Thirty-five years or so from now, how do you suppose the cultural historians of the 50s will try and summarise the rock music of today? The correct answer, of course, is no answer: while this is a cute and diverting internal parlour game, it’s almost impossible to make more than a semi-educated guess, and the more you ponder it, the more dispiriting it feels. Legacies aren’t rock & roll, they’re for people tasked to engrave the name of their cricket club’s outgoing captain on a big oak panel.

Even as the nuclear fallout from WWIV sloughs our skin off, though, the inequity of the class system will surely still be with us – and with it, a romantic view of culture which emerges from either poverty or a blue-collar milieu. This is where 2015 throws a spanner in the works: it’s almost a truism now that rock is being bequeathed to the middle class hobbyists. If one comes from an underprivileged background and ends up in a band, it’s despite that background, not because of it. Doesn’t stop the tunes banging hard, but who’s gonna want to read about it?

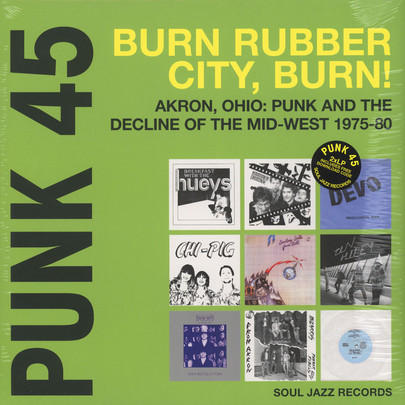

Jon Savage’s liner notes for these two albums leans pretty heavily on the blue-collar backdrop of late-70s Ohio. Extermination Nights In The Sixth City addresses the punk scene of Cleveland, starting with the slashing, formative nihilism of Pere Ubu, Rocket From The Tombs and the Electric Eels and stretching to 1982. Burn, Rubber City, Burn! bundles up bands from neighbouring Akron, of which Devo are by far the best known but in no way the only game in town. Both titles play on the cities’ nicknames, and have a certain bitter irony decades on. Cleveland, the sixth most populous U.S. city at one point, suffered from a prolonged industrial and social downward spiral; Akron’s status as America’s home of tyre manufacturing withered during the 70s, ripping the heart out of the local economy.

But hey! If it wasn’t for other people’s hardship, we’d have missed out on so much great music, right folks? Again, there aren’t easy answers to that, at least not on these compilations. Not many of these bands were explicitly political, and while the myriad releases compiled here (of those which were actually released) didn’t leave anyone minted, that didn’t mean those involved lived a hand to mouth existence. Pere Ubu’s David Thomas, speaking in 1990 and reprinted in Savage’s essay, says, "A lot of people in the band were involved in that urban pioneer thing in the 1970s" – this being more commonly referred to nowadays as gentrification. They’re represented here by ‘Final Solution’ and ‘Heart Of Darkness’, updates on the teenage exasperation of ‘Summertime Blues’ and the fucked-ventricle paranoia of ‘Sister Ray’ respectively. They never tried or wanted to be punk, but by virtue of not being a vacant cover band, Cleveland tagged them thus.

If I – a total outsider to all this, for the avoidance of doubt – were to pick out one band who utterly crystallised the grit of both Cleveland and punk, it would be the Pagans. They existed in their original form for about three years, never recorded an album and made what I truly believe to be some of the greatest punk rock songs ever; that they have more tracks (three) than anyone else on this album gives me hope that Extermination Nights…‘ compiler feels the same way. ‘Street Where Nobody Lives’ is 97 seconds of bassline-driven pep pill thug chug in which Mike Hudson stares bug-eyed into the mystical mirror of self-motivation: "One of these days I’m gonna break out of this place / Then I’ll be on top of this whole fuckin’ human race." ‘I Juvenile’ and the Ramones-ish ‘Dead End America’ aren’t even close to being their choicest cuts, and still sound like the very purest rock impulse. Mike Weldon of The Mirrors (represented here by the oddly pub rock-y ‘Hands In My Pockets’) tells Savage the Pagans were wildly superior to the Dead Boys, who formed in Cleveland and upped sticks to NYC in 1976, and I’m with him all the way.

Some other parts of this compilation have demonstrable sonic connections to other parts still, and some don’t, which is an indicator of a vibrant and creative scene. The Broncs’ sole single, ‘Tele-K-Killing’, is punk that sounds eager to get scrubbed with the powerpop brush. The Defnics arrived after the storm, in 1981, and released a single (‘51%’) on Mike Hudson’s label which injects quasi-metallic muscle into the Pagans’ template. Assuming you like The Dictators, it’s great. The Human Switchboard’s ‘No!’ is all Mysterians-style organ and accusatory Modern Lovers whine. X_X, a band formed by John D Morton after the breakup of the Electric Eels, spin a yarn on ‘Approaching The Minimal With Spray Guns’ which places them firmly and sardonically on the "not" side of the "are we making art or not?" binary.

