Iranian pop music from the 70s is known for its sophistication. With lyrics rich in layers and metaphors, experiments in composition, and a balanced yet developed relationship between composers, lyricists, singers, and studios, 1970s pop reached a level of success yet to be matched after half a century. Its songs are still remembered, performed, and sung by many – possibly more than those from any other era.

With the 1979 Revolution and the emigration of many pop musicians and singers, almost all genres of popular music disappeared until the 1990s, when restrictions eased and a new wave of artists gradually emerged in Iran. Between the 1980s and 2000s, Iranian pop was produced mainly in one city: Los Angeles. That’s where most pop musicians had moved after the Revolution. The well-established production system of the 1970s could not rebuild itself abroad, and this had an immediate effect on the music: it became lighter, less sophisticated, more austere, and often reliant solely on simple keyboards and synthesizers.

While the ‘mainstream’ pop within Iran until the 2000s (if not early 2010s) consisted largely of this diasporic music, in its birthplace, Los Angeles, it lived on the margins of international pop culture centred in Hollywood. The music, therefore, had a paradoxical position from birth: it circulated widely within Iran through copied cassettes yet generated little income – despite its depth of reach. Revenue came mainly from performances in small venues, cabarets, concerts for the diaspora, and weddings in Los Angeles itself. Another paradox echoed in its musical history: once having a sophisticated and elitist tone, the same music had to compromise with lower production standards and stature abroad.

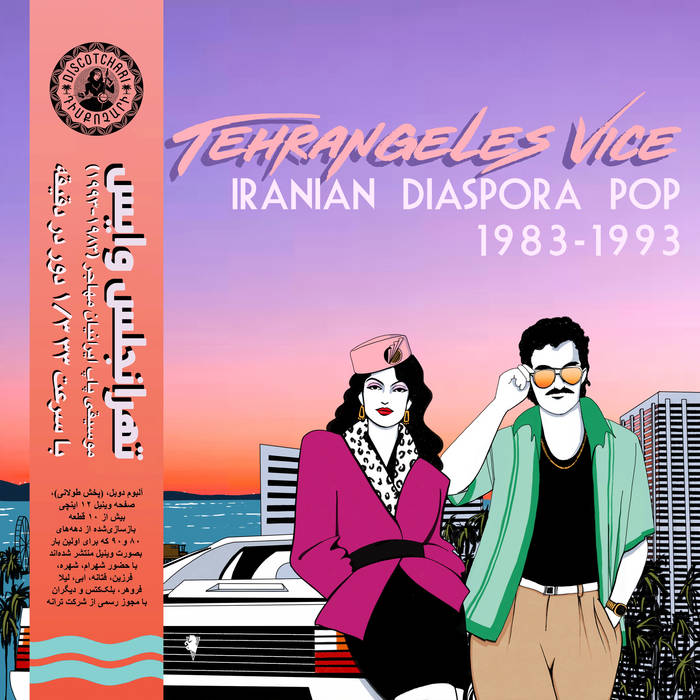

This compilation captures the paradoxical nature of Los Ānjelesi music (as it is called by Iranians): a light-hearted dance music, often associated with vulgarity and low taste (though only recently beginning to be taken seriously), yet with roots in a more refined past. Take the lesser-known first song on this compilation, ‘Man Va Tou’ (“Me and You”) by Shahrokh, as an example of a re-emergence of the 1970s ghost: synthesizers, a dynamic bass line, active strings and electric guitar, a fashionable arrangement, lyrics reminiscent of pre-revolution songs, and a singer entering unexpectedly with syncopation. The opposite example would be the eighth track, ‘Nazanin’ (“Sweetheart”) by Susan Roshan, a singer known for her seductive, trendy style, whose song combines older urban-folk-influenced popular genres with more playful, less ‘artistic’ sensibilities.

Other songs in this compilation move between these poles. Shahram and Shohreh’s ‘Ghesmat’ (1984), for instance, represents a more balanced approach and recalls international hits such as Madonna’s ‘La Isla Bonita’ (1986), as well as ‘Rhythm of Love’ by the Black Cats, a band that, since the 1960s, had symbolised fashionable Western genres such as R&B, rock’n’roll, funk, and reggae.

A questionable aspect of the compilation is the crediting of composers. Before the Revolution, they were often credited equally, if not more than the singers; this compilation, however, maintains a singer-centred approach. Although Manuchehr Cheshmazar appears frequently, major composers such as Sadegh Nojuki, Mohammad Heydari, Siavash Ghomeyshi (who later became a singer as well), and Ahmad Pejman (originally a classical composer) are underrepresented. The selection of singers is also unrepresentative, with notable absences such as Dariush, Aref, Vigen, Hayedeh, and Mahasti, artists who have achieved legendary status among Iranian audiences, incomparable to some of the singers who appear in the album. Some song choices are equally debatable, such as Leila Forouhar’s ‘Hamsafar’ or Ebi’s ‘Kolbeh’, given that both singers have far more commercially successful or musically valuable works.

Tehrangeles Vice is, nevertheless, an unconventional and timely effort that should be understood in light of recent ‘rediscoveries’ of 1980s and 1990s pop nostalgia, both within and outside Iran. Examples include lengthy Radio Javan compilations of 1980s songs popular in Iranian parties since the 2010s, and a series of documentaries on the composers and singers of that era. This trend has begun to recognise Los Ānjelesi music as a distinct movement, with its own history and heritage, compiled, constructed, written, and re-listened to in a characteristically self-reflective way.