialities to reveal the latent intentions of the subconscious, or the true voice hidden in the interchange between speaker and machine. Sections warp and stretch, prompted by user interference in the process. It is particularly the obsession with the medium’s ability to exert control that takes precedence here. During Burroughs’ residency in London in the 70s, he used tape recorders to wage a one-man campaign of psychic terrorism against the city’s first espresso bar, Moka. Another useful book for explaining the circumstances and conditions under which many of these recordings were made is the exceptional Beat Hotel, detailing as it does Burroughs’ time at Nine, rue Git-le-Coeur in Paris. It was here that he formed a friendship with Brion Gysin, one of two collaborators in making these recordings, Ian Sommerville – Burroughs’ long-time partner – being the other.

For all the refusals of this work to function as art, the influence of Nothing Here Now But The Recordings is widespread. ‘Last Words Of Hasan I Sabbah’ could be a spoken word interlude from any of the numerous Sun City Girls releases, a sedated Alan Bishop channelling Uncle Jim. Elsewhere lines bubble up and find new life in hip-hop tracks, lodes buried deep under the musical textures to cause unforeseen mutations. Burroughs may not have intended the work for wider release at the point of producing these recordings, but his association with musicians and artists made certain the thinking and methods found grounding elsewhere. It speaks of a personality so strong that it had the power to exert influence even at the point of surrendering its operation to pure chance. Something as simple as the poor quality of the recordings, reported by P-Orridge at the time ("It’s a good job we got them, ’cause they were recorded over twenty years ago and the oxide was actually crumbling off the tapes as we held them."), recalls William Basinski’s divine preservation of audio decay in The Disintegration Loops. It is the voice then that continues: resonating down the alley, nesting under the skin.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/17025-william-s-burroughs-nothing-here-now-but-the-recordings-review” data-width="550">