The lore of the Electric Eels themselves queers the pitch, mind – self-styled "art terrorists" who would go to bars where steelworkers had clocked off, purely to start trouble. (It’s the cosy distance, naturally, that allows us to think of this as anything but wankers acting like wankers.) A brace of Eels rehearsals from 1975 are included here, and whoever mastered them deserves some sort of kudos, as it’s not often that practice tapes have guitar loud enough to open your pores.

To glibly generalise, Akron wasn’t as fierce or as punk-oriented as Cleveland. Its best known 70s output was more commonly pegged as new wave: Devo, as mentioned, plus Jane Aire And The Belvederes, the teenage Rachel Sweet (not included here) and The Waitresses, who went on to quasi-novelty fame with ‘Christmas Wrapping’. The first three of those were picked up by Stiff Records in the U.K., which functioned as more of a foothold in this island’s rock industry than a pathway to success in itself. Stiff also released a scene-snapshot LP, The Akron Compilation, in 1978; if there’s one mild criticism of Burn, Rubber City, Burn!, it’s that nearly half of that record has been replicated here. On the other hand, it’s never been Soul Jazz’s M.O. to pick unheard stuff for mere obscurity’s sake.

Devo’s two numbers both stem from their 1974 demo era, which might plausibly be a licensing issue as much as an effort to showcase their pre-fame, pre-punk prodigy. ‘Mechanical Man’ is slow, creepy and nigh-on hookless minimal electronics; ‘Auto Modown’ is an incomplete-sounding two minutes of factory-rigid Booji blues boogie which is entertainingly easy to imagine being recorded by ZZ Top. It feels vaguely futile to try and contextualize Devo, whose music defies era or geography, but their origins are significant. The band’s Jerry Casale states in the sleevenotes that Devo "was born", conceptually speaking, on the day in 1970 when four of his peers at Ohio’s Kent State University were shot dead by National Guards at an anti-war protest on campus. It’s perhaps remarkable that the response of Casale and his bandmates (most of whom were also at Kent) to state-sanctioned execution manifested itself in sardonic cool-headedness, rather than the kind of slash’n’burn rage that streaked through some of the Cleveland groups.

Akron bands were conspicuous by their sarcasm, or ironic detachment, or slanted social commentary. To the millennial buggers of 2015, these things are usually spoken of pejoratively, yet in the 1970s, rock’s default setting was earnestness. From their name onwards, Rubber City Rebels gruffly reflected the region’s blue-collar vibe. Protopunk clatter ‘Kidnapped’ is the pick of their two songs here, donning a metaphorical ballgown and (I assume) referencing Patty Hearst with stone-hearted glee. "Rich kids got their problems too / Daddy’s money gotta pull you through / I wish I was poor, can’t take it no more!" The other straight-up punker on here, ‘Laugh’ by Hammer Damage, has the finest and most mirth-filled chorus outside of Flipper’s ‘Ha Ha Ha’ and will probably pay your rent for a month if you find an original.

As with Cleveland, media attention and moderate success didn’t seem to spawn stylistic bandwagon-jumpers in Akron: no band here is obviously "post-Devo" or "post-Rubber City Rebels". Tin Huey, who also had Kent State origins, played gawky art-rock with sax and synths; one of their members, Ralph Carney from the group is still making music today, partly in the capacity of Patrick Carney from The Black Keys’ uncle. Jane Aire And The Belvederes’ ‘When I Was Young’ is a peculiarity, lungful near-AOR vocals paired with a cruddily-recorded backing band. The Waitresses’ ‘The Comb’ is a precise bisecting of new wave and hard rock; its refrain, "I like the girls that dance with girls ’cause the boys won’t dance," presages Blur’s ‘Girls And Boys’ by some fifteen years (this is not much more than an historical amusement, granted). With the addition of arch two-girl-one-boy band Chi-Pig, Rachel Sweet and – in the scene’s most formative era, before she skipped town in ‘73 – Chrissie Hynde, the Akron underground made a passable fist of allowing women’s voices to be heard.

Some of the music across these two compilations is timeless, to the extent music really can be. Some of it, like the minimal synth spurts of Akron’s Denis DeFrange, benefits from knowing the landscape into which it was released. To call Extermination Nights In The Sixth City or Burn, Rubber City, Burn! history lessons, or sociological ones, would probably demean the people involved – it’s a snapshot of an era, aimed at listeners who weren’t there, and undoubtedly some folks won’t have got their due. (Certain members of Devo, the Pagans and Rocket From The Tombs are longer alive to speak for themselves.) It is, however, right and proper that this often raging and epochal music is kept in the public consciousness somehow. And if Soul Jazz’s recent ventures into punk’s archives basically update compilation series like Messthetics, Killed By Death and Bloodstains for a more biddable audience, ultimately that’s fine.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/17201-various-extermination-nights-in-the-sixth-city-burn-rubber-city-burn-review” data-width="550">