The "return to form" is a gigantic critical cliché; most of the time, it signifies wishful thinking and a wilful denial of the empirical evidence that in pop music, genius rarely lasts. When the magic is gone, it’s generally gone for good: cut your losses and get out rather than hanging around parching yourself on a dried-out well of ideas. This has little to do with popularity: it applies equally to acts using empty nostalgia to continue riding high as to those who’ve fallen out of fashion.

In this light, the past decade hasn’t been kind to anyone who’s kept the fire burning for Tori Amos. They themselves have been made punchlines, in much the same way as any fanbase that skews female and/or queer tends to be by the endemically misogynist music press – over-emotional, faerie-obsessed lunatics who seem to remind a surprising number of male journalists of "crazy" girls they dated in college.

When Amos is even mentioned, that same music press has effectively written most of her formidable body of work out of music history, reducing her to the relatively straightforward, categorisable confessionalism of her debut album, Little Earthquakes. But – as Sady Doyle recently argued – she has rarely been given the credit she deserves for the full breadth of her singular discography, whether as an innovator for her still-staggering electronic experiments during the late ’90s, as an influencer on artists from Taylor Swift to Owen Pallett, as a uniquely versatile performer and interpreter in her own right.

Amos hasn’t helped matters herself. Since 2002, the quality of her output has fallen off a cliff: over-long, over-thought albums that creaked beneath the weight of laboriously explained concepts and buried the increasingly rare flashes of inspiration. On some covers, Amos opted to morph into a horrendously Photoshopped bizarre Stepford version of herself – unfortunately, an all too accurate a reflection of the lifeless music within.

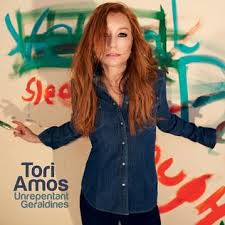

Unrepentant Geraldines is not a "return to form", because ’90s Tori, at the peak of her powers, is never coming back – and nor should she be expected to. Instead, it’s something that’s almost more impressive: Amos has, at the age of 50, found an artistic voice that sounds entirely natural and unforced. In many ways, it’s the direct opposite of the aesthetic with which she made her name – but in the more important respects, it purges almost everything wrong about her latter-day work.

It’s not unrecognisable, of course. Characters and personifications run amok; a penchant for the imagery of Celtic mythology is probably here for good; the piano solo on the title track is a brief moment of time travel to Amos’s younger days. But if Amos’s bewildering opacity, lyrically and otherwise, was formerly one of her most thrilling qualities, it’s startling to hear how much of Unrepentant Geraldines‘ power derives from its directness. Amos tackles her marriage, social patriarchy and her own rebirth – and she does it all head-on. "I hate you – I hate you, I do," she sings to open ‘Wild Way’; her tone is tender and the song ultimately ambivalent, but those unvarnished words illustrate the extent to which being understood has superseded Amos’ former ethos of wrapping herself in wordplay, mythology and inscrutable poetry.

Amos seems more at ease with this than ever before. Unrepentant Geraldines has an irresistible lightness of touch about it: its charms initially seem modest next to the towers of ambition Amos has previously created, but the generosity of melody and sheer prettiness of the sound wins through in the end. Where Amos once dealt in sonic uglification and confrontation – ripping the surface from the girl-and-a-piano template to reveal the raw blood beneath, embarking on wild flights of electronic fancy – Unrepentant Geraldines is the first time since 2002’s sprawling Scarlet’s Walk that Amos has succeeded in making an album that sounds invitingly soft, rather than blandly middle-of-the-road. Its arrangements are full of casually satisfying details: the single ping of a triangle to conclude ‘Trouble’s Lament’s middle eight; the tangles of guitar, piano and woodwind of ‘Wedding Day’. Amos has also rediscovered the arts of both hook-writing and self-editing out of nowhere: this is a remarkably fat-free album. ‘Giant’s Rolling Pin’ is the only real misstep, and then only because Amos’ idea of levity falls flat into wackiness.

But it’s Amos’ vocal delivery that’s a revelation – neither the raging, Galásian force of nature of her youth nor the glassy sheen of her 40s, but clear as a bell, tender but vigorous, with her high notes and backing vocals doing particularly stellar work. She sounds comforting – and it’s appropriate for the maternal qualities of the songwriting. At times these are explicit – the compassion of the closer, ‘Invisible Boy’. On ‘Promise’, it’s literal – a duet with Amos’ teenage daughter Tash in which the two pass the vocal line back and forth in such a way that you can’t tell whether they’re interrupting each other or finishing each others sentences. Against the odds, it’s a beautiful demonstration of real mother-daughter chemistry.

It’s also present when Amos turns her gaze outside her family. "Trouble needs a home, girls," she sings on the southern gothic blues of lead single ‘Trouble’s Lament’; it’s both a nod to troubled girls of the kind Amos was, but also a sly exhortation for the younger generation to cause trouble. Later, the title track explicitly aims its sights at overthrowing a religious, capitalist patriarchy. "Our Father of Corporate Greed, you absolve corporate thieves," sneers Amos; behind her, a choir coos, "This is the day of reckoning," like those troubled, trouble-making girls made manifest. Its chorus – "I’m gonna heal myself from your religion; I’m gonna free myself from your aggression" – mirrors sentiments Amos once used as catharsis; here, they seem more like a call to arms on behalf of those who still need it.

Most crucially to Amos’ revitalisation, though, is her maternal approach to herself. "I’m working my way back to me again," she sings on ‘Oysters’; elsewhere, the elegantly composed ‘Wild Way’ lays out the dilemma of losing youthful rage in the context of Amos’s marriage, but it could as easily apply to her music. For a decade, it’s seemed as though Amos has wrapped herself in concepts and overthought imagery to avoid acknowledging that loss. But the self-awareness and compassion she shows towards herself as well as others on Unrepentant Geraldines has enabled a genuine rebirth.