"Tomorrow, songs / Will flow free again, and new voices / Be born on the carrying stream." -Hamish Henderson ‘Under The Earth I Go’.

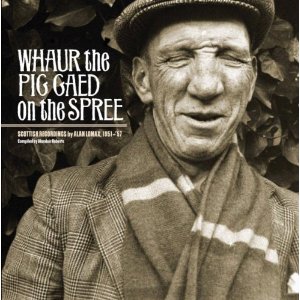

In the summer of 1951 the great American folklorist Alan Lomax made his first song collecting tour of Scotland, humphing his 70 pound Magnecord tape recorder through the north-east and the Western Isles. Having devoted much of his life to recording American folk music, Lomax had turned his attention to music from other parts of the world. Commissioned by Columbia to compile an LP covering the music of the British Isles, Lomax soon realised Scotland deserved an album of its own.

Ewan MacColl introduced Lomax to the Scottish poet and folklorist Hamish Henderson, explaining that the American was "not interested in trained singers or refined versions of folksongs. He wants to record traditional-style singers doing ballads, work songs, poltical satires… bothy songs, street songs, soldier songs, mouth music, the big Gaelic stuff, weavers’ and miners’ songs." Accompanied by Henderson and the brothers Calum and Sorley Maclean (the latter the greatest Gaelic poet of the 20th century) he recorded around 25 hours of material that summer. "The Scots have the finest folk tradition in the British Isles," Lomax wrote, and the songs he found on this and subsequent excursions were "among the noblest folk tunes of Western Europe". Lomax and his companions’ field-work was disseminated through album releases and numerous BBC broadcasts, and played a key role in the development of the folksong revival of the 1950s. In addition to preserving songs and traditions, they brought to prominence such great singers as Jeannie Robertson, Jimmy MacBeath and Davie Stewart.

As an artist whose engagement with tradition has made his own music all the more vital and idiosyncratic, Alasdair Roberts is an excellent choice to curate this sampling of the Lomax archives.

As Roberts writes in the sleevenotes, his recent work has been very much concerned with Scottish tradition. Last year’s Too Long In This Condition was his third album of folksong reinterpretations, and the recent Archive Trails project saw Roberts don a horse’s skull to perform the initiation ritual of the Horseman’s Word cult. He has also drawn on tradition, musically and textually, to create new work. Although he has aimed to be comprehensive, he acknowledges that the selection here reflects his own interest in ballads and narrative songs. Roberts has chosen not to include any of Lomax’s Gaelic recordings, reasoning that the selection of such material should be left to an expert. While it’s a shame that there is no Gaelic mouth music or waulking songs here, it does make for a more cohesive compilation, the bulk of material being from the north-east, in particular its traveller communities.

The folk revival was strongly aligned with left-wing causes, and Lomax and Henderson were both committed socialists, the latter being a student of historian E.P. Thomspon and the first English translator of the Italian Marxist philospher Gramsci’s prison diaries. Tradition bearing and song collecting are of course political acts, and it was by guiding ‘the carrying stream’ of living tradition that the folk revival made its most significant contribution. Roberts has eschewed the topical protest songs of the folk revival – you won’t hear the famous ‘Ding Dong Dollar’, an anti-Polaris nuclear submarine song set to the tune of ‘Ye Cannae Shove Yer Granny Aff A Bus’, here – but there is room for Henderson’s tribute to the hero of Red Clydeside, ‘John MacLean’s March’. Set to a stirring traditional tune, Henderson celebrates not only the man, but the labour and independence movements as a whole, as he sings of working men and women marching through the streets of Glasgow.

As Corey Gibson notes, Henderson did not treat the song as a fixed text, but something that is subject to the process of sharing and reinterpretation. The thrill of observing this process in action can be captured by comparing William Mathieson’s fine acapella version of ‘Binnorrie’, included here, to Roberts’ more elaborate arrangement of its variant ‘The Two Sisters’. That the singers gathered here are virtuosic interpreters of folksong is in no doubt. As Roberts writes, "the passion, rawness, command, depth of understanding… and uniqueness of style" of these performers is exemplary. None is more celebrated than Jeannie Robertson, the Aberdeenshire traveller "discovered" by Henderson in 1953. The authority and beauty of her voice is remarkable, and there is great artistry in her control of dynamics, phrasing and mood. Roberts has astutely chosen two tracks not included on current Robertson compilations, Robert Burns’ ‘The Deadly Wars Are Blast And Blawn’ and The Child Ballad variant ‘Davy Faa’. The latter is particularly stunning, with Robertson bringing dignity and sensuality to the tale of a young woman who leaves her wealthy farmer father to run away with a gypsy lad.

Heralded as ‘the last king of the corn-kisters’ Jimmy McBeath is another of the great traveller singers. ‘Hey Barra Gadgie’ is a song in Romany cant, with McBeath reeling off the arcane lyrics with great wit and skill. In a wonderful moment of audio verite, Lomax can be heard across the room, encouraging McBeath to sing the short piece again. That intimacy and directness is common to all these recordings, and as a result they sound utterly alive. McBeath’s richly accented baritone takes on a more noble and elegiac quality for the soldier’s song ‘McCafferty’, its melody based on an Irish air. His travelling companion, singer and accordianist Davie Stewart, is a master of comic songs, and his ‘McGinty’s Meal and Ale’, from which the compilation’s title is derived, is an uproarious yarn about a pig’s drunken "spree". Stewart’s delivery is glorious, particularly in the pinched tone and mock-operatic vibrato he brings to the "lobby / toddy / body" end-rhymes of the first verse. There’s also great humour in the playground rhyme, ‘My Mother and Your Mother’, performed by Aberdeen schoolchildren. "My mother and your mother were hanging out some clothes / My mother gave your mother a dunt (punch) on the nose / What colour was her blood? R.E.D. spells red!" recite the girls with glee. There’s a mordant thrill in hearing such goriness coming from butter-wouldn’t-melt young tongues.

Other fine singers here include Buckie fishwife Jessie Murray, Aberdeenshire farmer John Strachan, and the remarkable Mary Cosgrove, whose vocals on ‘The Collier Lad’ are as arresting and strange as anything by those avatars of old weird America associated with Lomax or Harry Smith. Then there’s John Steven, whose high, androgynous tenor leads a rousing chorus of ‘The Big Kilmarnock Bonnet’. The instrumental pieces are also more than worthy of attention. Having been obliged to play Scottish fiddle tunes at school, it’s taken me a while to come back round to that music, but Hector McAndrew’s graceful and infectious ‘Dean Briggs / Banks Hornpipe’ effortlessly banishes any memories of frustrating lunchtimes spent practising Jimmy Shand’s ‘Bluebell Polka’. I must admit the latter is a cracking wee tune, and Roberts has done well to rescue Shand from the purgatory of tartan and shortbread kitsch by including one of his duets with fiddler Sidney Chalmers. The pair shred with the dexterity and speed of a Marnie Stern or Mick Barr, bringing a lightness of touch and joyful skipping rhythm that is all their own. Scottish bagpipes are perhaps more of an acquired taste, but in the hands of the then 19-year-old prodigy John Burgess they are quite magnificent, as he weaves skirls and grace notes around the melody and drone.

While there are several fine compilations of material from the Lomax and School of Scottish Studies archives available on specialist labels, Drag City are to be commended for making this music available to a wider audience, and packaging it so handsomely. Henderson commented that the recordings he, Lomax and others made had a revelatory effect on a generation, and to hear music this raw and beautiful sixty years on is still a transcendent experience. That this radical folk-art remains an inspiration to folkies and experimental musicians alike is testament to its greatness.