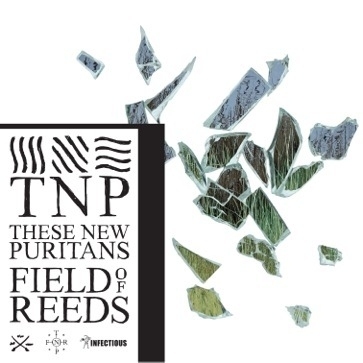

Field Of Reeds. It’s that title that holds the key to These New Puritans’ third album. Fields are terra firma, wilderness tamed, human use of the soil for productivity. Reeds one might more commonly associate with liminal space between water and dry land, murky, misty… they grow in wet beds, not fields, and the juxtaposition of the two suggests to me a place unsettled and undefined, mysterious and strange, like the sets of wavy lines, symbolising reeds, set at different angles on the album’s sleeve. Earth under water, earth replacing water, water reclaiming earth. "You asked if the island would float away," as Jack Barnett sings on the title track, and album’s end.

These New Puritans find themselves out of place and adrift from nearly everything around them as this album emerges to a perplexed public. If ever a contemporary group were a red rag to those who like to bellow "pretension!" before thundering forth, Strokes albums waving, it’s this one. There’s Jack Barnett’s refusal to feel he needs to explain what he does, and the wilful determination to challenge themselves in instrumentation, arrangement and playing. Most of all, though, These New Puritans have defied British indie’s default setting of insipid conservatism, stasis and complacency. Yet their early days as an NME-beloved band, sharing stages with The Wombats and The Twang, and sounding quite a lot like The Fall and various other post-punk luminaries, will have queered their pitch with a snootier section of the public.

Radicalism is relative, and your perception of how far These New Puritans have leapt, and what kind of a leap they’ve made, will no doubt depend on your record collection. But that’s not the kind of value judgement that ought to be made here. Instead, Field Of Reeds should be celebrated for what it is, an exploration of a British hinterland, both geographical and artistic.

This began with their debut Now Pluvial EP in 2006, and continued through 2010’s Hidden, a chaos of gigantic drums against pastoral clarinet (does any instrument better evoke a British vista?), industrial foley recordings and children’s choir, akin to witnessing a storm brew and burst over the the MOD bunkers that lie in ruins on the pebbles of Orford Ness. Field Of Reeds is not a radical departure from that template – there’s quite a similarity, for instance, between the opening of ‘Spiral’ here and Hidden track ‘Time Xone’. On this album, TNPs use similar techniques, tones and instrumentation to create a record that feels more mellow, as if the rough edges of Hidden have been eroded by time and tide.

As was the case in 2010, where much was made in the press of recordings of a melon wrapped in crackers being hit with a hammer to deathly effect, the temptation can be to lose sight of These New Puritans’ ability to create a perfect picture by examining the minutiae of how it was put together. Is it necessary to pick out the hawk, the breaking glass, the Magnetic Resonator Piano?

That’s open to debate. Rather than spending so long examining the map that I miss the view, I personally prefer to approach Field Of Reeds as a vivid, impressionist poem exploring the flat forgotten marsh and mud on the East Coast of England, north, east and west of These New Puritans’ Leigh-On-Sea home. "There is something there… In crashed cars by the train line / there is something there… in between the islands / where we used to swim," Barnett sings in ‘Fragment Two’. This imagery is present in Barnett’s lyricism throughout – he swims to reach "the river’s mouth" in ‘The Light In Your Name’, on ‘V’ "On the island there are no places or people / on the way I’ll find the magic trail in verse". His vocals are confused, obscured, as if you were indeed hearing them across the surface of a body of water at night.

Where does all this come from, this intensity and vision, but also the fact that – and this cannot be overstated – this is a richly melodic and welcoming album? Comparisons are difficult. There’s certainly a Talk Talk comparison to be made here, perhaps in the most pop moments, where intriguingly, there’s even some Enya too. But most of all is an unconscious assuming of Coil’s mantle as musical cartographers of the British unknown. The Coil album Field Of Reeds most conjures in my mind is Musick To Play In The Dark Vol. I – the rolling melody of ‘Organ Eternal’, for instance, shares an energy with ‘Red Birds Will Fly Out Of The East & Destroy Paris In A Night’, while the whole album is a cousin of ‘The Dreamer Is Still Asleep’. These New Puritans have long had a fascination with English magick, devoting their debut album Beat Pyramid to themes of numerology and songs about Elizabethan astrologer John Dee. On ‘Swords Of Truth’, on that album, water becomes figures became self: "I am an island, a mountain, a river… who wrote all the numbers in your body? / I am in the rain, I am in the rain".

Comparisons are also reductive. Instead, what floods out here is the weight of musical knowledge and study that Jack Barnett invests in These New Puritans. He’s not shy, though, in expressing how this is a piece with many actors, even if he might remain dictator (perhaps the main relic of those early Mark E Smithisms). Credit is due here to fellow band members, twin brother drummer George, and bassist Thomas Hein, Portuguese vocalist Elisa Rodrigues, composer Michel Van Der Aa and arrangers Andre De Ridder, Hans Ek and Phillip Sheppard and especially co-producer (with Barnett) Graham Sutton, the former Bark Psychosis man who seems to have been key in helping TNPs achieve their vision.

So Field Of Reeds is built around recurring musical motifs – woodwind, brass, strings, choir, deep bass booms – that seem to blur and dance between tracks. Indeed, this is a record that’s best approached in movements, rather than letting song divisions distract you. As a whole, the structure is superb. The title, closing, track begins like Twin Peaks‘ ‘Laura Palmer’s Theme’ as interpreted by an order of monks – great blasts of bass vocals from Adrian Peacock (he of the lowest voice in Britain) that are pulled out for Barnett’s vocal and piano, before dropping in again with glorious vibration. The booming conclusion is in perfect contrast to the thin, plaintive female voice singing distractedly to itself at the beginning of opener ‘The Way I Do’, and Barnett’s island lyricism comes full circle.

This trick of dislocated time that the music plays on you throughout Field Of Reeds induces reverie, opens up the intangible and the not-quite-there. As Barnett sings, "these are all words lost in dreams". His deliberately obscured vocals combine with tides of sound to create a sense of an unreliable narrator, a confused history. You’re drawn to the opening of Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness where, moored in the estuary, sailors "meditative, and fit for nothing but placid staring" wait for the tide to change. "We looked at the venerable stream not in the vivid flush of a short day that comes and departs for ever, but in the august light of abiding memories. And indeed nothing is easier for a man who has, as the phrase goes, ‘followed the sea’ with reverence and affection, than to evoke the great spirit of the past upon the lower reaches of the Thames."

The estuarine landscape of Field Of Reeds is best seen in two ways: in grand panorama from an aircraft banking over London, when sun glints off the water of the Thames widening toward the North Sea. Or, on the other hand, oozy intimacy along the rough shoreline, traditionally a site for dumping the waste of London. Here, alongside creeks where air bubbles rattle from the mud with the ebbing tide, a rutted horizon offers up gifts of ancient marmalade pots, broken clay pipes, fused and rusted metal. It’s a landscape that refuses, like memory or dreams, to be defined or contained, that forever shifts and opens itself up to new narratives and fresh explorations. These are the images foremost in my mind whenever I listen to Field Of Reeds, a rich, complex album that, similarly, rewards both the grand overview and close attention, and offers up fresh details, insights and emotions with each listen. It succeeds in exploring a British topography in a way that’s both timeless and visionary, delving into the natural, magical, and squidgy unreliability of human memory as they eddy and swirl like the water that surrounds us, and of which we are largely made.