After the success of bringing back the likes of Os Mutantes, Shuggie Otis and Tim Maia from the depths of oblivion, Luaka Bop – a label that specialises in world music – paid homage this year to another fascinating artist, this time from Nigeria’s funk age. Barely ten years after the Nigerian civil war, which claimed the lives of three million in three years, William Onyeabor built a musical career in his hometown of Enugu, the ephemeral capital of the Republic of Biafra. Between 1977 and 1985, a time of political tumult as his country flitted between attempts at democracy and military regimes, Onyeabor released eight self-produced albums. And then he disappeared.

Four years of work were necessary for Luaka Bop to collate the nine songs of this compilation together. The quest to find Onyeabor was seemingly as difficult as the tracking down of Sixto Rodriguez, as narrated in Searching for Sugar Man, and is documented here, and will be featured in a Luaka Bop documentary slated for an upcoming release. Having completely turned his back on his musical career, it was difficult to secure Onyeabor’s cooperation, and the meeting between Eric Welles, one of two directors of the compilation, and the artist in his "1970s palace" amidst the woods took a long time to make happen. The former Nigerian DJ is wary of discussing his past, and apparently spends most of his days watching evangelist preacher T.B. Joshua on his television.

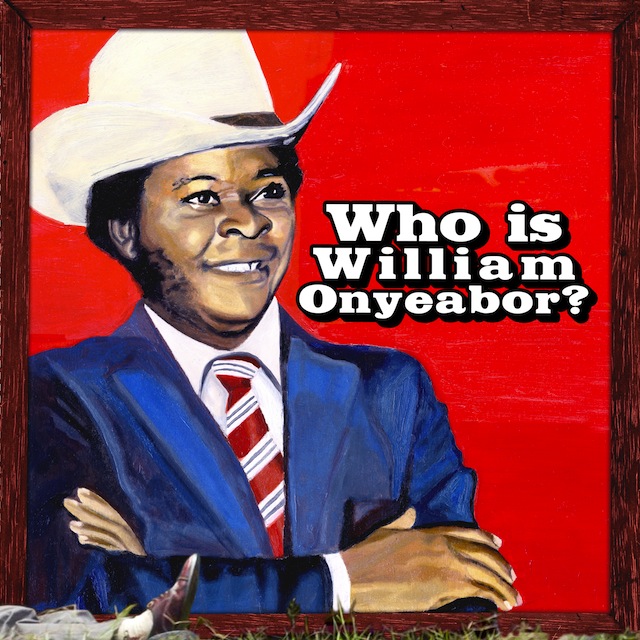

So who is William Onyeabor? On the web he is a myth, promoted only by collectors who exchange rips of his elusive LPs over file-sharing sites, and these days, an original physical album can sell for as much as £600. A few ‘facts’: He is believed to have studied film making in the Soviet Union, before returning to Enugu where he created a production company called Wilfilms and directed a film titled Crashes in Love – “a tragedy of how an African princess rejects the love that money buys.” reads the liner notes. The soundtrack that he made for the film ended up being more successful than the movie, and so he decided to instead dedicate himself to music. Onyeabor went on to release eight albums through his own record label, creating them at his pressing plant and recording studio. Eventually, he left music for Jesus Christ. Today, Onyeabor still lives in Enugu where he is known as High Chief, an accolade given to him by locals for his entrepreneurial success and charity. He owns a flour mill and an internet café. This is the legend of William Onyeabor.

As for the music he turned his back on, it can be summarised as freakishly awesome psychedelic electro-funk, an African counterpart to LCD Soundsystem, a statement made by Luaka Bop themselves. He has been sampled by the likes of Daphni, and his music has been praised by Damon Albarn, Four Tet, and Devendra Banhart, who are planning to resurrect it next spring on stages in Lagos, New York and London. Whether he likes it or not, Onyeabor’s exotic and antiquated music has returned, and will probably hang around for a little while yet.

Who is William Onyeabor? is a surprising – yet camp – African reinterpretation of funk and disco, meant for our bodies and souls, as the album opener ‘Body And Soul’ suggests. While the influence of West African juju music is definitely perceptible, his experimentations with analog synths and drum machines recall Giorgio Moroder’s futurist disco, rather than Parliament Funkadelic. The longer tracks boast multiple variations and peregrinations – not unlike those of Onyeabor’s contemporary, Afrobeat creator Fela Kuti, and reveal a man who certainly spent thousands of hours in his workshop carefully weaving crazy rhythms and sound effects with the several Moog synths that can be seen on the cover of his last album, Anything You Sow.

Beyond the cowboy hat and the dandy clothing that insinuates a notion of a fly guy in Nigeria’s funk age, (cf. the ego trip ‘Fantastic Man’ – perhaps the most thrilling song of the compilation) Onyeabor’s lyrics illustrate the fragile situation of African people in the hands of the Cold War’s wayward princes. Although ‘Atomic Bomb’ transforms nuclear holocaust into a physiological metaphor ("I’m gonna explode like Atomic bomb"), ‘Why Go To War?’ deals with the Nigerian civil war within the global fight between the East and West. The religion that would later become so important to Onyeabor is already present in his lyrics: “Good name is better than silver and gold and no money can buy good name" (‘Good Name’), while on ‘Something You’ll Never Forget’, the female backing singers, who accompany the man in most of his songs, passionately chant a memento mori: "One day you’ll be lying down". Lord only knows what pains made this man give up music…